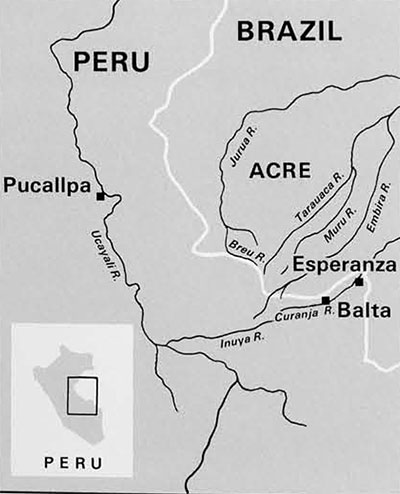

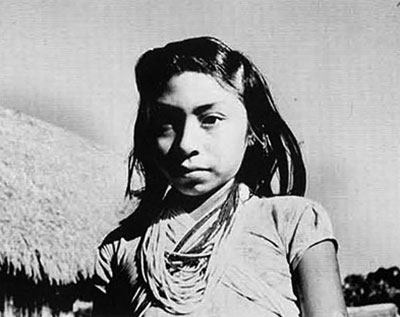

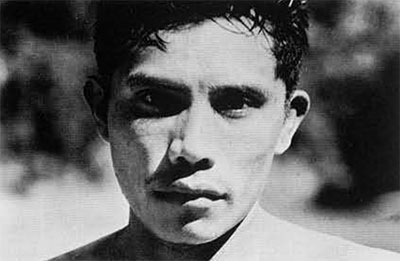

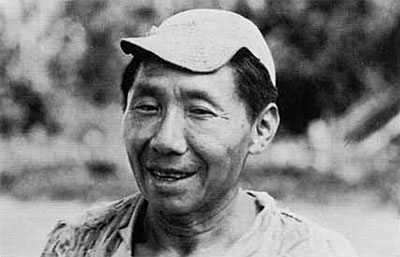

In the Summer, 1965 number of Expedition, we published a copy of the first letter written by a Cashinahua in his own language, together with an account by Kenneth Kensinger of how the letter came to be written. The illustrations were from photographs made by Mr. Kensinger in 1955-1958. Several of the photographs in this new article by Mr. Kensinger and in that by Dr. Johnston show the same individuals in 1966. All of these photographs were taken by Dr. Geoffrey F. Walker. –Editor

In May of this year (1966), I returned to Balta, one of the Cashinahua villages on the Rio Curanja of southeastern Peru, to study the tribal medical system. Throughout my four-month visit, both in formal informant sessions and in informal chats, no matter what the general topic of discussion, sooner or later my informants would get around to discussing the changes which have been taking place during the last two decades. Change, its advantages and disadvantages, has become the major preoccupation and topic of discussion of the adult Cashinahua men, and to a lesser degree of the women.

In May of this year (1966), I returned to Balta, one of the Cashinahua villages on the Rio Curanja of southeastern Peru, to study the tribal medical system. Throughout my four-month visit, both in formal informant sessions and in informal chats, no matter what the general topic of discussion, sooner or later my informants would get around to discussing the changes which have been taking place during the last two decades. Change, its advantages and disadvantages, has become the major preoccupation and topic of discussion of the adult Cashinahua men, and to a lesser degree of the women.

Twenty years earlier, the Cashinahua had been living along the small northern tributaries of the upper Curanja, where their fathers and grandfathers had settled after separating themselves from their more progressive kinsmen living on another river system across the border in Brazil. The reported cause of the tribal split was disagreement over what should be done about the Brazilians who had begun to move into the area in search of rubber. Contacts between the two groups were sporadic, but seem to have had much influence on the Peruvian group, in that it was from their Brazilian kinsmen that the Peruvian Cashinahua received their first metal tools.

They quickly realized the technological advantages of metal axes and machetes. When the tools were out, they decided that they should go in search of new ones, even if it meant making contact with the nawa, the foreigners.

Through occasional and often hostile contacts with their downriver neighbors, the Marinahua, they learned of traders living in a Marinahua village near the mouth of the Curanja. After considerable debate, a group of eight men, under the leadership of a dynamic young headman, Napudiun (Napoleon, the name he was given by the Peruvian traders), made their way downstream in four hollowed-out palm logs. They traveled for ten days to a Marinahua village about a day’s canoe trip below the present village of Balta.

The trader was not in the village. Since they were going to make their way back upriver on foot, and they were unfamiliar with the region, they decided to go no further.

The Marinahua convinced them to stay with them until several of their young men could go by canoe to bring back the trader. However, late in the evening of the third day of their visit, they joined their hosts in a nixi pae drinking party. [Nixi pae is a hallucinogenic brew made from the ayahuasca vine, drunk by the Cashinahua in order to learn from the spirits about events removed both by time and space.] In their visions, all eight men saw themselves being attacked and slaughtered while they were sleeping. And so, after their hosts retired to sleep, they fled for home.

Six days later, the trader, along with two canoe-loads of Marinahua, caught up with the fugitives. He gave each of them either a machete or a metal axe and promised them more of the same and other goods if they would work wild rubber and lumber for him. He also urged them to move downriver so that he could supply them more easily. They enthusiastically agreed and continued on to their villages with the news of their success.

