College and did graduate work in Semitic

languages at Harvard University and with

Professor Hermann Ranke at the University

of Pennsylvania. He was appointed Curator of

the Department of Ancient Art at The Brooklyn

Museum in 1936, where he has been ever

since with time out for service in the Army oj

the United States from April 1942 to October

1946. Mr. Cooney has frequently been guest

panelist on the University Museum’s television

program, What in the World?

Regarding his work at Brooklyn, Mr.

Cooney writes: “Assignment at Brooklyn was

to develop the Egyptian collection from a

small accumulation of miscellaneous antiquities

into a major collection of Egyptian art.

ln the course of concentrating on the art of

Ancient Egypt (which is my specialty within

the field) one of the chief tasks has been to

purchase on the international market. Some

of the first purchases were costly errors but,

with the spirit of a gambler, turning a loss into

a profit I concentrated on those mistakes and,

ever since. from the knowledge obtained from

physical examination of these mistakes and

others, the detection of fraud, partial deception,

and hidden rehabilitation of dubious

antiquities has been a major duty. An incidental

result of this concentration has been the

development of a laboratory for the examination

and preservation of Egyptian antiquities

for the Department under Anthony Giambalvo,

the Conservator of the Department. The present

exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum is

really a resume of some of this work.”

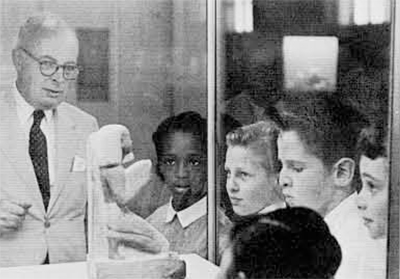

In assembling the exhibition of Egyptian forgeries for The Brooklyn Museum to open in November 1963* as The Forger’s Progress it was necessary to contact many collectors and institutions. It would be instructive though hardly diplomatic to write a series of case histories on the reactions of those approached. The degree of shocked surprise was almost always in inverse ratio to knowledge; those institutions and individuals having minimum knowledge were least likely to co-operate. Invariably they asked, and it is a reasonable question, how is it possible to be certain that an object is a forgery? Clearly, no single answer satisfies all angles of this complex question and, in any case, for these individuals the question was academic if not rhetorical, for it was thrown as defense and not in search of knowledge. No degree of explanation would convince or enlighten them but a study of a few pieces will explain some of the methods by which duplicity in the arts is exposed. The place was Naples and the time about 1850 when the story of our first subject starts. The first personage in the story–though one wonders how many had preceded him unrecorded–was Caleb Lyon, said in an old record in Brooklyn to have been the American consul at Naples, Italy, but I have not been able to confirm this. Apparently he was a cultivated man for he seems to have formed a small collection of antiquities. In doing this he was following a great tradition established by those splendid collectors, the English nobles of the preceding century, whose purchases still feed the art trade of our day. But for Americans, collecting antiquities, even though on a modest scale, was an almost esoteric experience. In the America of the 1850’s there were no art museums (though several historical societies did have art collections) and the very few private collections then in American hands were known, if at all, only locally, and were rarely of consequence. And the Italy of that date must have seemed incredibly romantic and venerable to a representative of the new republic of the West and so have intensified the collecting impulse. What sort of collector Mr. Lyon was or how his collection would be judged today I can’t say, for only one piece from it concerns us here, but that piece suggests he had taste if not knowledge. It is the charming painting in Fig. 1 which was sold to this first owner as a work of art “recovered from a villa at Pompeii.”

