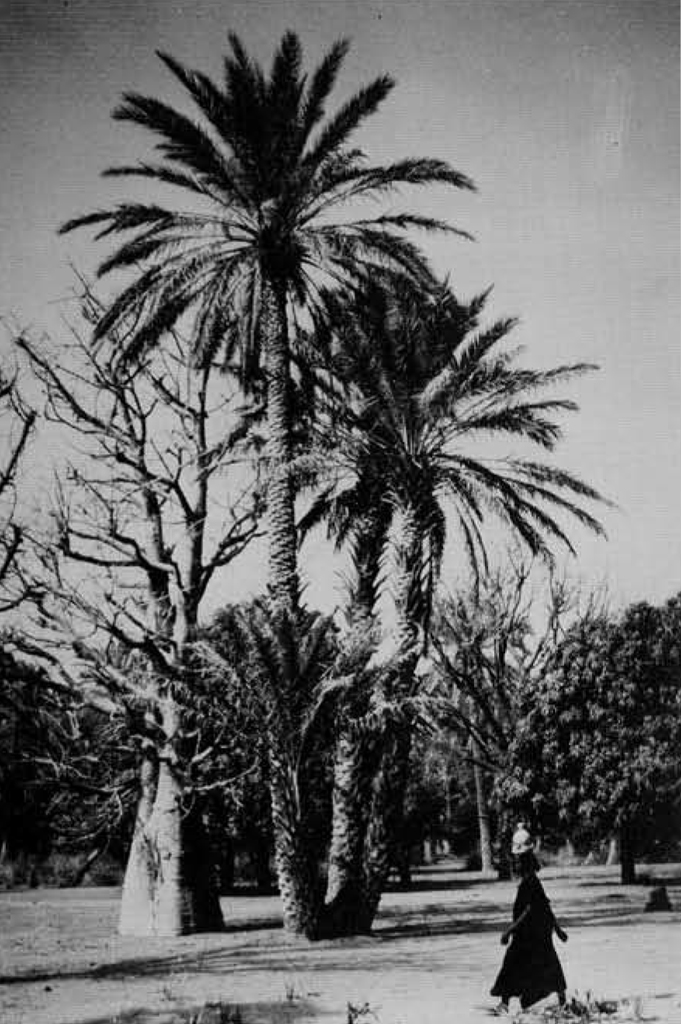

Several women huddled together in the shade of old trees in a small open market. They sat on the sandy ground, selling their sour milk and butter from large brown bowls. The scene had become a familiar one to me during my year of teaching and travelling in Nigeria’s northern states. A few months earlier I would have strolled on by, observing only the colorful attire or the variations in the women’s facial markings. Now I paused, anxious to examine the beautiful artwork that lay on the ground at their feet. I scanned the bowls from which the women were selling. Stooping down beside one lady, I leaned over so that I could see the outside of the gourd shell container which rested on the ground in front of her.

“Kwarya, da kyau (Your calabash is beautiful),” I commented, using a few words from my limited Hausa vocabulary.