The Cashinahua threw themselves into their new work with diligence, eagerly awaiting each visit of the trader. Several villages moved to new locations closer to the mouths of the tributaries. A few men, including Napudiun, even took their families and went to live with the trader in a Marinahua village. Due to the deceit and duplicity, and the harsh and unfair treatment they received from the trader and his friends, they quickly became disillusioned. Thus, when Napudiun died, allegedly due to Marinahua sorcery, they withdrew, threatening to get revenge, and contacts with the outside world became less frequent. However, they had acquired a taste for the goods of the foreigners, a taste which only the trader could satisfy.

Shortly after the Brazilian photographer-ethnographer Harald Schultz visited several of their villages in 1951, an epidemic decimated the population. The remaining Cashinahua were discouraged and disillusioned. Their contacts with the Peruvian traders and the Marinahua became increasingly less satisfactory and more hostile.

Early in the summer of 1952, two men arrived from one of the Cashinahua villages on the Embira River. They told glowing stories about the generosity of their Brazilian patrons. The clothing they wore and the goods they brought with them were all the testimony their kinsmen needed. Thus, in late September or early October of that year, they migrated en masse to Brazil.

However, if they were looking for Eden, they did not find it. The manner of life of their Brazilian kinsmen was strangely different, being patterned after the ways of the traders who lived nearby. Both the Brazilians and their kinsmen treated them as poor naked country cousins, who had yet to learn how to be “civilized.” When they were asked, they were given trade goods, but then had to work for months to pay their debts. They found in the new situation all of the disadvantages of the old one from which they had fled. To these were added another, more irritating than all the others–the constant presence of aliens and alien ways.

After a year, two extended families decided they preferred the old ways and. on the pretext of going upriver to hunt wild rubber, left with all their goods to return to the Curanja. During the next six months, two more extended families followed their example. These, then, were the people with whom I made contact in July of 1955, and with whom I began my linguistic and ethnographic studies.

At that time, their contacts with the Peruvian traders were sporadic and infrequent, generally occurring not more than twice a year. The Cashinahua expressed great dislike for the foreigners, but they wanted and needed the goods the traders had to offer. Each visit of a trader would be followed by a new sickness which would sweep the village. The Indians were completely at the mercy of the trader, who set the prices for both his goods and their products. They were continuously and increasingly in his debt. He treated them with contempt, took their women at will, and carried off their young boys to work in his gardens in Esperanza.

To the elders, the price for the foreigner’s goods was too high. As one informant told me this summer, “We decided that life was not worth living. I gave my wife medicine to sterilize her so that she would have no more children. I gave the same medicine to several other women. When a woman became pregnant, I gave her an abortant, if she asked for it. Others killed their babies when they were born.”

“But,” he continued, “you came to live with us. You wanted to learn our language and our ways, You told the patron that his prices were too high, and that he should treat us with fairness. He feared you because you talked strongly [forcefully, with conviction] and because you came from the other side, from where his chief lives. Therefore, he treated us betterm at least when you were living with us.

“When you were not here, we talked thus, ‘He came from far away, from beyond the edge of the horizon. He came to study our words and customs. He lives with us and eats with us. When we go hunting, he goes. He paints his body as we do and joins in our ceremonies. He does it even when the foreigners are in the village and isn’t ashamed. The ways of our ancestors are good.’ Thus we said to one another.”

However, many of the younger men who had tasted the ‘good life’ in Brazil, were of a different mind, and as they assumed more of the responsibilities of village life, they increased their contacts and trade with the Peruvian patrons. They were encouraged in their “opening to the outside” by the influx of nearly two hundred Cashinahua who migrated from Brazil between 1959 and the present, who came bringing with them the foreign ways they had learned in Brazil.

As a result, the Cashinahua have been changing rapidly. Some of the changes are superficial accretions of foreign things like aluminum kettles, clothing, dances, medicines, and alcohol. Other changes are more significant, especially in the area of social relations. There has been a shift of focus from community-wide activity to the activities of the extended or nuclear family; e.g., they now generally eat in small family groups rather than the daily communal feast; cooperative hunting, fishing, and gardening are a family effort rather than a community affair.

Since 1955, the Cashinahua have moved progressively closer to Esperanza, so that at present the most upriver village is less than half the distance from the mouth of the Curanjo to the village whence I began my studies. One village on the Purus River, composed entirely of recent Brazilian migrants, is less than two hours by canoe from Esperanza, where the establishment of a Catholic mission and school and the initiation of biweekly DC-3 air service from Pucallpa and Iquitos have attracted several prosperous new traders who have established stores and trading posts in the hope of striking it rich in the booming ocelot and jaguar skin market.

Contact with the outside has increased greatly, so much so that during this past summer, traders visited the village on the average of once a week, and the Cashinahua visited Esperanza on the average of one canoe-load every three weeks. The Cashinahua now have more goods and money than they dreamed could exist twenty years ago. But they also have more sickness, more drunkenness, more fighting and stealing.

In spite of the relative affluence, there is a great deal of discontent. As one informant told me, “Since my father seized [contacted] the foreigners, our manner of living has changed much. The foreigners have given us so many good and useful things. They have also given us much that is bad. I have even heard some of the young men say that they hope that their sons and daughters will marry outsiders. When I hear such things, I wonder if my father did well, when he seized the foreigners. Yes, our ancestors lived well. I would like to live as they did, but only if I could still have my shotgun, my mosquito net, my metal tools, and…”.