Painted in first century style it presents a very romantic lady against a background of rectangles of varied colors. One could not wish for a prettier specimen of ancient painting. Mr. Lyon seems to have been content, possibly even elated, for in 1855 he brought the painting back to this country, retaining possession of it until his death apparently around 1881, for his collections were dispersed at auction early in 1882. From then on we have, and it is a rare case, a detailed record of ownership until the present time. The owners from about 1880 until 1911 when the painting was purchased by The Brooklyn Museum are too numerous to list but several of them demand mention. From Lyon the painting passed to Harrison Plummer, an individual unknown to me but said to be “a painter resident in Boston.” Inevitably he too relinquished ownership of the painting, perhaps at his death, and it was at about this time that it passed into the collection of William H. Strobridge, a man famous in his day as “the blind antiquarian of Brooklyn.” But local fame is fleeting and today even to a Brooklynite the reference is meaningless. Doubtless a little research would reveal him as a person but that remains to be done. It was a picturesque title, one that has always aroused my curiosity for I have wondered how one could be blind and an antiquarian and, above all, how could a blind man appreciate a painting? Very probably the title referred not to his knowledge of ancient objects but to a literary or bookish interest in local history, for this was the common Victorian use of the term. But his possession of the painting remains a mystery. Doubtless in his time “this blind antiquarian” was a distinguished figure but the next owner was even more distinguished. He was a Classical archaeologist on the staff of one of America’s most famous universities. Accompanied by high praise, the painting passed from this scholar to The Brooklyn Museum. If any of these interesting owners ever entertained a doubt about this Roman painting no hint of it has come down to us. Probably the unclad and somewhat winsome charms of the lady diverted objective glances. Even for some thirty years after the painting came to Brooklyn it was blandly accepted. Indeed, when I voiced my doubts to a famous art critic long attached to a leading New York paper he brushed me aside saying, “Absurd, it is one of the finest things in the Museum.” Inexperienced as I then was, I doubt that he was less than sincere for he was hardly subtle enough to be indulging in sarcasm. But despite this high-placed rejection of doubt there is no question that this painting is a work of the early nineteenth century, made perhaps only a decade or two before the American consul purchased it. Indeed, it could be a study for a detain or a painting in the style of an early Ingres or David, for the lady is as completely Directoire in style as one could hope for. The technique seems to be fresco mounted on a terracotta panel, which is odd for a piece of Classical origin. The moral of this story (and to be objective any study of a forgery must be didactic) is that pedigrees are not entirely trustworthy proofs of authenticity. In certain fields, Egyptian art is one of them, proof of existence prior to say A.D. 1900 is adequate evidence against forgery. Even in that field there would be exceptions to this rule of thumb, not that early forgeries are unknown but only that they were invariably so elementary until that date that they are apparent at a glance. Interest in Classical art, however, has existed for so long a time, certainly since the Renaissance, that a pedigree going back a century or more is in itself no reliable guide to age. The warning is apropos today for the contriving of false or legalistic pedigrees has become an important point of the international art trade. The techniques constitute a story of some interest. A detached philosopher might well ask whether this painting is or is not a work of art. And, a more important and provocative point, who was the more fortunate, those early owners who delighted in thinking they had a relic of an ancient culture or the disillusioned curator who knows the object to be a fraud? That is a philosophical point I am not able to settle. And, finances and pride apart, it is hard to determine just why a forgery which has satisfied fails to satisfy when it has been exposed. Someone, and I think it was the philosopher John Dewey, has explained that a forgery fails to satisfy because it lacks those long human associations it had been assumed to have absorbed. That is a romantic point of view and perhaps explains part of the problem, but only part. In contrast to this early interest in Classical art, Americans were very slow to show much concern for Mesopotamian civilization and the culture of ancient Iran. What interest was aroused in this country seems to have been based, as was so much nineteenth century activity in the Ancient Near East, on possible connections with historical facts in the Bible. But there were a few and obscure collectors who made an effort to bring specimens to this country. Among these forgotten collectors were a Mr. and Mrs. Armand De Potter who appear to have been in Egypt and adjacent areas for a few years just before and after 1890. Apparently well-to-do and enthusiastic, they formed an extensive Egyptian collection of perhaps six or seven hundred items–Egyptian antiquities were then abundant–which they brought back to this country. Despite its size the collection contained no outstanding pieces though it did include several interesting items, a few fine bronzes, and a showy coffin and sarcophagus from the famous second find of burials of the priests of Amen at Deir el Bahri. The owners prepared a catalogue, really little more than an elaborate check list, in preparation for showing their newly formed collection at the forthcoming World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893. There it was displayed apparently with some success for I have read that it was awarded a medal, by whom or for what is not clear but we may assume it was for general excellence. After the closing of the Chicago exhibition the owners faced a problem common to all enthusiastic collectors, where to place or store the collection which was not purchased by The Brooklyn Museum until 1908. The catalogue which had been prepared for the Chicago Exposition in 1893 though printed in New York, had been rather pretentiously called The Egyptian Pantheon. Inadequate as it seems today, it must have sold out at the Exposition for a new and more compact catalogue was issued sometime after 1893. It bore neither date nor place of publication and was called The De Potter Collection. Today it is a scarce book, of use only as a record of the collection and as a document in the history of American taste in collecting, but it contains a few illustrations one of which is of some interest in tracing the history of the collection after it left Chicago. A plate opposite page 26 shows the Twenty-first Dynasty coffin and sarcophagus exhibited in a gallery. I had always assumed that the view was taken in chicago, but one day on looking more closely at the dark illustration it suddenly became obvious that the gallery housing the De Potter Collection was the one in the University Museum now used as the Mesopotamian Study Gallery, which leads directly to the very rooms where for many years I studied Ancient Egyptian. Apparently the collection was on loan in the University Museum before it went to Brooklyn and it would now be interesting to know why it did not remain there. Certainly it was no great loss to Philadelphia and a doubtful gain to Brooklyn. But taste and knowledge have advanced since that date. Perhaps the chief interest of the De Potter Collection today, still intact in Brooklyn, is a record of what Egyptian pieces appealed to an American collector at the end of the last century.

