Photograph by Scott M. Patterson, 1982

The towns and small cities of Northern California that cluster between San Francisco and Eureka are best known today for their orderly rows of vineyards and associated wineries. Visitors flock to Mendocino, Lake, and Sonoma counties not just for the wine, but also for the quaint charm of Mendocino Village at the ocean’s edge; the sparkling waters of California’s largest natural lake, Clear Lake (Fig. 1); and the historic Spanish mission in Sonoma. The landscape is largely rural and appears to have changed little in the past two hundred years. The straw-colored summer hills are an immutable presence and the intense heat of August leads to the crunchy carpets of acorns that cover the valley floors in the fall. Torrential rains are common every winter and swollen creeks overflow predictably. The spring still brings lush green clovers; and fields of golden poppies and blue lupines are a predictable sign of summer. But this part of California, the homeland of Pomoan-speaking people who are the world’s best basket makers, has changed immensely over the past two centuries. So have the Pomoan people and their lives.

Early Pomo Environment and Culture

Map by Kevin Lamp

Pomoan people lived in an environment that was much wetter and marshier than today. Their village communities clustered in the foothills along streams and creeks that flowed into river-cut valleys; along the edges of Clear Lake and its islands; and inland from the coastal strip along the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 2). The plants that flourished in these moist soils and sands, such as sedge (Carex spp.), bulrush and table (Scirpus spp.), willow (Salix bindsiana), and creek dogwood (Corpus glabrata), produce roots, rhizomes, and shoots that are pliable and strong (Fig. 3). The Bemoan people, with their genius for creating sustainable life, used these abundant resources to weave houses (Fig. 4), boats, clothing, cooking and food preparation implements, storage vessels, baby cradles, carrying packs, and exquisite feather-covered gift baskets. Numerous other resourcesacorn-producing oaks; grasses with seeds, corms, and tubers; berries; nuts; fish of all varieties; game, large and small; waterfowl; seafood like clams, mussels, urchins, abalone—all contributed to an environment that supported the largest concentration of Native people anywhere on the North American continent. The aboriginal Bemo population has been estimated at about 15,000 around the time of European contact in the early 1800s, based on a variety of data and projections about resource sustainable.

Photograph by Scott M. Patterson, 1982

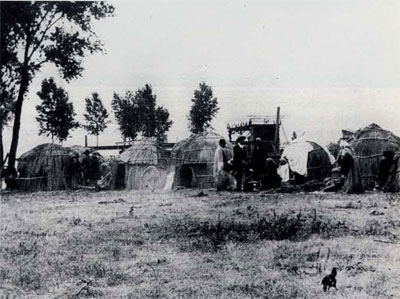

Photograph possibly by O. E. Meddaugh, ca. 1899. Courtesy of Lake County Historical Society, Kelseyville, Cal.

“Bemo” was actually the name of a village in a small valley in Mendocino County; it means “at the red earth hole.” It has come to be the designation for a group of federally recognized tribes from Mendocino, Lake, and Sonoma counties. The tribes were grouped by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on the basis of linguistic research that linked the seven distinct languages spoken by Native people of this region into a language family known as Pomoan. The seven languages are believed to have derived from a single precursor—Proto-Bemo—whose speakers spread out from the shores of Clear Lake.

Pomo villages housed from 30 to 200 people usually in extended family relationships, and bore names like no yow (“under the dust”), ya mob (“wind hole”), mitoma (“splashing with the toes”), and babenapo (“water lily village”). Hundreds of recorded village and camp names demonstrate an intimate knowledge of Pomo territory by its inhabitants (see Barrett 1908). Only one tribal group has maintained its traditional name, the Kashaya (Southwest Pomo), meaning the “agile or nimble people.” As a result of the loss of traditional village community names, the consolidation of villages following depopulation and social disintegration, and the introduction of new community sites, Bemoan people today use English words to identify their current communities, i.e., Hopland, Beint Arena, Coyote Valley, Sherwood, Upper Lake, Big Valley, Robinson Creek. Some of the new Indian-run gambling casinos, however, sport traditional names such as Shoqowa and Shodakai.

