The Kove (or Kombe) have the reputation of being the most difficult people in the large island of New Britain, and they rejoice in it. Feeling themselves superior to everyone around them, they take pride in cheating and bullying the members of neighboring linguistic groups and in resisting the efforts of missionaries and the Australian government to alter their way of life. I began field work in Kove primarily because of interest in their reported conservatism, which contrasted with a more ready acceptance of Western culture among the three other societies in which I had worked in the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. Yet my first visit to a Kove village, in 1966, revealed people who seemed very heavily acculturated. Only a few old women wore traditional clothing, and even they spoke Pidgin English and talked casually of visits to the town of Rabaul, two hundred miles away. Children played with European and Chinese toys, and grown men with footballs and expensive guitars. The men boasted of their capacity for “dry gin,” and proved it by holding competitive drinking parties with other villages at which, wearing freshly polished shoes, they danced modified versions of the Twist and the Conga.

The Kove (or Kombe) have the reputation of being the most difficult people in the large island of New Britain, and they rejoice in it. Feeling themselves superior to everyone around them, they take pride in cheating and bullying the members of neighboring linguistic groups and in resisting the efforts of missionaries and the Australian government to alter their way of life. I began field work in Kove primarily because of interest in their reported conservatism, which contrasted with a more ready acceptance of Western culture among the three other societies in which I had worked in the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. Yet my first visit to a Kove village, in 1966, revealed people who seemed very heavily acculturated. Only a few old women wore traditional clothing, and even they spoke Pidgin English and talked casually of visits to the town of Rabaul, two hundred miles away. Children played with European and Chinese toys, and grown men with footballs and expensive guitars. The men boasted of their capacity for “dry gin,” and proved it by holding competitive drinking parties with other villages at which, wearing freshly polished shoes, they danced modified versions of the Twist and the Conga.

Nevertheless, some incongruous notes could be detected in this apparently modern scene. The village contained a row of men’s houses said to be strictly taboo to women, and decorated with boards carved with grotesque figures. Almost every night, noisy quarrels erupted in the men’s houses, and loud speeches were made from the porches. When I asked about these, my informants said, “The Big Men are arguing about tambu”—the Pidgin name for shell money, in this case strings of small disc-shaped beads quite different from that used by the Tolai of east New Britain. Around the village were scattered carved posts, mostly in the shape of sea creatures, and I was told that they commemorated initiation ceremonies. I saw that even very young girls had their earlobes slit and stretched by the insertion of coils of coconut leaf, and the village catechist told me that he would hold a “circumcision” ceremony for his three small sons as soon as he had collected the necessary tambu. Meanwhile, from my house I could watch groups of men preparing headdresses for dances, and one old man was carving a gigantic human figure for a men’s house while a younger man assisted him and learned the technique. When one man returned from jail, his kinsmen put on a thoroughly traditional ceremony, involving spirit impersonations in their men’s house and killing and flinging out a pig, partly to shame those responsible for getting him jailed and partly to celebrate. It became increasingly clear that both art and ceremony flourished in Kove even more than I had expected, and that the preoccupations of the people had little to do with European culture, however much use they made of its products. Rather, they were concerned with fulfilling obligations to affines (relatives by marriage) while attempting to glorify themselves at the expense of these and of others.

When a Kove man marries, he immediately becomes involved in an endless round of wealth exchanges, most of which take place on occasions marking the development of his first-born child. When that child has his first haircut, visits a strange village, learns to make sago, is initiated, gets engaged, and so on, his father makes a feast and gives strings of tambu to his wife’s family, especially to her brother. In return, they give him “women’s goods,” particularly sleeping mats made by sewing pandanus leaves together. For every fathom of tambu, a pair of mats must be returned. So far, the exchange sounds very simple, but in fact this is only the central act of a series. The father initiates the process by giving “gifts”—a wooden bowl, a dog, nowadays often a bag of rice or a drum of kerosene—to his married sister. Then, when he needs tambu, he calls upon her for repayment. She may have some tambu of her own, but expects to get the bulk of it from her husband. Then she will receive the mats and other “women’s goods” which her brother is given by his wife’s kin. That part of the exchange may stop at this point, but often the husband will have to obtain part of the tambu from his sisters, and so the mats are passed on to them. In this way, the married women are paid twice—first the preliminary gift, and then the return gift. The men resent this fact, and discuss changing the system to eliminate the return gift, but then say that they are too afraid of what their sisters would say to do so.

