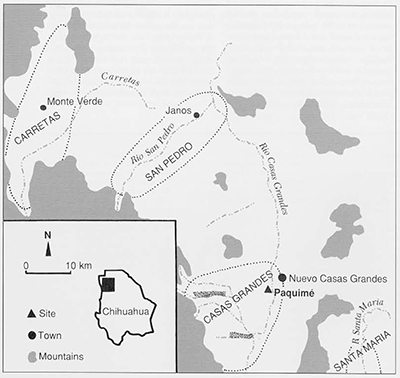

- This aerial view of Casa Grandes was taken during excavation in the late 1950s. the mounds in the foreground are unexcavated, decomposed adobe-walled suites of rooms, some at least tree stories tall. upon excavation, the wall stubs (background) revealed a complicated pattern of rooms. The round sunken structure in the far background is a water reservoir, and a large I-shaped ballcourt is located in the extreme upper righthand corner of this photograph.

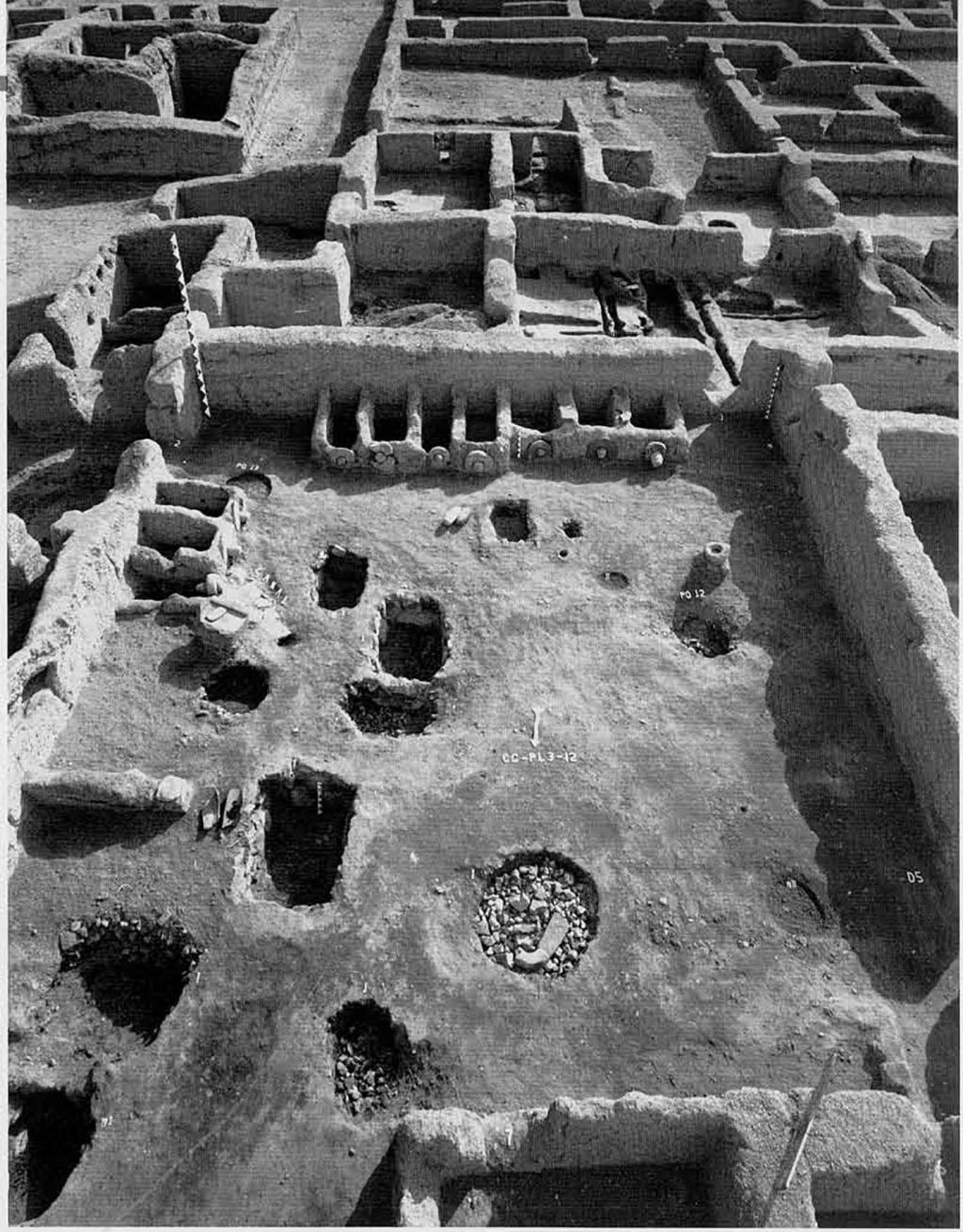

- In order to understand prehistoric changes through time, the Joint Casas Grandes Project also excavated sites dating to earlier and later than the Medio Period (A.D. 1150/1250 to 1350/1450), the time of Paquimé’s greatest power and influence. The Project’s leader, Charles Di Peso, excavated the Spanish church of San Antonio de Padua de Casas Grandes, located a little over 5 kilometers north of Paquimé. The ruins of the church can be seen here overlooking the Rió Casas Grandes valley bottom. While test excavating in front of the church, which was used for 25 years during the later half of the 17th century, the research team unexpectedly located a small pithouse village predating the Medio Period. The excavated village can be seen at the left of photograph.

- The two large I-shaped ballcourts at Paquimé are similar to those from Mesoamerica to the south where ritually significant games were played. Although the form of the structures is similar to Mesoamerican ballcourts, it is not certain that the same games were played at Casas Grandes. Other ball courts with different shapes are found to the northwest, among the prehistoric Hohokam of central and southern Arizona.

- The Arroyo la Tinaja site. This is one of the largest sites near Paquimé. Note the three mounds of eroded adobe roomblocks, the two stone circles, and the I-shaped ballcourt.

- Most Casas Grandes sites are mounds of eroded adobe walls and roofs. This rubble mound is typical and may have once been a house containing around 10 rooms. The level of looting is also typical.

- Many Casas Grandes related cliff dwellings are known from the Sierra Madre mountains just west of Casas Grandes. Cuarenta Casas (Forty Houses), shown here, is a well-known example located southwest of Paquimé.

“the great difficulty being in determining where the remains of these people [of Cases Grander] ceased, and those of ruder and probably hostile though kindred tribes began.”

Blackiston 1908:282

The spectacular ruins of Casas Grandes in northern Mexico (see map on inside front cover) stand in stark contrast to the common image of the prehistoric Southwest as a place where small kin groups lived in pastoral settings, unfettered by the trappings of “civilization,” all generations part of an endless, unchanging, and millennia-long cultural tradition. Casas Grandes (Spanish for “great houses”; also known as Paquimé) was one of the largest and most influential communities of its day in the North Amelican Southwest, It covered 36 hectares and had over 2000 rooms, many ritual structures, a sophisticated municipal water system, an accumulation of extravagant wealth, and evidence of the mass production of goods (Fig. 2).

