“When we plant corn we place seven or eight seeds in each hole. Of course, we don’t need to grow that many plants for ourselves, but one plant is for the mouse and two are for the crow. They need to eat, too, you know, and they like corn just as we do.” –Clifford Balenquah

Later, Mr. Balenquah continued, Masau’u, a dirty, disheveled, nondescript, smelly old man, assembled the people who became the Hopi.

These different groups of people had been wandering around exploring the Fourth World and then came to this area, first the Bear and Badger people and then, one by one, the others. Masauu asked each group what they could contribute. One group brought corn, another cotton, another the knowledge of this ritual or that one, and so on. Masau’u accepted them, assigning them their specific responsibilities to form the whole fabric of Hopi life and ceremony. To ensure that they remained humble and ever-mindful of their onerous role to maintain the cycle of life, he gave them a hard place in which to live.

I use these stories to illustrate the way the Hopi people conceptualize themselves and their relationships with other living creatures (see box on The Hopi Cycle of Life). All forms of the organic world—and the inorganic, also–are interrelated and interdependent, with none having particular hegemony over the other. People, specifically the Hopi, are but one more kind of life, differing from the others as the crow differs from the mouse. Just as each of them has behaviors, characters, and responsibilities particular to their kind, so do the Hopi. The Hopi’s special responsibility is to keep the world in harmony, in other words, to keep the system going, and they do this by performing an elaborate cycle of yearly ceremonies.

The Hopi World

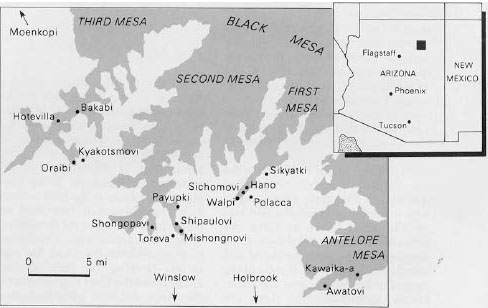

The Hopi live in villages on and at the base of the finger-like projections of the southern edge of Black Mesa in northern Arizona, areas that outsiders now call (going from east to west) First, Second, and Third Mesas (Fig. 1). The villages on the easternmost Antelope Mesa were abandoned early in the 18th century in a convulsive and successful attempt by the Hopi to rid themselves of Spanish missionaries. Continuing to live much as they had for centuries—farming like their Anasazi ancestors of the Four Corners area—the Hopi did not have sustained contact with Europeans until the 1860s, after the Southwest became part of the United States. Their reservation was created by Congress in 1881, an island surrounded by the Navajo Reservation, with borders that have been the source of unfortunate legal disputes estranging the two tribes in recent years.

Masauu gave them a hard land indeed. The mesas are around 6000 feet in elevation, receive an average of eight inches of precipitation a year, and have no permanent water courses. First Mesa is the narrowest and rockiest of all, with no vegetation, only houses, on top. The other two have very sparse vegetation, primarily rabbitbrush and a few piñon and juniper trees. Lone cottonwoods and willows struggle to stay alive along the larger washes. It is a world of stone and sand, hot in the summer and cold in the winter and subject to stinging winds of sand and snow, but it is also a world of serene beauty, dominated overwhelmingly by the brilliant blue sky and its occasional dramatic cloud formations.

Hopi fields look like sand dunes dotted with squat, bushy, widely spaced corn plants. They are located along the base and on the fans of the mesas or out in the flat lands between mesas adjacent to the usually dry washes, small plots seemingly scattered at random. There is, however, nothing haphazard about field placement since the Hopi know from centuries of experience exactly where the roots can tap into underground moisture or where the terrain will carry the occasional rainfalls down the slopes. In very dry years, the people still hand carry water to each individual plant from the few springs on the mesas which provide water for domestic use to fields several miles distant. Drilled wells now provide more water, both for domestic use and for the livestock that graze the uplands of Black Mesa to the north and west.

Although still farmers, the Hopi today derive income from work in the various tribal and government agencies on the reservation, from their famed arts and crafts, and from off-reservation jobs in towns such as Holbrook, Winslow, and Flagstaff. Many families are thus forced to live off the reservation; but rarely do they locate more than a few hours’ drive away, so they can return to their mesa homes and families and ceremonies on the weekends.

