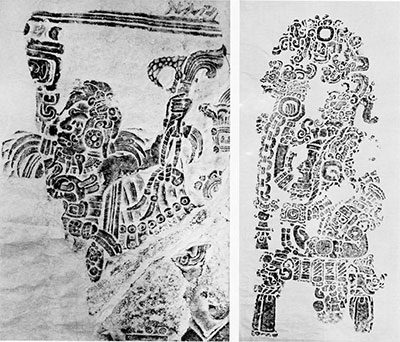

The predominantly monumental art of the ancient Maya civilization in Classic times, from the third to the tenth century A.D., produced close to a thousand known stelae. These monolithic, upright stone slabs, usually bearing hieroglyphic inscriptions and figures of personages, plus the bas-relief tablets in the temples, are the carvings from which I have been taking the rubbings now on exhibit at the University Museum.

Until recently, the stelae were generally though to be solely concerned with marking of time, the human figures being portraits of gods and priests. The dynastic hypothesis set forth by Tatiana Proskouriakoff, makes it seem likely that some, if not all, of the figures are the rulers and their families who are named in the inscriptions.

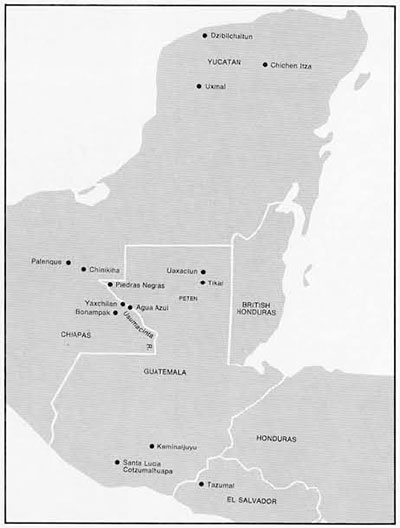

I wanted to record as many of these monuments as possible, accurately and in full scale, by a process of “rubbing.” The packet of documents from the Mexican and Guatemalan Governments and the many credentials which enabled me to do this became, for three years, my most essential, if not my most valuable possessions. Best represented are the Classic sites of Tikal, Kaminaljuyu, Santa Lucia Cotzumalhuapa, Tazumal, Palenque, Chinikiha, Yaxchilan, Conampak, Piedras Negras, Uaxactun, Chichen Itza, Uxmal, and Dzibilchaltun.

“Rubbing” is a very ancient Chinese method of recording. At times I have used a rather different technique in order to bring out the nature of the particular stone, and to pick up every cut of the original carved monument. There are different ways, or combinations of ways, to do this, depending upon type of stone, its moisture content, and the degree of humidity.

A hard black basalt monument from Kaminaljuyu calls for a different technique than the more porous limestone of Tikal, the moisture-laden bas-relief tablets at Palenque, or the lime-encrusted overhead lintels of the doorways at Yaxchilan or Bonampak.

I use Japanese handmade papers of different types and weights. An eight-foot stela with deep relief demands a paper of sufficient strength to withstand the stretch and pull caused by the deep cuts. A delicately lined tablet, such as that of the “Panel of the 96 Hieroglyphs” at Palenque, needs a fine-grained, yet strong paper to bring out the detail. Sometimes I would have to try many methods before finding the right combination. Such was the case when working on the “Full-figure Glyphs of the Palace Tablet” at Palenque, where the moisture content within the stone varied greatly in adjacent sections.

I cannot stress too strongly the two most important points that must be borne in mind at all times: 1) the original monument must not be marred in any way, and no pigment at all can be allowed to come in contact with the stone; and 2) the rubbing must be authentic, no embellishments, no 20th century additions or so-called improvements being allowed.

The paper is anchored against the stone with a few pieces of masking tape. Then, starting at the top, the paper is wet down, being pressed carefully into every little crevice of the stone with a wad of cheese-cloth. After I am sure that every line has registered, I wait for the paper to dry. This takes anywhere from a few seconds to all day, or even over night.

