Cambay is a small city, population about 50,000, on the coast of Gujarat state in western India. This name is an English corruption of Khambhat. It is a center for lapidary craftsmanship, its products reaching a market on four continents. The largest of these lapidary undertakings is bead-making, the focus of this paper.

Cambay is a small city, population about 50,000, on the coast of Gujarat state in western India. This name is an English corruption of Khambhat. It is a center for lapidary craftsmanship, its products reaching a market on four continents. The largest of these lapidary undertakings is bead-making, the focus of this paper.

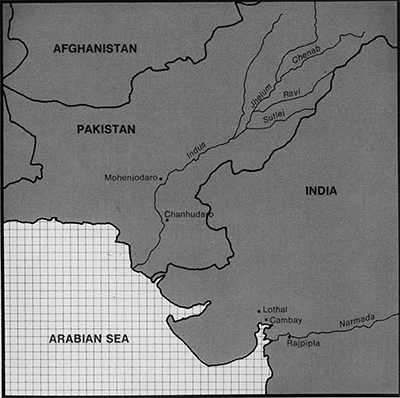

The beadmaking industry is not new in this part of India. The craft seems to have started here as early as the third millennium B.C. with the founding of the Harappan settlement at Lothal (Rao 1973, 1979). This ancient town, which dates to ca. 2400-1700 B.C., had a large scale bead manufacturing operation taking a variety of raw materials —chalcedony and other agates, jasper, rock crystal and the like—and turning them into beads that were used by the Harappans themselves and shipped to places as distant as Mesopotamia. Since the Harappan era the Cambay region, if not the site of the actual town, has been an important commercial center, involving the manufacture and distribution of beads and other products, especially textiles. The historical record is uneven in informing us of the range of activities over this extensive period of time, but we can be sure that the area was always important in commerce between India, Africa and the various parts of Asia and Europe. The bibliography accompanying this paper includes a number of citations which outline this story. Thus, I can move into the manufacturing process and leave history for the moment.

Due to the recovery of extensive bead-working facilities at Lothal and Chanhudaro (Mackay 19431, another Harappan site, we can outline completely the Harappan manufacturing technology. The first step involved a two-phase chipping process which formed the beads to their rough shape. The bead was then ground to a smooth outline. The perforation of the bead was done next. This began with the gentle chipping of a small cup in both ends of the bead. The small indentation was used as a starting hole to steady the drill and act as a reservoir for the cutting abrasive, probably a hard stone grit suspended in a liquid. It is quite certain that the stone drills used in penetrating Harappan beads were propelled by a bow.

It is of considerable interest that this sequence of steps and the same basic technology are still used today in Cambay. There are some minor variations which can be noted, but the similarities are striking. First, however, let me outline the way the modern craftsmen acquire the stone with which they work.

The modern Cambay lapidary industry makes use of stone from most, if not all, of the regions of India and adjacent countries.

Lapis lazuli from the Badakshan region of Afghanistan is as much used as is rose quartz from Tamil Nadu. There are also fuchsite from Karnataka and various corals and other silicious stones from western India. The craftsmen of Cambay use these to make a variety of products. In fact almost anything that one might think of has probably been tried at least once, including ashtrays, paper weights, plaques, cigarette holders, dishes, bowls, spoons and figurines. Thus, while I will focus on the manufacture of beads, probably the most ancient of the lapidary crafts practiced in this region, we must keep in mind that this is only one of the diverse activities in which the Cambay craftsmen are engaged.

There is a sizable body of archaeological and historical information which tells us that the beads manufactured in Gujarat have been made, for the most part, from stone found in the agate beds along the banks of the Narmada River which passes through eastern Gujarat just before entering the Gulf of Cambay. The erstwhile Princely State of Rajpipla has been particularly prominent in the production of this raw material.

The agates are associated with the Deccan Trap of central and western India, a series of Mesozoic lava flows which cover an immense area of the subcontinent. Over the millennia the high silica content stones have been eroded from the interstices of the basalt trap rock, from where they have entered the riverine system. The Narmada, with its immense catchment area, has consequently received a great deal of this material.

There are extensive strata of these agates which have been concentrated by fluvial processes into workable beds of stone. The extraction of the nodules is done with picks and shovels. In the community I visited the work force was made up of teams of three to five men and women. The men dug small holes, about three feet in diameter, to gain access to the agates. The area they were working during my visit was apparently a good one since the lode was struck within about five feet of the surface. Men working with a pick and a hoe-like implement scooped the rocks and earth matrix into metal pans, which were then lifted to the surface. After the pans were dumped near the opening of the access hole, women sorted the valuable agates from the undesirable material (Fig. 2). This frequently demanded that a small ‘window’ be chipped on the surface of the stone to remove the millennia of patina that today obscures the quality of the stone.

There is apparently little effort to expand the mine entrance gallery beyond a few meters in diameter since many abandoned access holes were observed within the area I visited. With the agate beds so near the surface it is apparently worth the small additional effort to start a new access shaft rather than risk a cave-in.

Stones are sorted and graded in a preliminary way at the mine. A second, more careful, sort takes place at the village and the material is then bagged in fifty or hundred kilogram lots for shipment by truck or boat to Cambay.