The Hopi number around 10,000 people and, like most Native Americans, have a rapidly growing population. There are three older villages on each of the three mesas, plus three more recent settlements at the base of each, and Moenkopi village forty miles west. Although maintaining a degree of autonomy, the villages of each mesa cooperate closely with each other, especially in sponsoring and performing the annual round of ceremonies. Clan membership cross-cuts village and mesa loyalties, while membership in various religious societies adds yet another set of interwoven threads binding the people, especially men, together in this matrilineal and matrilineal society. The ceremonies, in turn, bind the people, the creatures of the natural world, and the spirits of the supernatural world together. To the Hopi, these are a unity, not separable entities.

(4b, right) Crow Mother (Angwushahai-i) Kachina doll. Appearing alone, and considered on the Chief Kachinas, Crow Mother supervises the whipping of the children during the initiation ceremonies in Powamu. She carries a bundle of long yucca leaves, obtaining new ones as needed from her two “sons” the Whipper Kachinas (Hú). After the initiates are flogged, Crow Mother submits to the same treatment, so do each of her “sons.” This doll is also a puchtihu. Usually the crow “wings” are much more exaggerated.

Still, each clan, each village, each mesa has its own set of traditions, variations on central themes perhaps, but the distinctions are important to the people. Thus, the Emergence myth, mercilessly condensed above from Third Mesa resident Cliff Balenquab’s eloquent telling, was recited differently by Terry Honvantewa from Shipaulovi village on Second Mesa. Further, while the Hopi consider all life to be a dynamic state of learning, religious knowledge in particular is acquired by the individual as he or she moves through successive stages of initiation and ceremonial participation. Only the elders of the clan said to “own” a ceremony, and the priests of the religious society which is obliged to perform the ceremony, have full knowledge of the elaborate set of meanings and symbols incorporated in it.

Portions of ceremonies and chunks of their underlying rationales are known to have been lost when catas trophes such as the introduction of infectious diseases by Europeans or prolonged droughts have decimated the population, wiping out whole clans or bringing untimely death to elders before their knowledge was transmitted. However, societies that rely on oral tradition tend to have a healthy flexibility that permits the integration of new elements into a system and the reintegration of old ones into a new consistency. Hopi society is no exception to this process.

Up through the mid-decades of this century, as the Hopi were confronted with adjusting to American schools, a cash economy, and out-migration for jobs, anthropologists and government officials alike were predicting the decline and disappearance of many elements of traditional Hopi culture, especially their religion and ceremonies. In fact, the exact opposite has happened. Ceremonial activities today are more vigorously carried on than they were in the 1950s or 1920s, corn and beans are still planted, and families continue to exhibit that combination of humbleness and humor about their ordained existence and dedication to the Hopi Way that is so much a part of Hopi character. Others may think that love or money make the world go `round, but the Hopi know that is accomplished by their performance of the appointed cycle of ceremonies.

Hopi Ceremonialism

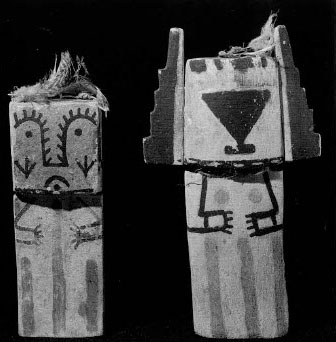

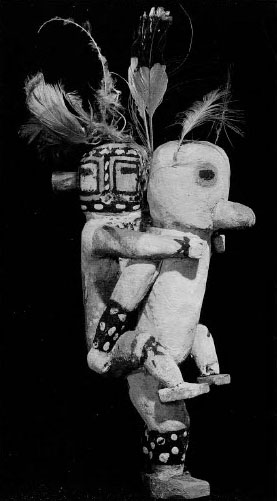

The Hopi have the help of the kachinas, spirit beings, who live with them for seven months of the year. The calendar year begins in late November with Wuwuchim, the new fire ceremony which brings heat back to the earth for germination, and Soyal or Winter Solstice in December which helps keep the sun from leaving the earth and returns it to its summer path (Figs. 3,4a). The first kachinas of the year that visit the villages are usually lone figures of the “Chief Kachinas” personated by men in the masks and costumes distinctive of each. Through January they appear, one by one. The collection of ceremonies known as Powamu, held in February, celebrates their visitation, continues the initiation of the young into the tribe and the Kachina Cult, and heralds new growth with bean sprouts forced into germination in the heated kivas (ceremonial chambers). Many more different kachinas, singly or in groups and varying from village to village and year to year, come during Powamu (Figs. 4b,7,8a).