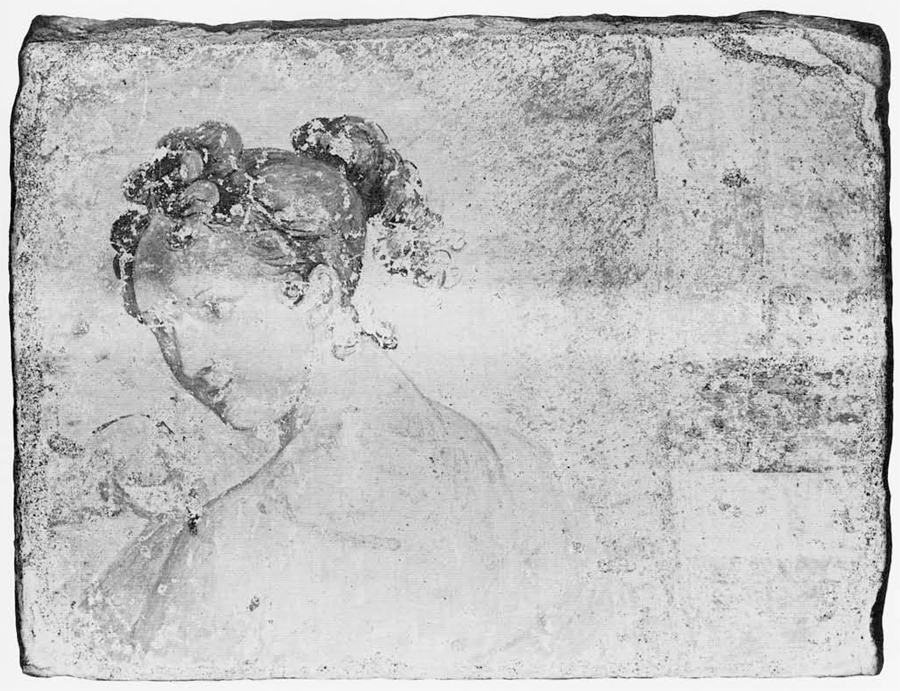

The use of the present Mesopotamian Study Gallery for the De Potter Collection was almost a forecast of things to come, a prediction of the important place the University Museum was to assume in research in the early civilizations of the Middle East. For while this collection was almost exclusively Egyptian, it did contain a few Mesopotamian and Iranian ‘antiquities.’ Some are illustrated in Figs. 2-4 and in the 1890’s they must have appeared very esoteric indeed unless, of course, someone then in Philadelphia was experienced enough to spot them as copies, for copies they are, not to use a harsher word. The relief of Fig. 2 shows a king enthroned and clasping a staff in his right hand, but it would be difficult to identify the man behind the throne were it not that an exact parallel is known in the scene of Darius and Xerxes giving audience, a relief made for the Treasury at Persepolis (see Frankfort, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, PL. 184a). The work is, for its period, rather fine and it is entirely understandable that it could have passed for an antiquity. One mistake made by the forger was the use of alabaster, a stone that points to Egypt as the place of origin, for the Iranian sculptors would certainly have used their fine-grained gray or black limestone.

