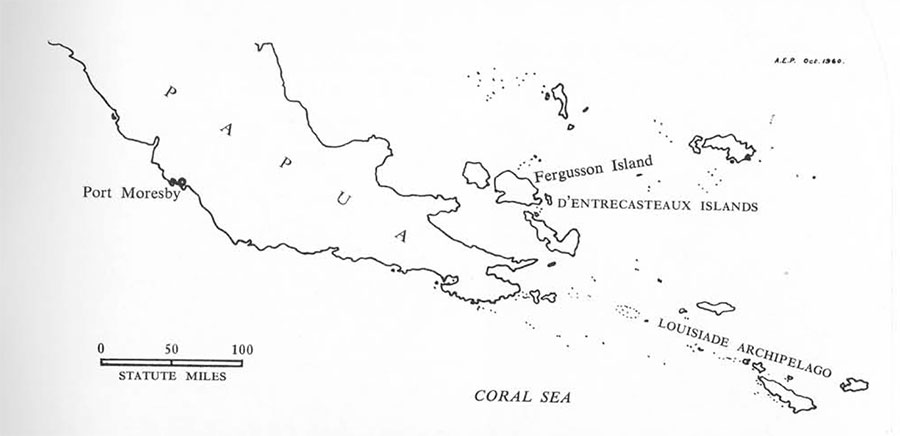

At dusk on May 12, 1958, as I sat on the beach talking with my adoptive family, four beautifully decorated canoes rounded the point east of us and drew up outside my house. I recognized them as a group just completed in Paiaiana, the Molima census group east of Ailuluai, in which I lived. The crews had stopped to invite me on their maiden voyage, and I was delighted to accept. Because the brief calm season was drawing to a close, this might be my only chance to see the final ceremonies associated with the construction of a new canoe. While the wind blows, the Molima coast is dangerous even for European vessels, and the easily swamped native canoes do not venture out. I quickly packed my gear and then, when I found that the Paiaiana men had settled down to chat and chew betelnut with my household, reviewed my notes on canoes in preparation for the activities of the next few days.

