Connecting the Present to the Past

Silent Objects Speak to Naskapi Visitors

By Louisa Shepard

THE AMERICAN SECTION collection is the largest in the Penn Museum, numbering about 300,000 archaeological and ethnographic objects from North, Central, and South America. Many pieces made and used by Indigenous peoples were brought to Philadelphia in the early 20th century by anthropologists on collecting trips for the Museum. For over a century, the American Section has hosted cultural specialists, artists, and scholars from Native American and First Nations communities, collaborated with Native experts on curatorial projects, and strengthened its collections by commissioning and purchasing work from Native artists and craftspeople.

Penn Anthropology professor Dr. Margaret Bruchac, who teaches a Museum Anthropology course focused on this collection, involves her students in the effort to connect objects to Native communities. She examines material details, cultural markers, and narratives, asking: “How can we listen to the stories painted into seemingly silent objects, consider the knowledges embedded here that could yet be recovered, the songs that could be reanimated, the relationships that could be restored?” In 2018, she and her undergraduate student Ben Kelser wrote a blog post about a caribou hide child’s coat and cap attributed to the First Nations Naskapi people of Labrador and Quebec. The phrase “First Nations” describes Indigenous nations situated within the bounds of the Canadian nation-state.

The post caught the attention of Jill Goldberg, Director of Naskapi Liaison for the Central Quebec School Board, who decided to bring a group of students from Kawawachikamach, Quebec, to Philadelphia to see these objects in person: “This is about giving students a chance to reconnect with their story.” With funding from the Naskapi Education Committee, Goldberg, along with principal Joseph Whelan and assistant principal Shannon Uniam, brought all four students in the 2020 graduating class of Jimmy Sandy Memorial School to Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New York City early this year, with two days at the Penn Museum as the centerpiece of the experience.

Reconnecting with Ancestors

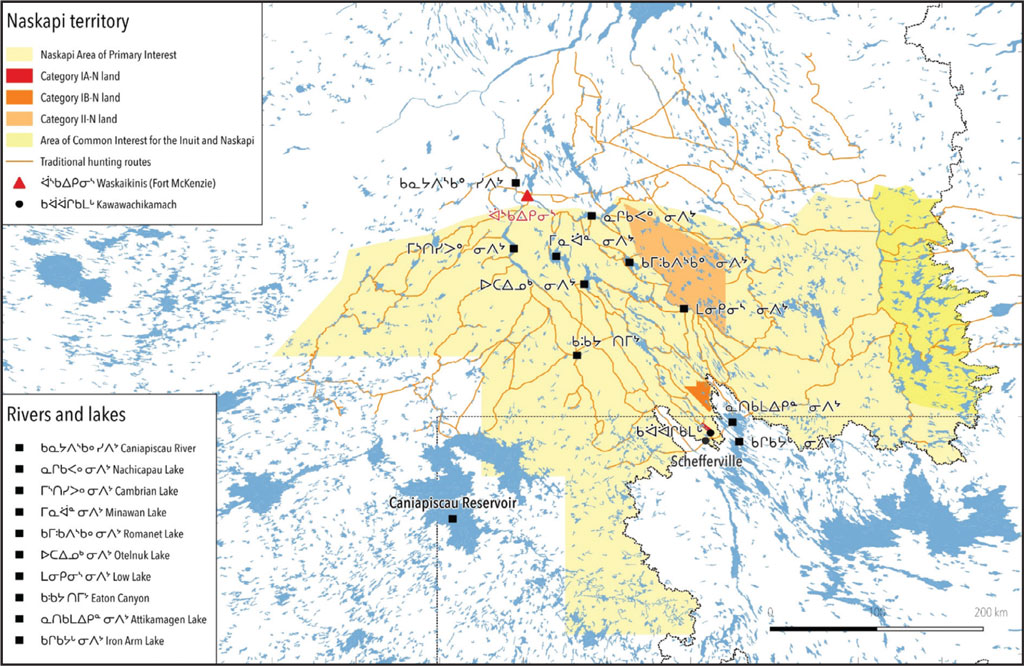

Shannon Uniam and her students are all Indigenous Naskapi, members of a First Nations band that has occupied sub-Arctic hunting territories for generations. Historically, the Naskapi and Innu people lived across present-day Quebec and Labrador. The combined pressures of European colonization and decline of the George River caribou herd eventually forced the Barren Ground band of Naskapi to settle on reserve lands near Schefferville in the 1970s. There is only one road to the community, and the area is surrounded by bodies of water. The trip to Philadelphia was the first outside the country for Uniam and her students.