This limestone was used for the relief in Fig. 3, or at least a light gray limestone was used and then stained to imitate the dark tone of the ancient Iranian medium. The staining has now been removed. This relief too was copied from the ruins of Persepolis, though as it represents an attendant or courtier it is of a type so frequent among the remains that it is made impossible to identify the precise model. Considering the early date of manufacture, the relief is of good workmanship and compares not unfavorably with larger reliefs of contemporary production in Iran. Another relief from the De Potter Collection is shown in Fig. 4. Alabaster was again used but stained to imitate, apparently, the well-known ‘Mosul marble’ so generally used for the great Assyrian reliefs. The composition of this royal scene is pleasing and somewhat unusual with the back view of the guard in front of the throne. Doubtless a basic prototype exists among the surviving reliefs at Persepolis.

As the DePotters purchased these fragments around 1890, they must have been produced not later than the 1880’s and perhaps even somewhat earlier. While several interesting studies on the history of collecting by Americans have appeared, so little has been published on the forgeries included in these collections that it is difficult to be certain, but it may well be that these reliefs were the earliest Iranian fakes to reach this country. Certainly they were not the last of their kind or period to come here, for jumping to this very year 1963 a large and imposing Assyrian relief in limestone, perhaps by the very school that produced the De Potter reliefs, came on the New York market and promptly found a buyer. That episode well illustrates the frustrating fact that however bad a forgery may be there is always someone to authenticate it and, more to the point, someone to buy it. For the pieces so far discussed, style or the lack of it has been the factor revealing forgery. For the specialist style is the commonest and most convincing means of detecting fraud. But, alas, it is the most intangible thing in the world and for the layman, particularly for juries and judges, it is akin to crystal-ball gazing. These solid and unimaginative citizens want, as does indeed the expert himself, solid, tangible proofs of error, and sometimes they are at hand.

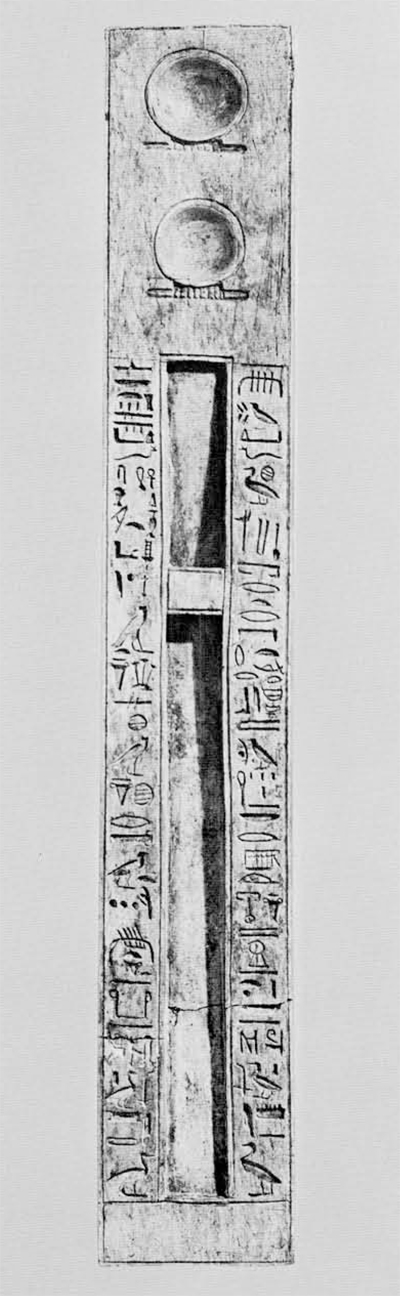

There was for many years in the collection of the famous dealer Joseph Brummer a fine scribe’s palette, Egyptian apparently of the Eighteenth Dynasty (Fig. 5), carved from the steatite and inscribed. It was well made but the inscription was patently wrong, meaningless, and ill-carved. Brummer sincerely believed this pen case to be ancient and explained away the inscription as a later addition or the work of an incompetent scribe. Owners always find arguments to overrule adverse opinions of experienced authorities. Several years later when I again saw the palette a functional error was at once apparent. In the center of this palette, as in all Egyptian palettes, was a depression or well in which the pens were inserted for storage. The well is always in the form of an inclined plane, there is never any variation in its shape or function, but in this strangely inscribed example the well was V-shaped. It had been cut from each end of its length, a completely unfunctional shape as the pens would project and so fall out as soon as the palette was lifted. Even to a layman this was firm proof that the object could not be ancient.

