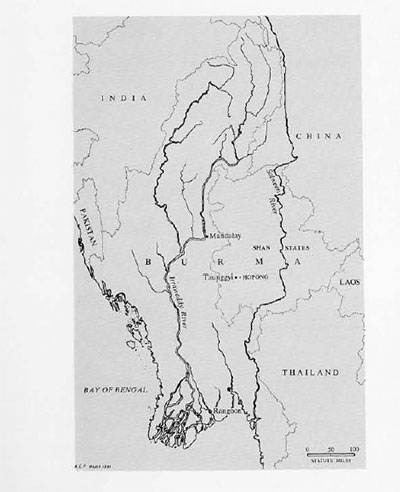

Last spring I spent a few weeks in Hopong, a market town in the Shan States of Burma. The town lies in hilly but unforested country, what I think the English would call rolling downs, and in early May before the monsoon, it is parched and bare, but it has a rugged sort of beauty. A confusion of tribes are scrambled around the Shan States and while the Shans are rarely in the majority, they have usually included the rulers, or at least the rulers have usually called themselves Shans. Hopong, like dozens of other little valley towns around it, was the seat of a Shan Sawbwa, a hereditary chieftain who held dominion over a tiny principality stretching only a few miles in each direction, but whose court was a miniature reflection and imitation of that of the Burmese kings. In a flurry of modernization, the Burmese government has recently bought out most of the Sawbwas’ old powers by granting them a substantial compensation, but the Hopong Sawbwa’s family remains firmly in possession of its Haw, a sort of modest manor house, and the largest dwelling in town.

Most of the people in Hopong itself are Shans, but every fifth day the market attracts hundreds of mountaineers known as Pa-ohs, who walk or ride their ox carts from their villages in the surrounding hills, bringing their produce and carrying home the manufactured goods which even the most remote villager needs for his daily life. In May they sell baskets piled high with garlic and succulent red strawberries, and later in the year they harvest some of the best cigar wrappers in Burma. The Shans of the valleys more often concentrate on their rice paddies, and it is these carefully tilled fields which carpet the flat lands near the town with water and waving green rice stalks, which have permitted enough people to settle near each other so that Hopong could grow into a town. Hopong also has its share of Burmese, and even a few Chinese, Nepalis, and Indians. All these people are still proud to announce their nationality by their dress, and it seems at times as if someone must have deliberately designed the garments to be as different from one another as possible. There are Burmese men in their sarong-like longyis, and Chinese women in cotton print trousers. There are saris, and the enormous colored skirts of the Nepalis, and great baggy pants of the Shan and Pa-oh men. The most bizarre costume is that of the Pa-oh women, who wear black leggings, a black skirt hanging from the waist, a black V-necked smock, and a black jacket, and these four overlapping layers of black are finally topped off by a gaily colored turkish towel wrapped around their heads. Added to these, the many-colored longyis and blouses of the Burmese and Shan ladies, the flowers which women wear in their hair, and the green vegetables, white garlic, and red strawberries displayed by the dealers, make as decorative a market as I have every seen.

As different as their clothing and their languages are, however, all of the people near Hopong, except for the Indians and Nepalis, are Buddhist, and their religion not only offers spiritual satisfaction but unites the varied communities in common festivals which provide much of life’s excitement. The doctrine which the Buddha is presumed to have originally preached might be taken as a somewhat somber one, since it teaches that all existence is suffering, and that the only release from life’s endless round of misery is to reduce one’s cravings and so escape the inevitable pain of disappointment when the cravings are left unsatisfied. In the hands of the gentle people of Southeast Asia, however, Buddhism has become anything but a somber religion, for it is associated with the placid beauty of the pagodas, and with innumerable joyous festivals. A North American finds the manner in which the local people mix secular entertainment and religious observation a peculiar one. Burmese families often picnic at their pagodas, so that within a few feet of people who are praying, throwing libation water and demonstrating their devotion to the teaching of the Buddha, others may be sitting, chatting amiably, smoking and eating, and lacking entirely the appearance of holy worship, except that they glow with the response which the pagodas with their peaceful statues of Buddha and their softly tinkling bells encourage.