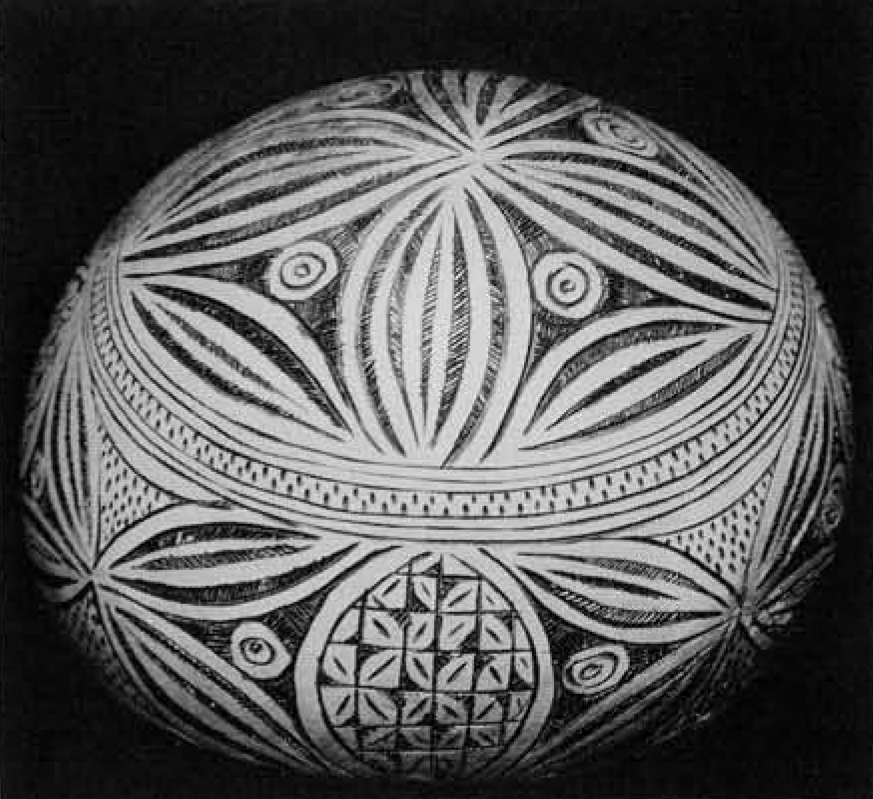

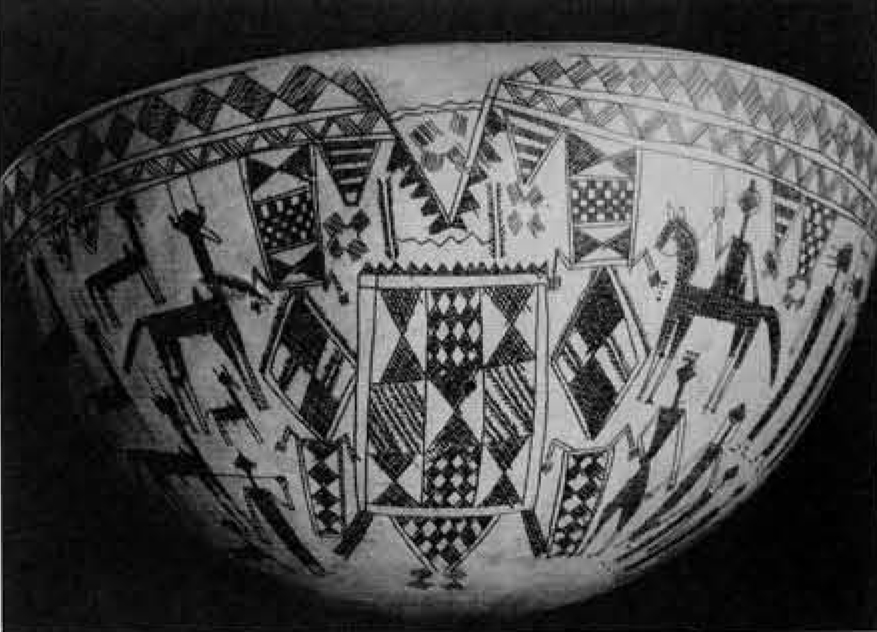

She smiled approvingly as I raised the calabash above my head and turned it slowly to observe the decoration. Dark etchings of tiny animals and people mingled with abstract motifs in a beautiful pattern (1), the designs contrasting delicately with the golden-brown surface of the calabash shell.

“Your calabash is beautiful,” I repeated. The proud owner gazed lovingly at the bowl in my hands.

I proceeded from one woman to the next so that I could examine their calabashes too (2). It was fascinating to realize that these bowls had literally grown on vines. The bowls had been made from the hard shells of dried gourds (of the squash family) and had been beautifully decorated by skilled artists in the Bororo style.

