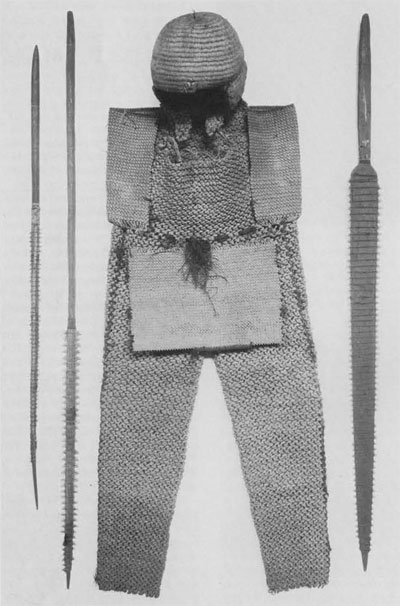

In November 1914 and January 1915 the Anderson Auction Company of New York offered for sale a collection of letters, manuscripts, books, portraits, and curios which had been the personal property of Robert Louis Stevenson (Fig. 1). The list of curios included more than two hundred objects collected by Stevenson during the six and one-half years he traveled and lived in the South Seas. The University Museum bought some twenty of them, with money contributed by John Wanamaker. Of the Museum’s purchases, perhaps the most spectacular were three coconut fiber corselets from the Gilbert Islands. As the Anderson catalogue observed, the three corselets “are all of extreme interest, being the Royal presents given by King Tembinoka, the Tyrant of the Island of Apemama . . . to R.L. Stevenson on the occasion of his departure from the island in 1889 (Anderson catalogue, Part I [1914] p. 87). The following is the story of these three corselets.

![South Sea curios from the colelction of Robert Louis Stevenson, on display at the Anderson Auction Galleries in New York. Besides the three Gilbert Island corselets (P3294 A,B,C), The University Museum purchased the Marshall Island navigational chart at rear left (P3297), the Hawaiian neck ornament draped over the coreslet at the left (P3288), and the Gilbert Island human hair necklace hung on the corselet at the right (P3287). Reproduced from the Anderson Catalouge, Part I [November 1914], by permission of the Princeton University Library.](http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/files/1986/11/south-sea-curios-robert-louis-stevenson.jpg)

Reproduced from the Anderson Catalouge, Part I [November 1914], by permission of the Princeton University Library.

Fiber Armor

European visitors to the Gilberts during the 19th century described the inhabitants of these atolls as the most warlike people in Micronesia, if not in the world. Fighting was, they reported, a constant preoccupation, and almost everywhere they went they saw islanders with numerous scars on their arms and legs (Wilkes 1849: 47, 93). The weapons that inflicted most of these wounds were spears, swords, and small hand weapons made of coconut wood and lined with rows of sharks’ teeth, the common use of sharks’ teeth on weapons being especially characteristic of the Gilberts. Even more ingenious, and unique to the Gilberts and neighboring Nauru and Ocean Island, was the protective clothing devised as a defense against these weapons. This included overalls, jackets, and corselets made of coconut fiber (Figs. 3, 4), helmets of coconut fiber or the dried, inflated skin of the porcupine fish (Diodon), and wide belts of coconut fiber or ray skin.

The islanders seemed to believe that in their armor they were invulnerable.

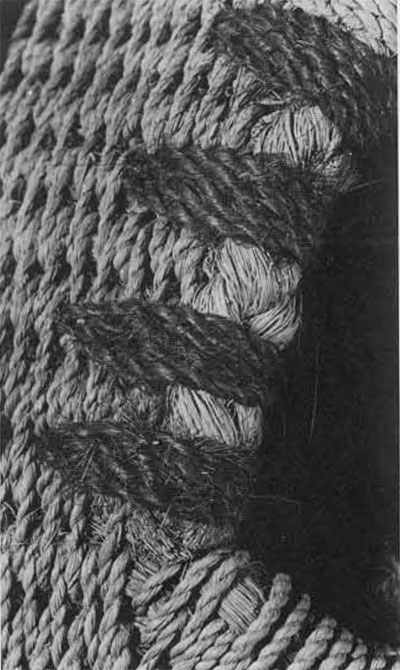

Coarse fibers from the husks of mature coconuts provided the raw material for construction of the armor. These were combed and hand- “spun” by rolling on the thigh, producing smooth fiber with a long staple which could then be twisted into cord. The overalls and jackets were made of cord netting, coarse and flexible but very strong. The corselets, fiber helmets, and some of the fiber belts were made of long bundles of fiber (three-ply braids, actually), bound together by twisted fiber cord (Fig. 5). For a helmet, these bundles were bound in a spiral, and in the corselets and belts they were laid horizontal and parallel. This method of construction produced an armor of great weight and rigidity.

