Museum Object Number: C179

When in the spring of 1966 the People’s Republic of China stopped the publication of all archaeological journals all of us were inclined to believe that excavations had come to a complete standstill. Some newspapers even recorded that in the course of the Cultural Revolution Red Guards had damaged or even destroyed historical buildings or works of art. Knowing the attitude of the Chinese government towards their cultural heritage I doubted this from the beginning, all the more so because I heard that precautions such as the closing of museums or historical buildings including the Forbidden City in Peking had been taken to prevent damage.

Reports from China now confirm that nothing of great value had been destroyed and an exhibition held in Peking in the summer of 1971 in one of the palaces of the Forbidden City proved that archaeological work has continued all through the Cultural Revolution up to this very day. Very summary descriptions and pictures of the most spectacular of the 2000 objects in the exhibition appeared first in some Chinese and Japanese papers and in some popular publications of the Foreign Language Press in Peking. Since January 1972 two archaeological papers Wen-wu and Kaogu have resumed publication and are reaching us slowly. Their excavation reports have been made use of in this article as far as available at the time of writing. In general, excavations followed the lines of procedure as outlined in my previous article, though in addition to archaeologists and local people, in the course of the Cultural Revolution members of the army were often included in the workforce at the actual diggings.

The range of discoveries covers again the period from Sinanthropus Pekinensis and his implements to objects used by people in the 17th and 18th centuries A.D. A wealth of new material has been brought to light, each excavation deserving an intensive study. In a short article nothing more can be done than to select some particularly interesting objects dating from successive periods, report on a few excavations and, if possible, comment on their historic implications.

Among the excavations of late neolithic sites may be mentioned one in the P’i-hsien district of northern Kiangsu where in 1966 290 tombs were excavated, containing about 3000 objects made of stone, jade, bone and pottery. Outstanding was the discovery of a small, painted pottery model of a house with a conical roof and of a vase painted in a style not seen previously. The discovery of another neolithic site in Yeh-tien ts’un in the Tsou-hsien district in Shantung in 1966 augments considerably our knowledge of the advanced civilization and great variety of pottery vessels, jade and stone rings and implements typical of the Lungshanoid phase of development in Shantung and Kiangsu and, in particular, of the Ch’inglien-kang culture. The ten tombs excavated on this site were often built one on top of the other, causing damage to the contents of the tomb below. A number of tripods (Fig. 1), bowls raised on high openwork feet and black pottery cups on a candlestick-like high ringed stem, testify to the elegance and sophisticated taste of the people in this region. Painted borders as those on the tripod (Fig. 1) are rare; they were found only on one other tripod and on a bell-shaped object described as of “undetermined” use. It reminded me of the much later bronze bell-shaped dodakus which during the Yayoi period in Japan were buried near tombs or other places.

Wên-wu 1972. No. 1. Pl. V.

Four large tombs dating to the Shang dynasty were excavated in 1965 and ’66 in Su-fu-t’un, Yitu district in Shantung. Similar to those in the Anyang region, they were laid out in the form of a cross with tomb ways on all four sides. All had been robbed previously but one still contained the heads and decapitated skeletons of 40 people sacrificed at the time of burial. Contrary to Eater pious Confucian commentators and historians, excavations reveal that the custom of sacrificing human beings at the time of funerals did not completely stop in the Chou period; there are even a few isolated instances in the Han period. A tomb of the Warring States period excavated in 1969 in Hou-ma in Shansi contained the remains of 18′ human victims—among them some children—placed in a ditch running along all four sides. One of them, perhaps a criminal, was found still fettered with an iron ring round his neck.

In general, the ritual bronze vessels of the Shang and Chou periods excavated during this time—as far as they have been published—conform more or less to well established types and do not offer any startling new shapes and decorations. One excellently preserved jar with a swing handle (yu type) dug up by a farmer in 1970 in Ning-hsiang district in Hunan was filled with over 300 finely carved jade rings, tubes and so forth. The discovery is of special interest insofar as previously a hoard of similar jade pieces had been found in this region.

In 1971 in Hsiao-tun in the Anyang region of Honan, a hoard of 21 oracle bones was discovered, ten of them inscribed. Interestingly, Professor Kuo Mo-jo in discussing them interpreted two hitherto unexplained anthropomorphic ideographs, which also occur in inscriptions on ritual bronze vessels, as referring to certain invocation rites for rain and healing. These bones date from the later part of the Shang period, that is, the time of Wu-yi and Wen-wu-ting (13th century B.C.).