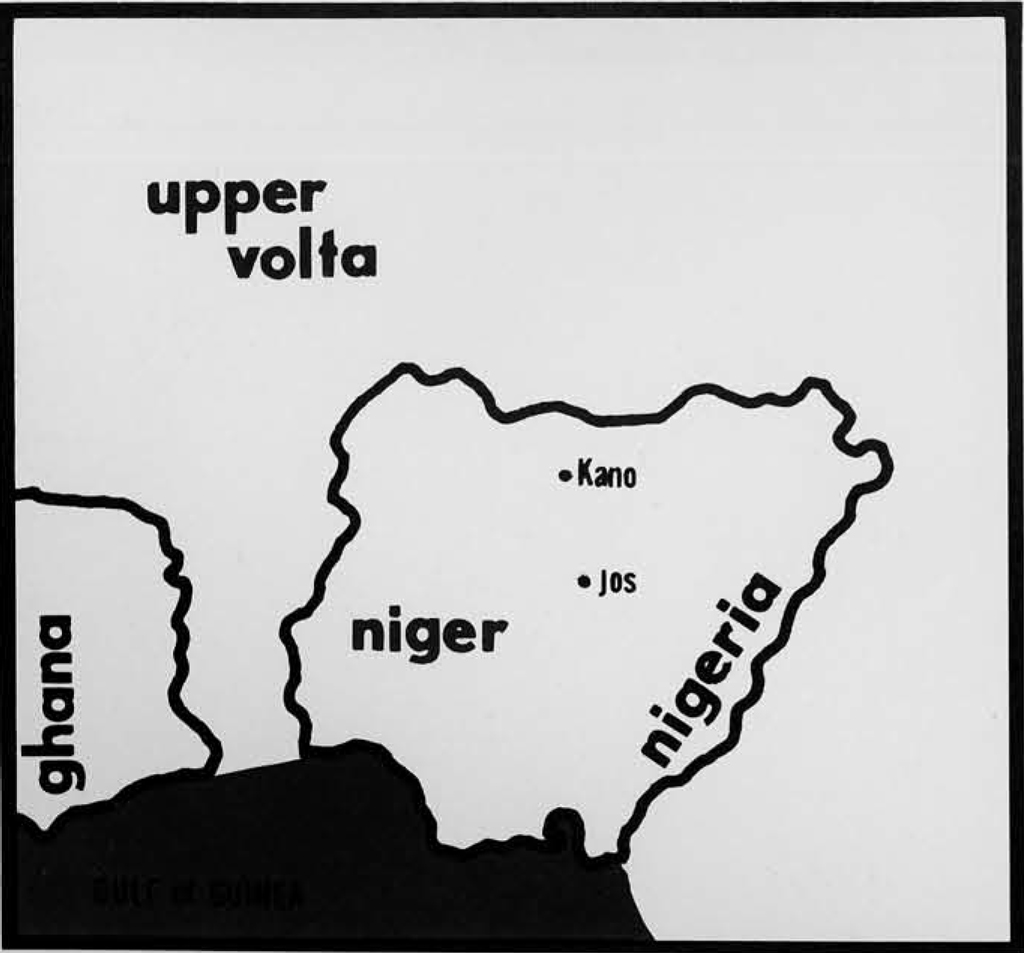

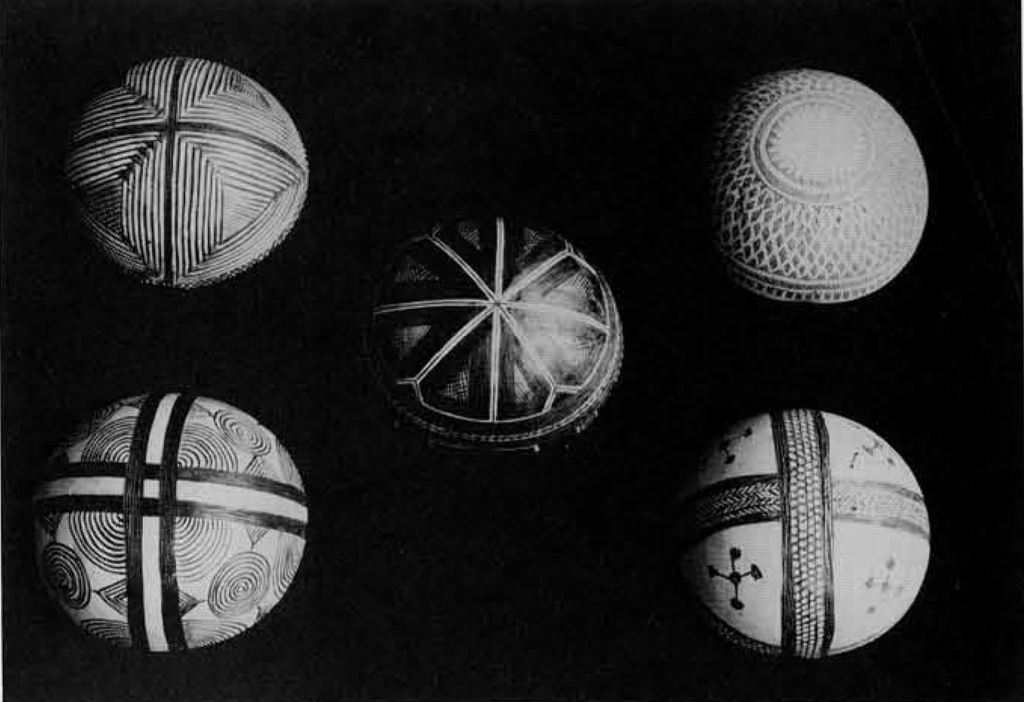

Calabash containers have been used in Nigeria for hundreds of years (3, 4). During this time, different peoples developed distinctively different ways of carving and coloring them. The wide variety of designs and visual effects makes it difficult to believe that each artist started with the same plain golden-brown calabash hemisphere. There is great diversity, even in towns and villages just a few miles apart, reflecting the diversity of the inhabitants and nomadic visitors.

Hausa calabash carvers cut away portions of the outer surface of the gourd in forming their designs. Abstract patterns are usually chosen but sometimes these are intermingled with the shapes of animals or birds. When the carving is completed, the whole surface of the calabash is rubbed with a chalk-like substance to produce a dusty white overall appearance with light contrast (5).

Tera and Bura artists create a darker effect with much more pronounced contrast. Lines are burned into the surface of the calabash with red-hot knives. The deep black designs engraved by this technique provide a rich contrast with the golden-brown of the calabash shell (6, 7). Sometimes the shell itself is first dyed a deep reddish-brown and then oiled repeatedly over the years until it assumes the well-seasoned texture and sheen of fine rich leather.

More delicate designing is created by the Ga’anda and Hona peoples. Their carvers rub a mixture of oil and soot into shallow incisions carefully cut into the calabash surface with a sharp knife. Although Ga’anda and Hona artists employ the same basic technique of calabash decoration, their use of space in achieving designs is quite different. The Ga’anda style is to arrange geometric shapes somewhat formally against a plain background. Hona patterns incorporate open motifs within flowing designs. Also, while Ga’anda women frequently dye their calabashes red, Hona women prefer to leave theirs the natural yellow color and watch them darken gradually from handling and oiling over years of constant use.

