In 1931, the Penn Museum’s Matto Grosso Expedition landed a serendipitous opportunity to court the celebrated Brazilian Army general who had mapped the country and led Teddy Roosevelt through the jungle, by offering him a lift in their state-of-the-art Siko rsky S-38 aircraft. A successful trip meant vital access for the expedition to sustain its work. General Rondon’s first airplane ride would prove to be an adventure in its own right, an odyssey of avoiding hazards in the early days of aviation.

An Impressive Career

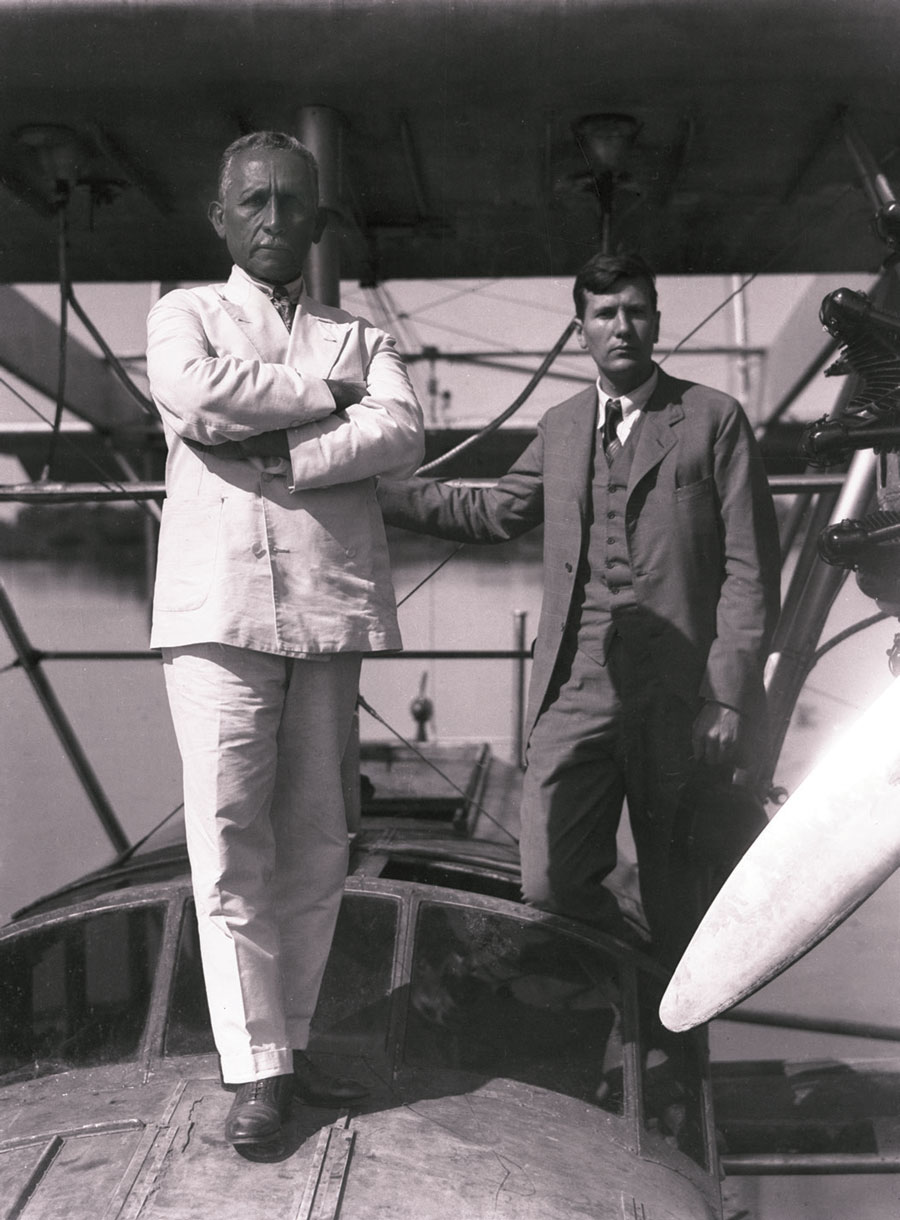

At 5’ 2”, Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon should not have commanded attention, especially alongside 6’ 2” E.R. Fenimore Johnson, the Philadelphian financier of the Penn Museum’s Matto Grosso Expedition—an American group spending 1931 near the Brazil-Bolivia border hunting, collecting indigenous artifacts, and film-ing Big-Cat, an action-adventure “talkie” movie. However, on this overcast June 12 in Corumbá, newspaper photographers, reporters, local dignitaries, and curious townspeople swirled around the 65-year-old Brazilian Army general who was wearing a crisp white, double-breasted linen suit. Rondon’s arrival made news: he was Brazil’s leading citizen, a national hero.

