Old Souls

One Day I was sitting in the shaded compound of a Beng village in the West African rain forest, playing “This Little Piggy” with the toes of six-month-old Amwe. As the last little piggy went home, I laughed aloud at myself. The baby could not possibly understand the words of the nursery rhyme, all the more because they were in English. To my amazement, Amwe’s mother, my friend Amenan, objected strongly to my remark, which she took as an insult to her daughter. Amenan herself understood not a word of English—although she spoke six languages. Nevertheless, Amenan insisted that Amwe understood my ditty perfectly well. Curious but somewhat skeptical, I asked,“You think so?”Amenan invoked the afterlife. Unlike life in this world, she pointed out, in the Beng afterlife—called wrugbe—all peoples of the world live harmoniously and are fluent in all languages. But how did this result in her infant daughter’s purported ability to understand “This Little Piggy” in English? Patiently, Amenan explained: Babies are reincarnations of ancestors, and they have just come from wrugbe. Having just lived elsewhere, they remember much from that other world—including the many languages spoken by its residents.

How can a baby be accorded full linguistic comprehension when most Westerners see infants as barely on the threshold of any cognitive competence, linguistic or otherwise? To address this question, let us investigate the cultural contours of childhood as it is imagined in one corner of rural West Africa.

Being Born Beng

For the Beng people—a small minority group living in Côte d’Ivoire—the first prerequisite to understanding children and how to raise them is acknowledging that they come from wrugbe. Religious specialists—Masters of the Earth and diviners—emphasize that babies still partly inhabit the afterlife, from which they exit only gradually. Indeed, until the umbilical cord stump falls off, the newborn is still fully in wrugbe—not yet a “person.” If a newborn dies then, the fact is not announced, and no funeral is held.

Once the umbilical stump drops off, the baby starts a difficult spiritual journey out of wrugbe that takes several years to complete. A diviner, Kouakou Ba, explained: At some point, children leave wrugbe for good and decide to stay in this life…. When children can speak their dreams, or understand [a drastic situation, such as] that their mother or father has died, then you know that they have totally come out of wrugbe…. [That happens] by seven years old, for sure! At three years old, they are still in-between: partly in wrugbe and partly in this life. They see what happens in this life, but they do not understand it.

During this betwixt-and-between time of early childhood, the consciousness of the young child is sometimes in wrugbe, sometimes in this life.

Even after children have fully emerged from wrugbe, the afterlife and its inhabitants—the ancestors—remain a palpable presence for the living. For example, every day, before sipping any drink (water, palm wine, beer, soda), adults always spill a few drops on the ground for the ancestors to drink; on other occasions adults make more elaborate offerings. The respect accorded ancestors, and the imagined regular traffics between ancestors and their descendants—on a road traveled regularly by infants and toddlers—serve as the major foundation to the Beng child-rearing agenda for the first years of childhood. Given that infants reportedly lead profoundly spiritual lives—in fact, the younger they are, the more spiritual their existence—specific early childcare practices are expected of a caretaker.

Early Childcare Practices: Leaving Wrugbe

After a baby is born, the child’s grandmothers sit next to the infant and continually apply an herbal mixture night and day to the umbilical stump. This mixture dries out the moist cord fragment and hastens its withering and dropping off, allowing the child to begin leaving the afterlife and becoming a person.