At the Museum, the group’s primary interest was the Naskapi material collected by Frank Speck, one of the founders of Penn’s Department of Anthropology. As the group was escorted to a collections study room, Uniam looked through the window and gasped. More than 100 artifacts, made by her Naskapi ancestors nearly 100 years ago, were carefully laid out on a large table. It was the first time she had seen such a wide variety

of everyday items from her people, including hunting garments made of caribou hide painted with natural pigments, and the tools that created them.

“The first thing I thought about as I walked in was my grandfather, and the first thing I saw were the leggings. They were right there,” she said. “I was kind of shocked. I felt like my grandfather was there with me.”

Waking Up Silent Objects

The group met with several Museum staff, including Associate Curator and Sabloff Keeper of Collections Dr. Lucy Fowler Williams, who gave them a tour of the Native American Voices exhibition, and Bill Wierzbowski, Keeper of Collections in the American Section, who showed them behind-the-scenes storage of Native American objects. The visitors also learned about object conservation, the Museum Archives, and NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

But the main event was spending time with a large portion of the Naskapi collection. “These objects were silent, living dormant on shelves, observed by students or faculty now and then. But to have them with the descendants of the community who created them, literally wakes them up,” Bruchac said. “For me this work is not just research; it is about restorative relationships.”

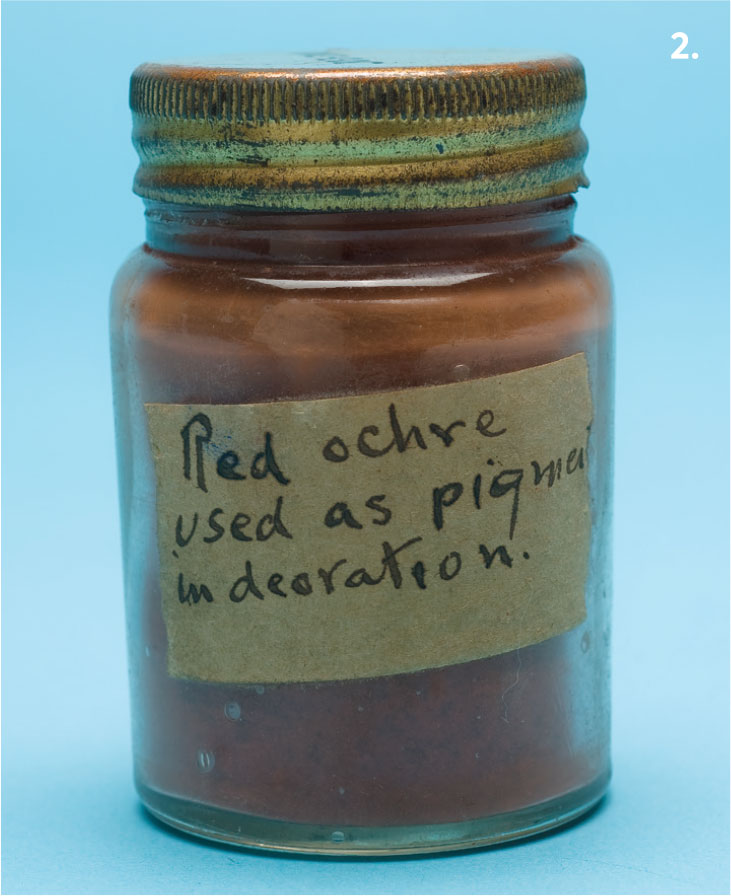

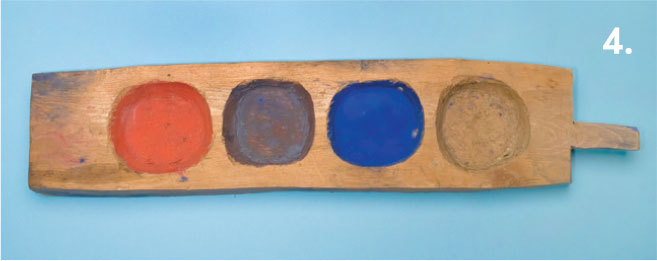

Frank Speck was known for collecting not just fine finished products but also well-worn coats and clothing and things from everyday life: wooden paint pots and pigments, tools and brushes, tobacco pipes and pouches, jewelry and games. Stephanie Mach, a doctoral student in Anthropology and Academic Engagement Coordinator at the Museum, selected a variety of those items for the visitors to see and touch during their visit, encouraging them to take pictures.

“Start by letting things speak to you,” Bruchac said to them. “You might even sense connections with the people who made them, in a way that isn’t always easy to explain.” The grandparents and great-grandparents of the visitors likely spoke with Speck, and it is quite possible that some of these objects were made or used by their ancestors. Gently picking up the hem of a coat, holding a moccasin, examining a wooden paint palette, for nearly two hours the visitors examined the dozens of objects. Mach helped Uniam pick up a thick winter hunting dress, with a fur-lined matching cape. “It’s so beautiful to see,” Uniam said as she held her arms out to measure the length of the sleeves.