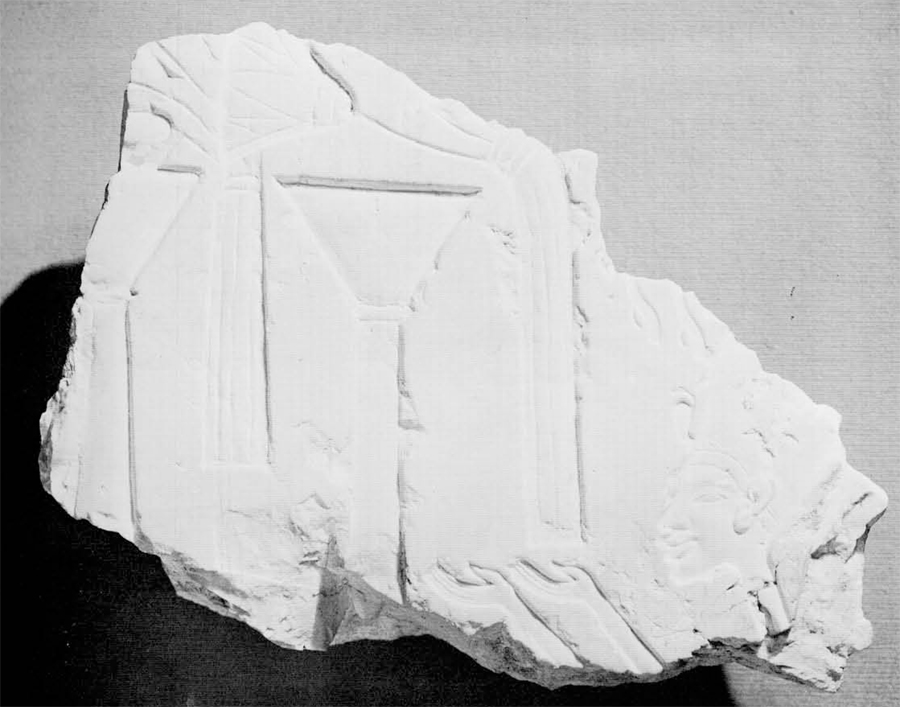

A similar example is shown in Fig. 6 where an error of a sort understandable to anyone has been made. This is a fragment of what was certainly a splendid relief in hard limestone from Tell el Amarna and dating from the late Eighteenth Dynasty. There is no shadow of doubt about the authenticity of this relief but as found it consisted of only the remains of two trumpet-shaped objects. They are conventional offering stands, part of the trappings of royal offering scenes. Despite its fine workmanship, so minor a fragment had no commercial value, but some forger gave it commercial value by inserting the head of Queen Nefertiti at the right.

It is an imaginative rather than a skilled forgery and it might pass but for one major error. The head of the queen has been placed below the level of the offering tables while in an actual offering scene the stands would be at about the waist level of the queen or, in other words, the scale of the head is completely at odds with the basic composition. A comparison with any royal offering scene would illustrate the error at once. In the case of this object the fraud could also be shown by exposing the worked surface to ultra-violet ray. Under this purplish light the ancient areas fluoresce lavender while the recent addition glows a telltale amber. But ultra-violet is not always so obliging. A type of forgery that is often most puzzling to explain is one that was not made originally with any intent to deceive but which has by changed circumstances (and intensified by the owner’s imagination) become a forgery if not in a legal at least in a practical sense. The disconcertingly convincing copies of ancient bronzes long made at Naples with encrustation of ancient appearance are classics of this type.

Catalogues are available showing what is produced and when first sold there is no problem involved, but with time and changes of owners these bronzes take on an identity of antiquity. They are among the most frequent problems brought to museums for solution. In the current exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum there are two pieces illustrating an episode involving a reproduction turned antiquity which will probably become a classic story. It is now almost a decade since the three gold beads in Fig. 7 were brought in to me for purchase through an excellent source and with a good pedigree.