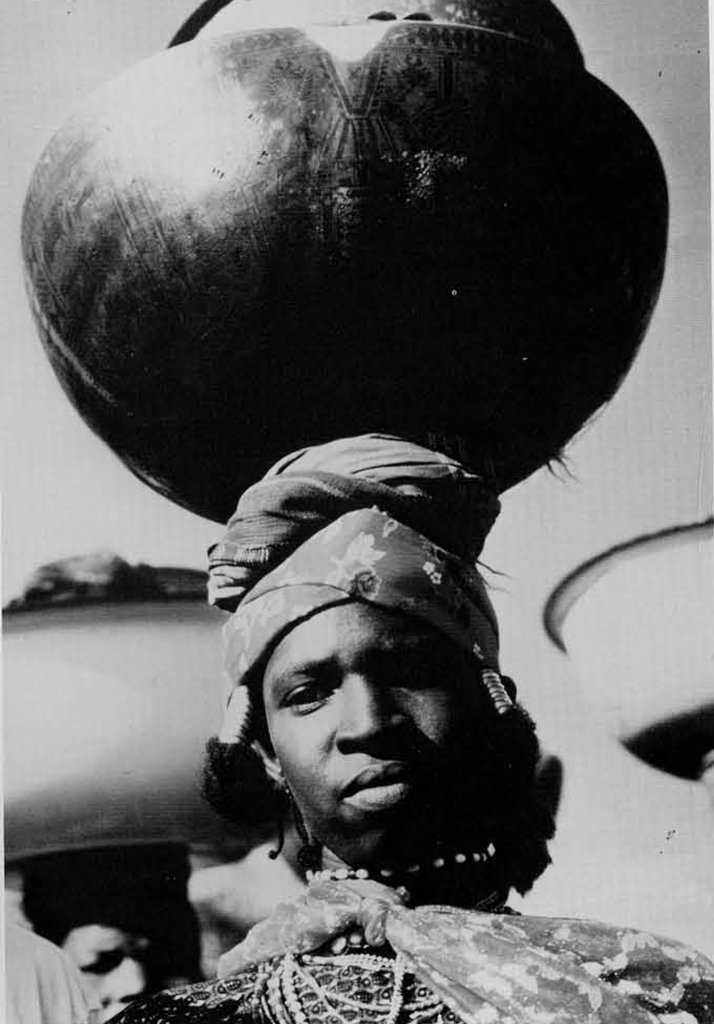

The style of calabash decoration among certain Fulani peoples living in parts of northeastern Nigeria is equally distinctive. Calabashes are dyed a deep red or orange and then thick, black geometric patterns are engraved with hot knives. The resulting design is bold and strikingly beautiful (8).

Occasionally a calabash is decorated by simply pressing a pattern on the maturing gourd while it is still growing on the vine. In this way, the design is only slightly impressed and the effect, a subtle contrast in shades of amber, may be only barely discernible (9).

Nigerian calabash artists have created an almost infinite variety of beautiful and unique designs (10), but their patrons are ordinary country folk and their works of art have not received widespread recognition. In 1973, the principal museum in northern Nigeria, located in Jos, was exhibiting only a modest collection of decorated calabashes and provided no information on the peoples, artists or techniques represented. Some books on Nigerian art and crafts ignore calabash decoration altogether—or devote very little attention to it. Similarly, museums outside Nigeria show little awareness of or interest in these beautiful but ordinary items of day-to-day living.

Perhaps calabashes have been largely ignored because they are so much a part of the way of life. Unless one makes a special effort to look for them, they may scarcely be noticed. Once interested, however, I found that I could be surprised almost daily by the versatility of gourds and the resourcefulness of Nigerians in using them.