A fascinating aspect of my visit to the Narmada mines came to light immediately upon my arrival, The people who mine the stones, in this locality at least, are of African descent. Such people are actually more common than one might suspect in western India and Pakistan, especially the coastal areas, where they are called Siddis. This is a result of the lively commerce between India and Africa for at least the past two thousand years.

The Narmada River agate mines are owned by the Government of India and the Siddis have to purchase a lease to dig for the stones. It seems a fair presumption to suggest that in Pre-Independence days these revenues went to the treasury of Rajpipla State.

Once the bagged raw material has reached Cambay it enters a process which will transform the smooth patinated stones into beads and other objects. The first step in the process is to heat the material in small pots filled with smoldering sawdust (Fig. 4). This causes a physical change in the stone which makes the next step, chipping, an easier one. The knapping of the agates is done in two stages, the first of which roughs out the shape of the bead (Fig. 5). This is then smoothed by finer chipping. In both cases the technique involves the use of a hammer and spike, or anvil, driven into the ground. The rough chipping hammer is made of water buffalo horn on a thin flexible bamboo handle. It was made clear to me that the horn must be buffalo and that the horn of cows was completely unsuitable. The work at the chipping stations in Cambay proceeds briskly and a final, roughed-out bead can be produced in no more than two or three minutes. Beads requiring further chipping are moved to another worker who handles this task. I have never observed a case where the same person simply took up a smaller hammer and performed the refined work himself. The small iron hammer (Fig. 6) used in the process is a marked contrast to the bulky horn hammer. It is also interesting to note that all of the chipping is done by males, a fact in agreement with the overwhelming ethnographic record documenting the working of stone in other societies from other parts of the world.

The chipped bead ‘blanks’ are then sorted and sent to be ground to their final shape. This smoothing operation takes place in a separate workshop area, and is, again, a specialized craft. The work force here, however, is composed of both males and females, generally young—evidence that the operation is one requiring little skill. The abrasive wheels against which the beads are ground are commercially made today and powered by electric motors. This is one of the few applications of a mechanical contrivance in the Cambay bead industry. The final polishing operation is also mechanized and will be described later.

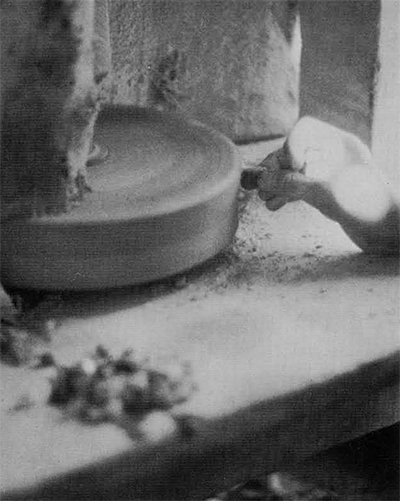

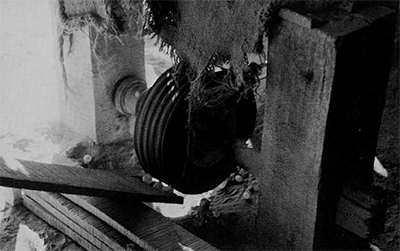

The grinding is accomplished by simply holding the face of the bead to be shaped against the wheel by hand (Fig. 7). Several individuals generally work at a single machine. The grinding of a single bead never takes more than a minute. Spherical beads are shaped on a specially formed ‘corrugated’ grinding wheel as shown in Fig. 8. This wheel is used in conjunction with a simple but specially prepared wooden implement which holds the rough chipped stones in place while they are pressed against the rapidly spinning wheel. It takes only a matter of seconds for rough chipped blanks to be transformed into nearly perfect tiny spheres.

The grinding operation is dispersed throughout Cambay in many different workshops. Some of these are quite large, with twenty or thirty grinding wheels. Other shops are small. Even those with only one grinding wheel exist. I observed no workshop where both the chipping and grinding take place under the same roof, or even using the same personnel.