Working with an oil pigment to which is added a solution which prevents any paint from seeping through the paper, a very small amount is put on a sheet of aluminum and spread thinly around. Then with a six-inch square of fine China silk wrapped around my thumb, I begin the process of pressing my thumb, first to the aluminum and then to the stiffened paper. The tone is built up gradually from light to dark. For a very delicately carved stone, as many as one hundred applications per square inch are necessary. The pigment must be evenly spaced, with none getting into an area where there is no relief. By careful study of the monument before the process is started, it is possible to tell which areas to avoid. After all is dry, the paper come off in a rather rigid sheet which can be carefully rolled.

The other technique that I use is similar to the old Chinese method. The same kind of paper is used, but sumi ink is applied with small cotton balls covered with China silk, held tight with scotch tape. The process of putting the paper on the stone is the same, but applying the black must be started at exactly the right moment. It cannot begin until proper moisture content is indicated…when the paper has turned not quite (but almost) a dead white, or the dry color of the paper. The sumi ink is put on a stamp pad, spread around with a palette knife, and the stamper pressed gently against the pad, then against a piece of metal and finally to the paper.

In dealing with a stone which contains a great deal of moisture, or one that is in a humid tomb, it is impossible to use the sumi method. This technique also cannot be employed when working in direct sunlight, as the paper dries too rapidly.

Sometimes I use a combination of methods, being governed by moisture content deep within the stone or close to the surface, the kind of stone, its roughness or smoothness, its deep or shallow relief, the delicacy or forcefulness of its cuts, and current weather conditions such as rain, sunlight, and humidity. All of these things have to be dealt with at one time or another.

The paraphernalia necessary to do this on a large scale becomes so cumbersome that when I am going into a remote area, I usually take my equipment but leave clothes and food behind.

This has its interesting side too, as the time I had to stay in the same muddy pants for a week and had only one change of shirt, one always wet on me, the other hanging up wet, in the hope that it might dry out a little. By not taking food in with me, I’ve had all sorts of unusual food such as stewed monkey, iguana, roasted wild boar, birds, frogs, all kinds of fish, a delicious dish of broiled armadillo which we dipped into an excellent soup and ate with our fingers (this at Bonampak), paper-thin tortillas two feet in diameter, fried chilies (so hot that I had to swallow them whole between a fold of tortilla), and the ever-present coffee made with corn husks, a few coffee beans, and sugar-can molasses. This does not taste like coffee, but at the end of the day it is very good. And almost always there is the corn drink, atole, sometimes thick and sometimes thin, depending upon where you are.

Tikal, one of the largest and most spectacular Maya centers, was where I did my first rubbings. Stela 31 (A.D. 500), having 213 glyphs and three large personages, reflects a Mexican influence in the tlaloc signs. Its hieroglyphs are pure Maya. This most amazing monument was still situated deep within Temple 33 in the North Acropolis when I worked in the humid dark chamber until all four sides had been recorded.

Altar 5 at Tikal, with an encircling band of thirty-one glyphs, and associated Stela 16 presented even greater problems. Because of the size of the monuments and their location in direct sunlight, I used cloth sheets anchored down with stones and rope. Paper could not be used on the altar because it was too large for me to reach half way across and had I stepped or leaned on pressed-in paper, the relief would have disappeared. On the cloth, by carefully feeling my way, I could tell where to press the pigment next.