![Warriors of Tabiteuea, in the Gilbert Islands, with weapons edged with rows of shark's teeth and protective armor made of coconut fiber. The netted jackets and overalls were actually loose and baggy, and the ovceralls continued over the tops of the feet. (Engraving based on a drawing by A.T. Agate for the United States Exploring Expedition Vol. 5 [1894], p.48)](http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/files/1986/11/warriors-of-tabiteuea-gilbert-islands.jpg)

European firearms and knives were available from the early days of contact, and became important items of trade. Guns were not always used to advantage, but knives were more widespread and effective, and bayonets attached to long poles were especially popular, corresponding as they did to the long island spears. The islanders continued to use their indigenous weapons, and the fiber armor still provided protection against them, as well as against knives and bayonets.

John Kirby, a beachcomber who lived on Kuria from 1838 to 1841, reported to the United States Exploring Expedition that “this armour has been only a short time introduced or in use on the islands, and is not yet common in all of them” (Wilkes 1849:93), but this observation is uncorroborated and in fact no one really knows when the armor was invented. It may have been used nearly as long as there was fighting, which was up to the establishment of the British Protectorate in 1892. Otto Finsch reported that on Tabiteuea in 1879, after a bloody battle between the converted and unconverted, 300 spears, 79 muskets, and “many” corselets were handed over to the mission to be burned (1893:36). At the time of his visit in 1880, the islands were in a state of war, and he saw armed bands here and there, some in “very droll attire.” About the same time, Richard Parkinson observed armor worn in battles between the people of Abaiang and Tarawa, and on the island of Nonouti (1889:45-47).

The Dynasty of Abemama

During seventy years of intensive European contact, from the 1820s through the 1880s, Baiteke who faced the full impact of the European presence, and in 1851 he made his first move. By “a deliberate act of policy” he had all resident foreigners, nine on Abemama and twenty-five on Kuria and Aranuka, killed. In the following decades he controlled all trading transactions, including the import and distribution of firearms, prohibited the importation of alcohol and the manufacture of sour toddy from coconut sap, forbade any permanent missionary presence on Abemama, and absolutely banned labor recruiters from all three islands (Maude 1970:206212).

In 1878 Tem Baiteke retired in favor of his eldest son, Tem Binoka. Tem Binoka was “self-centered and arrogant, … but … he possessed all his father’s intelligence, and an intellectual curiosity, particularly concerning the ways of the outside world, which never left him” (Maude 1970:212). In 1873 he persuaded his father to allow a mission teacher to visit Abemama, and from this person he learned written Gilbertese, some arithmetic, and some geography. He strictly enforced his father’s policies in regard to alcohol, firearms, and labor recruiters, and reserved the copra trade ‘as a royal monopoly. He put down at least three major revolts, the most serious of which occurred as late as 1885. Tem Binoka’s uncle, Tem Binatake, was involved in the first and third of these revolts, and after the first his nephew banished him from Abe-mama. In the 1880s Tem Binoka attempted, unsuccessfully, to conquer the entire Gilberts group (Maude 1970:212-222).

All things considered, the accomplishments of Tem Baiteke and Tem Binoka were extraordinary. Together they achieved a feat unique in the history of the Pacific Islands: in the face of European cultural pressures that had overrun the whole of Polynesia and Micronesia they had maintained the political, economic, and social integrity of their territory from the beginnings of European contact to virtually the end of the nineteenth century, selecting and accepting from the European only such ideas and material goods as appeared to them of value, and these strictly on their own terms and not those dictated by the dominant race. (Maude 1970:223-224)

Stevenson and Tem Binoka

Robert Louis Stevenson first visited the Gilbert Islands in 1889, on the second of his three South Sea cruises. On 24 June 1889, Stevenson, his wife Fanny, her son Lloyd Osbourne, and the Stevensons’ Chinese cook left Hawaii on the Equator, a small trading schooner headed for the Gilberts. After stopping for six weeks on Butaritari (Fig. 7), the party reached Abemama on 1 September.

The main objective of the Steven-sons’ voyage to the Gilberts was to visit the notorious Tem Binoka. Tem Binoka was by that time in his mid-forties and near the end of his life, but his fame was undiminished. “There is one great personage in the Gilberts: Tembinok’ of Apemama: solely conspicuous, the hero of song, the butt of gossip. Through the rest of the group the kings are slain or fallen in tutelage: Tembinok alone remains, the last tyrant, the last erect vestige of a dead society” (Stevenson 1891:299).

