Butrint is a place of contrasts. The main archaeological site with its forum and public buildings—described by Virgil as “Lofty Buthrotum on the height”—is shrouded in trees, and is the haunt of exotic birds, butterflies, and woodland life. Just across the Vivari Channel that connects Lake Butrint to the deep blue Ionian Sea lie the flat grasslands of the Vrina Plain, a savannah roamed by fierce beasts—shepherd dogs which are descendants of the Molossian hunting dogs of antiquity.

This Albanian site has been the subject of extensive archaeological investigation over the past decade. Here the town meets countryside, with remains that span the 1st to 13th centuries AD. Examination of soil columns from the Vrina Plain, originally part of the once much more extensive Lake Butrint, reveals a complex history: successive episodes of open water, subsequent marsh formation, followed by forest, succeeded by marsh once again, and finally a thick layer of alluvial silts due to periodic flooding of the lake. It was this rather uncertain tract that was chosen by Emperor Augustus’s engineers to be the core of the colony laid out after 31 BC.

This landscape was reclaimed and transformed into plots of land by Roman land surveyors, who also built a half-mile long bridge connecting this area to the town; beside the bridge, an aqueduct took sweet water from a distant spring into the city. By AD 150 the settlement and streets gradually coalesced into a series of large townhouses, villas, and monumental cemeteries along the water frontage.

One of these villas is the subject of the current excavations and also the location of the annual Albanian Heritage Foundation’s field training school, generously supported by the Packard Humanities Institute in collaboration with the Butrint Foundation. This year the school was attended by Albanian undergraduates from Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, and, as a result of collaboration with the American University of Rome, the United States. The Summer School started in 2000 and was run by foreign specialists; now it is directed by its Albanian alumni.

This is not the first villa to be examined at Butrint. Like the other villas excavated by the Butrint Foundation, it was situated on a shoreline. Here, though, instead of uncovering the grand residential rooms, the Summer School has concentrated upon areas that were used for agricultural and productive activities.

A geophysical survey revealed the extent of the property, stretching back from the Vivari Channel and demarcated to the south by an elaborate ditch system. This villa almost certainly belongs to the age of Nero (1st century AD), when he oversaw major investment in this region, as well as in areas further to the south in Greece. Several seasons have been spent examining the northern part of this complex where a sequence of rustic buildings were found, including a detached bath house along the eastern side of an open yard, which may have been used by estate workers. Like all the properties in the shadow of the town, building occurred at regular intervals throughout the 2nd century until the early 3rd century AD after which, as elsewhere at Butrint, there was a significant economic downturn. Several service buildings were abandoned and later reemployed for a family burial cult; a substantial mausoleum was constructed, which faced a massive stone platform, itself most likely having a funerary function. A gold coin from the 4th century AD—a solidus of Constantine II—was recovered from a grave cut into the surface of the platform. Creating a cult center for family burial rites is a phenomenon well known from a number of Italian sites, from Imperial villas to the farms of the country gentry. It is a sign of confidence in the establishment of a dynasty and family tradition. The mausoleum was modeled on a small temple, with freestanding columns, a portico, and a high central chamber to accommodate several sarcophagi and tombs. During the 200–300 years of its life, burials were inserted into almost every nook and cranny.

In 2011 we also excavated a building on the southern side of the yard. This was a barn-like structure, with a portico and substantial doorway leading into what was originally the yard. With the building of the mausoleum, the portico and entrance were blocked off, closing access as well as the view onto the funerary space, though the building itself continued in use. After AD 235 a small wine processing facility with a pressing floor was created in its southeast corner, where plentiful remains of dolia, the gigantic storage jars normally partially buried, were found.

Thanks to its agrarian activities the villa certainly continued a rather precarious existence during the troubled span of the 4th century AD and, as elsewhere on the Vrina Plain, there was a modest revival in the 5th century with some rebuilding. However, evidence of 6th century burials within rooms of the building—some of which cut through walls—made it clear that here as elsewhere at Butrint, the villa was deserted after nearly 500 years of occupation.

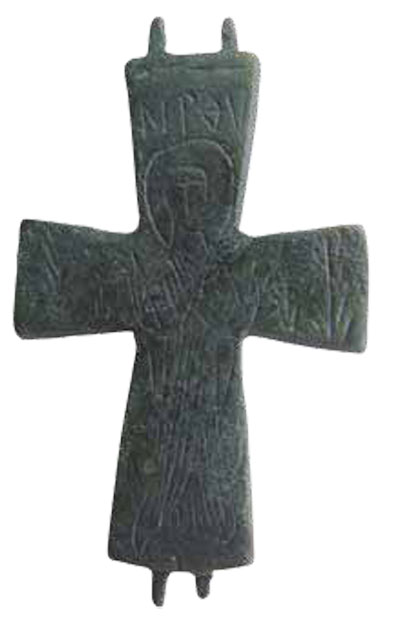

This prominent shoreline ruin was to have a distinguished afterlife. A medieval rubbish dump from the 11th or 12th century contained fragments of high-quality glazed dishes from the Peloponnese, a decorated bronze reliquary cross, and other objects that may denote an aristocratic dwelling and family church. Another such property including a chapel was excavated to the west a few years ago. It is likely that the two sites shared a similar history until the 13th century. At this time, a period of flooding forced occupants to flee the Vrina Plain for the walled town of Butrint. The Vrina Plain became a marshy expanse and remained unaltered until the communist government drained it in the 1960s.