Outstanding only because of its beautiful jade-green patina is a ritual vessel in the shape of two owls back to back, discovered in 1966 in Ch’ang-sha in Hunan (Fig. 2). It resembles closely one found some years ago in Anyang; both had lost their lids. Owl vessels and pottery owls are among the most common objects in tombs of the Shang period. In 1968 among 23 ritual bronze vessels found in a tomb in Wen-hsien was a tripod with a handle, outstanding because it was decorated on all sides with a set of three owls with outstretched wings, a rare, though not completely unknown, motif.

The multifarious use of owls in the Shang period is puzzling and raises a problem. However, nowadays there is a tendency to ignore problems of possible meaning or purport and to interpret the strange shape and decorations of these ritual bronze vessels as due to nothing else but “pure play with form” and the decorations as “iconographical meaningless, or meaningful only as pure form—like musical forms,” an approach which would deprive our study of its importance for history, limiting it to questions of style and influence. Owls are often mentioned in Chinese literature of the early period. In short, as in many other countries (e.g. England and Germany) they were considered birds of ill omen (or harbingers of death), most likely due to their nocturnal habits and the eery sound of their hooting. The fact that they were birds of night would, on the basis of association, in ancient China have connected them with the fear-inspiring powers of darkness and consequently linked them with winter, that is with the time of destruction and death in nature—implying the victory of the yin forces. This would explain why owls in ancient China are said to have been eaten or sacrificed at the time of the winter solstice or in spring when the forces of yang are in the ascendancy and the powers of darkness defeated. We may thus further conjecture that vessels in the shape of owls were used, in particular, in rites at this time of the year, or in general, included in the set of vessels used at seasonal rites or at funerals.

A considerable number of Western Chou ritual bronze vessels have been discovered in the province of Shensi, the homeland of the Chou kings, some of them even in the neighborhood of the ancient capital Hao-ching in the Ch’i-shan district, the principality of the Chou family before their conquest of the Shang. Yet, so far as material has been published, none of the vessels found in this place date back to the Shang period. Among them may be mentioned a ritual bronze vessel in the shape of an ox with a small tiger on its lid, a bronze color-mixing bowl and a square bronze cauldron. A ritual bronze food basin (Yung yu) excavated in 1969 in Lan-tien in Shensi has a long inscription (125 characters), interesting especially because it contains the name or title “Hsing peh” mentioned in inscriptions on other vessels dating from the early Western Chou period.

The large ritual bronze vessel (hu) (Fig. 3) was found in 1969 in Sung-ho-chu in the Chingshan district of Hupeh in a hoard together with a great number of bronze objects, among them 38 ritual vessels and many harness fittings for horses, altogether 97 objects. Ten of the ritual bronze vessels carried an inscription; in six the name Tsang and in two the name Huang were given as donors of the respective vessels. Differences in style indicate that this hoard contained objects dating from the later part of the Western Chou to the early part of the Ch’un-ch’iu period. They resemble those found in the famous cemetery of the Kuo people in Shang-ts’un-ling mentioned in my previous article, dating from about the same period, the last possible date being 655 B.C. Apparently the vessels in this hoard were the precious heritage of a feudal family and had for generations been used in ancestor worship. Some still contained bones, e.g. of chicken, pigs, sheep, proving that they had been in use till shortly before their sudden burial. The Dukes of Tseng are a very old family, one branch claiming to be descendants of the legendary Emperor Yu, the founder of the Hsia dynasty; their clan name was Sze. Viscounts or dukes of Tseng are mentioned several times in the Ch’un-ch’iu, “the Spring and Autumn Annals” (722-481 B.C.) and the Tso-chuan (e.g. 646, 640, 567, 538 B.C.). It is known that there was a small state of Tseng in what is now the province of Shantung but there are entries in the Ch’un-ch’iu suggesting that there existed more than one petty state of Tseng, the precise location of some not yet identified. The discovery of the hoard speaks for the presence of one in the region of Ching-shan. The clan name was Chi (family name, Huangti). The Prince of Huang apparently resided not far away and the two families seem to have intermarried. We don’t know what caused the sudden burial. It may or may not be connected with a tragic incident reported in the Ch’un-ch’iu in the year 640 B.C. when “the people seized the viscount of Tseng and (yung) used him.” In this context the word “used” means that he was made a sacrificial victim and killed at an altar at the bank of a river. This event, though quite justifiable in ancient times, would have caused the members of his family to fear for their own survival and to hide their most precious or even efficacious possessions. Or, alternatively, an attack undertaken in 649 B.C. against the Prince of Huang may have endangered them directly. In general, during the Ch’un-ch’iu period many small feudal states were liquidated and swallowed by their powerful neighbors. Whatever the cause, the fact that the treasure was never retrieved speaks for a major family disaster in the course of the 7th century B.C.