Few people had accomplished more than Rondon, who for 40 years had defined and mapped Brazil’s borders and linked the frontier to coastal cities. From late 1913 to 1914, he led Theodore Roosevelt along the uncharted Rio da Dúvida (River of Doubt) and into the Amazon River basin while the world awaited their return. A humanitarian, Rondon established a federal bureau, Serviço de Proteção ao Indio (SPI), to protect indigenous peoples’ rights. In addition to his scientific and humanitarian activity, Rondon, perceived as incorruptible, was assigned to put down one armed rebellion, passed on a request to lead another, and was detained in the country’s recent coup d’ état. Yet, for someone whose life defined “action” and “adventure,” Rondon had never flown, even though manned flight began 27 years earlier.

The General and the Matto Grosso Expedition

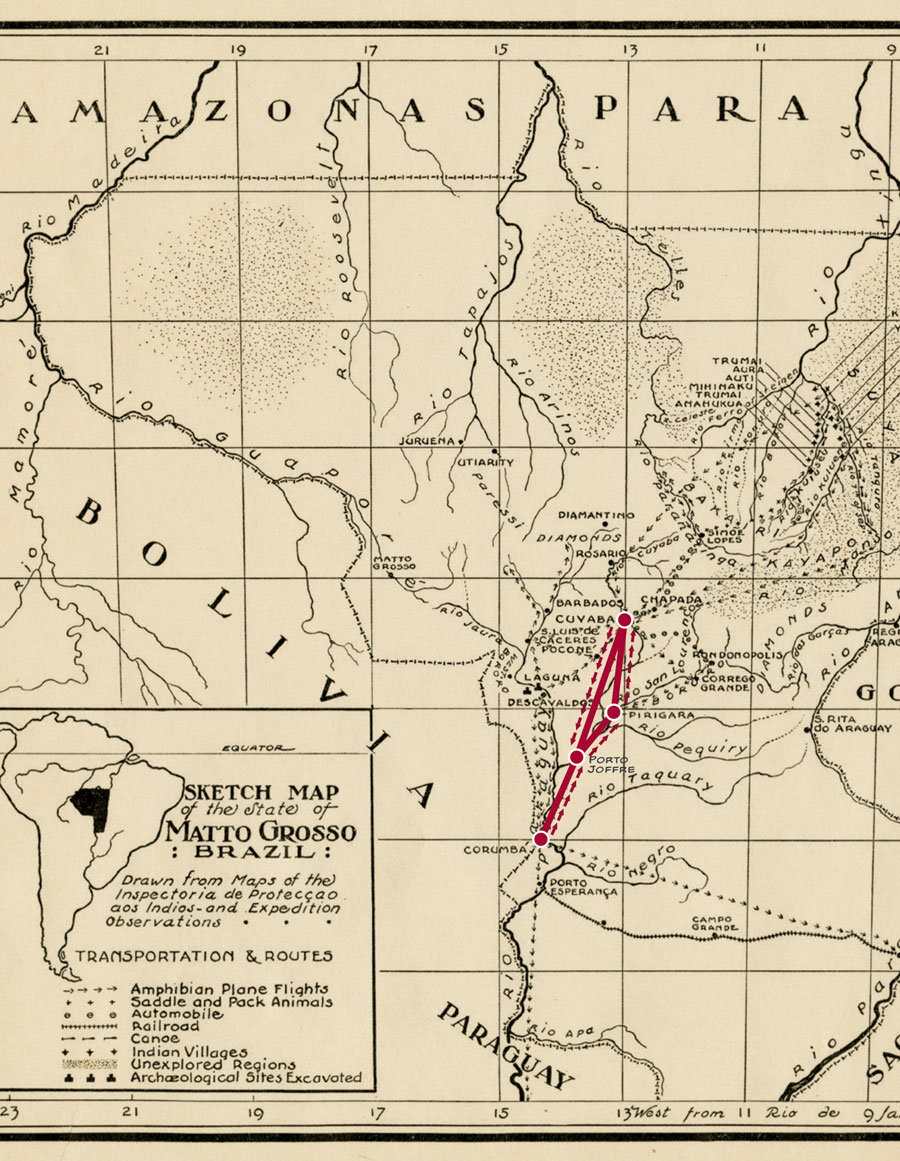

Following his latest border-mapping expedition (1927– 1930), Rondon was in Matto (also spelled Mato) Grosso State to visit family and friends in Porto Joffre and Cuiabá, inspect his ranch near Rondonopolis, and check on SPI activity. Already one week and 1,500 miles from his Rio de Janeiro home, Rondon’s in-state itinerary would require two to three weeks (the 4,000-mile round-trip would take two months). However, when the Matto Grosso Expedition heard the general was in Corumbá headed to Cuiabá, Johnson telegraphed an offer to fly him to Cuiabá, promising a two-hour flight rather than a weeklong riverboat journey. Rondon realized he could save weeks of travel and satisfy his curiosity about flying, but accepting this offer meant acting on this group’s requests for help.

After Teddy Roosevelt, in his book Through the Brazilian Wilderness (1914), credited his survival on the Roosevelt-Rondon Expedition to the general, waves of North Americans had visited Rondon to meet a “hero,” copy his maps, secure his blessing to “explore” Brazil, or try to include him in business schemes. Rondon had mastered the art of interacting with wealthy, self-assured North Americans: he was unfailingly polite, attentive, and encouraging; however, believing that Brazilians should lead in-country exploration and development, he was non-committal. His first meeting with the Matto Grosso Expedition on January 8, 1931 in Rio de Janeiro fit this pattern: he listened to their plans, promised help if possible, and wished them well, although he doubted these inexperienced North Americans would accomplish much. Still, since late February, University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Vincent Petrullo, the expedition’s archaeologist/ethnographer, had wired Rondon repeatedly pleading for help in securing permission to visit indigenous communities, carry out ethnographic re-search, and film these off-limits groups. Without federal approval, the expedition had to work at its basecamp on the three-and-one-half-million acre Descalvados ranch, which, although rich in animals to hunt and to film, was not home to indigenous peoples “exotic” enough to entice North American museum and cinema audiences.

