Contours of Inequality

Landscapes of Colonial Slavery on a Bahama Island

[authors]

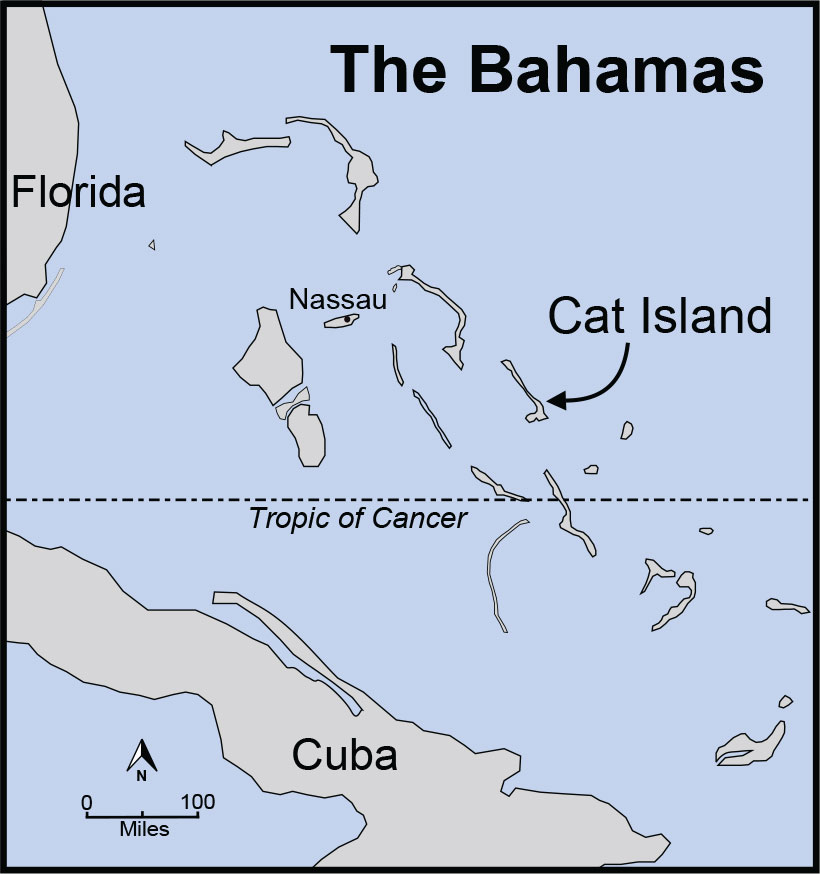

TOPOGRAPHIC RELIEF—the rise and fall of the land—may not immediately come to mind when pondering the history of West Indian slavery. But its importance has never been lost on descendants of those who worked the colonial plantations of Cat Island in the Bahamas. A case in point is the late Reverend Henry Pratt, a native of Bainstown on its southern shore. When asked a few years ago about pre-emancipation life there, the octogenarian responded pointedly, “The masters live on the hills, and all the slaves work in the bottom of the hill down the road. You see, the slave couldn’t live up on the hill.” His remarks, rooted in oral tradition, spoke to a significant relationship between the physical landscape and social order.

Like that of most of the estimated 1,300 native residents of Cat Island today, Reverend Pratt’s lineage harks back to a crucial episode in Bahamian history. His forebears, some six generations removed, were enslaved laborers brought to the island in the wake of the American Revolution. Their masters were mainland colonists who had pledged loyalty to King George III during the war. When Great Britain and the United States brokered peace in 1783, these “loyalists” sought refuge in other British domains. One destination was the Bahamas. With promises of land grants from the Crown, loyalists relocated and embarked on a plantation regime devoted to cotton. Within two decades, erosion and pestilence decimated their cotton crops, and their export economy foundered. Emancipation in 1834 sounded the death knell for the baronial lifestyle that many loyalist families had imagined.