I have many fond memories of Tikal: its towering spectacular temples and palaces; the enthusiasm and dedication of everyone working there; the thrill of accomplishment when design elements, which at first had appeared indistinguishable, were finally picked up; long evenings spent sitting by the aguada discussing the mystery of Tikal with archaeologists who were dedicating their lives to this; climbing Temple II in full moonlight and listening to symphonies echo across the Great Plaza, being played on a tape recorder that some archaeologist had taken to the top of Temple I; nights in a chultun (underground chamber); climbing through the roof-comb of Temple V to view miles on end of jungle, through which penetrated the tops of the roofcombs of other Tikal temples; breakfast on a Sunday morning in the Village, where the hospitality couldn’t have been finer or the food better; racing in the jeep to meet the Aviateca plane; the thrill which came when someone made a new discovery. All of this spelled Tikal to me.

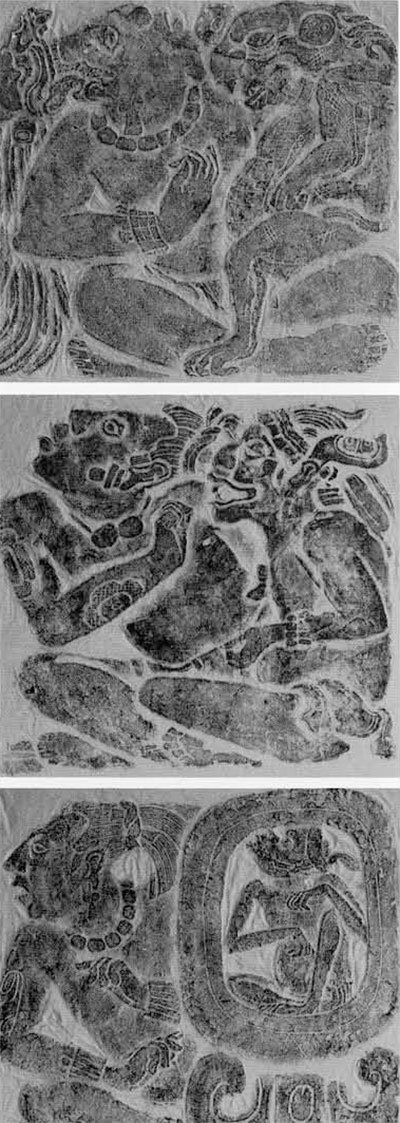

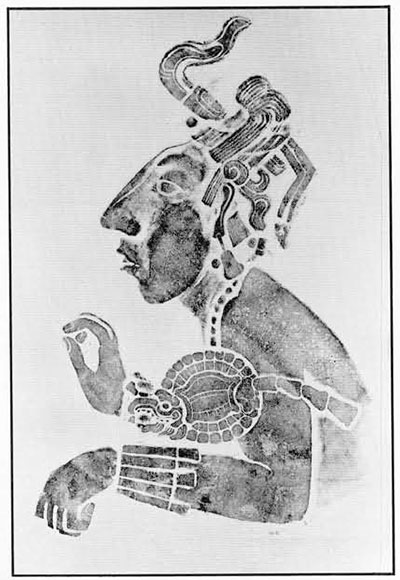

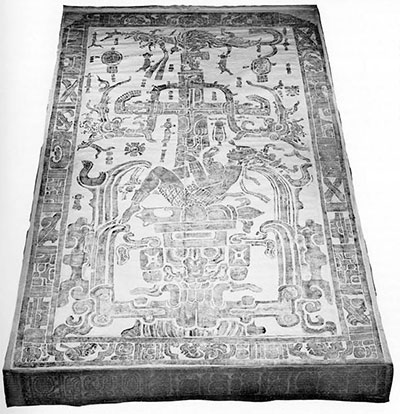

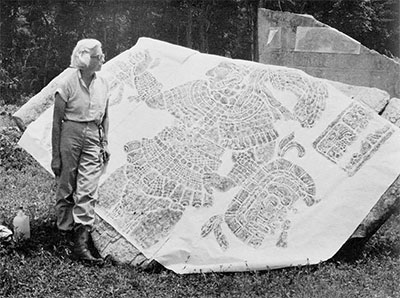

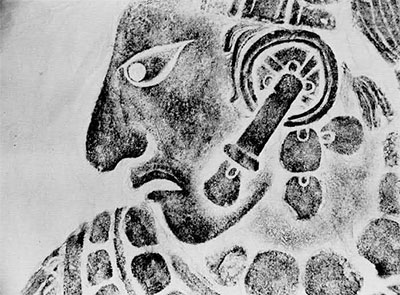

Probably the most exciting rubbing that I ever did, and also the hardest, (I lost ten pounds in three weeks) was the sarcophagus in the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque. In 1949 the Mexican archaeologist, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier, noticed what appeared to be finger-holes in a large floor slab in the inner room of one of the temples. The slab was raised, revealing a rubble-blocked stairway leading into the pyramid base. By 1952 the elaborate crypt itself was revealed. The sarcophagus lid, which is 12.5 feet x 7.25 feet and rests upon a coffin base about 10 x 7 x 3.5 feet, is in perfect condition. The sculptured sarcophagus is probably the most remarkable work of art yet uncovered in Mesoamerica.

In the center, a life-size royal personage reclines, dressed in an ex (breechclout) of tubular jade beads, anklets and belt of jade beads, and a necklace in the form of a turtle. This young man is reclining in the “earth symbol,” denoting life and re-birth. The cross, so often found at Palenque, rises from the center of the figure, and has the two-headed serpent wrapped around it, with the arms of the cross ending in stylized serpent heads. On the border are hieroglyphs of the sun, moon, and Venus, and depictions of human heads. The four sides of the coffin are also carved, with the earth-symbol carrying all the way around. From this symbol emerge the heads and torsos of personages with elaborate headdresses.