Hopong is graced by a magnificent pagoda. It shelters hundreds of statues of the Buddha, some only a few inches tall, others several times as big as life; and like all pagodas in the country it is also embellished with representations of serpents, elephants, peacocks, and several kinds of mythical animals, the most imposting of which are two twenty-foot chinthees, mythical lions, which guard the entrance. The center of the pagoda is a high gilded stupa crowed with its “umbrella,” a golden canopy hung with the bells which ring gently in the breeze.

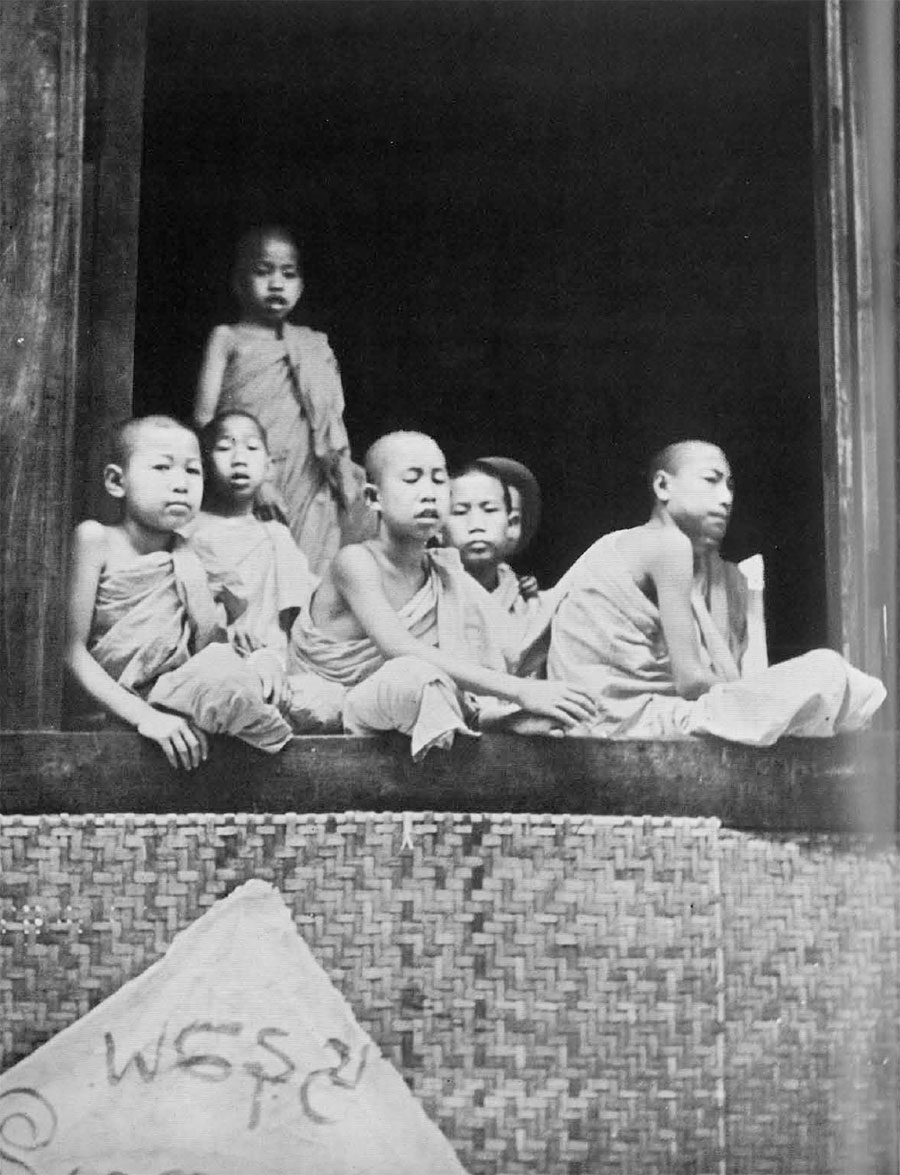

The three thousand people of Hopong also provide enough religious fervor to support three monasteries, each with its compliment of yellow-robed, shaven-headed monks. Every Buddhist male should, at some time in his life, join the holy order. Most men spend only a few weeks in the monastery, for one can leave and even re-enter the Buddhist monkhood at will, but a few, more religiously inclined than most men, remain as monks throughout their lives, studying the Buddhist scriptures, giving instruction to the local youths, and hopefully setting an example of piety for all to follow. Their piety demands celibacy, but according to those who have endured it, a more difficult restriction is one which forbids all monks to eat solid food or take warm drinks after twelve o’clock noon. Every member, whether a monk of thirty years or a novice of a few days, wears an orange-yellow garment, composed of one cloth fastened about the waist with a yellow cord and another draped around the upper part of the body covering the left shoulder but leaving the right one bare. Senior Monks add a third cloth which is folded and laid across one shoulder. In principle the garment is an austere one, designed to promote a simple and untroubled life, and monks must meditate on the principle that it is meant only to cover the body and not to add to the beauty or vanity of the wearer. Like the plain Quaker meeting house, or the plain clothes of the Amish, however, this attempt has failed, for a group of yellow-robed monks is indeed a beautiful sight, walking through a Burmese town under the contrasting blue sky, begging for their food. This they should do every morning, for it provides members of the community with the opportunity to gain merit by giving to the monks, and accumulating merit is vital to the Buddhist whose next existence is dependent upon his past actions.

The headmaster of the local middle school, a young man whom we all addressed by his title–Sayah–invited me to the most elaborate of a series of ceremonies which punctuated my visit. This was a Shunbyu, the ceremony in which boys first put on the yellow robes and become novices, and it turned out to engulf the town to such an extent that I could hardly have escaped it even without an invitation. I was nevertheless glad to be welcomed by one of the community’s leading men, though Sayah, like almost everyone else, was so deeply involved with helping to produce the pageant that I saw him only intermittently. The ceremony re-enacts the time in the life of Guatama Buddha when he renounced the wealth and luxuries which he had known as a prince in a royal family of India, and started his life of wandering and meditation in search of enlightenment. Today, every boy who enters the monkhood first dresses like a prince, and he is treated with every possible honor so that he will have substantial luxuries to renounce when he finally assumes the yellow robe.

