“Lock of hair from the skull of the skeleton” was penned in a bold 19th century hand across the lid of an old yellow and red cardboard box used to store visiting cards. Crouching over the drawer, I pulled it out. Could it really hold ancient hair from an Italian tomb? Sometimes discoveries occur in museum basements rather than in the field. This particular discovery was made in 1999, as I rummaged through Penn Museum storage drawers in search of objects for the new Etruscan and Roman Galleries (opened March 15, 2003).

The card box had been used by Arthur Lincoln Frothingham as he traveled through Italy collecting material from excavations for the nascent Free Museum of Science and Art (now the Penn Museum). He had contracted with Francesco Mancinelli Scotti, an Italian archaeologist, to excavate a series of tombs in the Iron Age necropolis of Narce, in the territory of the ancient Faliscans, an Italic culture on the west bank of the Tiber north of Rome. The new acquisition had been a serendipitous find of 1899, when workmen quarrying sand on a hill near the town of Civita Castellana (ancient Falerii) crashed into a chamber tomb beside the road to Centumcellae.

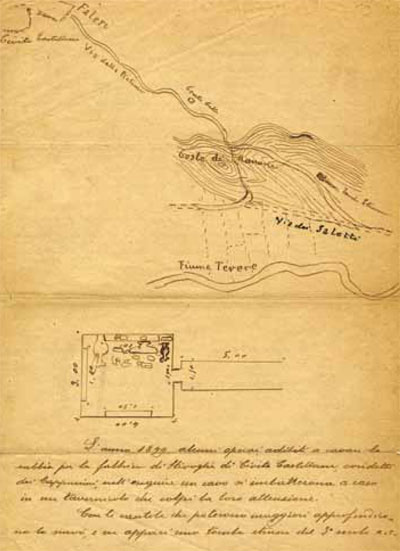

My investigation of the lock of hair began when Penn graduate student Valentina Follo helped me decipher the 19th century handwriting describing the accidental discovery. The locale was known as Cogion, or Contrada Coste di Manone, a necropolis of ancient Falerii. The tomb was rectangular (3 x 4 m) with three loculi, bench-like shelves, cut into the side and back walls; one in the right wall remained intact, sealed with four large terracotta tiles. The workmen gingerly lifted aside the red tiles and gasped: there lay an undisturbed skeleton with tatters of cloth clinging to it, as well as clumps of wavy, reddish hair adhering to the skull.

Mancinelli Scotti’s letter, written in Rome on July 29, 1900, describes the skeleton as resembling terracotta, like the tiles that protected it (the organic remains are stained this color). He also observed that all the hair, including pubic hair, was preserved; hair on the skull was completely covered with a woolen textile (now thought to be linen). The letter exclaims: “In the necropoleis of Narce and Falerii, more than 1000 tombs have been explored, and never has it ever happened that skeletons were found that preserved the hair, coverings or clothing…”

Although Mancinelli took great care to remove skeleton, hair, and cloth with the least possible damage, the remains dried out disastrously overnight, and the deterioration could not be halted. Frothingham, under orders from the Museum committee to acquire historically significant material, including skeletons, hastily saved a handful of hair and, in the second of his card boxes, a piece of cloth with hair still trapped within it. What arrived by ship in Philadelphia in October of 1900 was a skeleton or perhaps only the skull, and two small boxes containing a desiccated sample of wavy hair (Museum Object #CG 2004-6-2) and a small piece of twisted fabric, similarly stained an orange-brown (CG 2004-6-1).

Two vases were sent along with the skeleton and organic samples. These had been found with 10 other vases on the floor of the tomb and are the only reliable indicators of the date of the burial. One of the Late Faliscan Red Figure cups (MS 3444) depicts the joyous embrace of Fufluns and Ariatha—Bacchus and Ariadne, who would marry the god and gain immortality by passing through mortal death. The style of the painted vases indicated the burial occurred ca. 350 BC.

The strands of hair are approximately 8 cm long, and broken at one or both ends, thus no longer the original length. The very fine hair falls in irregular waves; it likely was originally dark in color, and had naturally bleached to red during burial.