I made about 220 square feet of completed rubbings, not counting all of those that had to be re-done, of the entire sarcophagus.

Twice a day, I went through the same procedure: climbing to the top of the 70-foot Temple of the Inscriptions, crawling down the 76 steps inside the pyramid base leading to the locked grill at the entrance to the tomb, having the guard who came down with me unlock the grill and then lock it behind me, lowering myself five feet to the lower level and hoisting myself by my arms to the top of the sarcophagus. Each time I had to carry paper, water, flashlight, and lantern. The rest of the equipment was kept in the tomb until the completion of the project.

As the public is not allowed inside the crypt, this locking-in procedure went on daily. In order to leave, I had to wait for a guard to come down and unlock the grill. Twice my lantern ran out of fuel and I sat for two hours in total darkness, accompanied only by the nine gods of the Maya underworld, who were modeled in deep relief all around the walls of the tomb.

The sarcophagus lid was very difficult to work on, as everything had to be done at exactly the right moment. The stone had to absorb all the moisture from the paper, but the pigment had to be applied before the paper absorbed moisture from the humid air. The humidity problem was aggravated by the heat generated by the Coleman lantern.

Working on the sides of the crypt was even worse, as all the time I had to stand in a foot of limestone water, which over the centuries had seeped into the tomb. The west side was the most difficult, as there were only twelve inches between the sarcophagus and the wall of the tomb chamber. Carvings on this side had never before been accurately recorded, for space does not permit photographs to be taken of it. I had to work side-ways, edging myself along the muddy wall, in order to do this section. I would come out of the tomb completely soaked and covered from head to toe with wet, white lime plaster. My one frightening encounter with a fer-de-lance came when I was staying alone at the Palenque ruins. I arose one Sunday morning and there was a three-meter fer-de-lance coiled over the doorway to the hall. He had been there all night with me, but when I first saw him in the twilight, I had thought that he was a coiled wire. All of my calling for one of the workmen was to no avail. No one was around. I stood in the outside doorway for one whole hour, with one eye on the serpent and the other on the trail, until finally Augustin, who had lived at the ruins for thirty years, came along. With a forked stick and a club, he made fast work out of the fer-de-lance. The next morning, workmen were chopping down all of the grass around our building with machetes. They kept it that way all summer.