Although Pomoan peoples were not farmers, they utilized resource-management techniques like burning, weeding, selective pruning, and cultivating, as well as deliberately timed and patterned harvesting to promote the growth and continuity of local plant and animal life. Each village claimed a defined tract of land on which its inhabitants hunted and gathered. Acorn-producing oaks, pepperwoocis, manzanita bushes, grass seed and “potato-plant” fields, hunting trails, and fish Bing rocks were sometimes controlled by particular families. Outsiders had to ask for group and family permission for access to these resources and for permission to travel through, collect on, or hunt in another village’s homeland. Many groups negotiated reciprocal arrangements, allowing the others special privileges and trading opportunities.

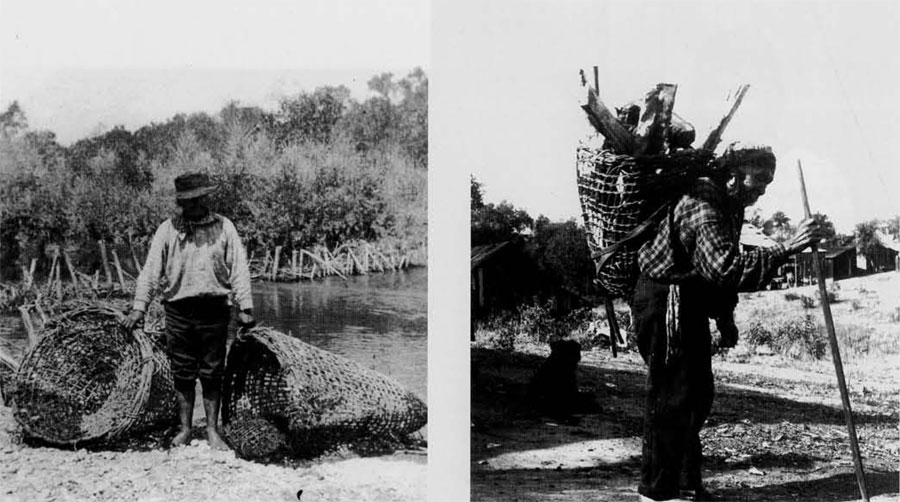

Photograph by Edward Curtis, ca. 1924. NAA 75-14715

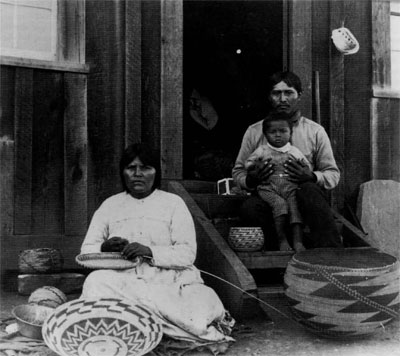

In aboriginal Pomo economic life, there was a clear division of labor that encouraged specialization and enhanced group productivity. Tasks were divvied up by gender rather than by household. All men fished, hunted, built houses, and manufactured fish and animal traps. All women wove baskets, collected acorns and other vegetal foods, and cared for children. Woven implements of tule, bulrush, willow, redbud, and sedge formed the center of Pomo technology. Fish and birds were caught with basketry traps; food was cooked with hot rocks in water-tight baskets; seeds were harvested and prepared with woven beaters, winnowing trays, and collection baskets; babies were carried in baby baskets; acorns were stored in huge woven granaries and pulverized in bottomless hopper mortar baskets; ceremonial occasions were marked with beautifully decorated gift baskets (Figs. 5-9).

Some activities, however, were the province of recognized professional specialists. Such a professional had expert skills that were bought with clamshell bead money or traded for baskets and other goods. Some women were recognized as exceptionally skilled basket makers. Men might specialize in making fishnets or ducknets, arrows, and magnesite beads. He or she might produce more than needed, and offer the excess products for sale. Doctoring was a recognized specialization, as were singing and dancing. Both men and women could engage in these professions.

Occupational and specialized knowledge was passed down in families from father to son, from maternal uncle to sister’s son, and from mother to daughter and nieces. Access to individuals who would teach the specialized skills was dependent on residence. A young married couple often moved from one parent’s village to the other year by year until they chose a permanent village home. This common pattern of alternating residence gave the new couple a wider kin network and extended their possibilities of receiving specialized training.

