(Museum Object Number: E 10511; height 21.2 cm. ).

This stand, although not from a cult center, closely resembles the religious stands in use in Egypt at this period, while its inclusion within the context of a tomb may imply a ritual significance.

Cylindrical stands for pottery were used by several ancient cultures in the eastern Mediterranean, but their development among the Minoan of Bronze Age Crete was especially elaborate and interesting. By the latter part of the Late Bronze Age, Minoan stands were ornamented with snakes, horns, birds, multiple handles, and other attributes, going well beyond the stage of the simple household pot stand. New evidence for the origins of these stands has recently come from excavations at Kommos, a seaport on the southern coast of Crete, which suggests a fresh look at this unique group of objects.

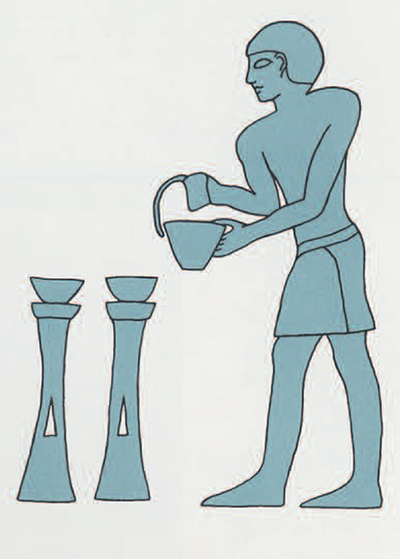

Illustrations on temple walls in Egypt show stands as focal points for the performance of specific religious rituals before the gods: libation, tensing, and the placement of offerings. These rituals often use a vessel on a stand, or held in the hand near a stand. On some representations one can even see vegetables or plants in the stand itself.

Among the ancient Near Eastern cultures using stands, Egypt is a particularly valuable source of information. Archaeological excavations there have yielded a great variety of stands in association with the vessels they were intended to support. Stands are also illustrated both in well-preserved tomb paintings and reliefs (Fig. 1) which accurately record the details of daily life, and on temple walls which depict religious rituals. Because Egyptian pots were typically round-bottomed and made of porous clay, stands were usually included in the design in order to stabilize the pot and make it accessible for use. They appear to have had many uses in both domestic and religious contexts because they could be moved around for storage, and they could also be used to support items other than vessels, such as mats, baskets, and table tops.

Through Egyptian history the stands used in religious contexts conform to specialized types.

(Museum Object Number: MS 4661; height 22.3 cm.).

(Museum Object Number: MS 4681; height ca. 37 cm.).

In the Old and Middle Kingdom tombs, they are usually tall and cylindrical. By the New Kingdom most examples have a tapering shape crowned by a flaring rim. A good example of the New Kingdom type comes from the University Museum excavations at Buhen (Fig. 2). Dating from the 18th Dynasty, it is made of red clay, with a burnished surface. Its shape is similar to a special type of stand found in the tomb chapels at Amarna. These Amarna examples differed from the usual ones in that they were whitewashed on the surface.