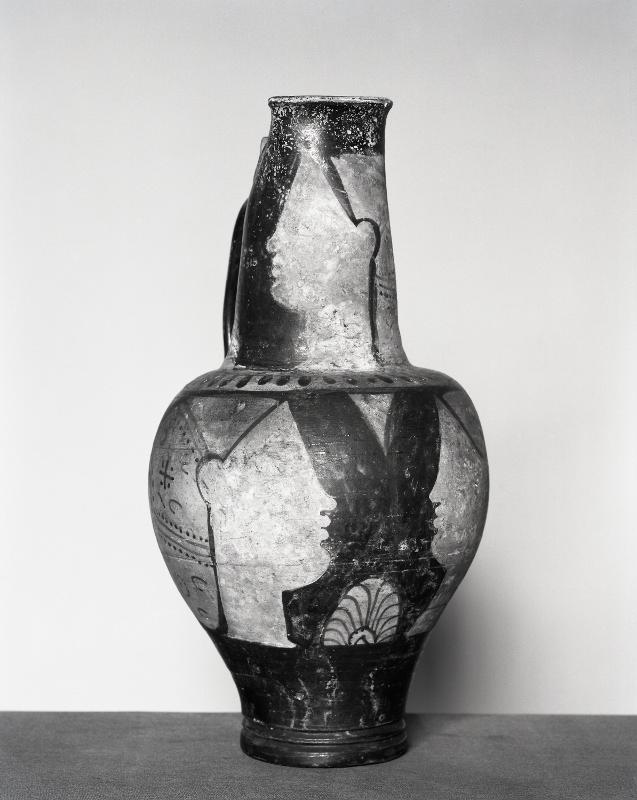

On a visit to the Penn Museum in 2005, Dr. Adriana Emiliozzi (Centro Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome) realized what the scraps of cloth really were. They represent a short-lived Faliscan and Etruscan fashion, the full sakkos , a snood or hair covering that is depicted on numerous vases. One cup buried with the woman in the tomb depicts, in very hasty paint strokes, a plump female head wearing this very head-gear (MS 3445). Another vase, a jug (MS 2518) from the Penn Museum Collection unrelated to the Cogion tomb, also depicts a snood.

Museum Object Number: MS2518

The textile fragment is a gauzy plain weave, with one edge folded over and sewn very evenly with purple thread; the base textile and stitching have been provisionally identified as linen by Dr. Margarita Gleba, Marie Curie Fellow at the Institute of Archaeology, University of London. The ample folds and plain weave are consistent with the construction of the large, bag-like sakkoi depicted on the vases. They seem to have been decorated with embroidered borders, and the simpler purple line of the edge of this piece was intended to be seen. In some images of these hair coverings, there is even an extra hole with a ponytail protruding from it; others show a tendril of curled or wavy hair escaping the sakkos in front of each ear, and the wavy hairs trapped in the bunched folds of the Cogion textile could represent that hairstyle.

The hair and cloth have been scanned by microscope and XRF, and are still undergoing study, testing, and conservation. A few hairs have been shared with scholars in London and Copenhagen (Prof. Adrian Harrison of the University of Copenhagen Veterinary School), where isotopic and DNA analyses are planned.

When the ship docked in Philadelphia in 1900, the Free Museum was far from completed, and storage and display space were in short supply. The skull to which hair and sakkos belonged was stored separately and is missing. We hope to one day reunite the fashionable Faliscan lady with her headdress. She would have been pleased to know that Museum visitors and researchers recognize that she was buried in the height, however fleeting, of fashion.

Jean MacIntosh Turfa is a Rodney S. Young Fellow in the Mediterranean Section of the Penn Museum. She is the author of Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum, 2005).

Further Reading

Gleba, M., and J. MacIntosh Turfa. “Digging for Archaeological Textiles in Museums: ‘New’ Finds in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.” In Archäologische Textilfunde—Archaeological Textiles. Proceedings of the 9th North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles, 18–21 May, 2005 , edited by A. Rast-Eicher and R. Windler, pp. 35-40. Näfels: Ragotti & Arioli Print, 2007.

Turfa, J. MacIntosh. Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology . Philadelphia: Penn Museum, 2005.

Becker, M.J., J.M. Turfa, and B. Algee-Hewitt. Human Remains from Etruscan and Italic Tomb Groups in the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Biblioteca di Studi Etruschi 48). Pisa, Rome: Istituto di Studi Etruschi ed Italici, Fabrizio Serra Editore, 2009.