Like most of the major ceremonies, Powamu takes place over a number of days. There are many ritual events, some performed only by the priests, others by the initiated who personate the kachinas; all involve a complex of symbolic acts and materials invariably including the preparation of prayer feather wands (pahos), altars in the kivas, costumes, songs, and dances that collectively constitute prayers for the blessings of rain and growth of living things. All Hopi children are initiated into the Kachina Cult where they learn that the kachinas are not really the spirits but their fathers, older brothers, and uncles assuming spiritual identities (Fig. 8b,c).

For the next few months, the kachinas dance in one or another of the villages just about every weekend. Until the weather is warm enough in April, the dances are known as Night Dances (Ankwati or Anktioni, Repeat Dances) and take place at night in the kivas crowded with women, children, visiting anthropologists, and privileged friends. With the warmth of spring, they become Plaza Dances, performed outdoors and open to all. Some are Mixed Kachina Dances in which as many as thirty or forty different kachinas dance (Figs. 5,8d). Others are Line Dances in which all dancers personate the same kachina. Lesser ceremonies may be associated with these dances, again varying from village to village and year to year.

Kachina dancers, with very few exceptions, are all men, even those who personate female kachinas. Mostly they supply their own music, their singing muffled by the elaborate canvas or leather masks they wear and accompanied by gourd or turtle shell rattles and bells carried or worn, and sometimes by a drummer. A few dances have a male chorus. The main group dance in a line with simple but stately steps and choreography. “Side dancers,” other kachinas singly or in pairs, may appear with them. Since each kachina has not only a distinctive appearance and voice but also distinctive movements, variations from slow, shuffling dancing to more vigorous and faster tempos occur, depending on the kachinas involved. Generally, a set of four songs/dances (shifting to each of the four directions) constitutes each performance in the plazas.

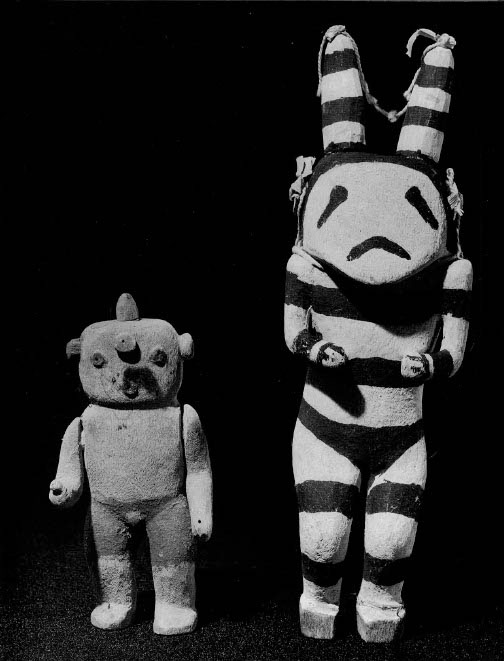

While the dancers, who perform repeatedly, rest between sets, the Clowns appear; also distinctively masked, they both entertain and chastise the audience with burlesques and mimes pertaining to current events in Hopi life (Fig. 6a,b). Their costumes may be added to for these events, to represent everything from bunny rabbits at a dance held on Easter Sunday to blonde-wigged, high-heeled, short-shorted tourists, to some of their favorite protagonists, the Navajo, usually laden with flashy, exaggerated silver and turquoise jewelry and mimed as not knowing how to behave properly (i.e., as a Hopi would). Waves of laughter engulf the audience except for those who have transgressed Hopi codes and whose behavior is being mocked (gluttony, and its implied selfishness, and laziness, especially in regard to ceremonial duties, are sure to be ridiculed).

Dances in the spring and early summer are usually sponsored by a woman and her family seeking special favors or blessings from the kachinas. The dancers are paid with food and presents, and either Clowns or kachinas distribute additional quantities of food and other gifts, standing in the plaza and throwing them to members of the audience amidst much hilarity.