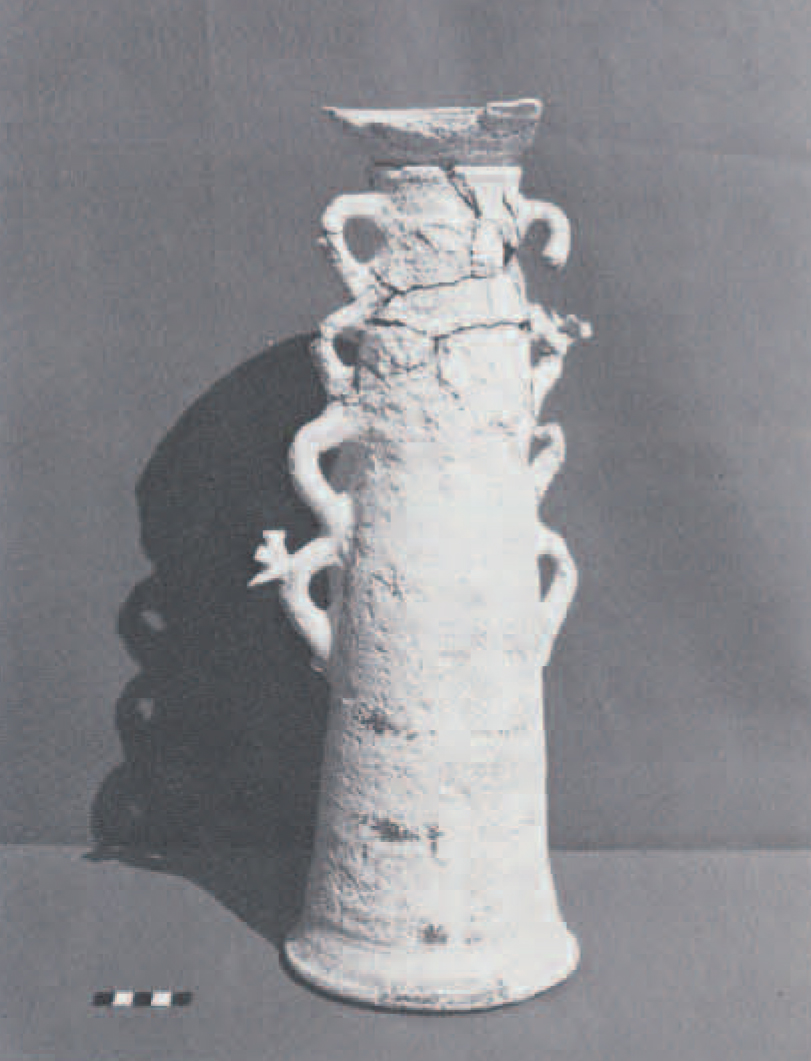

Pot stands were also used in cultic practices in other parts of the Near East. From Chalcolithic times on, Syrian and Palestinian incense burners occur both as single pieces (a stand topped by a bowl) and as two pieces clearly intended to be used together. Some of the stands are fenestrated. They may be one of the antecedents of the early Iron Age fenestrated pedestals from Beth Shan which, curiously, bear plastic decoration resembling elements drawn from the Aegean repertoire but with a somewhat different feeling (see Fig. 10).

In the Aegean, stands are uncommon until the Late Bronze Age. The most interesting series comes from Crete where both plain and elaborate examples have been found at many sites. Coarse undecorated tubular stands probably served many domestic purposes (Figs. 3, 4). A more specific function is probable for the finer pieces. They are generally about half a meter high or larger, with solid or open bottoms and rolled rims and bases. The latest examples (Figs. 5a, b) have two rows of vertical serpentine or loop handles and plastic decorations such as snakes, birds, horns of consecration, bulls’ heads, or goats. Some also have cut out or painted ornamentation. Many of the tubes which date from Late Minoan IIIB-C have been found in ‘shrines’— small rooms which contain cult objects. Female figurines with upraised arms have been found lying on the floors of some of these rooms and may have fallen from benches along the walls. The figurines are usually regarded as goddesses and often their painted decoration, and even their attributes, correspond to those of the cylinders found with them. It has been suggested that the clay tubes are stands on which offerings in cups or bowls would have been placed before the figurine Cups and bowls are found in association with most of the tubes, and a Late Minoan III stand from Kommos was found in situ with a cup still resting on it (see Fig. 6). Among the sites that have yielded pot stands in probable religious contexts are Gournia, Kommos, Haghia Triada, Gazi, Karphi, Katsamba, Koumasa, and Kannia near Gortyn.

Searching for the antecedents of these Late Minoan III stands, Sir Arthur Evans hypothesized a development from Middle Minoan I drain pipes. Although these pipes are cylindrical in shape and have vertical loop handles, they clearly served a purpose quite unrelated to the later tubular stands, and do not have any religious association. More recently, Late Minoan I stands have been found at Pyrgos. They may represent earlier stages in the development because their general shape is like the later Minoan tubes they differ in having only one or two pairs of vertical handles and simpler relief decoration. The nature of the find place—whether religious or domestic—is not certain.

Recent excavations at Kommos have yielded tubular clay vessels from a Middle Minoan 111 context (Figs. 7a, 7b, 8, 9) which shed further light on the early development of Minoan cylindrical stands. Several fragmentary examples were found, and a complete example is 65.2 cm. high with a diameter of 12.2 cm. at the rim. It is handmade from a coarse, brownish clay. The shape lacks handles and tapers gradually upward from base to rim, with rather sloppily painted bands. From the same context came a lentoid jug with white spirals, stamped with a double axe. Some of the fragmentary examples have more decoration; some show vertical ropework and/or painted strokes (Fig. 8), while others are plain. Although their complete shape is not known, they were probably tall and cylindrical.

The context of these tubes does not seem to be certainly religious, since there were no figurines nearby and their position cannot be determined. Their simple form, with neither loop handles nor any obvious religious iconography, weakens the comparison with the Late Minoan stands that had religious uses. Several other elements, however, including their size and their painted decoration, may imply a connection. Their decoration does not seem closely akin to that of stands found in religious contexts from later periods but they do have decoration, whereas stands found from later periods in secular surroundings tend to be plain. It would seem, therefore, that the Middle Minoan III Kommos stands might find a place as antecedents to the religious examples.