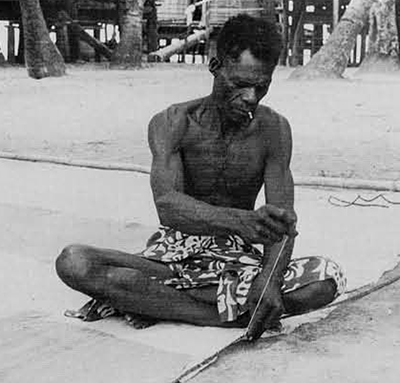

The tambu which the child’s father gives to his wife’s brother is passed on to the women, usually led by the brother’s wife, who made the mats. If the father and his wife’s brother are unambitious, the exchange and the accompanying feast (usually involving the killing of at least one pig) may be small and relatively easy to finance. But many Kove wish to acquire reputations as “rich men,” mahoni, and this involves outdoing others in the amount of tambu dispensed on each occasion. To become a mahoni, it is most useful to have many sisters, all married to wealthy and conscientious husbands, but there are other methods of accumulating tambu when necessary. The most common is to make loans to other ambitious men, these to be repaid at 100% interest. Selling goods to outsiders is another source of funds. The Kove are well located on the various trade routes which end up on the north coast of New Britain, and as daring sailors and ruthless bargainers, who threaten sorcery when persuasion fails, they have made a career of exploiting their gentler neighbors. They also manufacture goods, especially tortoise-shell bracelets and, most recently, woodcarvings in a Solomon Islands-derived style taught by Seventh Day Adventist missionaries, and sell these abroad along with such raw materials as Nassa shells, the source of the Tolai tambu, and trochus shell from which buttons are made. Their customers include Chinese storekeepers and Europeans, and they simply use the money obtained from them to buy tambu at a dollar a fathom.

The Kove are also notorious for allowing their women to marry outsiders and then, reportedly, moving in and stripping their affines of all they possess before taking the woman back home. The beauty and self-confidence of Kove girls have proved irresistible to men of various backgrounds, and the male kin of the girls apparently feel that they have a better chance of profiting from a marriage to some foreign weakling than to another strong-willed Kove. The outsiders are expected to follow Kove custom in paying for their wives.

Individual Kove who have special talents may also employ them to earn tambu. It may be demanded for certain magical services, especially curing, but the easiest way to obtain it is to acquire a reputation as a sorcerer. If a man becomes seriously ill, he and his kinsmen offer tambu to all the known sorcerers whom he might have offended, and they all accept, making a noncommittal but reassuring remark to disguise the exact nature of the transaction. If the victim should nevertheless die, the responsibility is usually fixed on a sorcerer overlooked and not paid. Occasionally a suspected or acknowledged sorcerer is attacked or forced to leave the village, but on the whole, the Kove do not show great disapproval of the practice of sorcery per se, and a victim may be blamed by his closest kin for being so foolish as to offend a powerful man who would be bound to retaliate in this way. Furthermore, it is by the threat of sorcery, only slightly veiled, that the most successful mahoni persuade their debtors to pay up on demand, and a man will receive much higher donations from his wife’s brother if he is thought likely to do something more than just complain about stinginess. Other men may find it very difficult to accumulate the large sums needed to expand their reputations.