Southwestern prehistory is rarely associated with large-scale societies incorporating class differences, tribute payment, cities, monumental public works, and the integration of many communities over a wide region. It is true that the prehistoric societies of the Southwest were never as large as those in the neighboring areas of Mesoamerica to the south or the Mississippian cultures of eastern North America. Yet, archaeological research over the past two decades has clearly shown that at various times and in different places regional cultural networks linking many communities did emerge in the Southwest, although their nature is currently a source of profound debate among archaeologists. One clear example of a complex Southwestern society is Casas Glandes in northwestern Chihuahua. (Fig. 1).

Our research focuses on understanding the regional character of Casas Grandes society. In the absence of efficient prehistoric transportation, that is, watercourses or beasts of burden, was the community of Faquim able to control a large area or was its influence less direct? Did the relationships between communities in the region change with the well-documented fluctuations in precipitation that affected other prehistoric Southwesterners? How closely was the development of Casas Grandes tied to the formation of other Southwestern regional systems, such as Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico or the Classic Period Hohokam of central and southern Arizona? Although our initial six-week survey project could only begin to address these and other issues, we did conclude that the core or nucleus of the Paquimé system was remarkably small, with a diameter on the order of only 30 kilometers around the site.

Casas Grandes has not received the attention it deserves, largely because it is neither in Mesoamerica nor in the northern Southwest. For most Mexican archaeologists, the prehistoric sites of the far northern states have riot had the lure of the great prehistoric cultures of Mesoamerica and Central America. And Few North American archaeologists look south of the border, a modern demarcation of no prehistoric significance. To most, the center of the prehistoric Southwest is the Four Corners of the Colorado Plateau, where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado meet. Here, the spectacular and well-preserved Anasazi cliff dwellings and surface pueblos, such as those at Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, have justifiably received attention for well over a century from both professional archaeologists and tourists alike. The images of the prehistoric North American Southwest so clearly engraved in our minds come from this area. However, this perception masks the reality that most of the ‘Southwest” is south of the Four Corners. In fact, the center of the prehistoric area we now call the Southwest probably lies closer to an ‘International Four Corners,’ the region where the states of Sonora, Arizona, Chihuahua, and New Mexico come together.