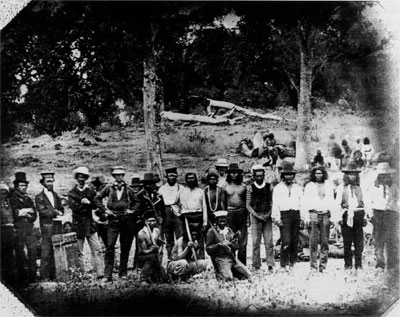

UPM neg. no. S4-140398

(right) Fig. 7. Pomoan man carrying wood in twined basket, Yokayo Rancheria.

Photograph by H.W. Henshaw, ca. 1892. NAA 47750E

The largest Pomo villages included at least one ceremonial structure called a sbane, or roundhouse, where people from smaller settlements and from other communities could come together for prayer and feasting. Although the roundhouse was the physical center for Berno religious life, a sense of spirituality permeated all Pomo activities. The gathering of basket roots, for example, was structured through luck-producing prayers and behaviors that ensured careful harvesting, plant regeneration, and a very real sense of gratitude.

White Rabbits Come

“White Rabbit gonta devour our grain, our seed, our living. We won’t bave nothing more this world.” (Northern California Indian dream prophecy)

Although early records describe non-Indian travelers through Pomo country, the first prolonged contact with outsiders occurred when Russian traders built a commercial establishment known as Fort Ross in Kashaya Pomo territory in 1811. Accompanied by Aleut hunters, the Russians developed both trading and intimate relationships with the Kashaya, who called them the “undersea” people because their boats emerged out of the horizon as though they were coming up from under the sea. The Russians lived and hunted along the Sonoma and Mendocino coast until 1842 when they abandoned Fort Ross and returned to Alaska and then home to Russia. Some museums there maintain excellent collections of Porno baskets and cultural artifacts from the time of Fort Ross. The major waterway through Pomo territory to the north is called the Russian River as a result of this 30-year association.

Photograph by H.W. Henshaw, ca. 1892. Courtesy of Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, Cal.

Although Spanish ships had made landfall on the California coast from the 17th century on, the first Spanish land settlements were established by missionaries. In 1769 they started a chain of missions that stretched from San Diego north to San Francisco and Sonoma. They thereby added most of Alta California to the Spanish empire which already included much of what we today call the American Southwest. The Mexican Revolution of 1810 and subsequent independence from Spain in 1821 transferred sovereignty of these lands to Mexico. Up to this time, there was little interaction between the Spanish settlers and the Berno. By 1834, however, the California missions were secularized and became privately owned ranches in need of laborers. The Pomoan people were never forced into the infamous missionization process through which thousands of Indians lost their names, their languages, their culture, and their lives. But from the 1830s on, periodic raids were made by Mexican rancheros into Pomo territory to capture men and press them into service as vaqueros (cowboys). As a result of this contact, many Spanish words and new technologies became part of Pomo vocabulary. Tragically, so did infectious diseases like measles, smallpox, malaria, and syphilis. Epidemics in the 1830s killed an estimated 70,000 Indians in the area of northern California.

In 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican American War and Mexican rule north of the Rio Grande. The Gold Rush of 1849 and statehood in 1850 brought thousands into California. In short order, the Americans, or Anglos as the Mexicans called them, left the goldfields and crowded onto Indian land. They competed in hunting; they drove the game away or devastated whole animal species through the use of rifles. Passenger pigeons and grizzly bears became extinct in California. They closed the streams where Indians fished by diverting them into flumes for mining or manufacturing. They cleared and fenced the places where berries, seeds, and bulbs were gathered. They fed the acorns, the staple food of the Bemoan people, to their hogs. And in these everyday activities of homesteading, they destroyed the livelihoods of thousands of California Indians. Yet wider settlement by Anglos was supported and encouraged by California’s legislature and by the government of the United States.