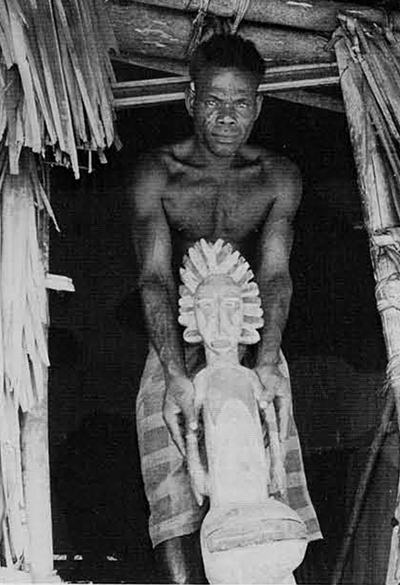

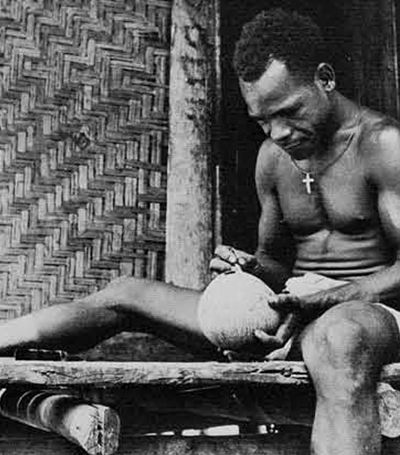

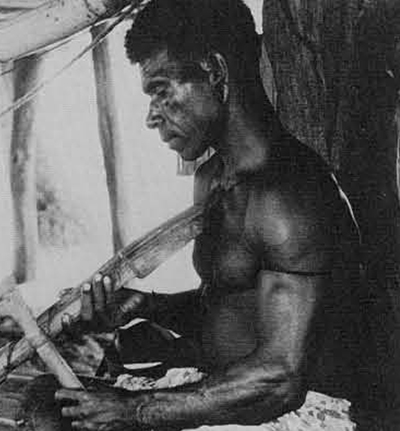

The other principal way of acquiring tambu is by practicing traditional wood carving, including canoe-making. A man who gives his sister particularly well-carved artifacts, such as the so-called “ladles” used for mixing special puddings can ask a great deal of tambu of her in return. An artist may also sell his services to the less talented. Especially for the ceremonies honoring a mahoni’s children, posts and planks must be carved with the symbols of the father’s and mother’s lineages. If the father is not an artist, he pays someone else to make these. The number of carvings increases with the importance of the occasion, culminating in the highly decorated miniature house in which a girl may be hidden for months while her father collects the large amounts of tambu and food to be distributed at the greatest Kove ceremony. It seems surprising that in a society with patrilineal descent groups, girls receive more ceremonial attention than boys, but since, by their own admission, the Kove took over this and most of their other ceremonies from other groups, they do not necessarily bear much relation to other aspects of Kove society. Much of their original significance may have been lost as well. The Kove see them primarily as a way in which a mahoni and, by extension, all members of his lineage and men’s house, can enhance their prestige. The man who has the house erected and the carvings made, who induces the members of his own and related men’s houses to manufacture and dance in elaborate headdresses and masks, who summons various kinsmen and affines to cook feast foods, fish, and travel to distant villages to collect debts and issue invitations, and who finally pays all his helpers and other debtors with an abundance of shell money, mats, and food, is the one who receives the acclaim. The daughter, loaded with adornments and paraded through the village (along with her younger siblings who may be initiated at the same time) is really just the pretext for her father’s acquisition of renown. The older girls, by their own account, do enjoy the attention, and say that the incarceration is not too burdensome; in later life, they continually boast that this was done for them. Nevertheless, the father’s motive in holding the ceremony is only secondarily to honor his children.

