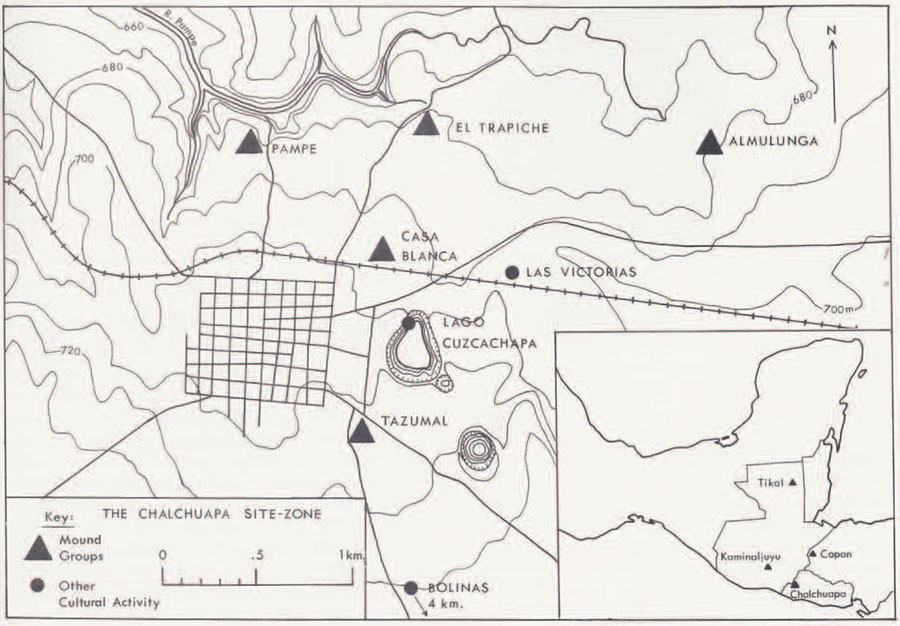

The archaeological ruins of Chalchuapa lie within a broad, fertile valley in the western portion of seldom-visited El Salvador, the smallest of the Central American Republics. Seen today, the site consists of clusters of ruined earth-adobe mounds surrounded by fragments of stone sculpture and surfaces littered by broken cultural debris, all gathered about the fringes of the Spanish Colonial town of Chalchuapa. However, prior to the Spanish conquest, it is evident that Chalchuapa was one of the dominant ceremonial and occupational centers in the valley of the Rio Paz, and a southeastern bastion of Highland Maya culture. Investigations carried out by the University Museum in 1954 and 196668 have shed much light upon Precolumbian Chalchuapa, especially during the Preclassic era, provided much needed information on this little known area of Mesoamerica, and furnished new clues as to the origins, development, and character of Maya culture.

Beginning in 1954, under the direction of Dr. William R. Coe (see The University Museum Bulletin, 1955, Vol. 19, No. 2), and later in 1966-67 under the direction of the present author, the University Museum sponsored extensive archaeological research at the El Trapiche Mound Group, located one kilometer northeast of Chalchuapa. Both of these programs included test excavations along the north shore of the Lago Cuzcachapa, a small lake formed in an extinct volcanic depression half a kilometer east of Chalchuapa. During the summer of 1968, I conducted test excavations within the previously untested Casa Blanca Mound Group (one-half kilometer northeast of Chalchuapa), the largest cluster of ruins at the site.