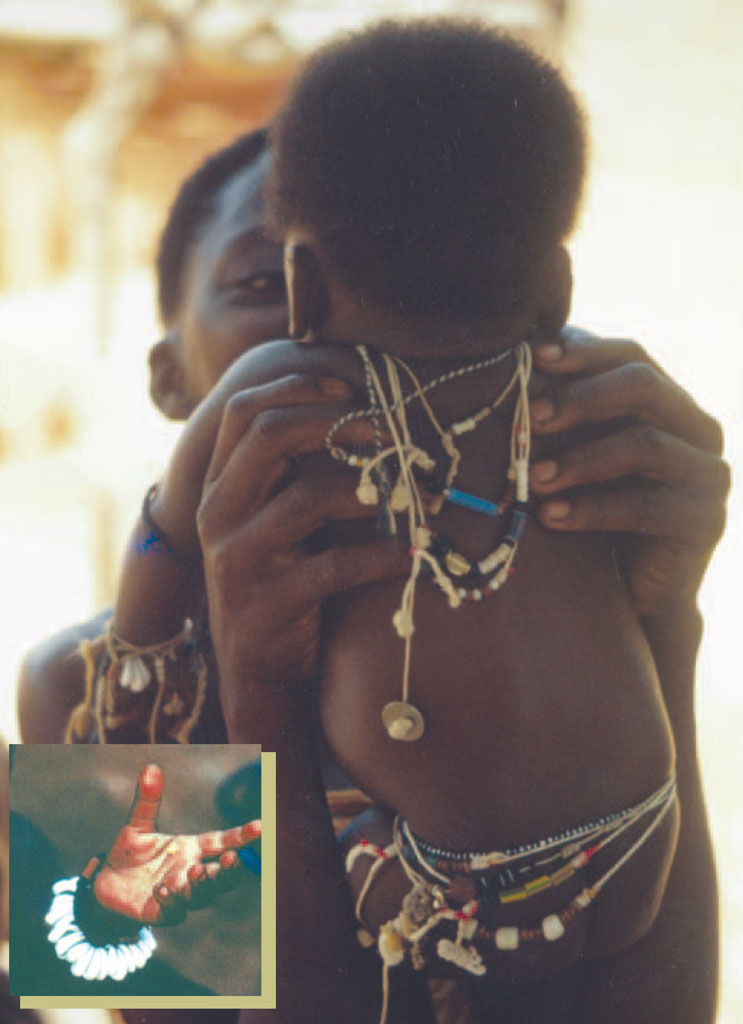

On the momentous day that the stump falls off, the mother and some female relatives conduct two rituals. First, they administer an herbal enema to the baby. From then on, the mother administers an enema every morning and night, effectively beginning “toilet training” the first week of life. A few hours after the first enema, the baby’s maternal grandmother ties a grass necklace around the newborn’s neck to encourage general health and growth; it is worn continually until it eventually tears and falls off. Once this first necklace is applied, the mother or grandmother is permitted to add other items of jewelry. The rituals of applying the first enema and necklace together constitute a pair of early “civilizing” processes inaugurating the baby’s culturally shaped exit from wrugbe and entry into “this life.”

Once they begin to leave wrugbe, infants nevertheless retain powerful memories of that life, and a firm nostalgia for it. In the Beng view, good parents should do all they can to make this life comfortable and attractive, otherwise their child will be tempted to return to the idyllic wrugbe.

Nevertheless, as most parents know, infants are sometimes miserable for no reason. In such cases, the Beng say the baby is probably endeavoring to communicate a longing for something they miss from wrugbe. As the diviner Kouakou Ba explained, when babies cry—or fail to defecate or nurse—they are speaking the language of wrugbe and the bush spirits. However, these means of communication are not understood by parents, who emerged from that other life too long ago to remember its language. Thus parents of an unhappy baby typically take their child to a diviner, who serves as a translator between the living, the ancestors, and bush spirits. The spirits or ancestors first speak with the infant, then translate to the diviner, who then translates to the parents. In this way, through a series of intermediaries, the infant manages to communicate complex desires, rooted in memory, to the parents of this life.

Mothers used to consult a diviner almost immediately after each birth and then regularly during their children’s early years, even if their children were not sick. Almost invariably, the first consultation resulted in the diviner recommending the mother give her newborn a cowry shell. As a then college student named Bertin explained: “All babies must be given a cowry shell as a first gift … because the cowry was important as currency for the ancestors—it was the second most important thing, after gold. The newborn had contact with the ancestors before birth, and the cowry shell reminds the baby of the previous life in wrugbe.”