Photograph by H.W. Henshaw, ca. 1892 NAA 47750A

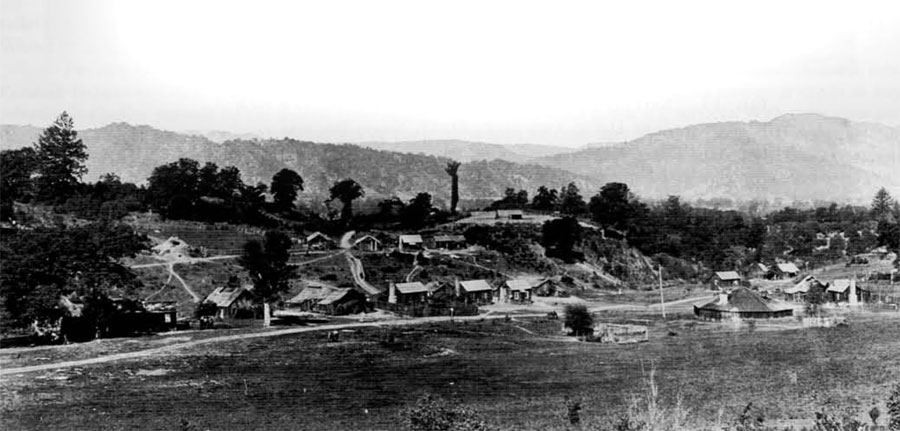

Not surprisingly, serious clashes occurred between settlers and Indians. The murder of two Anglos in Lake County by Indians they had savagely exploited prompted retaliatory violence by the United States Infantry (see McLendon, this issue). Northern Mendocino County was the site of a series of preemptory raids and massacres by a state-supported vigilante group, the Eel River Rangers, that were so vicious and devastating they prompted a legislative hearing and the name “Mendocino Wars.” The federal government recognized a need for intervention and sent a team of treaty makers to California in 1851 to negotiate offers of safe spaces, education, tools, and livestock in exchange for Indian relinquishment of traditional territory and the substitution of reservation life for traditional culture. Eighteen treaties were eventually negotiated, but the United States Congress refused to confirm the treaty lands and the treaties were “lost” until the turn of the century when California Indian activists and others rediscovered their existence. Some reservations were established anyway, for the “protection” of Indians. In Mendocino County, Pomoan people were forcibly marched to Mendocino Reservation on the foggy Pacific coast where Fort Bragg was created. They were also taken to Round Valley Reservation (Fig. 10) in the center of the Inner Coast Ranges, where they joined the Yuki (whose homeland it was) and other Indian tribes who had also been brought there.

Changes in Pomo Households

As a result of both the onslaught of epidemic disease and the genocidal policies brought by the continuing influx of settlers into the Pomo homelands from the 1850s on, traditional culture and family life were violently uprooted. The Berno village communities were eradicated, and the population of Pomnoan men was severely reduced. Pomoan men lost all their traditional avenues to power and authority, and ceremonial and political offices were destroyed. Pomnoan women, in contrast, were forced by circumstances to take on new roles, behaviors, and tasks.

From a large-format daguerreotype, photographer unknown. Courtesy of Held-Poage Research Library, Ukiah, Cal., Robert J. Lee Collection

Traditionally, Pomoan women were totally immersed in the time-consuming domestic chores of food gathering, food preparation, and child care. Although important as family historians and keepers of wealth, Pomnoan women did not have as many opportunities to achieve personal prestige as did men. While some were known as powerful healers, their major value was in their lineage or family—the status and wealth of their relatives—and their reputation regarding their domestic skills. Their modesty and adherence to appropriate behavior were what gave them esteem. Because the family was so important to Berno society, it was extremely rare for a woman to live alone as head of a household.

After the arrival of the settlers, Pomoan women became the heads of increasingly male-absent households. They were able to maintain their families successfully in the newly imposed economy because of their ability to earn goods or money as domestic workers. They were hired in local towns to wash and iron clothes and occasionally cook for pioneer families. Their knowledge of the English language and Euro-American behavior grew as a result of their intimacy with White households, increasing their power within their own communities.

Photograph by A.O. Carpenter, late 1890s. Courtesy of Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, Cal.