The week spent at Yaxchilan was not nearly enough. I marvel that Maudsley, in the late 1800’s and Teobert Maler, ten years later, managed to accomplish all that they did there. In the intervening years, the jungle has grown back to its original state–impenetrable.

To get to Yaxchilan down the Usumacinta River from Agua Azul took five hours in cayuco (dugout) in pouring rain. Everything was wet except my paper, which was encased in a plastic container. The river was high, muddy, and swift, full of rapids and whirl-pools. In between deluges of rain, as many as twenty guacamayas, the magnificent red, yellow, and blue macaws, would fly from a single towering ceiba tree, turning the sky into an incredible display of color. The scenery was unbelievably beautiful.

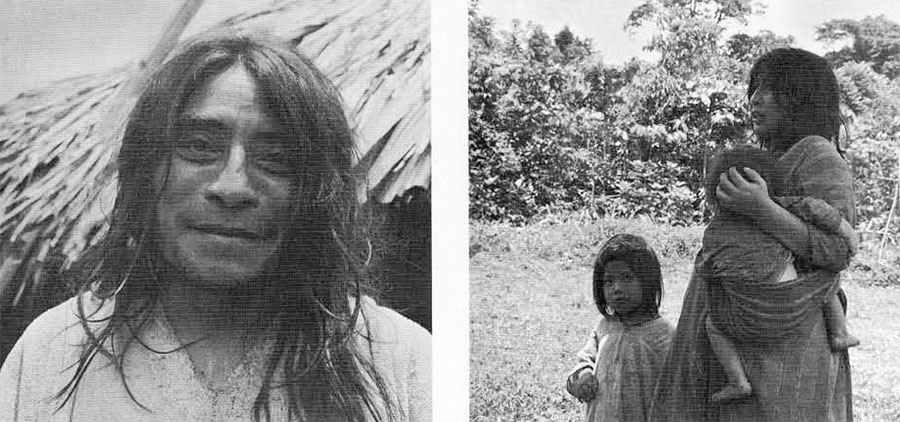

You cannot see Yaxchilan from the river, but by the time we had climbed out of the cayuco and up the steep muddy bank, Miguel de la Cruz, the keeper of the ruins, was emerging with his family from their typical Maya thatched-roof dwelling.

Our hammocks were slung up in a corral, and then to celebrate our arrival, a hog was slaughtered (this right in front of their main door). By afternoon we were eating pig cracklin’s and for supper had delicious stewed pork and rice. I soon became used to drinking the muddy river-water coffee, into which I dropped a double dose of halozone tablets.

Rain was so heavy that I started at daybreak for the temples with either Miguel or one of his sons, and would spend probably two hours cleaning mud and moss from a stela, finally getting the paper pressed in, when no warning at all, it would start pouring rain, spoiling everything. The river water was too dirty to use on rubbings, so fo these and for drinking, I chopped two or three inch diameter lanai water-vines, which contained plenty of good, clear water.

One morning, while walking along the trail I came upon a “wild boar” right in front of me making horrible noises, and mot about to let me go further I retreated cautiously, all the time expecting to be attacked. Miguel returned with me and we saw this “sow” giving birth ti a kutter if piglets.

On this trip, I had only one partial bath in the Usumacinta as just when I was half in the water, I saw two alligators only a short distance away from me. That was enough. I decided that I didn’t mind being dirty after all.

We were supposed to go to Piedras Negras on this same trip, but the guide finally admitted that the reason he couldn’t make the trip was that when, (not if) the cayuco overturned in the rapids, no matter how well we were tied in, either some of the equipment or one of us was bound to get lost. I reluctantly let him have his way.

I hated to leave Yaxchilan, even if I did see more snakes than I’ve ever seen in my life, outside the reptile house in the zoo. I also saw more beautiful birds. The trip back to Agua Azul took seven hours in the blazing sun. As it was not possible to shift positions in the narrow craft, I was burned to a crisp. We fished on the way, and I caught what I thought was a beauty, until I saw the fish that a ten-year-old boy caught just as we pulled in to Agua Azul, that was bigger than he.

