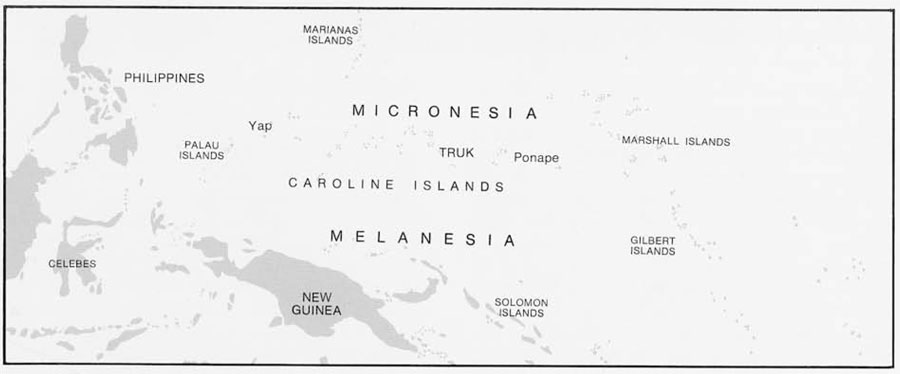

My first field work in the Pacific Islands was for seven months in the great complex atoll of Truk in 1947; and in 1964-65 I spent another ten months there. Truk remained isolated from direct European contact until the 19th century: and it was not until late in that century that any Europeans—a few missionaries and traders—began to take up residence there. Although it was nominally under the tutelage of Spain, no alien government was actually established in Truk until 1903, after Germany bought the Oceanic possessions left to Spain following the Spanish-American War. Japan took possession from Germany in 1914 and held the islands under the League of Nations Mandate until 1945, when they came under the control of the United States. After 1920, Truk experienced considerable immigration from Japan and Okinawa, and many Trukese began to work for cash wages. Although most Trukese continued to grow the bulk of their own food, their cash income allowed them to replace a number of items of traditional manufacture with imported goods of Japanese and Western manufacture.

In 1908-10, when the Hamburg Museum conducted its great ethnological survey of Micronesia, Augustin Kramer and his wife were able to make a splendid collection of Trukese artifacts of all kinds and to prepare an excellent monograph describing local arts and crafts. In 1947, when I went to Truk with a team of anthropologists from Yale University, we were told that if we wanted to learn about traditional crafts we would have to go to the western islands of Paata or Romonum at farthest remove from the administrative and commercial centers in the eastern part of the lagoon. Only there did people still know how to make traditional ceremonial objects; and only there were there women who could still manage the complexities of the traditional loom.

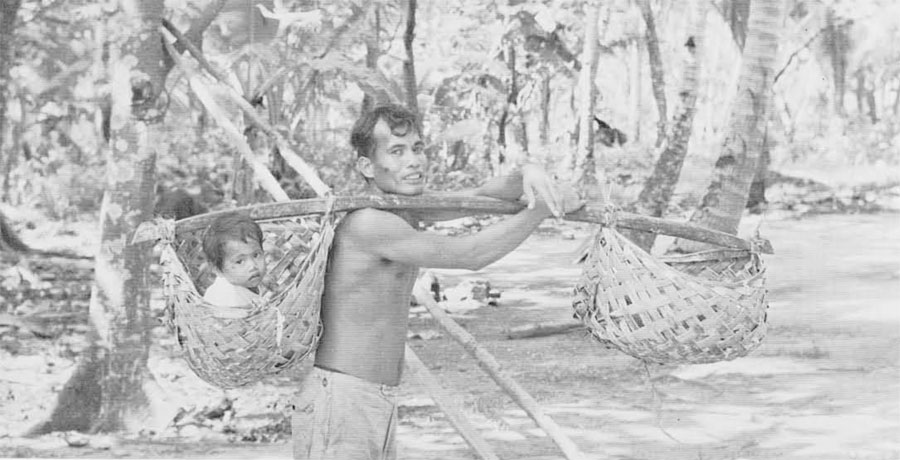

This advice led us to select the small island of Romonum as the locale of our ethnographic work. There we found a number of older people who were skilled in traditional crafts. Frank Le-Bar, a member of our group who specifically concentrated on technology, was able to prepare a comprehensive monograph and to make a study collection for the Peabody Museum at Yale. His collection did not include larger objects, such as canoes, however. Indeed, canoes were not easy to come by. The war had seriously interrupted many normal activities, and the well developed system of commercial fishing and motorized transportation among the islands under the Japanese had reduced the demand for outrigger canoes. A revival of canoe manufacture followed the war, as the people came to understand that the Americans were not going to maintain the level of commercial activity and public services that had prevailed under the Japanese before the war. Paddle canoes of traditional manufacture were still in wide use in 1964-65, especially on the western side of the lagoon. Boats suitable for outboard motors, however, were being built locally for those who could afford the machines to power them. I had no difficulty acquiring for the University Museum a new canoe whose construction was begun just after my arrival. Not only were older men still building them, but young men as well were learning and continuing the art.

Quite different was the situation with other crafts. In 1947, there were three older women on Romonum who knew how to weave. They had not done any weaving for many years, for cotton cloth from Japan had completely replaced the heavier fabrics woven from hibiscus and banana fiber threads. But they had the skill. We commissioned them to weave for us, and several of the younger women took the opportunity to learn weaving from their older relatives on this occasion. But in 1964, these older women were dead, and their younger relatives confessed that they had not tried to weave anything since we had left in 1947. They did not know enough to do anything on their own without the help of the older women.

The last man on Romonum with any knowledge of how to carve spirit canoes, which served as shrines for spirits of the dead, died of tuberculosis in 1964. I was able to locate another man on Paata, to whom the dying man on Romonum referred me. Unfortunately the spirit vessel he made me suffered considerable damage in transit to the Museum.

Small wooden bowls continue to have practical use and are still made. The large wooden bowls used to present food to chiefs on ceremonial occasions had been highly valued heirlooms in 1947 and were difficult to obtain. Political changes have reduced the occasions for their use and their symbolic significance. I had no difficulty in acquiring several of these bowls for the University Museum in 1964.

It is clear that in another twenty years, with the possible exception of outrigger canoes, only the more lowly and practical items of traditional manufacture will continue to be produced in the less affluent communities.