The Shinbyu ceremony to which I was invited was performed to initiate sixteen boys. The oldest was fifteen and the youngest only six, but most were between ten and twelve, young perhaps to renounce the world, but the secular schools were due to open within a few weeks, and those who would be returning to their studies would stay in the monastery for only seven days. They were not, moreover, cut off from their families, for if the boys did not actually go to their own houses to beg their mothers would at least send food to the monastery, so even their own parents would have the chance to gain merit by giving to the monks.

Preparations had been under way long before the actual ceremony. Sponsors had been found to support the many activities, and lay committees were appointed to take charge of the clothing of the participants, the decorations for the monastery, and the cooking of food that would be served to several hundred visitors. Sayah’s committee had responsibility for the boys’ welfare, and he was also the special attendant of one of them. From the time their hair is shaved until they finally put on the robes, the boys are subject to spiritual dangers, and it is important that an attendant accompany them wherever they go.

The most resplendent event of all was a procession that wound throughout the town. The boys and hundreds of their relatives, sponsors, and friends gathered in the morning near the monastery which the boys were to join. Whether by good luck or careful planning, it was market day in Hopong so the streets were filled with spectators. The procession was led by a pair of male dancers doing slow weaving Shan dances to the accompaniment of drums. Behind them came a tower of paper and bamboo, carried on the shoulders of four laughing young men and so high that it had to be lowered periodically when electric wires passed overhead. The tower rose in successively smaller squares of colored paper, but above the squares was a “wish tree” constructed of bamboo but looking like a Christmas tree that had lost its needles. People had tied miniature objects onto the tree which symbolized their desires and hopefully encouraged their fulfillment. One woman with several sons had tied a tiny dress to the tree in the hope that her next child might be a girl. Those desiring success in education had attached exercise books, and a few strands of hair were left by those fearing baldness. As a result, the branches of the wish tree were hung with dozens of little items: multi-colored blouses and dresses, miniature pillows, blankets and mosquito nets, mirrors, needles and exercise books, all swaying gracefully as the tower was carried about the town. When the procession was over, the wish tree was set up near the monastery and its tempting objects decorated it throughout the ceremony until the very end when the children of the town fell upon it with shouts of joy, each snatching for himself whatever he could.