Paquimé: The Center

An appreciation of the regional nature of the Paquimé system must begin with a view of its center. Since Baltasar de Obregon first described it over four hundred years ago, scholars and travelers have recognized the significance of this site. Paquirné’s importance was finally documented through excavation in 1959-1961, when the late Charles C. Di Peso, Director of the Amerind Foundation in Dragoon, Arizona, marshalled the foundation’s resources and collaborators to complete the Joint Casas Crandes Project (JCGP), an expedition conducted with the Institute Nacional de Antropologia e Historia in Mexico. While only a portion of the site could he excavated, the project’s eight-volume summary report (Di Peso 1974; Di Peso, Rinaldo, and Fenner 1974) clearly illustrates the complex nature of the community: class differences, specialized economic production, enormous wealth accumulation, and monumental architecture.

The city of Paquimé was the culmination of a long archaeological sequence that began with the earliest gatherer-hunters 12,000 years ago (Fig. 3). The region’s prehistory followed a pattern common to much of the Southwest and Far northern Mexico. The first Farming communities developed around A.D. 200, and up until Casas Crandes’ florescence during the Medio period, most people lived in small, mostly self-contained villages, conducting limited trade with other communities. The Medio period, which probably began sometime during the latter part of the 12th century (A.D. 1150/1250) and ended between A.D. 1350 and 1450, was a time of obvious wealth, development of large communities within a regional network, and probably increased conflict. The Following Tardier period was a time of substantial population reorganization and movement that only intensified with Spanish contact and colonization in the 1660s.

Paquimé is located at the headwaters of the Rio Camas Grandes where tributaries emerge from the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains. Here the agrarian Paquimnans and their ancestors Found a floodplain nearly a kilometer wide, with rich soil and abundant water. The growth and influence of Paquimé was not, however, due solely to its excellent farming potential. There is clear evidence of specialized economic production during the Medio period that presumably was largely responsible for the accumulation of wealth.

Two items of exchange, macaw parrots and shell, were especially critical for Paquimé. Di Peso found the remains of macaw breeding at Paquimé, including many nesting boxes and macaw skeletons (Fig. 4). As many macaw skeletons were recovered From this one site as had been found to that point in all the hundreds of other sites excavated in the Southwest. The macaw was a necessary item for rituals for many prehistoric groups in the North American Southwest, and there is little question that Paquime was the source for the macaw trade and probably controlled macaw production and distribution. The discovery of nearly Four million shell artifacts in a few storerooms at Paquimé provided all the evidence needed to show that shell trade was also an integral part of Casas Grandes commerce, especially in light of the fact that the site is situated hundreds of kilometers from any coast (Fig. 5).

While exotic artifacts such as macaws and shell have received the greatest attention, there is evidence that specialized economic production of more mundane goods flourished at Paquime as well. The century plant and turkeys are two examples. Since the number of turkey skeletons and turkey pens found is nearly equal to that of macaws, turkey breeding may have been on the same scale as macaw production. And like macaws, turkeys seem to have been raised for ritual use: none of the hundreds of turkey skeletons found had been butchered for food.

Similarly, processing of the century plant (Agave) was also carried out on a large scale. This succulent, with its conspicuous flowering stalk and dense rosette of spine-tipped leaves, is native to the deserts and mountains of the North American Southwest, and its fibers and baked hearts were widely used by native Southwesterners. The roasting pits at Casas Grandes are by Far the largest known, and their extreme size suggests that massive quantities of agave, beyond those normally consumed by a family, were being cooked. This conclusions is consistent with the fact that the roasting ovens are restricted to two areas within Paquimé and are not spread out across the community as might be expected with a more widely practiced activity.

Casas Crandes society had elites, as is evidenced by the intriguing presence of a few burials entombed in two small chambers within the Mound of the Offerings, at the northwest end of the site. Unlike the hundreds of other burials excavated, these were afforded the special treatment of being placed inside ceramic vessels within special tombs. Further evidence of class differences came from a few rooms that yielded enormous amounts of exotic goods. Millions of shell artifacts, rare ceramics, and other unusual artifacts were excavated from these rooms. The restricted distribution of such wealth is best explained by tight control of the economy by a relatively small group.