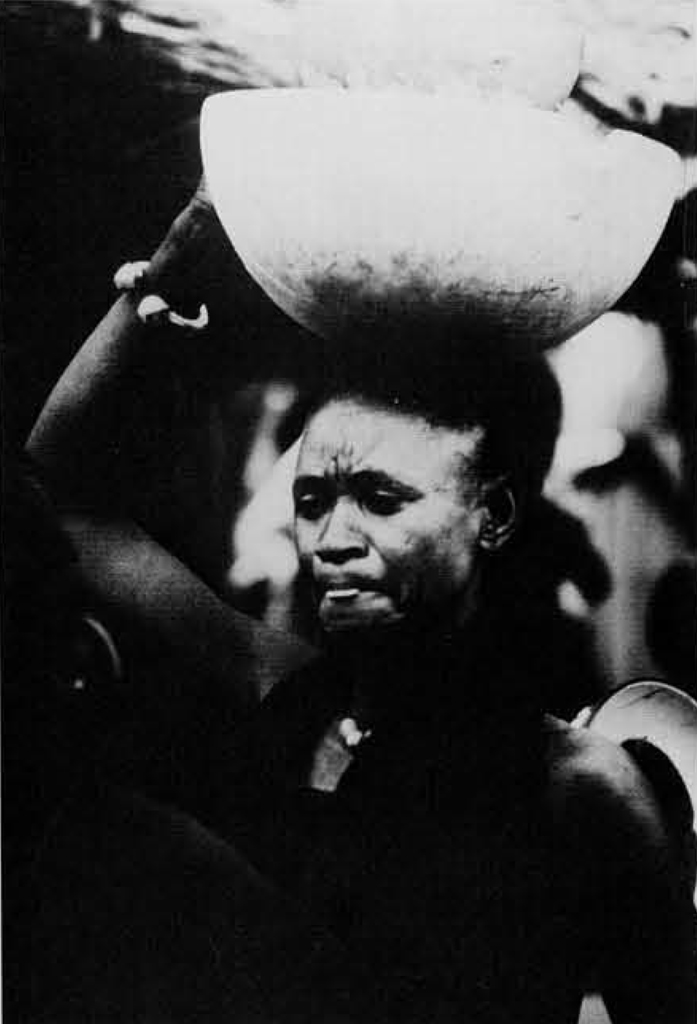

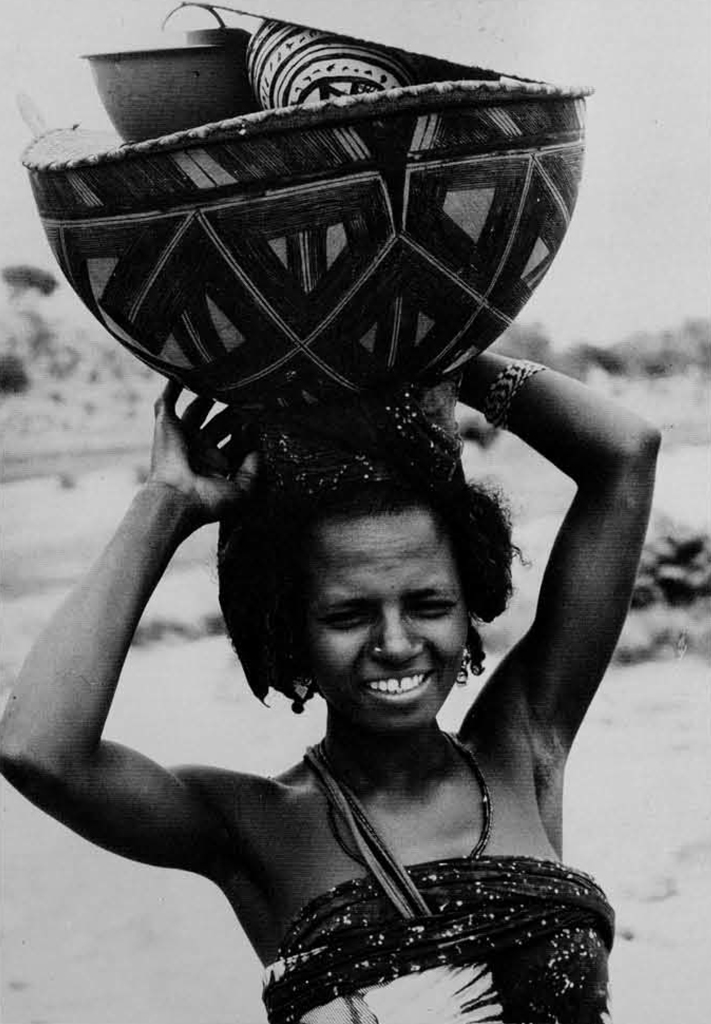

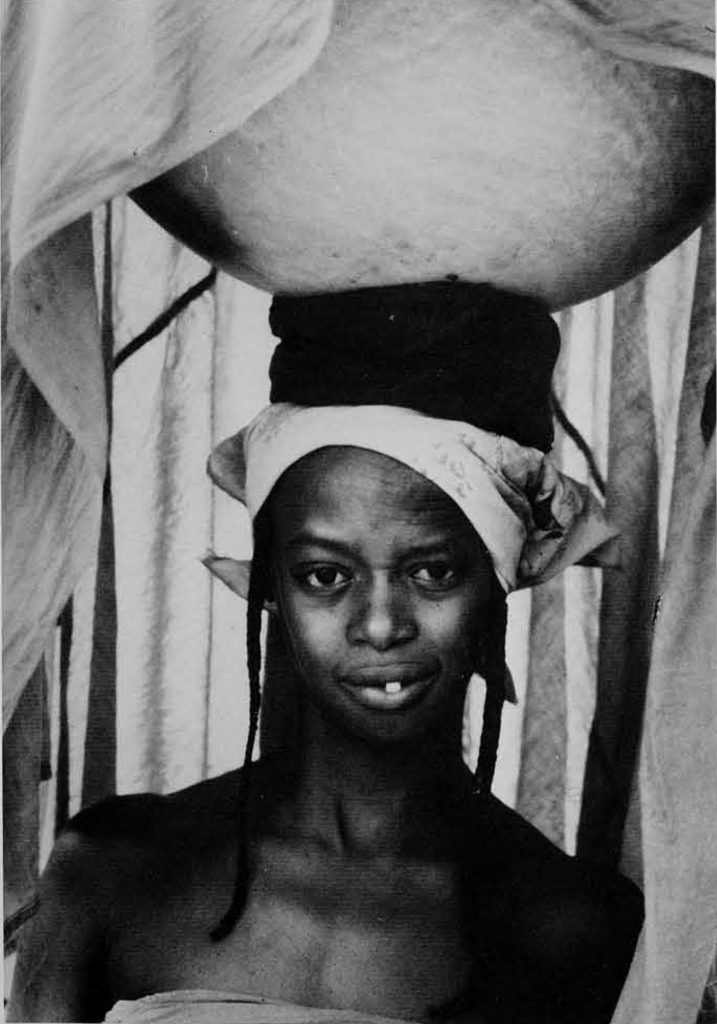

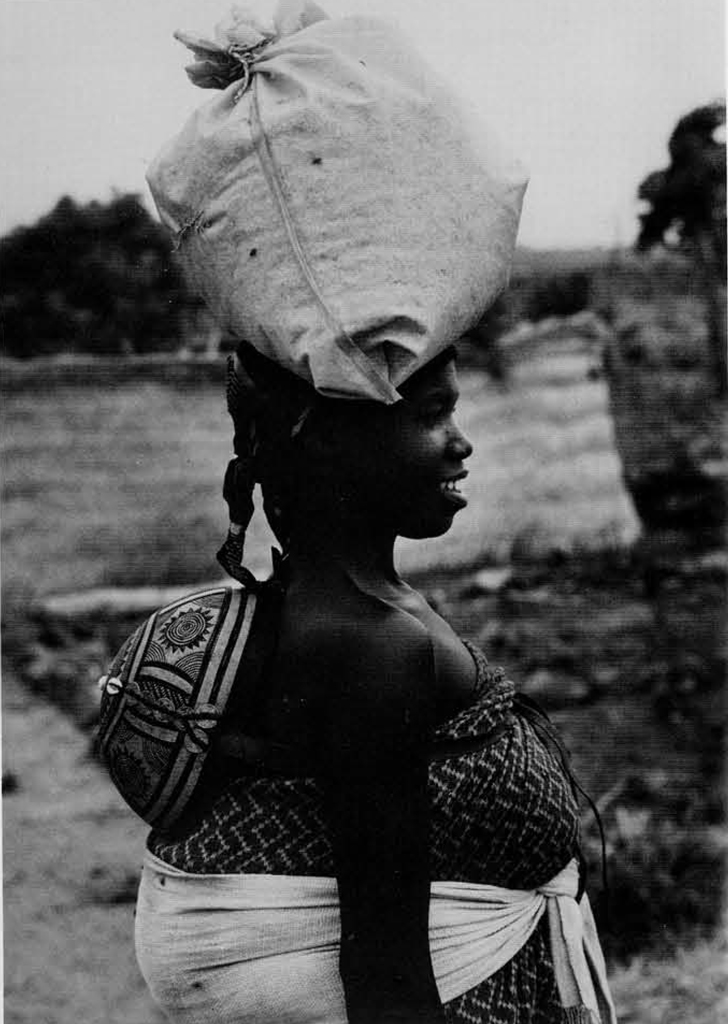

Women often walk along the roadside on their way to market with large decorated calabash bowls on their heads (11). While this is a common activity, the detail of the scene is nonetheless fascinating. Each woman appears to walk effortlessly in spite of the fact that she is carrying perhaps as much as five gallons of milk in her calabash and, in addition, usually has a baby tied to her back. Only a few facial wrinkles may betray the fact that her load has considerable weight. The calabashes of milk are covered with woven straw mats on which other calabashes or pans may rest, On very hot days, a woman may drape a long cloth over her large calabash to form a hanging umbrella shielding her from the sun (12).