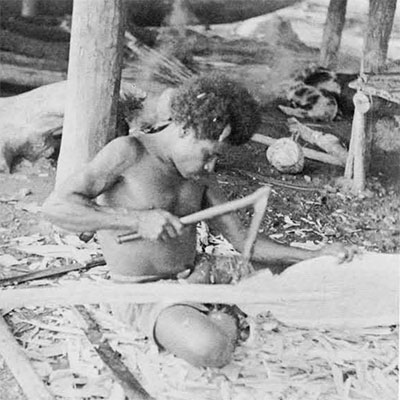

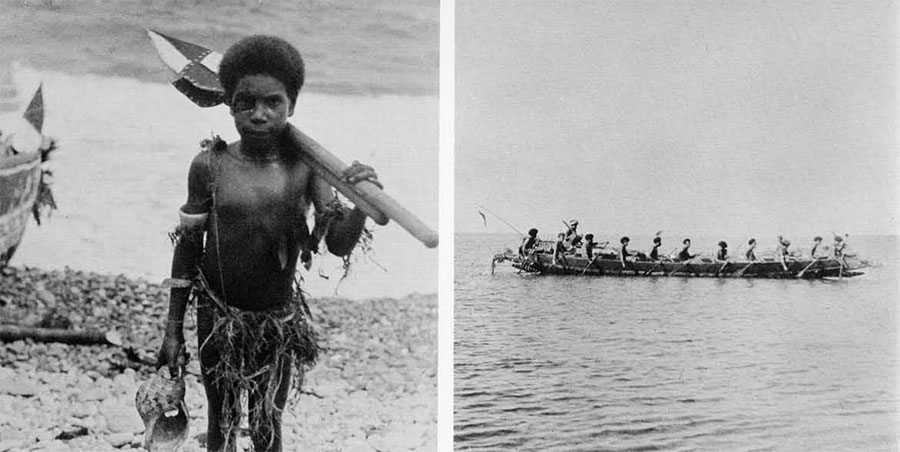

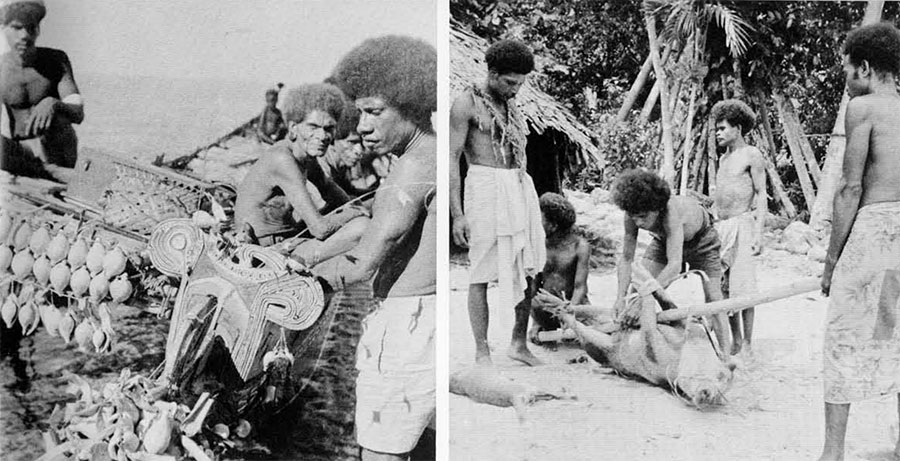

From the day I arrived in Molima, I had been fascinated by the large outrigger canoes. They were composed of planks sewn to a dugout hull, and each one carried end-boards delicately carved in traditional curvilinear designs, surmounted by a small human figure. The newer ones were painted orange, black, and white, and further decorated with ornamental braiding, cowrie shells, and fluted strips of pandanus leaf. Few hamlets contained such canoes, and I found that they were always owned by important men in the community. The reasons were complex. A plank canoe is not only a principal form of wealth, but also a means of acquiring high status for the man who sponsors its manufacture. Unless he can fill the role himself, he must hire an expert canoe-maker, a descendant of other experts who knows how to shape and assemble the parts and how to perform the proper magic at each stage. A second craftsman may be needed to carve the decorative portions. Their services are expensive, and only a fairly wealthy man can afford them. He must also be able to call upon and direct the efforts of kinsmen and fellow villagers in heavy work such as the collection and transport of materials, and must provide a series of feasts to reward them. They are usually willing to help, both because of the food and because they will be able to use the completed canoe, but it is no small task to assemble them in sufficient numbers when they are needed. When the canoe is finished, the owner must organize a splendid ceremony to mark its first appearance, and it must be judged both seaworthy and beautiful. Finally, he must take or send it on its maiden voyage, and hope that the villages it visits will show approval of the canoe and its owner by donating quantities of food and valuables.

Canoe-making is consequently a major task, not to be undertaken lightly. Each one is built in the name of a dead kinsman of the owner, and the latter acquires additional prestige by giving a mortuary feast with the foor obtained on the maiden voyage. After that, the owner uses the vessel to visit friendly tribes, on Fergusson and other islands, with whom he trades for necessities such as clay pots and wealth tokens such as shell ornaments. An important many must be wealthy, and the most successful trader in a community is likely to become its headman. In the past, canoes were also used for raids on enemy tribes, in order to capture victims for cannibalistic feats. Now that the Australian government has eradicated warfare and cannibalism in this area, the trade network has enlarged to include not only former enemies but groups living outside the region into which the Molima dared to travel aboriginally. The leader who was once expected to show equal prowess in war and trade now proves himself in trade alone, but has increased opportunity to do so. His path to prestige is still greatly facilitated by possession of a canoe, and the Molima say that mountain dwellers never become as important headmen as coastal dwellers because they lack canoes.

If a man decides to make a canoe, he may begin at any time, and often spends a year or more in intermittent work, but the final phases should always occur in the calm season. I had watched several stages of manufacture, but because of an ill-timed trip to the interior of the island, had missed the launching of the four Paiaiana canoes. My notes were based on descriptions by the participants, who never tired of telling me what a pity it was that I had not seen one of the two most important Molima ceremonies. (Later I saw a version that was severely curtailed because of the stormy seas.) When the ceremony began, each canoe was still hidden in its shed, along with men and women of the owner’s village dressed in full dance regalia. While these sang magical songs to make the canoe swift and well-balanced, men from other villages paddled their canoes toward the shed. Each canoe carried a performer who danced back and forth on the platform, slinging missiles at the shed during the pauses in the dance. Meanwhile, the group inside finished singing and the men began to drum. At the sound of the drums, a man stationed outside recited a spell to increase the splendor of the appearance of the canoe and the dancers, and opened the door. The canoe, hidden by mats and accompanies by drumming men and dancing women, was drawn out and then revealed in its full glory. The boys of the owner’s village performed spectacular solos, of a type otherwise reserved for major mortuary ceremonies; then a man and two girls danced in succession on the canoe platform. When they had finished, the canoe was launched, apparently empty, and then paddled back to shore by small boys hidden inside. Then the men of the owner’s village showed it off by paddling it far out to sea. When they returned, girls escorted the canoe ashore, sprinkling it with sea water from their cassowary feather dance ornaments.