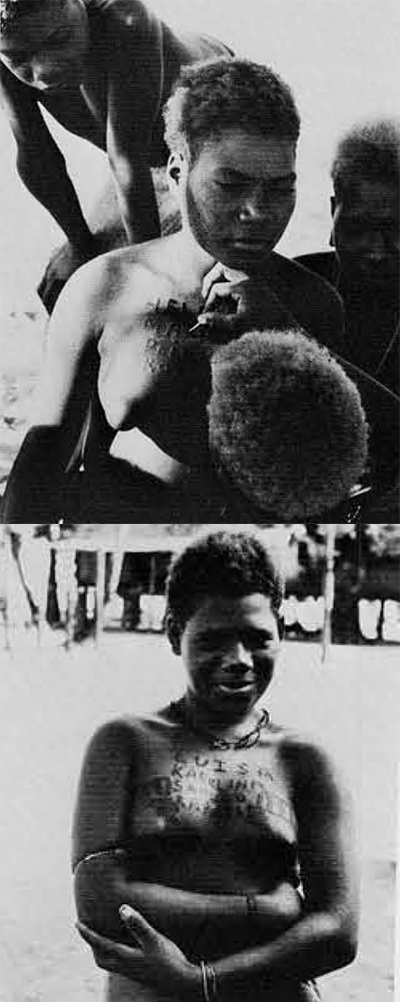

In the past, both boys and girls had their earlobes slit in childhood and then gradually stretched and adorned with earrings, the type depending on lineage membership. Pressures from school teachers have kept boys from having this done recently, but they still undergo penile superincision, in which the foreskin is slit to produce an effect after healing, like circumcision. A boy is definitely not marriageable until this is done, and there is a feeling that girls should not be married until their ears are slit, but the ceremonies can take place at any time from early childhood on. Some girls never undergo the operation, especially younger daughters of poor men or men who die young, but some male relative always sponsors a boy. Each men’s house has its own peculiar form of the ceremony, just as it has its own distinctive dance, mask designs, and noisemaker. Precisely what happens varies according to the men’s house of the child’s father. In many cases, little happens besides a preliminary dance, the operation, a ritual of induction into formal men’s house membership (important only for first-born daughters in the case of girls), and a feast and distribution of tambu. If the father is ambitious, however, he holds an additional and more important ceremony at which the children are adorned and displayed; traditionally, the occasion is the donning of earrings by the oldest child. In addition to the house in which girls are incarcerated, decorated platforms may be built on which the children stand at the height of the ceremony, surrounded by food and valuables which are grabbed by the spectators. Afterwards, the posts of these structures, in the shape of the sea creatures taboo to the child’s parents, are left to decay slowly, and special boards, carved with designs of the parental lineages, are set up outside the father’s men’s house or family house as mementos.

It is not now very common in coastal Melanesia, where heavy European influence has usually been present for a long time, to find elaborate ceremonies of this sort still being carried out. Also, in most such areas, traditional forms of wealth have largely disappeared. At first, like most casual observers of the Kove, I just assumed that, for whatever reason, they were exceptionally devoted to their traditional ways of life, and determined to cling to them. I was accordingly considerably surprised to discover that very little of what I saw was truly traditional; the precontact culture had undergone enormous changes, beginning with partial pacification by the Germans before World War I. As the danger of enemy attack lessened and sails were introduced, the Kove moved permanently onto tiny offshore islands to escape the mosquito-ridden mainland, though maintaining gardens there. They became increasingly sea-oriented, and traveled more and more widely, serving as middlemen and carriers of goods to all of northwest New Britain. Visiting Cape Gloucester at the western tip of the island, they were entranced by the ceremonies, masks, and dances which they saw among the Kilenge.

Some of the leading men began buying rights to these, bringing them home, and enhancing their own status by initiating their children Kilengestyle. The new acquisitions, though assimilated to the magic and ritual already associated with Kove men’s houses, were primarily seen as valuable property. Men could demonstrate wealth and expertise by buying and showing off the ceremonies and art forms, and they could maintain and emphasize the differences between lineages and men’s houses by protecting their copyrights—by violence, if necessary. The most esteemed masks and performances seem to be those which were most expensive, though room has been left for some local and individual invention within all the new forms. Considerable further scope for individual self-expression is allowed in the field of wood carving, from the embellishment of ceremonial objects to that of everyday tools. The Kove are both receptive to outside influences (of certain sorts and from certain directions) and inclined to think up new fashions of their own, yet they themselves are partly responsible for their reputation for conservatism. Over and over they tell me, “We do things the way our ancestors did; that’s the best way,” ignoring the great changes they themselves describe as having taken place within the few generations which separate them from the beginning of their legendary history.