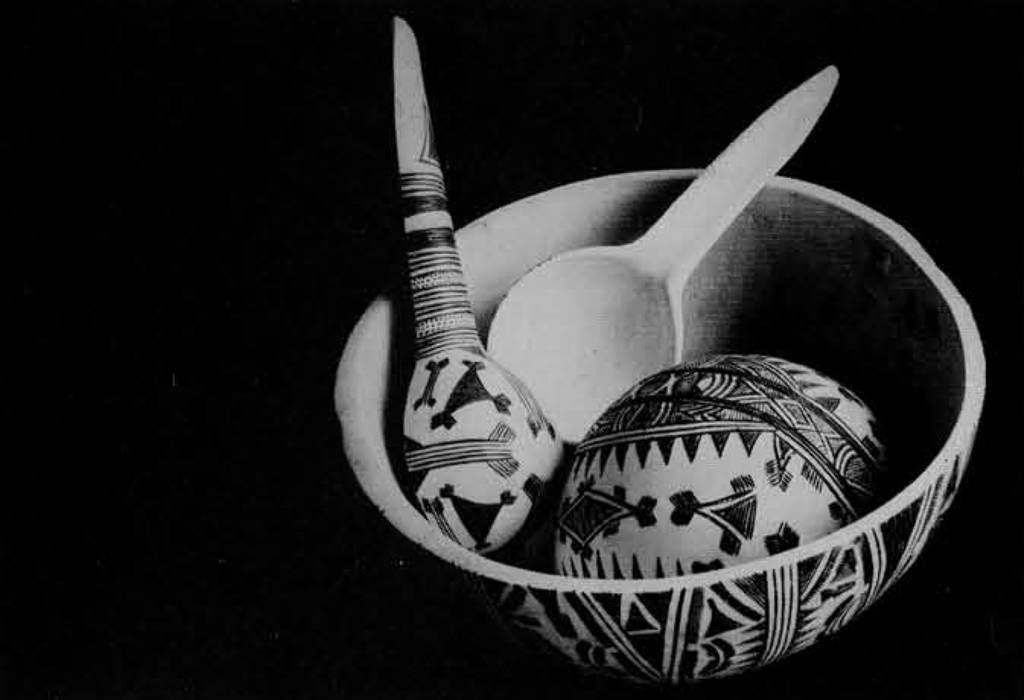

In the marketplace, grain, rice, peanuts and freshly prepared foods are sold from calabash containers. Since the containers usually rest on the ground when they are not being carried, the decoration cannot always be seen easily. Occasionally an empty calabash is turned upside down to form a little stool on which a woman may sit. Men carry calabash jugs of palm wine or water tied to their arms with leather straps. Elongated calabashes are sold for cosmetic purposes. Women use them as containers for a dye made from henna leaves. By dipping their hands in the dye and holding them there for a time, their hands and fingernails are colored red. Calabash spoons, rattles and bowls are sometimes displayed by traders along with Leather crafts and woven baskets. Although these are sometimes decorated especially for tourists, similar calabash items are used in most households in the north.