Flight Plan: June 12, 1931

Boarding any airplane in 1931 was risky. All flying occurred during daylight hours using rudimentary navigational aids: compass plots anchored to imprecise maps, watch-timed distance gauging, and flying by visual landmarks. Getting to one’s intended destination was never guaranteed. Yet, if the general boarded any aircraft in the world for his first flight, this Sikorsky S-38 was his best option. The aircraft was less than two years old and boasted two Pratt & Whitney engines (the S-38 could fly on one), could land on water or ground, fly 750 miles before refueling, and carried short-wave radios assigned to a trained operator who supported inflight navigation and, if necessary, coordinated rescue efforts. The crew assigned to the Matto Grosso Expedition was world class. Captain Charles Lorber, among Pan Am’s most experienced pilots, was trained to lead a crew out of danger. Co-pilot/mechanic José Sauceda and radioman/navigator Hans Due were cross-trained, multi-lingual (English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese), and assigned to the Matto Grosso Expedition because, like Lorber, they were among Pan Am’s best.

This crew left the Hotel Galileo at dawn Friday, June 12, having each finished a cup of coffee and pocketed a couple of rolls and slices of cheese to eat as they walked from the Corumbá city center atop the 300-foot bluff down to the waterfront, knowing the day would be their most demanding since joining the expedition on May 17. Johnson asked for two, possibly three, flights before dark: they would fly from Corumbá to Porto Joffre so Rondon could visit friends, then continue northeast to Cuiabá. If late-afternoon weather allowed, Lorber would fly Ron-don from Cuiabá to his ranch on the Rio Saõ Lorenço.

The plan fell apart when the crew boarded the air-plane to find that an improvised duralumin patch plugging a gash in the hull had failed. While the crew bailed water under the passenger compartment then resealed the patch, morning passed, skies threatened rain, and Johnson took Rondon to lunch. But, because there is no fast lunch in Brazil, and, as Johnson noted, “siesta time is sacred,” it was late afternoon when the general and Johnson arrived at the riverbank and were rowed to the airplane anchored several hundred yards off shore.