Additional evidence that Paquimé was something other than an egalitarian village came to light with JCGP research. The massive and integrated architecture of Casas Grandes hints at planned and coordinated labor. Furthermore, a sophisticated system of canals brought water From a spring to the site where it was emptied into a settling tank and then into a main reservoir. A series of smaller canals distributed water to the suites of rooms, and an additional system of drains removed excess water From the community.

Paquimans practiced a rich ritual life. The presence of public “monumental” ritual architecture has been used to infer patterns of social integration among prehistoric peoples. The large number of such structures at Paquime suggests that this community was also a religious center. The western portion of the site housed many mounds in zoomorphic or geometric shapes. While none is especially large or required massive labor to construct, the diversity of shapes is not matched at any other site in the North American Southwest. The Mound of the Offerings, which contained the special burial crypts mentioned above, also had a room with unusual symbolic items, such as a T-shaped stone altar, and was located next to a ceremonial plaza with a series of roofless rooms.

Ballcourts were used For a religious ballgame among Mesoamerican groups, and three ballcourts, two of which were I-shaped and similar to those in Mesoamerican, have been excavated at Casas Grandes (Fig. 6). Ballcourts are also found among Hohokam sites in central and southern Arizona; however, the Hohokam ballcouits are not I-shaped. We do not know if Paquime ballcourts were used like Hohokam ones or if in fact the Paquimans actually performed a Mesoamerican ritual game in their ballcourts.

Paquimans Hinterland: Recent Survey Data

Few question that Paquimé was the heart of a complex society with specialized economic production and the presence of elites and wealth, but what were its relationships with outlying communities? We know that there were hundreds of communities in the International Four Corners area contemporary with Casas Grandes that had similar architecture and pottery types. Did Casas Grandes maintain an hegemony over outlying regions, or did it control only a small area? Previous archaeological reconnaissance surveys in northwestern Chihuahua conduced in the 1920s and 1930s provided insufficient data to address such questions. Furthermore, the large amount of archaeological work undertaken in the United States in the past quarter century has failed to deal adequately with Casas Grandes’ regional relationships. Part of the reason for this is, of course, that any sites in the United States would have been at least 130 kilometers from the center at Casas Crandes and thus might well have had the weakest relations with the Paquimé .

One must work closer to Paquimé, in Chihuahua, in order to study sites that most likely had the strongest connections with Casas Grandes. The little research available for northwestern Chihuahua provides tantalizing clues about the regional system. Prehistoric trails have been noted informally. Although they have not been mapped or studied, their presence points to some ongoing relationships between communities. More interesting are atalayas, stone structures found on the summits of hills and along ridge tops. Based on information in early Spanish accounts, these structures have been interpreted as parts of a fire communication network that would have linked together villages many kilometers distant. We expect that there was a regional nature to the Paquimans polity, and there is some evidence to suggest that it might have been wide-ranging.

The primary purpose of our survey project was to provide more up-to-date archaeological data on the regional character of the Paquiman polity. Given the possible size of the Paquimé system, we believed that our initial survey should cover a broad area that is, we could not restrict our survey to a small drainage and then extrapolate these patterns to the entire system. On the other hand, we had very limited funding, enough for a modest six weeks of survey. Therefore, we conducted a targeted reconnaissance survey of larger, known sites in northwestern Chihuahua (Fig. 1). We searched out important sites, recorded and mapped them, and collected a sample of surface artifacts, such as pottery sherds, chipped stone debris, and grinding stone fragments. With this approach, our analyses could look for the broadest regional patterning. We were also able to conduct systematic surveys in two areas. Survey crew members spaced 20 meters apart walked back and forth for complete ground surface coverage. By using both data-gathering techniques, we increased our ability to interpret the survey data. The survey data were divided into four analytic clusters centered on drainage areas: Casas Grandes, Rio San Pedro, Carretas Basin, and Rio Santa Maria.

We recorded a total of 87 sites. Despite the fact that severe looting of ancient pottery for illegal sale on the international antiquities market had taken place, we were able to record much information on site location, site size, architectural variety, and the types and abundance of surface artifacts, mostly ceramics, chipped stone, and ground stone (Figs. 8, 9). These data reveal important trends that provide insights into the Paquime polity.