Among discoveries dating from the later Chou period, the Chan-kuo, the time of the Warring States, may be mentioned 25 painted and incised stone chimes discovered in 1970 in the Ching-shan and Chiang-ling districts in the province of Hupeh. When struck they are said still to produce musical notes, their tones being true and melodious.

Wên-wu 1972. No.1 Pl. 8.

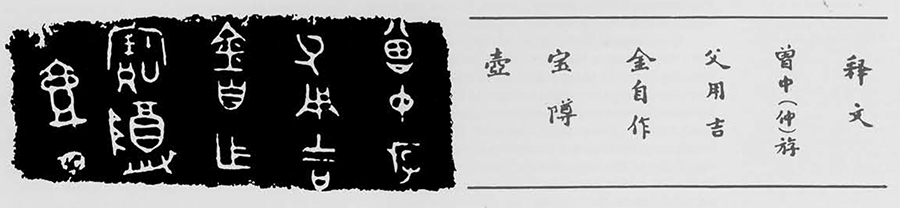

The discovery of the coins shown in Fig. 4 is especially interesting for numismatics. “Ying yua” coins are already mentioned in the literature of the Han period and single coins of this denomination have in recent years been discovered in Kiangsu and provinces; some are now on exhibition in the Nanking Museum. Much more often than actual coins, imitations in clay were placed in tombs by people of the State of Ch’u. These elegant gold coins are very different from the much cruder bronze spade or knife coins used in the northern part of China at that time.

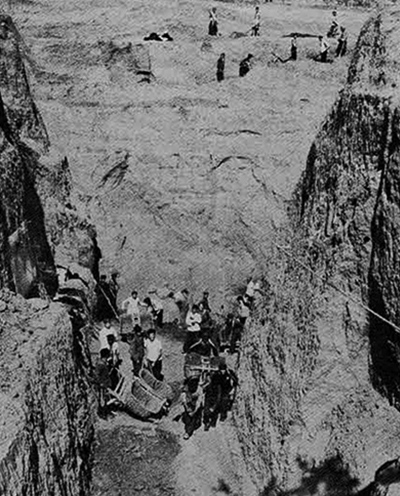

To be counted among one of the most memorable excavations of the world are two large cliff tombs discovered in 1968 by members of the People’s Army of Liberation. They were cut deep into the Ling-shan mountains (foothills of the Taihang range), west of Mancheng in the province of Hopei. These mountains are barren of trees, and piles of hand-chipped rocks on the slopes aroused the curiosity of the soldiers and led to the discovery of the first tomb. Similar topographical features nearby led a month later to the discovery of the second tomb (Figs. 5 and 6). The entrances to both tombs had been so tightly sealed by rocks and brick walls covered with molten iron that opening them proved extremely difficult and finally some dynamite had to be use The dimensions of the two tombs can only be described as “royal.” The layout follows, in general, a type well established in the Western Han period. What may surprise many people is the so-called “bathroom” in the recess off the coffin chambers in both tombs. However, from the Shang period onwards pottery or bronze washbasins have been a very common tomb gift; cleanliness as a sign of purification is a very ancient concept and as demonstrated here extends beyond the grave. Even more surprising, a stone tomb built in the 2nd century A.D. in Pai-chai near Yinan in Shantung, excavated in 1954, contained a privy behind a partition wall in one of the side chambers, complete with two footstands and a cesspool.

Inscriptions on objects, seals,and historical factors leave no doubt that the tombs are those Liu Sheng, King of Chung-shan (Fig. 5) and his queen Tou-wan (Fig. 6). Liu Sheng was the ninth son of Emperor Ching (ruled 156-140 B.C.). His mother was Madame Chia, a concubine of the Emperor. Liu Sheng was made King of Chungshan by his father in 154 B.C. His capital, situate south of Mancheng, was Chung-shan, now called\ Cheng-ting. It was a principality and for this reason Liu Sheng is sometimes called Prince not King. Tou-wan was the grand-niece of Empress Dowager Tou, the mother of Emperor Ching. We know that Liu Sheng died after 42 years of rule it 113 B.C. The date of the queen’s death is not recorded but an inscription on a seal found in he tomb: “Chung-shan tzu-szu,” a title abolished in 104 B.C. and replaced by “Chung-shan miao tzu, suggests that she must have died before that date.