Pomnoan women had a separate relationship with White men. Although often the victims of rape, sexual exploitation, and abuse, they also received favors and money from the White men who fathered their children (Colson n.d.; Hurtado 1988). This situation resulted in much anger and hostility between Indian and White women. The relegating of Indian women to the most demeaning and backbreaking tasks such as laundering, and the subsequent freeing of White women from such work may have had a relationship to the repressed anger of sexual competition (Colson n.d.:34).

As the real hardships of frontier life’ diminished and places like Mendocino County approached the “civilized” sameness of the Midwest, more White women emigrated. Newly arrived girls looking for work were hired in place of Indians, isolating Indian women from daily contact with White men. The segregation of Pomoan women from White households became so complete that from the mid-1870s until as late as 1940 only one Indian woman worked in the town of Ukiah (as a laundress for the local Catholic convent), despite the fact that many Pomoan girls found work as domestics in the Bay Area.

New Livelihoods

From around 1860 through the turn of the century, some Pomoan people found employment on local ranches and established small communities under the protection of ranchers. Men chopped wood, sheared sheep, and rode with mule pack teams; men and women trained vines and picked hops. A woman could pick 300 pounds of hops a day and take home $16 for her season’s work. Cut wood sold for $2 a tier (about three cords) and each sheep sheared brought in 6 to 7 cents. A good worker could shear 97 sheep a day. During harvest seasons, men and women also picked beans, prunes, and pears. A typical day entailed 10 to 14 hours of work with a daily wage of $1.00. But despite the long hours, many Indians enjoyed the outdoor life, camping with their families, meeting others, gossiping and playing cards.

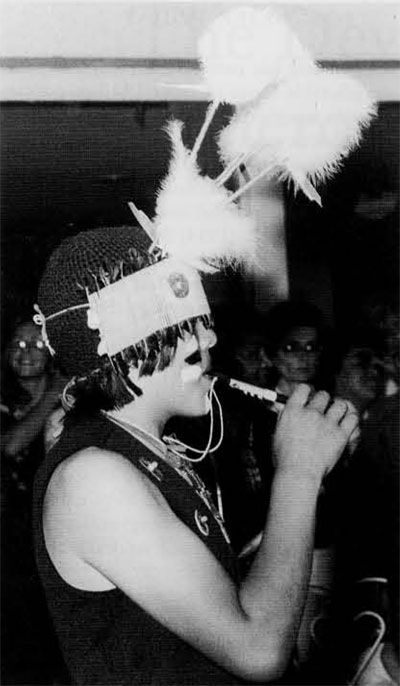

In 1870, twenty years before the Ghost Dance of the Plains Indians, a messianic religion swept westward from the Nevada Paiute to California and through Berno territory (see DuBois 1939). Through the medium of the Bole Maru, a spiritual revival that followed this 1870 California Ghost Dance, some Pomoan women gained tremendous personal and political power that survives to the present day (Fig. 11). Through the agency of “dreaming,” they constructed religious events and beliefs that had ethical and political importance in redefining Indian values, goals, and relationships to Whites (Oswalt 1964:218, 318-31).

Photograph by A.O. Carpenter. Courtesy of Held-Poage Research Library, Ukiah, Cal., Robert J. Lee Collection

Perhaps as a result of the combing together of Pomoan Indians at Ghost Dance ceremonies and the privatization policy pursued by the federal government through the Dawes Severally or Allotment Act of 1881 as well as a growing understanding of the imposed cash-and property-based economy, many groups of Pomoan people from the late 1870s on began legally buying land from White homesteaders and creating self-owned communities or rancherias (Fig. 12) (see McLendon, this issue). Between 1878 and 1892, at least six separate self-owned communities were established. Most of these properties were eventually lost due to unpaid taxes and mortgage payments. The people from these communities were eventually relocated to other property bought by the federal government as trust land. The most ironic situation is that of Yokayo Rancheria, land purchased in 1881 with money contributed by many Indians native to the area of today’s Ukiah. Because this land is still held communally as private property, residents of the ranchenia are not recognized as belonging to an Indian tribe by the federal government.

New Roles for Pomo Women

Photograph by H.W. Henshaw, ca. 1892. Courtesy of Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, Cal.