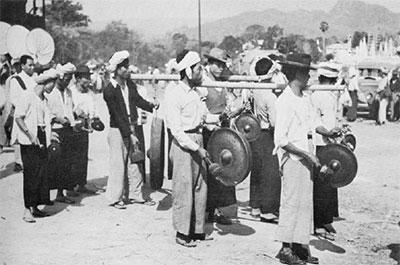

Behind the wish tree came several men beating brass gongs in measured religious beat. I recognized the man who on ordinary days drove his ox cart to my yard with a barrel of water. He was beating the largest gong, a yard in diameter and suspended from a bamboo pole which stretched from his shoulder to that of a partner in front of him. Just far enough to the rear so that the music could be kept distinct, was another musical ensemble, a percussion orchestra riding stylishly in and on an open jeep. One man sat on the hood with a set of small brass gongs, and a xylophone player was mounted on the back seat. Around and between them were several drummers and a flutist, and they played the intense music with a rapid rhythm which is traditional on these occasions. Still another set of musicians beat drums and struck bamboo clappers, keeping time for two youthful dancing girls who did a rapid Burmese dance, more angular that the Shan dance, and much faster and more acrobatic. The girls must have danced for hours that morning, for they were still dancing after the procession was over when many people had gone home to rest. The girls were dressed like boys, but not modern boys. Instead, they wore elaborate silk garments in the tradition of the Burmese royal court–or for that matter, the court of the Shan Sawbwas.

Most of the first half of the procession was not of musicians, however, but was filled with men and women carrying the paraphernalia that the boys would need for their lives in the monastery. This is rigidly prescribed by the rules of the monkhood, and like the yellow robes, is supposed to provide no luxuries, but since it is given to the monks and since the donors gain merit, they sometimes offer objects of a finer quality than the minimum necessary to live. Two parallel columns of women walked by with the bedding that the boys would need, a pillow and blankets for each, together with a parasol and sandals, all rolled up in a bamboo mat and carried securely balanced, one set on each woman’s head. A line of men carried the black begging bowls that the boys would use to collect their food, and the robes themselves, all brand new and some still wrapped in the brown paper of the merchant who had sold them, but a few tied more elegantly, fanned out or rolled up in a spiral. There were bottles of libation water, bouquets of flowers, and large sprays of peacock feathers, each carried reverently by its own group of women. There were cigarets and cigars to be offered to the visitors at the ceremonies. A long train of little girls carried nothing at all, but they decorated the parade with their frilly dresses. One of them also wore a plastic-covered pith helmet, but most were bare-headed.

Toward the back of the procession came the princes themselves riding in state in open jeeps. Ponies have been more traditional for the princes’ ride and occasionally fortunate boys have even been carried to their monkhood on elephants, but when these jeeps were fully decorated they provided a worthy substitute. They were festooned with great loops of artificial flowers, and besides the main attendant each boy was waited upon by two umbrella carriers who walked beside the jeep shading him with tall golden parasols, the color that only royalty was entitled to use in the days of the Burmese kings, when lesser officials had to content themselves with the less exalted color of their own rank. One of the jeeps, a venerable model probably left behind almost fifteen years earlier by the American Army, balked about half the way along. The parade stopped while the carburetor was adjusted and it had to be pushed for a little way, but it eventually arrived back at the monastery in its proper place in line.