We have seen that the evolutionary pattern of these Minoan stands does not form a straight line. Evidence to date seems to show that there are at least two traditions: stands decorated to varying extents found in religious contexts, and plainer stands which occur in domestic surroundings. That these were used as bases for vessels has been sufficiently proved by the cup found in situ on the Late Minoan III stand from Kommos (Fig. 6). Whether they held only cups or bowls is another question. Knowledge of the extent of foreign influence may shed light on the matter. Approximately contemporary wall paintings from Egyptian tombs demonstrate stands, similar in form to the simpler Minoan ones, being used to support or contain a variety of offerings to the deceased, from bowls and flowers to large trays which are held by two or more stands. Evidence from Egypt also shows a contemporary domestic tradition of stands used in a manner similar to the tomb stands but for objects of a more mundane nature.

The culmination of the ritual stand tradition may be seen in a group of elaborate cylinders from Beth Shan. They date from the early Iron Age and incorporate elements that seem to come From both Crete and the Near East. A good example, illustrated here (see Fig. 10), comes from the ‘Northern Temple’ area. It tapers sharply, with rings at both top and bottom. Snakes writhe on the surface and small birds peer from triangular windows and perch on top of the handles. Many of the elements—rings at rim and base, perching birds, triangular apertures, and sinuous snakes—occur on earlier Minoan stands. The tapering cylindrical shape, however, is more at home in the Near East, and many of the Minoan elements have a Near Eastern history as well. Thus the antecedents of the Beth Shan stands are obscure and are probably mixed.

Stands were popular in many parts of the eastern Mediterranean where they are used by many different peoples who probably responded in a similar way because of common cultural needs. Trade and other contacts may also have contributed to the spread of the idea. The stands were used for humble everyday objects as well as in a variety of cultic rituals. Under the stimulation of their religious use, they developed into fanciful and decorative utensils which contributed to the mysterious aspects of religious cults.

Acknowledgements

This publication was a seminar project in a course on Aegean pottery at the University of Pennsylvania, Graduate Group in Classical Archaeology. The authors wish to thank all those who lent assistance and granted permission to study material under their jurisdiction: in The University Museum, Spyros Iakovides, Curator of the Mediterranean Section; G. Roger Edwards. Keeper of Collections and Curator Emeritus of the Mediterranean Section; David O’Connor, Associate Curator of the Egyptian Section; and Frances James. Research Associate, Near Eastern Section. The material from Kommos was excavated under the direction of Joseph W. Shaw for the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum. The LM IIIB stand from Kommos is being published by L. Vance Watrous who kindly granted permission for its inclusion,

Photographs of stands from Gournia are by R. K. Vincent, Jr., courtesy of the Archaeological Museum, Herakleion, John Sakellarakis, Director. The photo of the LM IIIB stand from Kommos is also by R. K. Vincent, Jr. The photo of the Beth Shan stand is by courtesy of The University Museum. Other photos by P. Betancourt. Drawings are by Debi Harlan (MM III stands from Kommos) and by Mary Ciaccio (Egyptian relief).

When this article was written. Philip P. Betancourt was Chairman of the Department of Art History at Temple University and a visiting lecturer in Classical Archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania. He is currently Acting Dean of Temples Tiler School of Art. He has excavated in Crete for many years and specializes in the archaeology of the Minoan civilization. Brigit Crowell is a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptian Archaeology. Jean M. Donohoe and R. Curtis Green are Ph.D. candidates in Classical Archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania. Mary G. Ciaecio is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cincinnati.

- 7a, b Middle Minoan III stands from Kommos, Crete. Scale is 1:3 for the sherds and 1: 6 for the complete example

- 8 Fragments of Middle Minoan III stands decorated with rope patterns, bands and vertical lines, from Kommos, Crete. (Excavations nos. [from upper left, clockwise] C 4830, rim diameter ca. 9 cm.; C 4916-A, C 4916-B, C 4916-C, rim diameter ca. 10-12 cm.) 9 A tall Middle Minoan III stand from Kommos in Crete. (Excavation no. C2030; height 65.2 cm., rim diameter 12.2 cm.)

-

A fenestrated ritual stand excavated by The University Museum in Palestine. It comes from the Iron Age level of the “Northern Temple” at Beth Shan.

(Museum Object Number: 29-103-830; height 54.5 cm.)