Wên-wu 1972. No. 1. Pl. 1.

Kaogu 1972. No.1. Pl. V, 1.

The oil basin is suspended from the beak of a bird and in the other one basin is placed on the head and one on the back of a resting ram. Most intriguing is a kind of traveller’s lamp with the basin folding into a cylinder when not in use. However, a great surprise was the lamp shown ii Fig. 8. It is of great beauty as well as technical ingenuity. Inscriptions repeated several times or this lamp allow us to reconstruct its history. According to one it once belonged to the Yang Hsing family. This means that it could not have been made before 179 B.C. when Liu Chieh was first made marquis of Yang Hsing by Emperor Wen. However, another inscription informs us that it was in the Ch’ang Hsin Palace (Palace of Eternal Fidelity) belonging to the Empress Dowager Tou, and stood under the care of the Office for Cleaning. It is not recorded how it got therE However, it is most likely that it was confiscated when, according to the Shih-chi, in 151 B.C. Emperor Ching removed the eldest son of the marqi. of Yang Hsing as heir because he had committed a crime; thus it seems more than likely that he gave the lamp to his mother who, in turn, presented it to her niece Tou-wan, perhaps as a wedding present.

According to one description in a more popular journal, the greenish stones inset in the vessel (Fig. 9) were turquoise; however, the design on them makes that very doubtful and in the latest report in Kaogu they are referred to merely as “inset stones.” This vessel is again rather unusual in style, certainly more nearly akin to the late third or beginning of the second century B.0 than to the latter part of that century. Among other wine vessels of the same type (hu) may be mentioned a particularly large one (height, 59 cm.) beautifully inlaid with gold and silver and with a lid resembling in shape the one in Fig. 9. Accord ing to an inscription it was originally made for the palace of the King of Ch’u, a member of the Liu family, in the Western Han period. This proves that it must have been cast before 154 B.C. because the King of Ch’u was among the rulers of seven kingdoms who revolted against the Emperor but were defeated and beheaded in the spring of that year. It appears that emperors in ancient China acquired their treasures by requisi tioning or as war loot in much the same way as those in Europe at a much later age. Two other bronze vessels were inlaid with gold in an intricate pattern interspersed with characters in niao chuan “bird script,” a decorative type very popular in the Warring States period, especially in the State of Ch’u. In general, the discovery of these vessels in a Western Han tomb demands a re-evaluation of dates of many bronze vessels in our collections hitherto assigned to the Warring States period.

The Po-shan-lu (Fig. 10) is another unsurpassed masterpiece of beauty and craftsmanship. It may be the work of Ting Huan, a craftsman famous for the beauty of his Po-shan-lu’s rising in nine mountain ranges. He is believed to have resided in Ch’ang-an during the Han dynasty. The high quality of this incense burner suggests that he lived in the second century B.C. Another incense burner in the tombs was a tripod with holes in its cover and in the bottom for the smoke to rise and the ashes to fall on the tray below.

Kaogu 1972. No. 1 Pl. 4.

Unfortunately most of the lacquer boxes placed in the tombs were severely damaged though inscriptions on some fragments could still be read. Some of the objects discovered in these tombs allow us glimpses of the life inside the palace. Games have always been a favorite pastime in China and in Tou-wan’s tomb were found well used coin-like bronze pieces with numbers and inscriptions apparently used together with dice. How it was played we don’t know; each piece contained a kind of message such as “the sage will assist” or “will become an excellent scholar.” Among the chariots in the queen’s tomb was a small one with skeletons of two ponies. According to the Hou Han Shy it was the custom for the Empress and the ladies of the palace to ride in small chariots drawn by ponies through the grounds of the palace. It speaks for health supervision that one of the bronze bowls, according to its inscription, was reserved for medical uses. A jar (hu) with various tubes for letting water drip through seems to have been a clepsydra.

In general, the time of Emperor Ching was one of peace and growing wealth causing luxury and extravagances in high circles, a trend which was reversed only in the later part of the rule of his successor, Emperor Wu (140-86 B.C.). The obvious delight of the King of Chung-shan and his queen in beautiful objects and a leisurely way of life was most probably instilled in their early days at the Imperial Court at Ch’ang-an. They may well have been influenced, in particular, by the Empress Dowager Tou, who was a very dominant personality, an ardent Taoist, follower of Laotzu and the Yellow Emperor, and opposed to the rational ethic of Confucius. The philosophy underlying Taoism values highly inborn vitality and spontaneity and provides a strong stimulus for artistic creativity and enjoyment of life.