The coat and cap described in the 2018 Museum blog post that prompted the visit were a favorite of student Laura-Louise Mameanskum. She explained her thoughts in the Naskapi language, translated into English by Uniam: “She can imagine what she saw like a young child, who is now an elder, or perhaps passed away. It could have been one of her relatives because she has a big family, really most of the community.”

The school has 250 students in the town of about 900 people. But none of these students had seen Naskapi items like these, except for a few in a display case at school. “I am proud and happy that we had a chance to see the artifacts,” Mameanskum said. A small black canoe is what spoke to student Seth Nabinacaboo because it reminded him of when he goes out canoeing with his family. For Rachel Nattawappio-Pien, the high moc- casins, or mukluks, reminded her of her grandmother. “She used to make stuff like that all the time,” she said, overcome with emotion. Uniam explained that her Inuit grandmother was well-known in the community for her handmade artisanal works.

Holding the mukluks was emotional for Uniam as well. “When I first saw those, I thought, ‘is this my ancestor’s?’” Her grandfather had told her a story about wearing similar leggings when he was a young boy going to hunt in the midwinter, trudging through muck and slush, desperate to find something to feed the family. “I can imagine what he went through, looking at those leggings,” she said. “So soaked, so cold, and he was so young.”

Her grandfather had also told her about a dream he had as a boy, not long after his parents died: he was lifted by an eagle, and when he looked down, he was wearing snowshoes. Uniam also wears snowshoes, often when she goes hunting. She asked Bruchac and Mach if they could see some snowshoes.

Mach led the group to banks of floor-to-ceiling cabinets. Pulling out one drawer after another, marveling at the Naskapi objects, they found two pairs of round snowshoes from the early 1900s to hold and examine

up close.

Carry It Forward

The experience was emotional for Bruchac as well, because so much of her research is directed at identifying and recovering Indigenous cultural heritage. She is especially interested in tracking collections she came to know through research for her book Savage Kin, which examines the relationships between Indigenous peoples and early 20th-century anthropologists, including Frank Speck.

She hopes the visit by the Naskapi is the beginning of a long-term relationship with that community and that perhaps they can help the Museum better understand the collection it is preserving. “So, what I’m really excited about is what happens next,” Bruchac told the group at day’s end. “Now these objects have been introduced to you, but it’s the technology to make them that needs young hands and young minds and young hearts to carry it forward and to help keep the stories alive.”

Frank Speck

Penn Anthropologist

FRANK GOULDSMITH SPECK JR. (1881–1950), was born in Brooklyn and raised in Hackensack, New Jersey. As a youth, he enjoyed sojourns into the forests and swamps of New Jersey and rural southern New England during family vacations. Speck entered Columbia University in 1899, and received his master’s degree in 1905 under the tutelage of John Dyneley Prince and Franz Boas, while conducting fieldwork among the Mohegan Indians in Connecticut. He came to the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) as a Harrison Fellow in 1907, and was the first student to graduate with a Penn Ph.D. in anthropology in 1908. From 1909 to 1913, he held a joint appointment as an instructor in anthropology and as an assistant in ethnology at the University Museum (now the Penn Museum). In 1913 he was appointed as an assistant professor and designated anthropology department chair, a position he held continuously until 1949. Speck was perhaps the most prolific ethnologist of his generation, with more than 300 publications, including books, scientific monographs, and articles. Over the course of five decades, he worked with Indigenous informants from Algonquin, Cherokee, Mohegan, Naskapi, Nanticoke, Penobscot, and other Native nations in the eastern United States and Canada.

—Excerpt from Margaret M. Bruchac, Savage Kin, page 141

FOR FUTHER READING

Armitage, P. “The Religious Significance of Animals in Innu Culture.” Native Issues 4 (1): 50–56 (1984).

Bruchac, M.M. Savage Kin: Indigenous Informants and American Anthropologists. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Bruchac, M.M., and B. Kelser. “Children Amongst the Caribou: Clothes for a Young Innu.” In Beyond the Gallery Walls. Penn Museum, Dec. 20, 2018. www.penn.museum/blog/museum/children-amongst-the-caribou-clothes-for-a-young-innu/

Burnham, D.K. To Please the Caribou: Painted Caribou-skin Coats Worn by the Naskapi, Montagnais, and Cree Hunters of the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992.

Speck, F.G. Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1935.

Williams, L.F., W. Wierzbowski, and R. Preucel, eds. Native American Voices on Identity, Art and Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005.