The final major ceremony of the kachinas is the Niman or Home Dance occurring in mid July. Usually only the Hemis Kachinas and their manas (mothers or sisters) appear in this dance now, one of the most beautiful and dignified of all (Fig. 9a,c,d). There is a sadness about it, for at the end the kachinas leave the Hopi, returning to their home on the San Francisco peaks over a hundred miles distant but visible to the southwest of the mesas, and will appear no more in the villages until early winter. Presumably pleased with the many offerings of prayer feathers, corn meal, and ceremonies performed with a “good heart,” the kachinas will send clouds and rain back to mature the crops. One or more eagles, captured as eaglets from nests in the cliffs and tenderly nourished, often for years during which their plumage may be raided several times, will be sacrificed to carry a final prayer for rain to the kachinas as clouds.

At other ceremonies, but especially at this one, uninitiated children are given kachina dolls (tihu) and gifts. Made for children by their male relatives, the dolls are mostly given to little girls so they will learn to identify the different kachinas, while boys are more likely to receive miniature bows and arrows. Not sacred in themselves, or “played” with in the usual sense of the term, the kachina dolls, carved from cottonwood roots, are cherished possessions displayed in the girls’ homes. Married women desiring to have children may also be given dolls.

In August the Snake and Flute ceremonies are performed in alternate years. These are followed in September and October by ceremonies of the women’s religious societies. Dancers in all of ‘these ceremonies are costumed but none are masked since they do not represent kachinas (Fig. 10). The women’s dances, perhaps least well known by outsiders, have an aura of serenity beautiful to behold. Known as Oaqöl, Marau, and Lakon after the names of the religious societies, these ceremonies celebrate the harvest, mark the end of growth, and usher in the frosts and cooling of the earth—until it is awakened again at Wuwuchim and the cycle repeats.

Birds and Feathers

Feathers are an integral part of all Hopi ceremonies. Symbolic of clouds, and therefore rain, tram the association of birds with the sky, they are a part of every costume, altar, and offering made. Collections of prayer wands—sticks or reeds with turkey or eagle down feathers attached by cotton string (also white and fluffy)—mark shrines and sacred spots throughout the villages and surrounding areas. The preparation of these consume many hours of the men’s time before ceremonies begin and as they proceed.

Feathers of one or more birds are attached to virtually all costumes; the kachinas in particular, since they are thought of as cloud spirits, are decorated with feathers. Some, such as Great Horned Owl (Mongwa), Crow (Angwusi), and Crow Mother (Angwushahai-i; Fig. 4b), may use the entire wings of those birds on the masks. “Breath feathers” are the downy eagle feathers at the tips of headdresses and all protuberances on masks; these are repeated in miniature on kachina dolls. Tawa or Sun Kachina has his entire face ringed with eagle tail feathers to represent rays. Crow or raven feathers are used to make thick collar ruffs. On rare occasions, feathers are altered by cutting them into patterns, for example; sometimes they are rubbed with kaolin to enhance the whites, or are dyed red.

The Hopi are estimated to have between 250 and 350 kachinas, representing the spirits of all significant living things in the Hopi world, as well as some physical features. A number of birds are included as kachinas: in addition to those already mentioned, there are Eagle (Kwahu), Canyon Wren (Turposkwa), Hummingbird (Tocha), Mockingbird (Yapa), Screech Owl (Hotsko), Spruce Owl (Salap Mongwa), Prairie Falcon (Kisa), Snipe (Patszro), Roadrunner (Hospoa), Red-tailed Hawk (Palakwayo), Turkey (Koyona), both Hopi and Zuni Duck (Pawik), and probably others. More recently introduced species are represented, too: Peacock or Sun Turkey (Tawa Koyung), Parrot (Kyash), and Chicken (Kowako).

So significant are birds in Hopi rituals that they are among the first kachinas to appear; on First Mesa, according to Fewkes’s observations around the turn of this century, a dance of many kinds of bird kachina personators is one of the earliest performances in the Soyal ceremony, repeated again during Pa-wamu. The Salako (Fig. 9b), symbolic of the sun god and inaugural figure of Soyal, the Winter Solstice ceremony, is a great tall bird whose two-piece beak can be moved by the personator to make clacking noises, and whose “dress” is covered with rows of feathers.

Many Hopi clans signify their identification with birds by taking bird names, as do some of the clans linked together into phratries. Even phratry groupings with other names have birds associated with them. Specific clan legends, accounting for their origins, explain how (and sometimes why) they are related through events in the mythological past.