The strange and rigid look of the figures on the pottery set (Fig. 11), discovered in a much simpler tomb of the Western Han period, suggests that they do not imitate a performance with live human actors. There is ample evidence that the craftsmen of the Western Han period could make their pottery figurines look very much alive and their movements lifelike. My conjecture is that this pottery set imitates one made in a different material, most likely wood, which would account for the peculiar stiffness of the figures. It seems likely that the whole set was a replica of a k’uei-lei play, sometimes translated as “puppet play.” They are well known to have been performed especially at the time of mourning or at funerals.We know that in such plays mechanical figures were used that could be made to perform. In this case it would mean that, for example, the drummer would beat his drum, the dancer rotate or wave her sleeves, the acrobats somersault. The importance of acrobats, dancers and musicians on such occasions is supported by many pictures on walls of tombs of the Han period. That mechanical toys of this type are not beyond the technical ingenuity of the craftsmen of that time is well attested in literature. For instance, according to the Hsi-ching tsa-chi, when Kao-tsu, the first emperor of the Han dynasty, entered the palace of the last Emperor of Ch’in he found among other objects twelve rather large (about 69 cm. high) bronze figures of seated men arranged on a mat, each holding a lute or reed organ, all wearing colored silk clothes exactly like those worn by living people. They were made to make music by two people: one operating a rope running through a tube, thus setting into motion the actual movements of the musicians; the other blowing into a tube causing the music to sound. However, the performers on our set could have been moved by different methods; the simplest would be by pulling strings.

Wên-wu 1972. No. 1. Pl, 11.

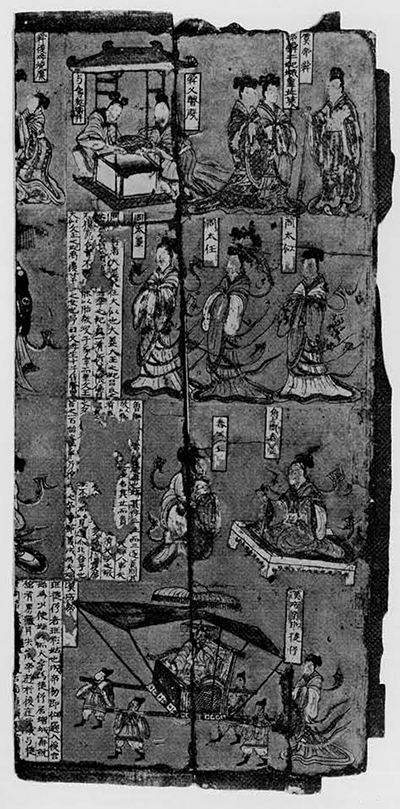

The tomb containing the sculptured stone pillar bases (Fig. 12) and the painted wooden screen panel (Fig. 13) was a rather large one (over 17 m. long) consisting of tomb-way, front, rear and one side chamber. It was built of large bricks, some not only adorned with patterns on one side but with an inscription on the other: “Lang yeh-wang (title) Ssu-ma Chin-lung’s longevity bricks,” a unique feature so far not encountered in any other tomb. According to this inscription and a tomb record the tomb was that of Ssu-ma Chin-lung, a powerful man who at one time had been a general and at another held a high position in the government of the Northern Wei dynasty. He died A.D. 484. Thieves a long time ago had entered the tomb through the ceiling but it still contained 454 objects, among them a great number of partly painted pottery figurines of men, women, warriors, men on horseback and animals; some different in style from the more common Six Dynasties type of pottery figurines. Among house hold utensils were a spittoon and some vases covered with a light bluish-green glaze. The wooden coffin had decayed but the large stone table on which it had been placed was decorated with beautiful carved relief similar in style to the pillar bases; most probably both were made by the same man or came out of the same workshop At the time of Ssu-ma Chin-lung’s death Tatung was still the capital of the Northern Wei dynasty. The subjects painted on the five wooden screens (Fig. 13) must all have been the stock-in-trade, not only of story tellers and small theatrical groups but also of the pictorial artists. Some of the scenes on these panels are included in the famous Ku K’ai-shih (ca. A.D. 345-405) scroll “The. Admonition of the Instructress,” now in the British Museum. The difference between the pictures on the scroll and those on the screen lies in their quality, Ku K’ai-shih being a genius and the painter of the screen a competent but somewhat dry artist. The question which we may ask is: did he know Ku K’ai-shih’s work or did both, in general arrangement and in the selection of scenes from a particular story, follow models well established in the 4th and 5th centuries A.D.? However, the pictures on the screens are perhaps slightly superior to paintings in Tun-huang like those in the Ping-ling-ssu cave dated A.D. 420.