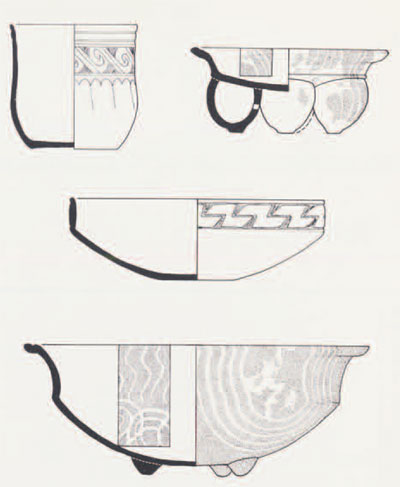

The archaeological investigations at Chalchuapa’s El Trapiche Mound Group have produced significant new data bearing upon the Preclassic cultural development of the Maya, including several surprising and unique discoveries. This research has indicated that El Trapiche was a ceremonial center constructed and occupied during the Late Preclassic era (est. 200 B.C.—A.D. 200). The center is composed of six formally aligned temple platforms constructed of earth and rubble fill and faced with adobe that apparently supported non-permanent temple structures. The largest mound at El Trapiche is Mound 1 (23 m. high), and is among the largest Preclassic structures in the Maya area. The excavation of this mound’s access ramp in 1967 produced a rich array of Late Preclassic ceremonial deposits, including a total of twelve dedicatory pottery caches containing thirty-two intact or reconstructible vessels. These caches have provided an invaluable sample of the diversity and excellence of ceramic art practiced at Chalchuapa during the Late Preclassic. In addition to these pottery caches, the battered fragments of three stone monuments were found buried at the base of the Mound I ramp. The most important of these is a unique, although badly mutilated fragment of a Late Preclassic sculptured stela, containing a seated figure with an extensive hieroglyphic inscription (one relatively undamaged Maya glyph has been identified), all carved in low relief in a sophisticated Maya style. The other monuments consist of the upper portion of a large sculptured effigy jaguar head (the first of this type found in a Preclassic context), and a plain (unsculptured ) monument fragment. These monuments were found where they had been deposited, apparently during a Gotterdammerung ritual of destruction, and are mute testimony of the abandonment of El Trapiche at the close of the Late Preclassic (about A.D. 200). It is believed that this deliberate flurry of destruction and abandonment may have been in response to a local volcanic eruption, for the effects of such a catastrophe were seen in a layer of dense volcanic ash overlying the smashed monuments, as well as blanketing the entire Chalchuapa area.

Another result of the El Trapiche investigations has been the development of the first detailed ceramic sequence for this part of Mesoamerica. This chronological sequence, based upon the analysis of pottery sherds recovered from the excavations, spans much of the Preclassic era:

| Tok Ceramic Complex (Early Preclassic) | est. 1100-800 B.C. |

| Kal Ceramic Complex (early Middle Preclassic) | 800-500 B.C. |

| Chul Ceramic Complex (late Middle Preclassic) | 500-200 B.C. |

| Caynac Ceramic Complex (Late Preclassic) | 200 B.C.-A.D. 200 |

Of particular importance is the pottery of the Tok Ceramic Complex, recovered from an apparent primary deposit deep beneath the base of Mound 1. This material represents the first evidence of Early Preclassic occupation in the southeastern Maya Highlands, and shows close relationships to the ceramics of several early agricultural settlements in Mexico and Guatemala. From this evidence, it seems probable that, during the second millennium B.C., Chalchuapa was initially settled by early agriculturalists migrating southeast along the Pacific coast from Mexico.

The El Trapiche ceramics have furnished important evidence of cultural ties with other Mesoamerican centers throughout the Preclassic era. The closest and most persistent connections are to the massive central highland site of Kaminaljuyu, located near present-day Guatemala City. In addition, previously unsuspected ceramic ties with the Maya Lowlands (especially the sites of Tikal, Uaxactun, and Barton Ramie) have been discovered. It is significant that the first of these Chalchuapa-Lowland ceramic ties occurred during the early Middle Preclassic era (800-500 B.C.), for this was the time of the first known occupation of the Lowlands. This ceramic evidence thus provides the first positive indication that peoples from the southeastern Maya Highlands (including Chalchuapa ) may have contributed to the primary settlements in the Lowlands. Later, renewed ceramic ties occur during the critical period of Preclassic-Classic transition (A.D. 100-300), and suggest that the southeastern Maya Highland population may have been once again involved in the cultural developments of the Lowlands.

The findings discussed above represent some of the more significant results of the University Museum research at Chalchuapa. However, seen against our ultimate goal of an adequate understanding of cultural development at Chalchuapa through all its phases, our work has only begun. Accordingly, detailed excavations at the Casa Blanca Mound Group and the Lago Cuzcachapa are planned for the 1969 season. It is expected that these investigations will probe the Classic and Postclassic eras at Chalchuapa (A.D. 200- 1500), which, when combined with the Pre-classic work completed, may eventually produce an unbroken cultural development span of over 2,600 years, potentially one of the longest sequences yet revealed by archaeological research in the entire New World.