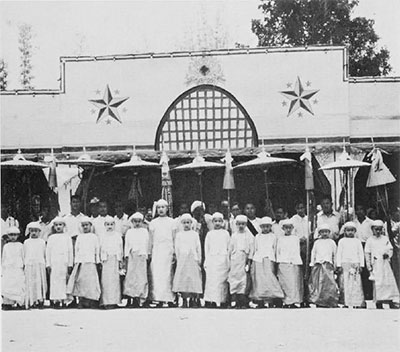

The boys themselves were seated luxuriously two to a jeep on carpets spread over couches mounted behind the driver. They were dressed in silk court longyis and light silk blouses. The parents must usually buy this clothing for their sons though it is sometimes borrowed, and a poor boy may find a man willing to act as a sponsor and see him through the ceremony. Their golden jewelry may be rented for the occasion from shopkeepers. The boys had already had their heads shaved in preparation, but they had tufts of hair tied to their crown and they had been so heavily powdered that their brown skins were lightened to a floury whiteness, and their lips were red with lipstick. The attendants had the duty of renewing their makeup from time to time, and I saw one daintily applying powder from a Max Factor compact. As the parade wound through the town the boys looked comfortable enough. One of the older boys relaxed urbanely on his throne, his eyes shielded with sun glasses and his mouth filled with a cigar, but most sat quietly, a little wide-eyed at becoming the center of so much attention.

The eight jeeps were followed by an equally ancient truck, laden with the final orchestra of the procession, this one featuring a piano and two instruments with necks and strings like a violin but with a metal horn replacing the sounding box. Last of all came the town madman, a vacant look in his eyes, a wad or areca nut and betel leaf in his cheek, and hair streaming uncertainly in most directions. He did a caricature of a Shan dance, his arms waving vaguely out from his sides as he revolved in approximate time to the music from the truck ahead. Nobody paid him much attention, but he followed the parade clear around town and back to the monastery, for the two hours it took to make the circuit.

Beside the monastery, a pandal had been built–a large area shaded with a flat mat roof above and lined with mats below. Along one side of the pandal was a platform upon which the princes were installed. The floor of the pandal was occupied for much of the next two days by groups of visitors who came to see the boys or simply to watch. They squatted on the mats, nibbled at the pickled tea leaves and fried garlic which were distributed about the floor in bowls, and drank endless cups of the clear sugarless tea that the Burmese call “rough” tea, and to which the people of Hopong frequently add a pinch of salt.

In the evening the boys were taken to the pagoda to worship, and then they returned to spend their last night at home. At the pandal, however, a stage had been erected and a variety show was produced for everyone else’s amusement. Like every other part of the festival, the expenses of the show were borne by a public-spirited member of the community. The man who contributed to have the stage built happened to be the proprietor of the local gasoline station. Whether or not his support brought good will to his business, it surely gained him personal merit. The dialogue and songs were in Shan, but a Burmese play was presented the following night, and presumably the black-garbed Pa-oh women who sat on the floor of the pandal smoking cigars, chatting, and occasionally nursing their babies, simply enjoyed the spectacle without understanding the words.

The investiture ceremony itself took place on the day following the procession. Sayah told me that this would begin a little after twelve, but that friends would come to present gifts to the boys before that, so I arrived about eleven and sat in the pandal sipping tea for about an hour while relatives and admirers of the boys brought them gifts of money or of such useful articles as soap and toothpaste. One of the duties of Sayah’s committee was to compare the clothing and ornaments of the boys and harmonize them. That morning a few of the boys arrived from home laden with too many gold ornaments and they had to give up some so that none would outshine the others. The clothes of the boys, which draped about them in unaccustomed splendor and complexity, had to be continually retucked and their pink silk turbans, an elegant version of the towels that other people wear around their heads, were repeatedly retied. At noon the boys were dressed as beautifully as possible with great folds of silk cascading from their waists, and they all lined up outside the pandal for photographs. Afterwards they returned to their platform, however, where they took off their best clothing in preparation for their last meal before entering the order, and their last food for the day. I had not eaten since early in the morning and the steaming piles of white rice and golden curry made me hope that the ceremony would not be too long delayed. I contented myself with rough tea and fried garlic, but the boys took a long time with their rice, and then had to rearrange their clothing once more, so two o’clock passed before any real move was made to start the ceremony. The crowd grew larger as townspeople drifted in, until finally a sudden pre-monsoon rain and wind storm drove everybody into the monastery. As I peered up at the complex tiers of corrugated iron roofs and through scattered rust holes to the glowering sky beyond, I was doubtful if the monastery would be much dryer than the mat-roofed pandal, but it proved possible to move away from under the holes and wait for the storm to pass.