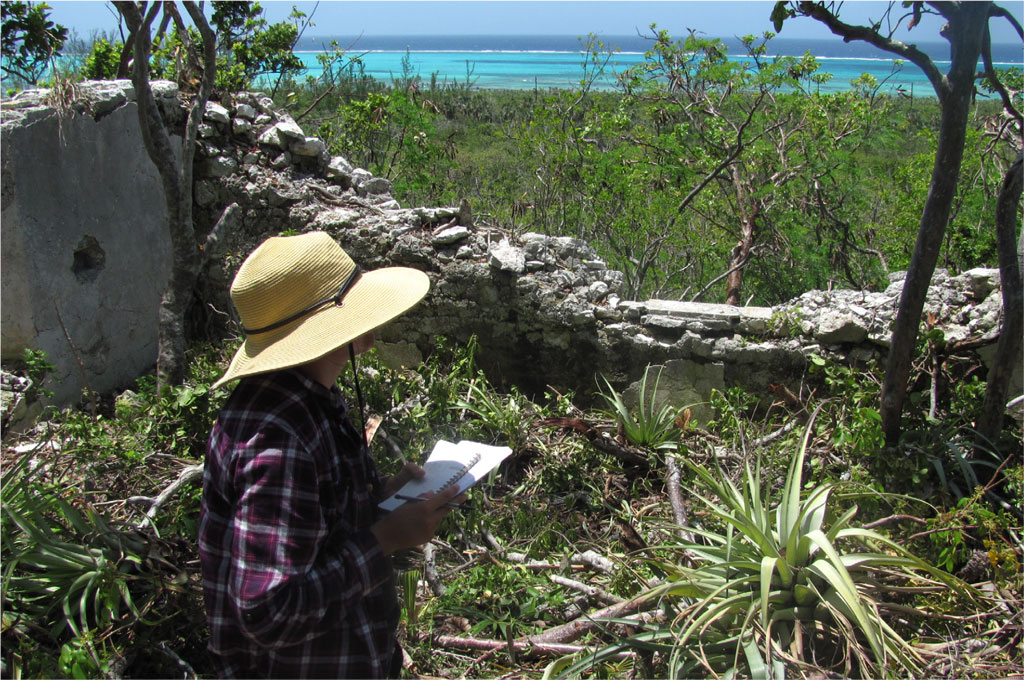

Around the time of Reverend Pratt’s interview in 2015, the first government-sponsored effort to record Cat Island’s old loyalist landscapes was just getting underway. The pastor’s reference to geography struck a chord with those of us who had taken up research there. We started investigating the principles that he had conveyed. Over the last seven years, we have explored the ruins of 15 loyalist estates, taking measurements and making systematic observations. What we have discovered in the forsaken dwellings brings Reverend Pratt’s understanding of the past into greater focus. The hills did indeed matter, though the inequalities of bondage were expressed on the landscape in more ways than his words might initially suggest.

Making Heritage Count

Despite its historical allure, Cat Island has received little attention from professional archaeology. No one knows how many loyalist sites there are, and the organizing principles of the deserted settlements languish in obscurity. To rectify this situation, the Bahamas Antiquities Corporation encouraged the conception of the Cat Island Heritage Project. The endeavor, sponsored by Eckerd College in Florida and Bahamian associates on the island, aims to make an inventory of sites relating to colonialism, slavery, and emancipation. The long-term goal is a heritage management plan that sets priorities for preservation, tourism, and public education.