Another Beng friend added: “Infants like money because they had money when they were living in wrugbe. In coming to this world, they all choose what they want. This could be French coins from the colonial era, or jewelry [usually cowry shells]—what‑ ever is like what they had in wrugbe.” After birth, children retain ties to their wrugbe parents, who continue to look out for their baba. Wrugbe parents are displeased if the child’s parents in this life abuse or neglect their child. If the mother is not breastfeeding or solid-feeding her infant enough, or not taking her sick baby to a diviner or healer, wrugbe parents may snatch the infant back to the afterlife, to await a more responsible couple to emerge as parents. To avoid such a tragedy, Kouakou Ba emphasized, “once the parents of this life discover the baby’s desires, they should do all they can to indulge them.”

Such desires are not always material. Sometimes a diviner may pronounce that a colicky infant is unhappy with his or her name and prefers another one—usually to commemorate her or his wrugbe identity, or a spirit who bestowed the baby on the parents of this life. For example, a baby named Kouassi cried day and night when he was one month old. His mother consulted a diviner, who said that Kouassi was crying because he wanted two bracelets on his left hand, one with cowry shells, the other of silver. Additionally, he had been misnamed: his real name was Anie, after a local sacred pool of water. After hearing the pronouncement, the baby’s mother found the required bracelets, and everyone began calling the baby “Anie.” Reportedly, after this, Anie stopped crying.

The fact that newborns are said to retain powerful memories of the life they just left shapes the way Beng adults conceive of language development. Acknowledging infants’ imputed understanding of language, older people frequently address speech to babies. In hundreds of hours observing babies, I rarely saw five minutes go by when someone was not speaking directly to an (awake) infant.

Kokora Kouassi, a Master of the Earth, explained, “When her baby cries, a mother says, ‘Shush! What’s the matter? I’m sorry!’” On offering her breast, a mother often instructs her infant, “Nurse!” After each breastfeeding session, many mothers question their infants,“Are you full?” A crying baby may be asked,“What’s bothering you?” followed by a series of diagnostic questions: “Are you thirsty? Are you hungry? Do you have a stomach ache? Do you have a fever?” This linguistic attention extends to social encounters. A newborn is introduced to each visitor by being asked,“Who’s this? Do you know?”

Complementing the claim that babies understand all languages, adults teach their infants to speak the Beng language by “speaking for” their infants. In this language-teaching routine, an adult asks a question directly of an infant, and whoever is minding the baby answers for the child in the first person as if she were the infant, in effect, prompting the child with lines that will presumably be repeated months later. For example, a visitor may ask the baby her name. The caretaker holds up the infant and, much as a puppeteer might do, answers as if she were the child: “My name is so-and-so.”

The idea of reincarnation provides a foundation for childcare more generally. Young children learn to feel physically and emotionally comfortable with dozens of relatives and neighbors, many of whom serve as (often impromptu) caretakers. They are held much of the day—but not necessarily by the mother. Babies need to feel constantly cherished by as many people as possible, otherwise they will elect to return to wrugbe.

Beng mothers of infants try to create a reliable network of several potential babysitters who can care for their infants while they work. In addition to offering a practical benefit to the mother, this babysitting network is also meant to make the child feel loved by mangy, helping the infant resist the lure of wrugbe. One way a mother attracts a large pool of babysitters is to make the children as physically attractive as possible. Mothers typically spend an hour every morning and evening grooming their babies, applying herbal medicine in attractive designs, and cleaning the baby’s jewelry to make it sparkle, so as to “seduce” potential babysitters into offering their caretaking services to an irresistibly beautiful baby. A mother may hand her baby to her morning babysitter knowing that the latter is likely to pass the baby to another person if she becomes tired, or the baby fusses, or another person requests the child. Such casual comings and goings are meant to convey to children a feeling of safety, socializing them to feel comfortable with transfers of caretaking responsibility.

Relatives even teach children to feel comfortable with strangers. A “stranger” or “guest”—the Beng call both tining —is immediately incorporated by being made familiar. Before entering a new village, a tining usually contacts a resident to forge a social link ahead of time. The designated host/ess then welcomes the “stranger” into the village, introducing him or her to others as “My stranger.” Eye contact, shaking of hands, the offer of a chair and a drink of water all put a familiar linguistic frame around the unfamiliar. Infants witness such predictable welcoming sessions regularly, which may incline them to interpret encounters with strangers as normal.