A Population Explosion

The population of Medico period sites is much greater than in the preMedio period. Even though our project focused explicitly on the Medico period, we did record sites of other periods in our count of 87. The low number of pre-Medio period sites is striking. No such sites were located on systematic survey, and we recorded only three on the targeted reconnaissance survey. With the current data we cannot precisely estimate the magnitude of the population explosion or discern the reasons for it (local increase, immigration, or both).

We do not understand how Casas Grandes’ power may have affected or been affected by changing demography. However, there seem to be a number of large sites scattered throughout northwestern Chihuahua. These sites are intermediate in size between Paquimé, by far the largest in the region, and the hundreds of hamlets. Large-scale societies often have a hierarchy of administrative authority, with regional or secondary centers acting as agents for the center over the outlying areas. The large sites we recorded may well have played this role within the Paquiman polity.

The Casas Grandes Core

There are clear regional differences among Medio period sites within northwestern Chihuahua. Specifically, sites within 30 kilometers of Paquimé, especially to the west and southwest, are different from those farther away. Several lines of evidence independently point toward this conclusion.

Our surveys yielded surface evidence of macaw production. Circular stones with a central hole were found in place at Paquimé as entrances for macaw pens (see Fig. 4). We recorded similar stones at five sites, all within 30 kilometers of Casas Grandes. However, we found no surface evidence of these artifacts at sites farther than 30 kilometers from Casas Grandes in our study area. Thus, the present evidence suggests that macaw breeding occurred at a number of sites integrated within the Paquimé-dominated system, but only at those a short distance from the center.

The presence of public ritual architecture has been an imperfect but nonetheless important clue to the character of regional systems throughout the world. None of our outlying sites showed evidence of the ritual mounds present at Paquimé, again emphasizing the unique nature of this site. However, we did find numerous I-shaped ball-courts, ballcourt-like structures, and stone circles. Two features were clearly classic H-shaped ballcourts (Fig. 7), and the others, which we will call ball-courts features (Fig. 10), were composed of an especially flat area with two parallel rows of rock lining their long axis and often with slight earthen berms at the ends. All ballcourts and ballcourt-like structures were approximately the same size. We recorded four ballcourts or bahlcourt-like structures along the 9-kilometer Arroyo la Tinaja systematic survey area. Two more were present in the El Alamito systematic survey area. While at least one site each in the Caritas Basin and in Hidalgo County, New Mexico, just to the north, had a bailcourt, there appears to be a greater concentration of balcourts and ballcourt-like features within a 30-kilometer radius of Paquimé.

In addition to ballcourts, “stone circles” may be evidence of ritual practices (Fig. 11). These features are circles of stones usually 6 to 12 meters in diameter. We do not believe that they are roasting ovens, even though they appear to be quite similar on the surface. They are often located near ballcourts. While we do not know their function, the features are quite common at sites within 30 kilometers of Paquimé but are absent at more distant sites. Sixteen were recorded in the two systematic survey areas, and many others were noted during the reconnaissance survey.

Sites closer to Casas Grandes tend to be different in other ways also. The largest sites within 30 kilometers of the center have greater architectural diversity and more eroded adobe mounds than those farther away. Further, this area has a much higher than expected number of the largest mounds. Without excavation, it is impossible to evaluate the reasons for this pattern, but we suspect a different occupation history for communities close to Casas Grandes.

Conclusions

Our short project began as an attempt to discover basic regional patterns that would help us to formulate an initial understanding of the Paquimé centered regional system. We would argue that, compared with other regional networks in the Southwest, such as Hohokam, Chaco, and Mesa Verde, Paquimé provides the clearest evidence of a strongly centralized polity with accumulation of wealth, status differences, and specialized economic production. Its splendor must have shone far beyond its borders. And there is no denying that through economic interaction it must have influenced groups throughout the southern Southwest. Yet it comes as a surprise, to us at least, that the core or nucleus of the regional system appears to have encompassed a relatively small area within 30 kilometers of Paquimé.

We have only begun to understand some basic characteristics of the Paquiman polity and the prehistory of northwestern Chihuahua. Within this 200-300 year period, the dating and historic dynamics of this regional system remain largely unknown. For example, are the large sites near Paquimé early population centers on the same scale as Casas Grandes, with Paquimé gaining dominance through time? Or were these sites always large communities and always subordinate to Casas Grandes? Clearly, only excavation will provide the datable material and the information necessary to evaluate such detailed interpretations. We can end here by going back to Blackiston who stated over eighty years ago that “even at the present day the extent and boundaries of the civilization of the inhabitants of the Casas Grandes of northern Mexico has not been fully determined.