Pomoan women became less involved with subsistence tasks as they acquired money or credit to buy food and other goods and services. With more time and a need for cash, they began to make baskets on commission. Some women established reputations as expert weavers and formed relationships with collectors. With the more or less stable separation of the two societies, Indian and White, White women could safely admire the arts and crafts of traditional Pomo culture, far removed from any real interaction with its artisans. The new style set by the Craftsman movement, among others, prompted women to demand Indian arts (see Smith-Ferri, this issue). As a result of this market, Bemoan women could use the traditional women’s art of basket making to their economic advantage (Fig. 13). They were able to secure their new roles as providers and also acquire personal prestige in both White and Indian circles. At the same time, they were actively involved in preserving and transmitting at least part of their cultural heritage through the practice of marketable crafts. A price of $30 to $50 dollars for a basket of several months labor was significant compared to other wages. In fact, Pomoan women began receiving such serious money through the sale of their basketry that the San Francisco municipal administration banned the purchasing of Pomo baskets by City-sponsored museums. This Labor-friendly administration thought that the high prices for baskets allowed Indians to work in other jobs for very low wages and thus created an unfair employment advantage that kept White laborers out of the market.

It was at this time the White women also became involved in the preservation of traditional Indian cultural heritage, Although their emphasis was on nostalgic and romantic notion of the loss of the past innocence and natural existence, and not the reality of changing Indian culture and need. Women such as author Helen Hunt Jackson, businesswoman and art dealer Grace Nicholson, and painter Grace Hudson (see Smith-Ferri, this issue) sought to preserve and promote the beauty of California Indian culture. Some other White women, motivated by religion and social service, pressed for political and social reforms for Indians. The earliest schools for Pomoan woman were run by nuns, and other female missionaries. White women lived and worked on the rancherias as teachers and welfare advocates; and women from both cultures worked actively to promote Indian rights. Although the early encounters between Indian and White women led to estrangement on many levels, their growing mutual interests, in economic independence, their appreciation of aesthetics, their concern for cultural preservation, and their practice of spiritual beliefs contributed to a complimentary and reciprocal partnership.

Pomo Life Today

Photograph by Scott M. Patterson, 1984.

Pomo culture has persisted through a haphazard and unpredictable series of federal Indian policies that have brought significant and contradictory changes and challenges about every 20 years. The Allotment Act (1881) split federally protected Indian land into privately owned parcels; the California Homeless Indian Appropriation Acts brought tribal land back (1906). The Indian Reorganization Act (1934) forced tribes into a contrived governance by elected tribal councils; the Termination Acts (1951) severed that relationship; the “unrermination” suits brought by tribes against the federal government starting in the 1970’s restored tribal land and commnities. The 1990s have been characterized by cultural revival and revitalization among the Pomoan peoples. Tribes have employed different strategies, including Indian gaming, to deal with non-Indians in order to maintain a degree of political and economic automony. Native foods are used at social and ceremonial events. Kin relations are essential. Traditional son and dance continue (Fig. 14). Pomo language classes are growing in importance. Tribal museums and programs are generating community interest, mobilizing knowledgeable people and teaching old skills. Indian doctors practice traditional medicine and talk to the ancestral spirits in the hills. And Pomo basket making continues to fascinate basket makers, scholars, and the general public.

Barrett, Samuel A.1980. The Ethnogeography of Pomo and Neighboring Indians. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 6, no. 1. Berkeley.

Colson, Elizabeth

n.d. “Acculturation Among Pomo Women.” Unpublished manuscript on file Sonoma State University, Cultural Resources Facility, Rohnert Park, Cal.

DuBois, Cora

1939. The 1870 Ghost Dance. Anthropological Records 3:1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hurtado, Albert L.

1939. Indian Survival on the California Frontier. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Levene, Bruce et al.

1977. Mendocino County Remembered, An Oral History. Vol. 2. Ukiah, CAl.: Mendocino County Historical Society.

NAA

National Anthropological Archives, Bureau of American Ethnography, Correspondence, National Museum of Natural History, smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Oswalt, Robert L.

1964. Kashaya Texts. University of California Publications in Linguistics 36. Berkeley.