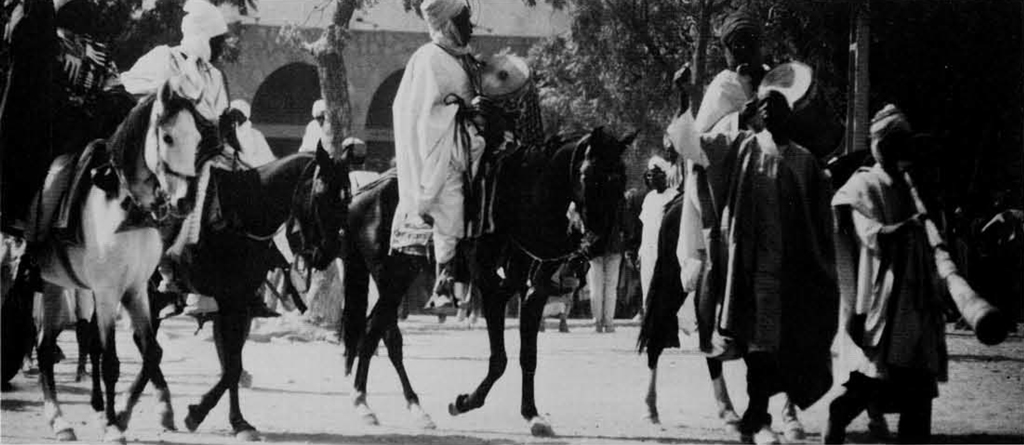

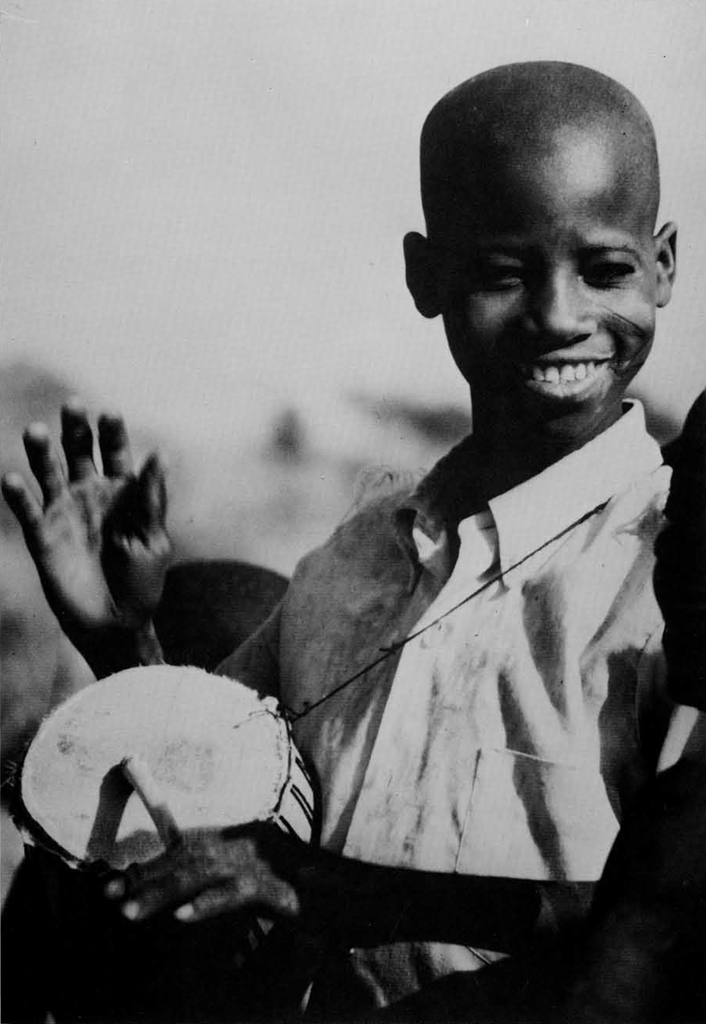

Gourds of different shapes and sizes have also been skilfully employed in the making of musical instruments. At weddings and other local festivities, many of the instruments played are made from calabashes. Long, narrow ones are fashioned into flutes. Shantu horns, made from cone-shaped calabashes ranging up to six feet in length, are played in parades (13). Bottle-shaped calabashes with loose seeds or stones inside become shakers used in traditional dances. Shakers are also created by stringing a net of cowrie shells or beads around the outside of spherical calabashes. Many different sizes and styles of drums are fashioned by stretching skins over hollowed-out calabash frames (14). When fully-fashioned drums are not available, drum-like sounds may be obtained by hitting small, hollow calabashes. Even banjos are made from calabashes by stretching animal skins over large, elongated, pear-shaped gourds and adding strings. Perhaps the most elaborate musical instrument is the marimba which employs calabashes of different sizes as resonators under the wooden slats of the xylophone-type keyboard.

One time when the calabashes are more highly visible than the people is the Argungu Fishing Festival (15). At this yearly event, hundreds of hopeful fishermen crowd into the river, equipped only with hand-carried dragonfly nets and large calabash floats. The latter bob around and bump together on the river as the nets and men submerge into the dark waters. The yellow and brown floats are made by hollowing out a spherical gourd, leaving a small hole at the top. They are an essential part of a man’s fishing gear. Sometimes a fisherman will ride on the calabash float as he swims in the water. Small fish are temporarily stored inside the float. A big catch is immediately taken ashore, Although calabash floats are usually not elaborately decorated, the fishing festival provides artists with the opportunity to design decorative calabashes which commemorate the activities of the day. Of course, fish feature prominently in these designs sold to festival visitors (16).

One of the most interesting uses of the calabash is found among the Bura peoples of the North-Eastern State of Nigeria. Many Bura mothers still use calabash head covers (dambalam) (17) to protect their babies from the hot sun and flies, The dambalam is often part of a baby’s layette and may be elaborately decorated with cowrie shells and coins as well as engraving, Since babies are typically carried on the mother’s back, leather straps affixed to the calabash enable a mother to tie the dambalam in place covering the head of her baby. Although medical experts are discouraging this custom and a neighboring people, the Tera, recently abandoned the practice, the Bura mothers who use dambalam value them highly.

There are many other uses for the calabash, Women use bottle-shaped calabashes as butter churns. Farmers sow millet or guinea-corn grain from small calabashes. “Beanie-size” calabashes are sometimes used by Moslem men as funeral caps. Foreign residents of Nigeria have discovered even more uses for these ancient fruits; they convert large, decorated calabash bowls into lampshades.

In spite of these many ways in which calabashes are currently used in northern Nigeria, it seems likely that fewer and fewer will be seen as the years go by. In Nigeria, as in other places where gourds have flourished, the arrival of Westerners brought containers made from metal, glass and plastic. Today these materials seriously challenge the role of the calabash. Contemporary markets display brightly colored enameled pans and bowls and many people now use them instead of calabashes. A young girl used to receive numerous decorated calabashes of different sizes and designs as gifts at the time of her marriage; nowadays she often receives brightly colored metal pans, plates and bowls. In the future, it seems likely that calabash containers will increasingly be replaced by metal and other manufactured materials which are desired because they are “modern.”

The declining preference for decorated calabashes among the peoples of northern Nigeria will probably mean that fewer and fewer persons will learn this difficult art of gourd designing in succeeding generations. In some localities accomplished artists have already turned to other activities. In one town I visited, none of the three calabash artists had produced any decorated calabashes during the 1973 season.

Historical records show that in the past, calabashes were widely used in various parts of the world. It is known that gourd containers were common in the Hawaiian Islands and on Easter Island, that calabashes were used in surgery by the Indians of the Sierra in Peru to repair broken skulls and that they were grown in the southern United States by various Indian tribes. Gourds found in an Egyptian tomb have been dated to 3300 B.C. and there is little doubt that they were used as well by the early nomadic Bushmen in Africa.

Today, calabashes are grown and widely used and decorated in only a few scattered places around the world. Northern Nigeria, especially the North-Eastern State, is one of these places. Even in the southern and western parts of Nigeria, calabashes are now seldom seen in the towns and marketplaces. They are still grown, but calabash decoration has largely become a commercial art, adapted to the production of plaques, vessels, baskets and spheres of purely decorative value which are sold primarily to foreign tourists (18).

In northern Nigeria, calabashes remain common in the everyday lives of the people. They are beautifully decorated as perhaps nowhere else on earth and they are cherished by many of the people who still use them (19). But the age of the calabash is passing here, as it has already passed in other parts of the world. The peoples of northern Nigeria are now writing one of the last chapters in the fascinating story of the long association of calabashes with the ancient cultures of mankind (20).