One of the most interesting innovations has been instituted very recently. Tambu used to come from the east, and the Kove had no idea of the ultimate source. The evidence from elsewhere suggests that it was manufactured in New Ireland, in an area which has now totally abandoned traditional trade. The supply of heirlooms was becoming limited when the Bulu people, just to the east of the Kove, were taught or invented a method of making tambu, or a reasonable imitation, out of local shells. The Kove have taken this over, and now turn out fathoms of tambu with the aid of metal pliers, awls made from screwdrivers, and whetstones. Even small children help with the work, as do the women when they have time to spare from producing mats and baskets for the other side of the exchange system. All this is necessary because of recent enormous inflation. Men say that once a few fathoms of shell money sufficed for a bride price; now a mahoni may pay well over a hundred. The wife’s brother is no longer content with two or three fathoms at each affinal exchange; twenty or thirty would be more appropriate. The competition to outdo one another in spending is said by most informants to be relatively new, as undoubtedly is the immense amount of time spent sailing back and forth within Kove and beyond, trying to raise money. Hostilities between communities would have made such travel impossible in the past (and of course it is possible that the present concentration on wealth reflects the loss of opportunity to gain prestige in warfare).

The younger men say that they complain to their elders about their passion for tambu, asking what can be bought with it at the trade store and suggesting that they turn their energies to cash cropping instead. But, in the long run, they are too much afraid of sorcery to defy the system. Anyone who marries a Kove woman simply has to fulfill his obligations to his affines or risk, at the very least, constant shaming and the loss of his wife; at the most, being “poisoned” by his wife’s brother or father, perhaps with the wife’s aid. Women report that they too fear the sorcery of their kinsmen if they fail to extract enough tambu from their husbands. Given all this, plus the practice of not paying debts until forced to, it is not surprising that quarrels over tambu rage incessantly, within families as well as between them. Furthermore, the sponsoring of ceremonies and distribution of tambu is at present the only way in which an adult can receive respect as a “true man” rather than a “rubbish man”; even if sorcery were not feared, men might find it very difficult to reject the “customs of the ancestors,” which in Kove simply means the customs favored by the majority of middle-aged men. As each generation creates its version of the traditional way of life, Kove culture will continue to change, though certainly less obviously and perhaps with less damage to their self-respect than is the case with their neighbors. Because of the presence of a cargo cult which teaches that their culture hero, a half-man half-snake named Moro, went to Australia and America after rejection by the snake-fearing Kove and gave us all the goods of modern civilization, from schools to battleships, the Kove may even find it possible to adopt a much more Western way of life without feeling that they are departing from what is properly “theirs.” Even today, the same middle-aged men who talk of the sanctity of the men’s house and boast of their prowess in tambu distribution, mention calmly that their educated children will accept only Australian money and no longer depend on love magic to attract a spouse. The Kove are committed to resisting forcible attempts to change them, but left in control of their own affairs, with time to rationalize the changes as voluntary and not incompatible with custom and pride, they seem readier than most Melanesians to make and adjust to major shifts in the orientation of their culture, and even to persuade their neighbors to adopt these superior fashions. Their apparent conservativeness is really simply determination to preserve their identity and feeling of superiority as Kove.

- Men performing a Sia dance before an ear-and-penis-cutting ceremony. The Sia was acquired from the west; only the members of some men’s houses have the right to perform.

- In the course of a dance preceding an initiation ceremony, three men act out an imitation of child-birth, using a celluloid doll from the trade store (legs visible) to represent the baby. The intent is purely humorous.

- Masked figures, drummers and dancers prepare to escort the children being honored. They will receive shell money from the father for their participation.

- A boy is given a piece of wood (a knife handle) to bite on as his penis is incised.

- Final moments of a ceremony as the sponsor poses with his family. The weeping boy has just had his penis incised. His father’s sister clowns over him (as part of a joking relationship). The grown girl has just been released from months of seclusion and is displayed in all her finery. The boy on his father’s shoulders is being paraded but has not yet been incised; an older boy has had it done earlier. The headdresses are imported from the east.

- The sponsor of a ceremony distributes portions of shell money to his wife’s kin. The payments to be received by each individual are grouped together on the pole.