Wên-wu 1972. No. 3.

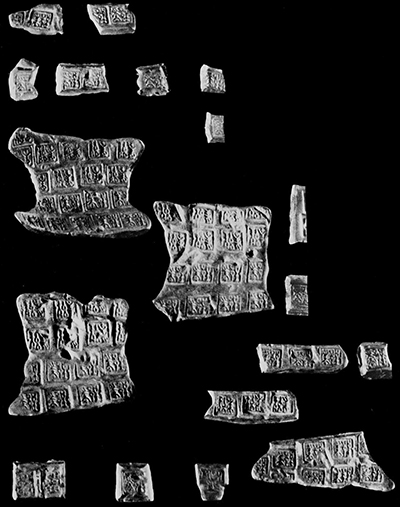

Since 1949 many remnants of textiles have been discovered along the ancient silk road leading from Kansu through Sinkiang, the Uighur Autonomous Region, to the West. Since 1966 an overwhelming wealth of new material has come to light among other places in Astana, in the Turfan basin in cemeteries used during the Sui and T’ang periods. Included are pieces of plain silk, multicolored damasks, brocades, and embroideries as well as simple tie-and-dye and batik-dyed silks. Among the textiles dating from the T’ang period are a number of fabrics patterned with animals facing each other in Sassanian style in a dotted circle. In many cases the tombs contained dated inscriptions (Fig. 14) valuable for studies of stylistic and technical development. Some particularly elaborately figured polychrome silk in mature T’ang style shows Western influence insofar as the Chinese method of warp-patterning was replaced by weft patterning. On a silk brocade dating from the early 7th century animals were placed in single compartments similar to those on bronze mirrors of the Sui and early T’ang periods. The custom in these regions was not only to put textiles in the tombs but to bury the persons with their clothes. This gives us the opportunity to study changing fashions. Among the many excellently preserved slippers dating from many periods, ma be mentioned one made of silk brocade with rounded toes reflecting the fashion of the Eastern Tsin period (A.D. 317-420). It was patterned with flowers, animals and an inscription. The one in Fig. 14 shows the fashion worn in China proper in the Sui and early part of the T’ang period, while another one made of hemp with a plain but very high upturned toe resembles those of pottery figurines dating from the middle of the T’ang period onwards. Another surprising find is the embroidery discovered in Tun-huang (Fig. 15). Embroideries like these were used as wall hangings at special festivals in Buddhist temples and monasteries as well as in the Buddhist caves in Tun-huang. They are mentioned in contemporary literature but this is the first one which survived at least in part in reasonably good condition. Those who embroidered or donated them hoped thereby to acquire “merit” in the Buddhist sense, valuable for life in the beyond and for future life-cycles.

In addition to textiles many written documents survived in the dry climate of the Turfan region, among them a long scroll with a handwritten copy of the Lun-yu, the Confucian Analects, with a commentary by a famous Han scholar. It was dated A.D. 710 and is thus the earliest extant copy of this Chinese classic.

Wên-wu 1972 No. 3.

In 1970 in Hou-chia-ts’un, a southern suburb of Sian in Shensi, two large pottery jars were discovered containing a hoard of over a thousand objects. Sian is the site of ancient Ch’ang-an, and since 1949 extensive excavations and research on the layout of the city and the situation of its palaces and temples have made possible the identification of the site in which the hoard was found as situated in the Hsing-ho ward of Ch’ang-an during the T’ang period (the exact place where in the 8th century had stood the palace of Li Shou-li, Prince of Pin, a cousin of Emperor Hsuan Tsung who ruled A.D. 713-756). After the death of the Prince of Pin in A.D. 642 his son resided in the palace. The hoard included 260 objects made of gold and silver; alone among the containers used for food were three bowls made of pure gold and 114 made of silver, including a variety of bowls, plates, and boxes in all sizes. Those for beverages included four cups and one vessel for warming wine made of gold and about a dozen winged cups, pitchers, ewers, and so forth made of silver. The hoard also comprised bowls made of precious stones such as jade, agate, rock crystal and a drinking horn of onyx (Fig. 18). A number of silver boxes were reserved, according to their inscriptions, for pharmaceutical uses, while the content of others, such as powdered gold, cinnabar, coral, quartz, indicated that some members of the household were engaged in alchemy and the production of the pill of longevity or immortality—the so-called hsien cult.