With his passengers settled, Captain Lorber signaled his crewmates to start both engines, then called for Sauceda to lift the anchor. It would not budge, having become entangled on the feed pipe of Corumbá’s water plant. Now Lorber faced another challenge: cut the rope and lose the anchor, or dislodge it. After conferring with Sauceda, Lorber opened the hatch between the cockpit and cabin to tell Johnson he would not leave without the anchor. Johnson, using rusty French, relayed the news to Rondon. Johnson decided he must take charge, and told Lorber he would retrieve the anchor.

Forty years later, Johnson remembered “all of us thought that such a swim, brief though it would be, was extremely dangerous, so naturally I did not feel like ask-ing someone else to do the job. I took off all my clothing excepting my under-drawers and went over the side.” Johnson feared an attack by jacarés (caiman), but after locating the anchor in 18 feet of fairly clear water and seeing no lurking jacarés, he dislodged it and headed up the rope. Halfway to the aircraft he encountered a sight “which…turned my blood to ice water…layer after layer of piranhas around the anchor line…like the spokes of the Statue of Liberty’s crown.” Johnson inched up the anchor line anticipating an attack, crawled aboard unbitten, and remembered his fear was so great that it “had frozen me into speechlessness. I was fully dressed, and the plane was well on its way before I could utter a word.”

New Challeneges Aloft

Above Corumbá, clouds were forming and rain was fall-ing to the south as Lorber leveled the aircraft at 1,600 feet and pointed it northeast to Porto Joffre. Visibility was not great and rising columns of hot, moist air off the Pantanal (tropical wetlands) buffeted the aircraft. The plane bounced, the yoke jerked, and the airframe creaked and rattled. Captain Lorber glanced over his shoulder to check on his passengers and noticed the general looked unwell; the first-time-flyer was airsick. Although he would have liked to help Rondon, that responsibility fell to radioman Hans Due. Lorber’s priority was to spot Porto Joffre in the vastness of the world’s largest wetland. Maintaining his compass heading as visibility decreased, Lorber checked his wristwatch every five minutes to monitor flying time.

The City of Corumbá

The Corumbá waterfront in 1931. Situated on the banks of the Paraguay River, it was originally founded as a Spanish military outpost. Today this historic city maintains an old village district preserving colonial-era architecture, and a modern urban center with two international airports. PM image 25529.

After one hour, Lorber and Sauceda knew Porto Joffre should be below; however, they saw no settlement. The cloud ceiling was sinking, a moist haze distorted all viewing angles but down, and daylight was fading. Certain that his calculations were correct, Lorber turned and tracked the Rio Saõ Lorenço for several miles. Although Porto Joffre was not in sight, Lorber spotted smoke from a shack along a landable stretch of river, then lined up for a mid-river touchdown. He would ask whomever was home for directions.

On contact, however, Johnson yelled that the plane was taking on water—the hull patch had failed again. Lorber returned both engines to full power and seconds later the S-38 was airborne and, although Johnson confirmed that water was draining, Lorber was assessing options: turn west and fly 150 miles to their Descalvados basecamp (and the crew’s full repair kit) or stick to the original flight plan. Because General Rondon was promised air travel to Cuiabá, and Lorber could run the aircraft out of the water there, he headed north. With still an hour to fly, he hoped the light would hold for a safe landing.

The Pantanal Wetlands

Aerial view of the Pantanal region of the Paraguay River, near the city of Corumbá. The Pantanal is a natural region en-compassing the world’s largest tropical wetland area. General Rondon and the flight crew would have witnessed similar views during their 1931 flight. Photo by Pulsar Imagens/Alamy.

Lorber made the turn to put them back on course to Cuiabá as voices behind him announced that Porto Joffre was below. Co-pilot Sauceda confirmed the sighting and Lorber dropped close to the river to look for any debris or boats that would impede a landing in front of the small town. As the plane connected with the river, and Sauceda lowered the wheels, Lorber reduced the engine’s thrust and scouted the loading ramp on which he intended to park. They would overnight in Porto Joffre. After a close call leaving Cuiabá Thursday, and today’s events, he would not risk the plane, crew, and passengers on a twilight landing.

Over dinner, General Rondon told their host, Dr. Otavio Costa Margues, Matto Grosso Secretary of the Treasury, about the day’s flight. Rondon, whom Petrullo recorded “was very enthusiastic about the beauties of the Pantanal,” recounted how different the area he had flown over seemed from the region he had trekked across on foot, horseback, and boat. The region was more spectacular from above. He assured Lorber that despite his inaugural bout of airsickness, his first flight was wonderful, and he looked forward to what he would see between Porto Joffre and Cuiabá.