These formalities over, the visitors had a chance to try out the canoe. They raced it against others, slung fruit from it as warriors had slung stones during sea battles in the past, and tried to tip it over. If it capsized, the crew had the privilege of raiding the owner’s house and fruit trees. One of the Paiaiana canoes was tipped over twice during the trials. Finally the visitors came ashore, pelted with vegetables and betelnut by women of the village, and were feasted by the canoe owner as a reward for having attended his ceremony.

The owners of the four canoes that had been completed at the same time then began to prepare for the maiden voyage. This always consists of visits to other coastal Molima villages and the villages of the two adjacent tribes who were Molima allies in the past, the Kukuya to the west and the Nade to the east. At each village the canoe owner is given a raw animal and vegetable food to take home for the mortuary feast. Important men in the group also receive individual presents of valuables, awarded according to their prestige or the strength of their magic, or in payment of former debts. Gifts of food are repaid in kind when residents of the host village make a new canoe and take it on its maiden voyage, while debts of valuables are repaid at any convenient time. In past weeks, I had twice been a member of a host group, but this was my first opportunity to fill in the picture from the point of view of the visitors. This first part of the trip would cover the area west of Paiaiana, starting with Kukuya and then working back through Molima, and a shorter second trip would cover Nade.

By 9:00 P.M., the crews were ready to leave, and I climbed onto an outrigger platform and dozed there as the men paddled toward Kukuya. At midnight we landed on a stony beach out of earshot of the nearest Kukuya village, and settled down for the night. I was awakened before dawn by chanting, and got up to find magical performances under way. Beside each canoe, a magician recited spells and spat to transfer the power of the words to the vessel. The spells were intended to enhance its beauty so that the Kukuya would express their admiration in generosity to the owner. At the same time, members of the crew were adorning themselves and reciting private spells to attract personal gifts. Once the magic had been performed, no one could eat until meat was given by our hosts. The men chewed betelnut and smoked cigarettes in lieu of breakfast, and we embarked shortly after dawn. As we paddled toward Lapwalapwa, the village selected for the beginning of the display, the men blew charmed conch shell trumpets to announce our coming.

Arrival struck me as anticlimatic. We beached the canoes, completely ignored by everyone except a group of children who watched from a distance. A canoe owner asked for the village headman, and eventually someone replied that he was coming. We stood at the edge of the village to wait for him; it would be a breach of etiquette for us to sit down at that point. Finally his deputy arrived, greeted us, and led us to the stone-paved circular platform which is the village gathering-place throughout these islands. We were told that the women would cook food for us while the men assembled; early as it was, some had already left for the gardens. Then the headman arrived, and the speechmaking began, sometimes in Kukuya and sometimes in Molima. My Kukuya was limited to the equivalent of “Hello,” so that I could not follow all of the interchange, but the gist was clear. The headman jokingly threatened to withhold food, saying that he had waited all day to be fed when he visited Paiaiana. The leaders of our group responded in kind, and then we simply waited for almost two hours, until the giftgiving suddenly began. The young men did not participate, but stayed on the beach cooking food which the village women had brought them. The older men sat on the platform facing inward, displaying great nonchalance as Kukuya men and women, one by one, approached a visitor, made a short speech, often in angry tones, and laid or flung a gift beside him. The recipient usually neither looked down nor replied. The gifts were an interesting mixture of traditional items of trade, goods of European manufacture, and articles made by natives in distant parts of New Guinea and acquired by Fergusson Islanders when they went to work on plantations. Those given that day included clay pots, a stone adze blade, a shell bracelet, the pendants of shell and boar’s tusk which are the badge of a headman, a cotton shirt, enameled basins, a Chinese wooden chest, and a painted barkcloth breechclout and two net bags from New Guinea. Some gifts were described in the speeches as “cooked,” meaning that they were the settlement of old debts, and some as “raw,” new debts for the recipient.