Although the hoard contained some silver hairpins, bangles, and a few small golden figures of running dragons, they can hardly be considered as representative of the jewelry belonging to this kind of family; they look more like odds and ends. We may thus draw the conclusion that the female members of the household were either not asked or not willing to have their possessions included in the hoard. A number of silver locks, some inlaid with gold, were most probably those of boxes in which the treasures had been kept.

The objects in this hoard are representative not only of the wealth of this family but, in general, of the luxury style of life, the extravagant and the exquisite taste of the ruling classes living in Ch’ang-an, the capital, at this time. There are hardly two cups or bowls quite alike in shape and decoration. The creative imagination and the craftsmanship of the artist are unsurpassed. For example, each petal of a golden lotus bowl was engraved with a variety of flowers, birds and animals; also, the gilded and embossed center decoration was different on each of a number of six- or eight-lobed plates and one in peach-shape. In fact, the motifs on the golden and silver objects include all the well-known T’ang dynasty types from floral sprays, acanthus, scrolls, to fishes, birds, animals, hunting scenes. The techniques employed range from engraving, tracing, gilding, granulation to inlay with gold, silver or precious stones, filigree, openwork, embossing.

Although quite a considerable number of cups and bowls made of silver have survived from the T’ang period, the opposite is true in regard to objects made of pure gold. The gold cup in Fig. 16 is of double importance because of its unusual decoration. The so-called cox-comb vessel (Fig. 17) is notable for two reasons. First, such vessels are most commonly dated post-T’ang because in recent years quite a number of pottery vessels in this shape have been discovered in tombs of the Liao dynasty, that is, of the Khitans who ruled over Manchuria and part of Northern China from A.D. 907 to 1119. The discovery of this vessel proves that the shape had been popular in China much earlier. Secondly, it is notable because of its decoration; the strange horse depicts one of Emperor Hsuan Tsung’s famous dancing horses. According to the Minghuang tsa-lu, the Emperor considered these horses so valuable that each was given a spacious hail of its own and a number of grooms were assigned to look after each one. They were outfitted with embroideries and their manes studded with ornaments in gold and silver. During great festivals, and especially at the birthday of the Emperor, horses danced to the accompaniment of an orchestra and their performance included rotating with wine cups in their mouths exactly as shown on the pitcher. Later, when the halcyon days had passed, these horses are said to have been used as battle chargers. One day hearing the strains of music, they promptly broke rank and began to dance. The cavalrymen thinking they had gone mad killed them all.

Wên-wu 1972 No. 3.

The rhyton and a number of coins are good examples of Ch’ang-an’s cultural exchange with other countries and her cosmopolitan role as one of the great capitals of the world during the T’ang dynasty’s rule. Contact was especially close with the West and with Japan: among the foreign coins were a Sassanian silver coin (Chosroes II, A.D. 590-627, a Byzantine gold coin (Heraclius, A.D. 610-641) and five Japanese silver coins (Wadokaiho, minted A.D. 708). Predominant among the Chinese coins were gold and silver pieces of different denominations inscribed with the cyclical date k’ai-yuan (A.D. 713-742). According to its inscription a silver disc was issued by the Chien-an district in the 19th year of k’ai-yuan, that is A.D. 731. The hoard also contained ancient Chinese coins dating from the Warring States, Han and Six Dynasties periods. According to their inscriptions some silver tablets of different sizes were weights for a scale. They are important because they allow us to establish correctly the exact standard weights used in the T’ang period.

The objects in this hoard correspond in style to that of the mature Tang time, the 8th century A.D. and the fact that none of the coins date later than A.D.642 limits the time to the first half of that century. This provides us with the explanation why and when the hoard was buried. In A.D. 756 the army of the rebel An Lu-shan attacked the capital, forcing the Emperor and his court to flee to Szechuan. It is more than likely that the Prince of Pin accompanied him. Before setting out on the perilous journey, anticipating the looting of the capital by the invading soldiers, he buried his treasures. Apparently he never returned to retrieve them.