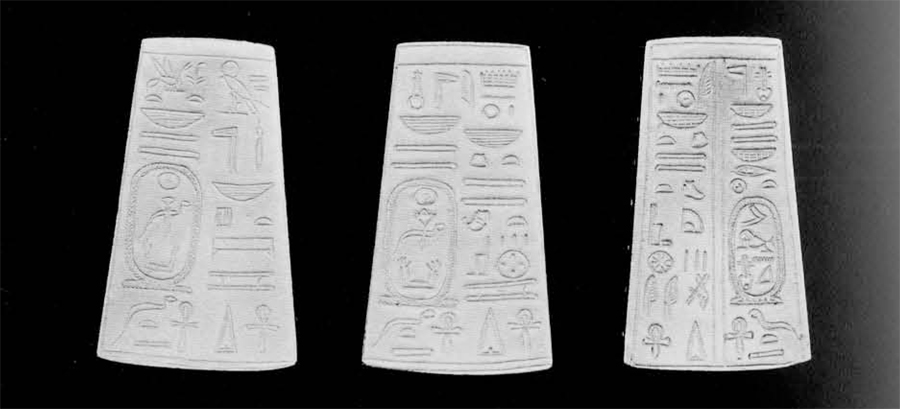

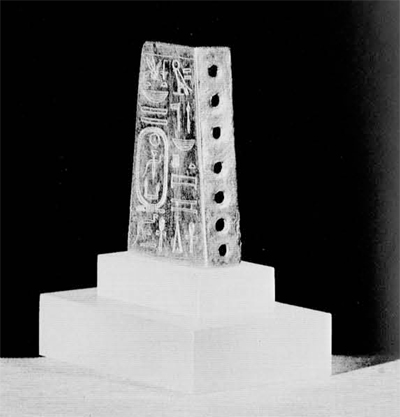

In this illustration the beads seem flat sheets but actually they are trapezoidal in form, inscribed on both faces and pierced seven times on each narrow side. Though called beads their use is far from certain; indeed it is difficult to see how they could have served as beads. Having them brought in was a startling experience for only three of this type are known, and very well known they are, particularly as one of them had for some years been in the Brooklyn collection (Fig. 8). The whole story involves the use of the now frequent flashback. It was early in the present century when the English archaeologist John Garstang was excavating the royal site of Meroe in the Sudan that these three beads first came to light. Seemingly running across a jeweler’s hoard in the ruins of the royal palace, he found the beads in a pottery jar along with glass beads, gold nuggets, and scraps of other objects. The three beads were unique and ever since then nothing like them has been discovered. At the close of the excavation the Antiquities Service at Khartoum retained two of the beads and released the third to the excavator along with other antiquities. Not long afterwards Garstang made a brief report on them, describing them as of pyramidal form but he did not illustrate them or record what had become of the third bead. When the large and important Egyptian collection of the Reverend William MacGregor was sold at Sotheby’s in London in 1922 the gold bead turned up in his collection (fig. 8).

It had apparently been assigned to Mr. MacGregor who was one of the chief subscribers to Garstang’s excavations. At the sale it was bid in by William Randolph Hearst, later passing into other hands. It did not come to Brooklyn until 1949. This digression into recent history explains why the offer of these three beads in 1954 was trying to our credulity. As gold is an easily forged medium, detailed examinations were made of the three beads and the presumed original in Brooklyn. In this case it was possible to prove on technical grounds that the piece already in Brooklyn was ancient but it was hard to explain the source or history of the three new arrivals. In tracing the beads to their recent English owner he swore, quite correctly as it turned out, that they had long been in his family and had come from Garstang. With this lead, thin though it was, and some luck the mystery was eventually solved. Several times in his excavation report Garstang mentioned (as above) finding gold nuggets and gold dust. It seemed strange that he made no mention of the disposal of this precious substance. But what happened was at the end of the excavation when the division of finds was made, all gold discovered was divided equally between the Antiquities Service and the excavator. The Service turned its share of gold in to the National Bank at Khartoum for a credit as gold however ancient has no particular value to a museum, but Garstang was much more imaginative in using his share. How much gold he received seems uncertain but he took all of it to a local goldsmith, instructing him to make exact replicas of the three beads. One wonders at the practical details. Did the goldsmith have to have possession of the originals? The records are silent. A record must exist somewhere of the number and disposition of these copies but I have not been able to trace it. All I can record is that Garstang took these replicas back to England to distribute to his supporters as souvenirs of distant Khartoum. That was half a century ago, and now with the death of the first owners whatever story (if any) went with them has long since been submerged by the tradition that these beads were a gift to grandfather from a famous excavator and so must be very valuable. All of which seems very logical and reasonable. Indeed, the two beads at the left in Fig. 7 have only recently entered the Brooklyn collection and were sold to us as originals at the insistence of the owner who once more explained that they had long been in his family. No one knows how many others still exist in English hands. Life and pocket would be much safer, if less thrilling, for the collector if proper records were always kept of such transactions. But that is asking too much.