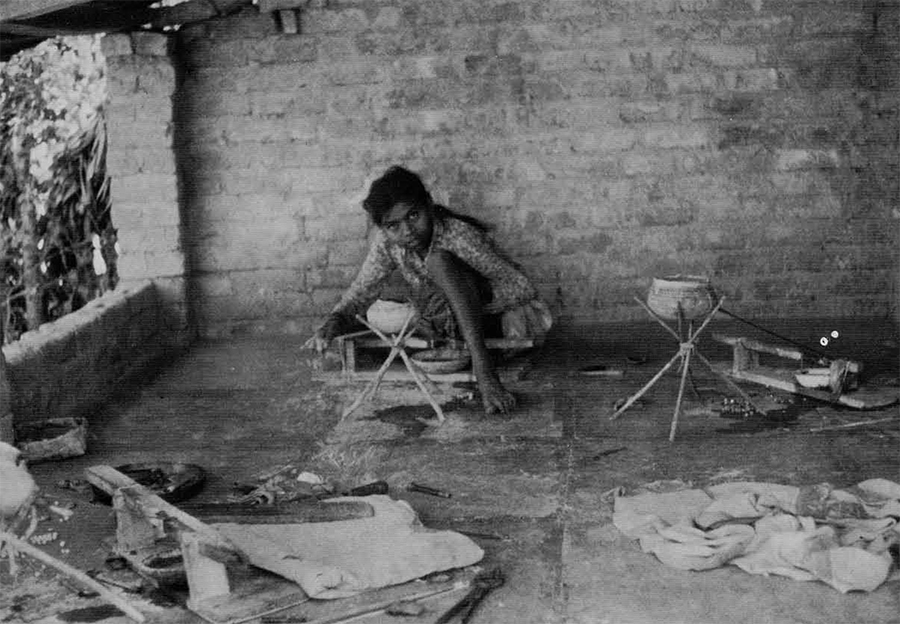

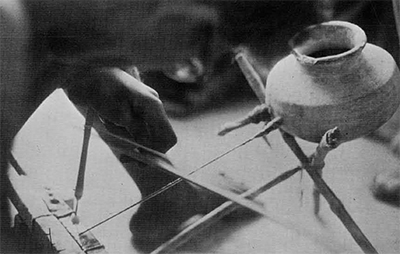

At this point the beads are ready to be drilled. Perforation is accomplished with a diamond-tipped bit set in a wooden shank and propelled by a bow. Rough diamond chips are purchased by individual drillers and set in the drill tip by using an awl to form a cup at the drill point. The diamond chip is then set in this indentation and the edges of the cup are closed around it.

Figs. 9, 10 and 11 show a small drilling operation and the position assumed while the craftsman is actually at work. The small clay pots seen in the photographs hold water and the grit from past drillings. This acts as a lubricant for the cutting operation. The flow of water comes not through a hollow tube but as individual drops down a wire and is regulated by the snugness of fit of the wire’s mount into a small spout, or bung, on the vessel. The grit, which steadily accumulates in this water, is seemingly also an important commodity since its presence in the cutting hole would produce some abrasion and hence further the penetration of the stone.

The drilling position is interesting. The craftsman assumes a seated posture on a small rug on the floor of the shop. He cups a small (ca. 5 by 5 cm.) fragment of hard coconut shell in his right palm. This acts as the top bearing in which the drill shank turns. He then places his right arm under his right leg, turns the string of the bow around the drill shank, places the tip of the drill on the object to be perforated, adjusts the water and begins to work. His leg is positioned over the work in such a way as to allow him to use it to apply a carefully controlled downward force.

The speed at which the beads are drilled is in large part determined by the hardness of the material, and there is some variety here. I have information on the cutting rates for chalcedony, a kind of banded agate. The perforation of a single spherical bead approximately one-half centimeter in diameter takes about twenty seconds, including turning the bead and initiating the cut from the end opposite the starting point. To earn a standard wage for this work a driller must drill 500 to 600 of these small beads per day. Another bead, a large rectangle 4.5 centimeters long with a square cross-section, was perforated in seven minutes. Thus, even with a simple technology the task of drilling is of no great magnitude.

No matter how small the bead, the drilling is always started from one end and completed by drilling a second hole from the opposite side. My impression is that the initial drill hole is always taken to a point somewhat beyond center so that the second hole is not as deep as the first. I interpret this procedure as a safer course of action than drilling straight through the bead, which might cause breakage and shatter around the exit hole. The precision with which the second hole is placed, and the way in which the two holes meet, are important criteria for grading the final bead. Those necklaces strung with improperly or carelessly drilled beads were described to me as looking ‘lumpy,’ with the individual elements at unattractive odd angles.

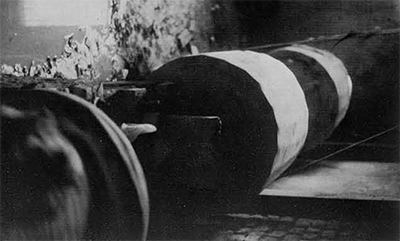

The next step in this process of bead manufacture is the final polishing. There are only two shops in Cambay that do this today and both proprietors are very secretive about the process. However, the outlines are clear, and are essentially the same as those used by rock hounds in America. The beads are placed in a drum with an abrasive slurry (Fig. 12), and continuously turned until their surfaces have been smoothed and polished. This takes approximately a week. The Cambay process involves a first turning in slurry with a coarse abrasive, and a second session with a finer powder. The drums are wooden vessels containing 100 kilogram loads, and are propelled by electric motors.

Prior to the use of electricity and more elaborate mechanical contrivances, the polishing was done by hand. That is, beads and slurry were sewn into a skin bag and this was ‘rolled’ across a floor between two men. This method, while certainly not very interesting work for the labor, seems to have been every bit as effective as the one now used. It is also a good example of the way in which mechanization of beadmaking has really not altered the principles by which the task is accomplished.

Finally, polished beads are sorted by quality and enter the commercial market either as bulk packets of unstrung objects or as necklaces.

There is certainly much more to be learned about beadmaking in Cambay, and this article is a mere outline of the basic principles of the industry. But, nevertheless, I hope it has given an indication of how a simple technology can be used to mass-produce a commodity which has reached millions of people all over the world for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.