The time of Hsuan Tsung’s rule was one of the great periods of China, the court in Ch’ang-an perhaps the most sumptuous of all times. The Emperor himself is known as a patron of the arts, especially the performing arts. In his younger days he had been an ardent Confucianist, very economically minded and adverse to all luxuries. When he got older he changed, he moved his court from Lo-yang to Ch’ang-an in A.D. 736, his mind opened to the pleasures of life and beauty, more and more he came under the influence of Taoists and is even known to have written a commentary to the Tao-te-ching. The high stage art reached at this time is due to the juncture of Buddhist and Taoist ideas. Buddhism had given the artist the task of expressing in his work the divine in human shape while in Taoism the creation of beauty was conceived as expression of harmony between the two powers of yin and yang, heaven and earth, therefore the reflection of a mystical reality imbued with life-giving powers. It is possible that most of the exquisite objects in this hoard were created in a relatively short time, the first half of the 8th century, with the highest point reached between A.D. 736 when the Emperor moved to Ch’ang-an and the last years before A.D. 756. Silver plates with gilded embossed centers, very similar to those in this hoard and obviously made in the same workshop, were found in Sian in 1956 together with silver bars inscribed with the cyclical dates kai-yuan and t’ien-pao (A.D. 742-756).

According to the T’ung-chien kuang-mu (by Ssu ma Kuang, 11th century) soon after Emperor Yang Ti of the Sui dynasty moved his capital from Ch’ang-an to Lo-yang in A.D. 605 he started to build large granaries. One built about 4 km. east of Lo-yang was said to have contained about 300 storage pits. It was later taken over by the T’ang dynasty and perhaps enlarged. The site of this granary was discovered and excavated between 1969 and 1970 and, as so often happens, archaeological discoveries confirmed the accuracy of Chinese historical reports. The granary was placed in a walled-in area covering 420,000 square meters. It contained about 400 small and large subterranean or half subterranean round storage pits laid out in symmetrical rows. Each was constructed in such a way that air could circulate, thus preventing the grain from getting moldy. Each storehouse had bricks with inscriptions specifying its location in the granary, the quantity of grain stored, the year and month it had been delivered and the status and name of the storekeeper. Altogether it is another example of the organization and working of the bureaucratic administration of ancient China.

In a number of provinces (e.g. Anhwei, Shantung, Hopei and Chekiang) some pagodas have been examined and foundations excavated. According to inscriptions most were built in the 10th and 11th centuries, that is during the Sung dynasty.

A considerable amount of archaeological work since 1949 has been directed towards an exploration of the layout of ancient cities, palaces, temples and various architectural features. In recent years in Peking the necessity for new constructions led to the discovery of the remains of Tatu, the capital of the Yuan dynasty (AD. 1279-1368). Investigations have so far advanced that the size, walls, gates, pattern of streets, situation of palaces and temples as well as details of its water supply and drainage system can be reconstructed 29 Besides these, interesting Eastern Chou or early Han types of pottery wells have been found. In 1969 was discovered the western side of the barbican entrance to the ancient Ho-yi gate (Fig. 19). The date scribbled on its wall tells the story of its building. At that time rebellion against the Mongol rulers (Yuan dynasty) was in full swing and in A.D. 1358 Liu Fu-t’ung and his army threatened Tatu. Tatu was at that time without adequate defense forces and the frightened Emperor Shun-ti ordered that immediately barbicans be built for all eleven city gates. Incidentally, the attack never materialized but the threat signalled the end of Mongol rule.

Kaogu 1972. No.1, Pl. 8.

Tombs of two princes belonging to the Imperial family of the Ming dynasty were excavated in 1969 and 1970/71. One in Cheng-tu in Szechuan proved to be that of Ch’u Yueh-lien (13881409), eldest son of the Prince of Ch’u; the other, a cliff tomb at Chang-chai, Tsou-hsien district in Shantung, that of Ch’u Tan, the tenth son of the first emperor of the Ming dynasty (Fig. 20). The tomb in Cheng-tu had been robbed and only its impressive palace-like chambers were left, while Ch’u Tan’s was found completely undisturbed; it contained over a thousand objects including a great number of figurines, over 300 volumes of books, four scrolls of calligraphy, and a silk fan painted with hibiscus flowers and butterflies with an inscription by the Emperor Kao Tsung of the Southern Sung dynasty (A.D. 11071187). The excavation of this tomb proved extremely difficult because of landslides and the seepage of underground water from the chamber.

These are only a few examples of excavations since 1966. It will be some time till all the new discoveries can be properly evaluated, but it is already evident that this new material must be considered carefully by anyone working in the field of Chinese history, social or economic conditions, literature and art.