One time on the flight back from Bonampak, a thunder storm came up, and although we made it over the mountains, visibility was practically nil. In order to land at Palenque, it was necessary to make the turn to land against the wind. After two tries, each time with the wind catching the wing and nearly flipping us over, we gave up. We flew into Tenosique, where we made a safe landing and two hours later took the slow rapido (train) back to Palenque.

The closest I’ve come to shaking hands with a jaguar was in the second trip to Bonampak. Doris Jason and Waldemar Sailor, two artists with whom I had done graduate work, and I had spent a sleepless night in our hammocks with mosquito nets. For hours we battled infinitesimally small chaquistes which got through the netting and up our pants legs and shirt sleeves, making us miserable. By 3:30 a.m. we could stand it no longer, so got up and sat huddled on boxes, with one candle, blowing cigarette smoke at one another. At daybreak, the chaquistes disappeared, but Doris was one mass of red sores over her body.

We were going up to Stela I and Wally was ahead of us on the trail. When Doris, Don Pedro, and I caught up with him, he was standing perfectly still and as white as a sheet. A jaguar (probably as frightened as we were) was twelve feet away, peering out of the bushes. We had seen its tracks in the mud every morning, but it was unusual for it to be there in daylight. “She” was killed the next week by a young man who brought her few-days-old cub back to Palenque. The “tigre” cub would sit in the middle of the table, drinking milk out of a doll bottle, while we ate dinner.

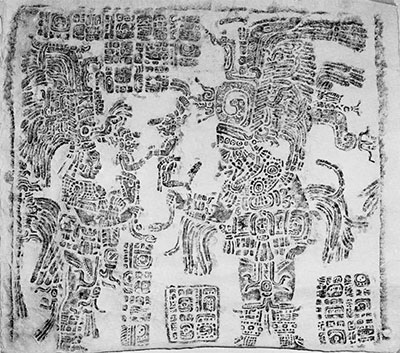

This episode however, put a stop to my lone walks back to the main plaza in the moonlight, where I used to stand and look silently at the remains of Bonampak, marveling at the elite Maya group who lived in this jewel of a site. Here in the Temple of the Frescoes (A.D. 710), are the murals, finest in all Mesoamerica, preserved by the formation of a heavy coat of stalactitic limestone, which is a result of constant seepage water for more than a thousand years.

As I stood there at night, I could see Stela I, now broken and veering to an angle, standing tall in the center of the plaza (A.D. 692-810). Its forceful countenance, modeled in bold outline, seemed to look down on me in the moonlight which accentuated the shadows of the deep undercut eye.

Life at Bonampak was wonderful, and Don Pedro made it so. He took us on mules over trails where we could see no trails, while he cut the way through with his machete. We spent one whole day on the beautiful Lacanha River. One shrill whistle, and a Lacondon Indian appeared from nowhere with a small cayuco for us. Don Pedro pointed out the edible plants and berries, the poisonous ones, and those used for medicinal purposes. With one blow of his machete he felled palm trees, which contained ten inches of delicious palm heart. It must be eaten immediately because as little as half an hour later, it begins to get tough and loses its flavor.

There are still many Maya areas where I hope to do more recording of monuments, and I look forward to the time when I will be able to go back. Now I would like to acknowledge my deep appreciation to Dr. Robert L. Rands and to Dr. E. Wyllys Andrews for their help in the research on the monuments from which these rubbings were taken, and for the knowledge gained by many discussions on Maya art; to Dr. Patrick Culbert, Peter Harrison, and Chris Jones for the help and interest shown me at Tikal; and to MArio and Amelia Leon Tovilla at Palenque for their help and cooperation, especially in working on the Inscription Tomb.