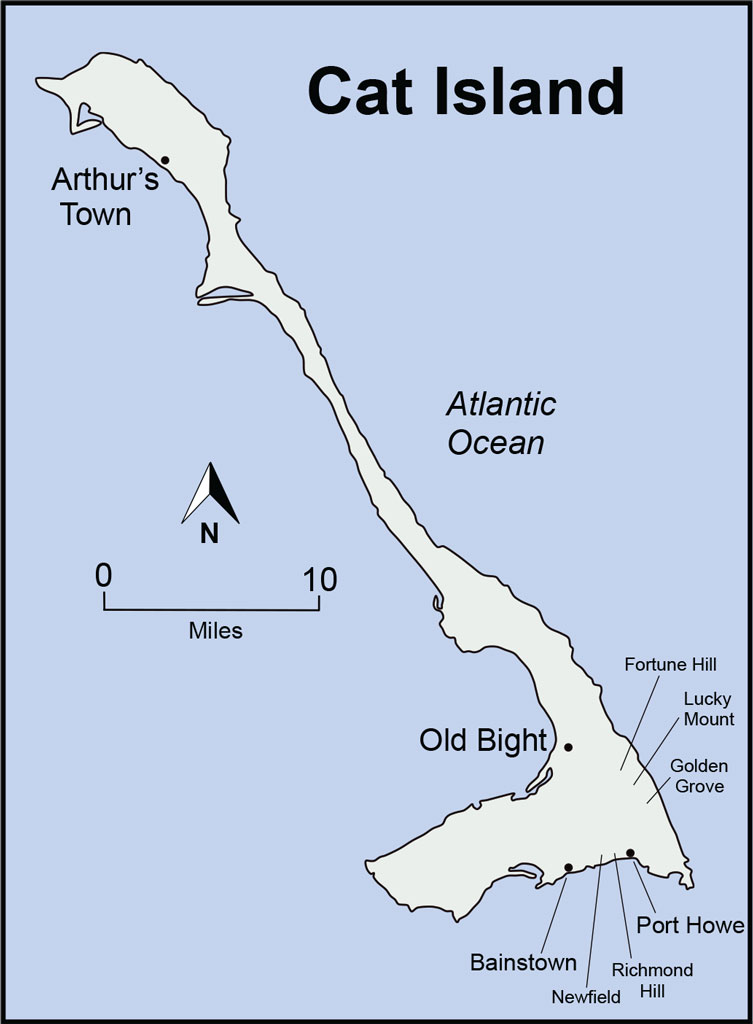

A special facet of the enterprise is collaboration with local communities. Partners with ancestral connections to these locations help to shape the research design. They set priorities for fieldwork by identifying specific sites and landscape features they want to investigate. They also urged us to engage the island’s youth. As a result, an annual program brings together 10th- and 11th-graders from Old Bight High School to work alongside Eckerd undergraduates. Students learn surveying skills and contribute to the data collection. They also cooperate on a service project, which involves recasting a cottage in the hamlet of Port Howe as a museum and cultural center.

Chasing Fences

The quest for plantation ruins incorporates archival documents, geospatial technologies, and ground surveys. While old maps and satellite imagery provide clues, we rely foremost on the experience of residents who know the island. Farmers cut plots out of the forest. Herders set goats to graze in some of the countryside’s most distant reaches. Islanders continue a proud tradition of bush medicine by venturing into the woods to collect plant materials for herbal remedies. Once off the beaten path, their mental pictures of the tangled landscape are often cued by stacked stone fences. These three-foot-high barriers, known locally as “slave walls,” crisscross the island in a latticework of right angles. Most date to the loyalist era when they marked the boundaries of fields, pastures, and quarters.

Almost every new field exploration starts with slave walls. Locals often guide us to a site by bushwhacking a trail that hugs a fence line. The walls traverse limestone terrain with jagged outcrops, thin soils, and scattered cobbles. Lurking among the rocks, especially in the rainy season, are land crabs that form an important part of regional cuisine. Every now and again, you pass a mocha-colored mound sprouting from a log on the forest floor. These termite skyscrapers can surpass six feet.

After a vigorous hike, usually uphill through a mix of gumbo-limbo, scrub palmetto, and pigeon plum trees, you find that the woodlands take on a different character. Bits of “queensware” and other 18th-century ceramics litter the surface. Someone may spot a venerable tamarind tree, a hallmark of past habitation. This tropical evergreen, with its massive trunk and drooping pods, can live over 200 years. The most timeworn specimens may well have been known to loyalists. Eventually, through filtered morning sunlight, someone notices a remnant of stone and mortar construction. Anchored in its stucco may be a Lignum vitae, a valuable hardwood and the Bahamian national tree. Having located the ruins, we clear undergrowth from key areas. Handheld GPS devices register altitude and place each building foundation into a predetermined grid of coordinates. Affixed to a tripod is a digital survey instrument with a laser that electronically measures distance. It allows us to record each structural footprint with fine-grained precision. The spatial data yield a two-dimensional site plan showing all visible surface features to scale.

Understanding the History of Cat Island

The Cat Island Heritage Project combines archaeological data with other sources of information. Vintage maps at the Department of Lands and Surveys in Nassau identify property boundaries and landowners after the loyalist exodus. Period newspapers on microfilm at the University of Florida Libraries contain descriptions of plantations for sale. Copies of British colonial wills, appraisals, and slave registers at the Bahamas National Archives offer insight into the communities that once occupied the old estates. Among recent archival revelations was an 1807 probate inventory for Nathaniel Munro, a loyalist who owned Richmond Hill Plantation. In addition to a wind-powered cotton gin and some livestock, the ledger lists the first names of 40 enslaved people. Most appear in one of eight family blocs, and each family has an associated monetary value in both dollars and pounds sterling.