Although some Beng infants are classified as gbaneh by their mothers—showing what Westerners would term “stranger anxiety” and accept as normal—Beng mothers maintain that the appearance of any level of “stranger anxiety” is rare.

Beng mothers and others actively socialize their babies to avoid anxiety around strangers so that babies can become persuaded of the friendliness of the world and forget their nostalgia for wrugbe. Most Beng infants seem equally comfortable with their mothers and a variety of others—including strangers. Separating from one’s mother to be given to anyone else is expected to be perceived as a routine event occurring without stress often in a typical baby’s day.

The twinned patterns of welcoming “strangers” and encouraging a broad variety of social ties and emotional attachments accords well with the Beng model of the afterlife. The birth of a baby is not seen as the occasion to receive a strange new creature but rather someone who has already been here before and is now returning as a reincarnated ancestor. The ideology of reincarnation provides a template for welcoming the young “stranger” as a friendly guest with social ties to the immunity. The perceived temptation for the baby to “return” to wrugbe must be constantly combated by those who care for the child. The more people embrace an infant—both literally and emotionally—the more welcome to this world the infant will be. Encouraging high levels of sociability is, in effect, one means by which the Beng combat high levels of infant morality.

The sociability of babies extends to their time asleep. Beng parents expect their infants neither to sleep alone nor to sleep in a horizontal, stationary position nor to take a small number of regularly timed naps every day. Instead, it is important for babies to sleep somewhere they feel welcome and secure. During the day, that usually means being attached to someone’s (usually moving) back or curled up in someone’s lap; only rarely does it mean lying flat on a bed, alone. At night, babies do sleep in a horizontal and stationary position, but they are nestled at least into their mother’s warm body and often into an older sibling on the other side. Unlike in the normative Euro-American context, the goal is to promote interdependence rather than independence.

Again, wrugbe is relevant. Since infants are considered to be partly living in the spirit world, it seems appropriate that they should propose their own agendas and determine their own activities—including their own sleep schedules. In the Beng view, it would be an act of hubris for adults to shape babies’ basic biological timetables when children clearly bring their own (variable) spirit-based agendas to this life.

For the 875 total hours of daytime naps that my assistant and I documented, virtually two-thirds of the observed nap time was spent sleeping joined to someone (whether vertically on a back, or curled up on a lap). Moreover, almost 90% of the slumbering babies were sleeping outside (either on mats on the ground or attached to people’s backs or laps), where they were allowed to feel part of the comings and goings of the village. Only slightly more than 10% of napping babies were sleeping inside a quiet house isolated from social life.

The Culture of Breastfeeding

In Beng villages, the lesson of welcoming sociality even includes breastfeeding. Nursing mothers are urged by older women to breastfeed their babies frequently—the younger the baba, the more often the feeding. As soon as a newborn cries, any nearby woman urges the new mother, especially a first-time mother, to breastfeed, even if the child has just nursed.

During one hour-long observation period with Akwe Afwe and her two-week-old, I counted that the newborn breastfed ten times—an average of once every six minutes. This nursing frequency was typical of other periods I spent with awake newborns. After their first month or so, most (healthy) infants tend to cry less frequented, hence their mothers breastfeed less frequently. Nevertheless, the “nurse on demand” principle remains relevant to older babies. In a sample of 93 nursing sessions observed for 24 babies between three and twenty-four months old, the average frequency of nursing was once every 35 minutes, with no significant differences between younger and older babies in this group. This frequent breastfeeding practice accords well with the Beng model of reincarnation. If babies miss the life they left behind, breastfeeding is a persuasive means of showing infants how pleasurable this life is, how there is plenty both nutritionally and emotionally to comfort them in their moments of sadness and nostalgia.