The harsh environment of Hopi-land, arid with sparse vegetation, does not provide a hospitable habitat for a large and varied avian life. In his field studies in the early 1970s, Bradbury found only 45 permanent resident (winter or summer) species and a few more species—especially waterfowl—that may be migrants through the area. The resident populations are small. Hopi taxonomy, carefully collected by Bradbury, distinguishes most of the species. Feathers from most may be used, but those birds already mentioned as part of the kachina pantheon supply most of the feathers used in costumes and ceremonial paraphernalia.

(8b, 2nd from left) Long-billed or Wupamo Kachina doll. Wupamo appears in Powamu and thereafter in the Repeat Dances; he is surmounted by feathers which may cover the back, has a flat face divided into three panels, and a long, toothed beak with a red leather tongue at the end. He may also serve as a guard, using the yucca whips he carries to ensure participation in community work. He is usually accompanied by a Koyemsi (Fig. 6a) with a lasso to hold him back from his vigorous tendencies or aid him in collecting procrastinators. The static pose of this doll is typical of the carving style of the late 1800s, early 1900s.

(8c, 2nd from right) Marao Kachina doll. This resembles a class of kachinas called Tasap (Tacab) or Navajo Kachinas who appear in Plaza Dances on all the mesas. The projecting visor has a row of eagle feathers and on the top of the head is a tripod structure of red sticks with yarn, red horsehair, and eagle feathers attached. The “ears” are stylized squash blossoms, each with a single eagle feather dangling from the center, and the different colored paneled face and body are typical of this kachina. There is a fan of feathers on the back.

(8d, right) Antelope or Chub Kachina doll. Appearing in the Night and Plaza Dances, game animals are dances as prayers of their increase. They are often offered cornmeal and prayer feathers, for the hope is that Antelope will allow members of his family to be hunted. Unlike the performers of Animal Dances in the Rio Grande pueblos, the Hopi kachinas do not attempt to mimic the movements of the animals when they are danced.

(9b, 2nd from left) Sio Salako or Zuni Salako Kachina doll. The Hopi have two kinds of Salako: Sio, or Zuni, “borrowed” from that Pueblo, and their own Salako Taka with a mana who always appears with him. The Salako Taka and mana appear at Soyal since they are Winter Solstice figures. According to Wright (1973), the Sio Salako is a separate entity, introduced by a Tewa man in 1850, who now appears—if at all—in late spring dances. When personated, he is a towering figure (the entire top of the costume is mounted on a frame carried by the dancer), with a body covered by feathers and draped with shawls.

(9c,d) Hemis and Sio Hemis Kachina dolls. (c, 2nd from right) Hemis Kachina wears a tablet headdress on top of the mask. On the right half of the face are symbols of sprouting squash or gourds, on the left of rain clouds. Hemis wears a ruff or collar of pine boughs, with sprigs of the same inserted in the arm bands, belt, and kilt. (d, right) The Sio Hemis’s flat headdress is topped with semi-circular cloud symbols and has painted designs of sprouting corn, with eagle and turkey tail feathers attached. Today, the Hemis Kachinas with their manas are most frequently the only kachinas appearing in the Niman or Home Dance.

Protected by the Native American Religious Freedom Act, the Hopi may still use the feathers of such endangered species as the golden eagle in their religious ceremonies (see Brown, this issue). For objects made and sold to outsiders, such as kachina dolls, they substitute the feathers of the domesticated chicken and turkey now, or those of birds not covered under the Endangered Species Act. Since few of the native birds have brightly colored feathers, the Hopi buy or trade for parrot and macaw feathers used as topknots on some kachina masks or tied into the hair of other dancers.

Representations of birds and feathers are widely used in Hopi visual art forms. Birds appear in prehistoric rock art, as well as in the remarkable layers of paintings on kiva walls discovered at the site of Awatobi on Antelope Mesa. Both birds and feathers used on the apparent kachina figures are so realistically portrayed that they can be identified by species. In basketry, pottery, and as embroidered decoration on ceremonial textiles, both birds and feathers are highly stylized. The incorporation of birds, bugs, animals, plants, land forms, and other peoples into material objects, in addition to religious belief and ritual performance, is the Hopi Way of demonstrating and perpetuating the life force of our world.