On to Cuiabá

On Saturday, June 13, the morning’s skies were the best in a week, and takeoff was set for 8:00 am. The passenger list had grown after General Rondon asked to take his friend, Colonel J. Tozzi Galvaõ, who had studied engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, to Cuiabá. The plan was to follow the Saõ Lorenco River east-northeast 40 miles to the Bororo Indian village, Parigara, so Ron-don could check on SPI activity. At Parigara, Lorber flew down the river then pulled up having deemed the land-ing zone “a little too risky.” He circled the village to give his passengers a good view, then set a northerly course to Cuiabá. By 10:00 am, the aircraft was parked at Cuiabá’s docks, the passengers were gone, and the crew focused on hull repairs. These had to be perfect because General Rondon had volunteered to guide them 300 miles northeast to locate indigenous populations for Petrullo’s ethnographic foray.

But Sunday dawned cold and windy, with low, dense clouds. Lorber, who would not fly into the mountains north of Cuiabá in thick cloud cover, informed Rondon that the flight must be rescheduled. On Monday, June 15, Johnson ordered an early-morning round-trip to the expedition’s Descalvados base camp before they flew into the Xingu River basin. While refueling the aircraft after lunch, Lorber was told to squeeze in another flight: General Rondon had completed his business in Cuiabá and wished to return to Porto Joffre.

Rondon’s Gratitude

By the time General Rondon thanked Johnson for the Matto Grosso Expedition’s courtesy, it was clear that ferrying Rondon paid off: he signed travel authorizations for off-limits indigenous territory, opened doors through-out federal and state bureaucracy that had been shut

to the North Americans, and introduced them to the Commander of Cuiabá’s police, Cassal Martins Brum, and to Coronel Leio Da Costa, Chief of Police of Matto Grosso and Secretary of Public Safety. Johnson marveled that Rondon “even brought about cooperation of the Inspectoria,” instructing SPI staff to plot a route into the Xingu River basin. Rondon then corrected the expedition’s maps.

During four days in June 1931, General Rondon amassed approximately 800 air miles. Although he may have remembered his first flight for the panorama outside his passenger-cabin window and his first bout of airsick-ness, Rondon also experienced uneventful take-offs and landings, had a front-row seat to two aborted landings, two safety-based schedule adjustments, and witnessed on-the-scene repairs. Although he would fly again, cross-ing South America on diplomatic assignments, General Rondon entered the aviation age and viewed Brazil from above alongside the Matto Grosso Expedition.

Radio Operator’s Son Donates Papers to Museum

In 2018 the Museum Archives hosted Hans F. Due, Jr., son of the radio operator on the Sikorsky S-38 amphibian airplane flown by Charles Lorber on the Matto Grosso Expedition.

Hans Frederick Due, Sr. (known as Fred) was born in Norway in 1902 and moved to the United States in 1915, at the age of 13. In 1930 he joined the fledgling Pan American Airways as Flight Operator. One of his first missions was on the Penn Museum’s Matto Grosso Expedition, related in this issue. Due’s role on the expedition included operating the radio and remaining in contact with the expedition base at Descalvados, a large ranch at the headwaters of the Paraguay River. He also assisted the Brazilian radio operator while at the base and reported schedules to Rio de Janeiro, Belém, and New York City. Fred Due is seen in the Matto Grosso film starting the engine of the plane.

Fred Due continued to work for Pan Am for another 20 years. In 1978, 47 years after the expedition, Due typed an account of his involvement on the expedition, which he hoped to publish. He died two years later, in 1980.

It was only after his father’s death that Due’s son, Hans, Jr., learned of his participation on the expedition. Last year, after being contacted by Eric Hobson, who is writing a history of the expedition, Hans decided that his father’s story needed to be preserved. He traveled to the Penn Museum to donate his father’s manuscript, as well as photographs, letters, and his father’s telegraph key, most likely the one used on the expedition.

It is remarkable that his father’s most memorable trip was on the Matto Grosso Expedition, and these are the only records kept by this quiet and self-collected man. The Penn Museum Archives is grateful to both father and son, one for his contribution to pioneering research, and the other for his far-sightedness in preserving this story.

ERIC HOBSON, PH.D., is a Professor in the Department of English at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee. He is writing a book on the Matto Grosso Expedition.

For Further Reading

Pezzati, A. with D. Sutton. “The Present Meets the Past,” Expedition 51.3 (Winter 2009): 6–9.