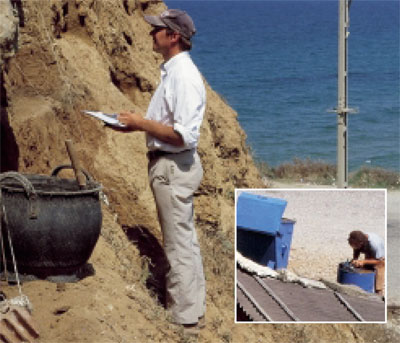

During the summer of 2000, in Sinop, Turkey, a hot noontime sun beat down on a small field crew consisting of Drs. Fredrik Hiebert and Owen Doonan, Black Sea Trade Project director and field director, respectively, and me. The three of us clung, by various means, to the sides of the small scarp we were excavating, located at the base of the ancient city walls of Sinop overlooking the Black Sea. Breezes from the nearby sea were warm and carried the dirt loosed by our excavations, stinging our eyes and caking our skin and hair.

A bit uncomfortable? Perhaps. But any archaeologist with an ounce of experience knows that these conditions are nothing to complain about. Sinop is the perfect spot for investigating ancient trade. Its harbor has been important since Greek times, possibly much earlier. And the view is truly amazing — small waves crashing against the rocky coastline and a portion of the remains of the city wall. No one was complaining.

Adding to the movie-like atmosphere was the presence of a National Geographic film crew and magazine photographer. We were in the movies. We welcomed the media attention that our project was — and still is — receiving, even though it meant that our already short season was further truncated by on-camera interviews and day trips to the most scenic spots in the neighboring countryside. Still, no one was complaining.

Just after midnight three weeks later, I was nearly being tossed across the slippery deck of a ship in the darkness of the Black Sea. I hadn’t slept more than four continuous hours in over a week, and in front of the film crew that recorded everything I was doing 24/7, I was struggling to carry a large plastic container full of seawater across the rolling, wet deck — and to look graceful while doing it.

How did I get from my beachside excavation to the middle of the stormy sea? The answer: Dr. Hiebert and I are the only two people to work on both halves of this multidisciplinary project that bridges land and sea. After participating in the land excavations in Sinop just a few weeks earlier, I had returned to the States and had no plans to take part in the 2000 field season’s underwater work. A single, cryptic email sent from the project’s research vessel located off the Turkish coast called me back into action; things were hopping in the Black Sea and because of other obligations, Dr. Hiebert had to leave for home. I was the logical choice to take his place.

On the ship, we used sonar and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to explore the sea bottom. Machines don’t need to sleep, so our work went on around the clock, with three crews taking eight-hour shifts. Because of my responsibilities as stand-in chief archaeologist, in addition to my regular shift I was on call at all times. Adding to the drain of the schedule was the need to again work with members of the press. But this time, the media coverage was not entirely welcome. Because of a book titled Noah’s Flood, by Columbia geologists William Ryan and Walter Pitman, our research had become associated with the idea that a flooding of the Black Sea 7,500 years ago may have been the flood event described in the Bible. Our discovery of the remains of a possible preflood habitation site now under nearly 100 meters of water — attracted worldwide media attention. We weren’t looking for evidence of the biblical flood, but working with the media can be like a game of whisper down the lane: You tell your story, but you can’t control what comes out the other end.

To make things even more complicated, we predicted that in the oxygen-depleted waters of the Black Sea, ancient organic materials would be well preserved. Specifically, we expected to find an ancient shipwreck that still looked like a ship (no, not Noah’s Ark!) rather than the typical pile of clay amphorae with the surrounding ship long eaten away. At this point, the project was nearing the end. Dr. Hiebert was gone, and Dr. Robert Ballard, director of the Black Sea underwater research and best known for discovering the Titanic was about to follow suit. Our most significant find to date was an amphorae pile with a number of wooden timbers strewn throughout. The onboard members of the media were asking me if this was the best we could do.

Finally, in the cold and damp early hours of the morning, after Dr. Ballard had boarded a plane for the States, we found it: a nearly intact ship sunk into the seafloor with its mast still rising majestically from the hull. Radiocarbon dating told us that our discovery was approximately 1,500 years old. After a hectic, stormy, stressful, and high-profile season at sea, no one was complaining.

Two years later, in 2002, we proved that our masted wooden ship was not an isolated find: we found an even older well-preserved ship. And as this article goes to press, we are in the midst of another season, taking newly designed ROVs on their maiden voyage as we begin to excavate our deepwater sites.

So keep an eye on the news. I’m sure the press will be keeping an eye on the Black Sea.