The national archives also house birth and death records that lend clarity to the bonds that Cat Islanders have with key heritage sites. We learned, for example, that the Hunter family of Port Howe represents 4th-, 5th-, and 6th-generation descendants of Henry Hunter (ca. 1822–1891). Henry was a youngster at Golden Grove Plantation when Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act went into force in 1834. His lineage continued farming parts of Golden Grove after his death, and they do so to this day.

Conversations with the Hunters and other descendants certainly enrich our understanding of bygone years. They also entrust archaeology with an element of social responsibility. We have created a questionnaire to assess what locals—namely senior citizens—know about the old places. To ensure that the approach was ethically grounded, the Institutional Review Board at Eckerd College vetted our methods. As interviews take place, we deliver audio recordings and transcriptions to participants and consign the interviews to strategic partners working on the Port Howe museum. By sharing oral tradition and life experiences, community members contribute to the production of knowledge about Cat Island’s past. They address gaps in the documentary record, and they open our eyes to new ways of interpreting material remains.

Inequality in 3D

Of the sites that we have probed, a half-dozen stand out for their magnitude. This group, defined by more than ten buildings per locale, includes once-formidable estates with bullish names like Fortune Hill, Lucky Mount, and Golden Grove. Buildings in this subset lie at higher elevations, normally 80–140 feet above sea level. The ridges are nevertheless uneven, and our site plans reveal a link between each hill’s natural relief and social inequality. The largest dwelling in terms of interior square footage usually assumes the most favorable perch. We generally understand this building, with its ocean panoramas, to be the house of the proprietor or manager. As one descends the hill, even in slight intervals, each successive domicile tends to be smaller than the last. By no coincidence, this relationship also translates into measures of nearness. The farther a dwelling is from the pinnacle, the smaller one can expect it to be. In this light, the landscape pattern takes on a three-dimensional quality. The resulting hierarchy evokes not only the colonial universe of master and slave, but also the servile pecking order.

An exception is Newfield, the plantation of Henry Williams. Williams was an attorney and judge of Carolina stock, and his 600-acre estate once housed 75 enslaved souls. The residential ruins lie across two hilltops separated by a quarter mile. The eastern hill features an imposing eight-sided structure with raised foundation, high walls, and central chimney. We suppose this to be the Williams house. A smaller octagonal edifice may have accommodated his housekeeper, a free woman. Additional dwellings in the complex likely lodged domestic servants and enslaved workers of special authority. The western hill, by contrast, was apparently a settlement for low-ranking field hands. There is an orderly arrangement of one- and two-room masonry cottages, each with a fireplace and fenced backyard.

Eckerd students measured the ascent of intact masonry at each Newfield dwelling. We found that maximum architectural height also declines incrementally with distance from the owner’s house. Although it was not at the highest natural point on the estate, the Williams house appears to have been the highest visible point on it. Its chimney extends 20 feet above ground surface: a commanding elevation relative to other buildings. Such visibility projected authority, the way a soaring church steeple looms over a rural village. The next closest building—a duplex hosting the owner’s kitchen—has two chimneys that each rise 16 ½ feet. Being on a slight eminence, these shorter smokestacks just approach the apex of the Williams house. Beyond the duplex is another octagonal residence, but one with no chimney and walls reaching less than 11 feet. The smallest cottage on the owner’s hill has walls standing just 7 ½ feet high. And what of the modest cabins on the neighboring hill? None have chimney stacks, and together they average less than 7 feet in wall height.

Like Moonshine in the Nighttime

Allan Meyers, Ph.D., is Professor of Anthropology at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida. He is director of the Cat Island Heritage Project.

Megan Adams is an anthropology major and Ford Apprentice Scholar at Eckerd College. Her senior thesis examines the loyalist landscapes of Cat Island.

FOR FURTHER READING

Meyers, A. “Striking for Freedom: The 1831 Uprising at Golden Grove Plantation, Cat Island.” International Journal of Bahamian Studies 21(1): 74-90 (2015).

Meyers, A. “Enigma of the Shallow Seas.” Current World Archaeology 2017-86: 30–35 (2017)

Saunders, G., and M. Craton. Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People, 2 vols. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

Wilkie, L., and P. Farnsworth. Sampling Many Pots: An Archaeology of Memory and Tradition at a Bahamian Plantation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005.