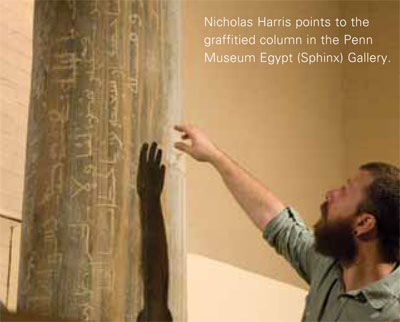

The marble columns, majestic in their own right, contain a further curiosity: they are criss-crossed with Arabic and Hebrew graffiti. Column I carries two examples of Hebrew graffiti. One reads: “In the name of the Lord, we will d[o and will prosper].” Below this paraphrase of Gen. 39:23, commonly appearing at the beginning of Hebrew books and contracts, we read the name “David S,” presumably the name of the inscriber. This inscription appears near the top of the column and avoids the Arabic graffiti, set in neat lines down the middle of the column. Thus, this Hebrew graffito must have been inscribed after the Arabic lines, dating it to the 9th century or later.

The marble columns, majestic in their own right, contain a further curiosity: they are criss-crossed with Arabic and Hebrew graffiti. Column I carries two examples of Hebrew graffiti. One reads: “In the name of the Lord, we will d[o and will prosper].” Below this paraphrase of Gen. 39:23, commonly appearing at the beginning of Hebrew books and contracts, we read the name “David S,” presumably the name of the inscriber. This inscription appears near the top of the column and avoids the Arabic graffiti, set in neat lines down the middle of the column. Thus, this Hebrew graffito must have been inscribed after the Arabic lines, dating it to the 9th century or later.

Column I has four distinct Arabic inscriptions. One particularly valuable inscription reads: “[This is] the writing of Ahmad ibn Sa’id ibn al-Khattab al-Bajali, in the spring of the year 190 [= January–March, 806].” The remainder of the graffiti, judging from their script, also date from the 9th or 10th century. Beth Shean throughout the ‘Abbasid period was a popular point for traffic of various kinds to ford the River Jordan, on the route from Syria to Egypt. But the graffiti have another connotation. Column IV carries two Arabic inscriptions; one reads, alluding to Q. 48:2, “O God, forgive Ahmad ibn Jami’ his sins, what came before and what will follow. Amen.”Ahmad’s contrition and the toppled column, however, are linked. The sight of an ancient ruin frequently provided an ‘ ibra in Arabic, a Qur’anic term (e.g. Q. 12:111) meaning a moral or contemplative lesson from history. The medieval traveler could not help but be struck by the grandeur of past civilizations, yet also could not help but notice that God had eventually erased them and sundered their monuments.