Just as the baby largely decides when to nurse, a baby may also decide not to nurse. In Bengland, such a child is interpreted as announcing a desire. The worried mother generally visits a diviner to discover what her young son or daughter wishes to communicate. The specialist listens to the wrugbe spirits in touch with the baba, then informs the mother of the baby’s frustrations and gives her instructions on how best to accommodate the child’s desires. For example, as a newborn, Baa’s daughter went a few days without nursing. The family consulted a diviner, who pronounced that the baby was failing to nurse because no one was addressing her by her rightful name. She had been sent to this world by a particular spirit named Busu and wished to be called by that name. The family began calling her “Busu,” and she started nursing immediately.

Among the Beng, a biological mother is only one of many potential breastfeeders. A casual attitude toward wet nursing means that many Beng babies experience the breast as a site not just of nourishment but also of sociability.

During the first day or two of life, another nursing mother is typically a newborn’s first breastfeeder, since a new mother’s colostrum is not seen as nourishing. Once her milk comes in, a mother breastfeeds her newborn very frequently, and around the clock. This can well leave the new mother exhausted. To provide her some rest, other nearby or visiting nursing mothers may casually pick up the newborn to nurse. Wet nursing may also be a temporary measure. If an infant is left with a young babysitter and the baby starts crying, any nearby woman may offer her breast as comfort. If she is not a nursing mother, such a woman serves as a human pacifier.

In short, for many Beng infants, any woman’s breast—even one that has no milk in it—is potentially a site for pleasurable sucking (if not nourishment). This must lead babies to create the image of a relatively large pool of people to satisfy two of life’s earliest and strongest desires—the desire to satisfy hunger (by ingesting breastmilk) and to relieve stress and provide comfort (by sucking). Ironically, for some Beng babies, learning that a large number of people can provide comfort and love begins—literally—at the breast.

Beng vs. Euro-American Models of Child-Rearing

The Beng model of childhood differs drastically from the dominant Western model, and it produces a significantly different child-rearing agenda. Cultural anthropologists have long promoted the notion that daily practices assumed “natural” by one group may be surprisingly absent elsewhere. Moreover, such practices, seemingly “unnatural” to outsiders, make sense when viewed in the context of local systems of cultural logic. Some time ago, anthropologist Clifford Geertz suggested that what passes as “common sense” may be anything but common. Instead, it is a deeply culturally constructed artifice that is so convincingly structured as to appear transparent and self-evident. Child-rearing practices may constitute such a Geertzian artifice, shaped deeply—though often invisibly—by cultural forces.

Should we sleep with the baby or put the baby to sleep in a crib in a separate room? Should we breastfeed or bottlefeed, and when should we wean? It is hard to argue for the existence of a universal system of “common sense” answers to such questions when one cultural system argues strongly for one answer while another cultural system argues for a very different answer. Cultural values speak actively to the choices we make. If we allow ourselves to shed our culturally based assumptions and open ourselves to different models, an anthropological approach to early child development can yield revelatory discoveries. As North American parents pore over the 2,000-plus parenting books now available in bookstores, it is helpful to remember that in other cultural settings, such books would offer very different advice.

Alma Gottlieb is a Professor of Anthropology at the Diversity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She received her B.A. in anthropology and French from Sarah Lawrence College and her M.A. and Ph.D. in cultural anthropology from the Diversity of Virginia. She has also taught classes and workshops at Virginia Dion University, Virginia Commonwealth Diversity, Catholic Diversity of Leuven, Lewis and Clark College, and elsewhere. Her research interests include early child-rearing practices in West Africa and the USA. She has published six books, including A World of Babies: Imagined Childcare Guides for Seven Societies (edited with Judy DeLoache), Parallel Worlds: An Anthropologist and a Writer Encounter Africa (with Philip Graham), and The Afterlife Is Where We Come From: The Culture of Infancy in West Africa from which the material discussed in this article is drawn.

For Further Reading

DeLoache, Judy, and Alma Gottlieb, eds. A World of Babies: Imagined Childcare Guides for Seven Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Geertz, Clifford. “Common Sense as a Cultural System.” In his Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, pp. 73-93. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Gottlieb, Alma. The Afterlife Is Where We Come From: The Culture of Infancy in West Africa. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004.