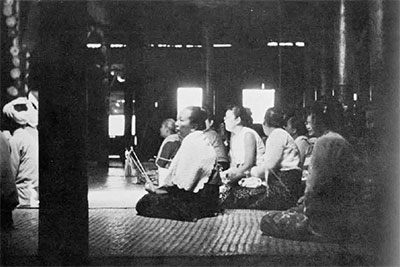

The greatest part of Burmese and Shan monasteries is occupied by a single large hall. At the back is a raised platform with Buddha images, a high throne for a senior monk, and frequently a grandfather clock and other miscellaneous objects of beauty. Space is left for the monks to sit, elevated slightly above the laity who face them from the floor. That afternoon the monks filed on to their platform from one side while the princes sat in a line facing them just in front. Libation water and the more elaborately rolled and folded robes were piled beside them. Each boy was accompanied by his attendant, and I could just see Sayah’s checked silk longyi as he squatted behind his protegee, occasionally whispering instructions of adjusting a bit of clothing. Several hundred men, women, and children filled the room behind and to the sides.

The ceremony could not begin as long as the tin roof resounded with the clatter of the rain, but as soon as the storm quieted the monks began to chat. In the congregation we sat with our legs doubled up respectfully so that our feet would not point toward the monks and the Buddha images on the platform. The congregation murmured a short invocation and then bowed in unison, almost touching their foreheads to the floor. The boys, in their high unchanged voices chanted a formal request to the monks for the right to put on the yellow robe, and the monks intoned their reply, asking if the boys had received the permission of their parents, and if they were prepared to follow the ten precepts which are incumbent upon all Buddhist monks. When the piping voices answered that they and their parents were both willing, a white cord which had been stretched between the line of boys and the line of monks was lifted over the heads of the boys and laid between them and the congregation. The attendants respectfully handed the robes to the monks who carefully unfolded and returned them. The monks changed again. There was more grave bowing and every face showed concentration on the knowledge that all of life is suffering and pain.

And then, at a moment which every one in the congregation but me knew when to expect, the boys raced. They leaped to their feet and snatched at their princely garments. Their attendants grabbed for the robes and swirled them around the boys’ waists and over their shoulders. Cloths of all colors flew about in a turmoil of excitement which stretched the length of the platform. The monks behind them grinned at the exuberance of their new colleagues, and many of us in the audience stood up to get a better view and to give encouraging shouts to the boys and their helpers. One of the youngest boys stood momentarily naked as his own eagerness to get himself undressed outdid the ability of his attendant to drape him discretely from the outside, first. A monk smilingly pointed at one of the boys, and laughter rippled through the audience as they realized that he had managed to drape his unaccustomed clothes incorrectly, and leave the wrong shoulder bare. Another tried to tie the wide upper cloth around his legs, and ended by stumbling about ober the long lower edge. The boys had never tried to tie on the yellow robes before, and though their attendants had worn them at one time, they must have found it confusing to have to clothe another and smaller person, but the first boy finished within five minutes and the last in no more than ten. As each boy finished he knelt down in his place, until sixteen new novices lined the platform, now turned like the older monks to face the congregation.

Again the monks chanted and the congregation bowed, and a relative of each boy sat behind him carefully dripping libation water to announce to the spirits that the order had acquired sixteen new members. Sayah, who had gathered up the princely garments of his protegee and carried them off to a back corner of the hall, came and sat on the floor beside me. He leaned over and whispered in my ear that the first boy to finish dressing would be considered to have the longest period as a member of the order, and so he would have the greatest chance to accumulate merit.