Trading was suspended in the middle of the day while we waited for two pigs, both repayments of old debts, to be captured. Our group sat chewing betelnut, supplied by our hosts, complaining of lack of sleep, and drowsing. When our meal was finally cooked, one of the young Paiaiana men came up to me and said, “Will you eat dog intestines?” I knew that dogs formed a major part of the gifts of food, but I had not realized that they were the only source of meat for the travelers. Unlike pigs, which are taken back alive, dogs are killed before they are given, and although some are smoked for the mortuary feast, the rest are eaten at once. Deciding that dog was preferable to numerous meals consisting wholly of boiled vegetables, I raised my eyebrows in assent, and was given a dish of liver, indistinguishable in taste from any other liver. At subsequent meals I found other cuts of dog easy to eat, though not particularly tasty.

When we had eaten, our hosts brought the major gifts of food: pigs, more dogs, freshly dug yams, and plantains. While the young men loaded the canoes, carefully covering the pigs and pots against the sun, and smoked the dog meat, the older men stayed on the platform to receive a few final gifts and exchange speeches with our host. The speeches contained numerous references to the following of ancestral custom, the proper behavior of important men, and the obligations of kinship which had been established by intermarriage between the two tribes. Men tended to point out how well they themselves were behaving rather than to praise others. This ended the business of the day, and we ate supper and went to bed by ourselves, again ignored by the people of Lapwalapwa. It seems clear that these trips are primarily a formal method of maintaining peaceful relations between separate villages and tribes, so that they can cooperate in trade, warfare, and ritual, but are not expressions of genuine friendship. The warmth which the Molima show in dealing with close friends and near kin is notable lacking, and even the joking tends to be aggressive. If a new canoe visits a village under a special tabu designed to preserve foodstuffs for a large mortuary feast, the hosts may berate and even strike the visitors, who in turn despoil the village trees. Serious anger is not being expressed, since a village can preserve its tabu by simply refusing to receive the canoe. Nevertheless, this behavior illustrates a fact which the Molima explicitly recognize: relations between different districts, even within the same tribe, are basically unfriendly if not actually hostile, and considerable effort is needed to preserve alliances between such districts.

We set out early the next morning, after further recitations of spells, and began our slow journey back toward Paiaiana. Two men paddled each canoe, and the others walked along the beach to see whether the villages we approached would receive us. I stayed with the canoes, and for long periods we waited offshore for the walkers to arrive and negotiate. By contrast, the periods spent in the villages were relatively brief. The few villages under tabus all rejected us, but in the others we received more and more food and valuables. We spent our second night outside a Molima village, and by noon on the third day had arrived at my hamlet, at which the men dropped me off. I did not accompany them on the brief trip to Nade, but was invited to the mortuary feasts held immediately thereafter in the four hamlets of the canoe owners. By virtue of my participation in the trip, I was entitled to a share of the food.

I arrived in the first hamlet early in the afternoon, while the women were still cooking the food. The men were sorting the valuables that they had acquired, pairing each bracelet and necklace with another of exactly the same size, so t hat debts would be repaid with perfect accuracy. The Molima prefer this scrupulous exchange to the sharp practice of neighboring tribes, such as the Dobuans, who try to obtain goods by false promises.

When the food was ready, a deputy of the canoe owner began to distribute the pots. Important men in Molima are inclined to leave such tasks to others. With the name of reach recipient, the deputy mentioned his contribution, if any, to the making or display of the canoe. Part of the food was given to the helpers, and the rest to the matrilineal kin of the dead man in whose name the canoe was made. The latter, in return, lifted the food tabus which the other kin of the dead, including the canoe owner, had been observing as a sign of mourning. Because I was moving from hamlet to hamlet that day, I saw the rite only once. It was typically Molima in its simplicity: a woman of the matrilineal kin walked through the hamlet and waved a cooked yam in front of the people sitting there. They apparently paid no attention, but in fact knew that they could now eat freely of all foods. This seemingly casual act was the final step in a long and elaborate series of exchanges between the matrilineal and the other kin of the dead. These exchanges begin at the funeral and continue for years through several mortuary feasts, at which the matrilineal kin, who do not mourn but perform duties such as burying the corpse, gradually release the other kin from mourning restrictions in exchange for being feasted.

By constructing a canoe and taking it to visit other villages, a man not only honors his dead kinsman but enhances his own reputation, since the resulting feast is vastly superior to an ordinary one. Afterwards he can continue to demonstrate his superior qualities as both a leader and a family man, because he now owns a canoe which serves the whole community and will eventually be inherited by his son, who can use it to emulate his father. As long as the Molima retain their traditional system of values, plank canoes will continue to be an important feature of their culture.