When the Equator anchored in the lagoon, Tem Binoka’s own ladder was brought out and lashed to the side of the schooner and, after some delay, Tem Binoka himself came out, mounted the ladder, and descended heavily to the deck. He was a dramatic figure:

…a beaked profile like Dante’s in the mask, a mane of long black hair, the eye brilliant, imperious, and inquiring…. Now he wears a woman’s frock, now a naval uniform; now (and more usually) figures in a masquerade costume of his own design: trousers and a singular jacket with shirt tails, the cut and fit wonderful for island workmanship, the material always handsome, sometimes green velvet, sometimes cardinal red silk. This masquerade becomes him admirably. In the woman’s frock he looks ominous and weird beyond belief. (Stevenson 1891:303)

The arrival of Tem Binoka occasioned considerable anxiety on the part of the Stevensons, for they had a favor to seek. “It was our wish to land and live in Apemama, and see more near at hand the odd character of the man and the odd (or rather ancient) condition of his island” (Stevenson 1891:309). The captain of the Equator presented their request, but Tem Binoka did not respond. To their discomfort, for the rest of that day and half of the next, when he returned to the ship, he subjected the party, one by one, to an intense, silent scrutiny. At the end of that time, wrote Stevenson, “I was informed abruptly that I had stood the ordeal. ‘I look your eye. You good man. You no lie,’ said the king: a doubtful compliment to a writer of romance” (1891:312).

The party was allowed to come ashore, and Tem Binoka had assembled for them a little town, the four houses, which stood on stilts, being simply walked into place on the shoulders of islanders. The Stevensons lived in “Equator Town” for two months. They got to know the “commons” of the island hardly at all, but Tem Binoka very well. They called on him in his house, and he came to call on them.

He would come strolling over, always alone, a little before a meal-time, take a chair, and talk and eat with us like an old family friend. . .[His manners were] plain, decent, sensible, and dignified. He never stayed long nor drank much, and copied our behaviour where he perceived it to differ from his own. . . . It was plain he was determined in all things to wring profit from our visit, and chiefly upon etiquette. (Stevenson 1891:334-335)

As time went on, Tem Binoka told Stevenson the story of his family. He described his grandfather, Tenkoruti (Teng Karotu), a village chief “when Kuria and Aranuka were yet independent [and] Apemama itself the arena of devastating feuds”:

Through this perturbed period of history the figure of Tenkoruti stalks memorable. In war he was swift and bloody. . . . In civil life his arrogance was unheard of…. He was feared and hated, and this was his pleasure. He was no poet; he cared not for arts and knowledge. “My gran’patha one thing savvy, savvy pight,” observed the king. (Stevenson 1891:364)

His grandson remembered Teng Karotu as an old man: he was tall and lean and “walked all the same young man.” According to Tem Binoka, the body of Teng Karotu was unscarred (Stevenson 1891:365).

Tem Binoka described his father, Tem Baiteke, as “short, middling stout, a poet, a good genealogist, and something of a fighter” (Stevenson 1891:365).

It was his father’s brother, Tem Binatake, however, who increasingly emerged in Tem Binoka’s recollections as the truly great man:

Like Tenkoruti, he was tall and lean and a swift walker . . . . He possessed every accomplishment. He knew sorcery, he was the best genealogist of his day, he was a poet, he could dance and make canoes and armour . … But these were avocations, and the man’s trade was war. “When my uncle go make wa’, he laugh,” said Tembinok’. . . . (Stevenson 1891: 365)

As the time of the Stevensons’ departure approached, Tem Binoka became increasingly melancholy. One night he sat with Lloyd Os-bourne after the others had retired:

“I very sorry you go . . . . Miss Stlevens he good man, woman he good man, boy he good man; all good man . . . . I very sorry. My paths he go, Miss Stlevens he go: all go. You no see king cry before. King all the same man: feel bad, he cry. I very sorry.” (Stevenson 1891:367-368)

![When Augustin Kramer went to the Gilberts in 1898 to collect ethnographic specimens for the Stuttgart Museum, he acquired many weapons and pieces of armor on the island of Tabiteuea. Wanting to find out how people fought, he introduced the men who brought them to throw on the armor and pose with the long spears. Reproduced from Augustin Kramer, Hawaii, Ostmikronesien und Samoa [1906]](http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/files/1986/11/gilbert-island-inhabitants.jpg)

Reproduced from Augustin Kramer, Hawaii, Ostmikronesien und Samoa [1906]

Like his father and uncle before him, Tem Binoka was a poet, and on the occasion of Stevenson’s departure from Abemama the two men agreed to “celebrate [their] separation in verse”:

Let us, who part like brothers, part like bards; / And you in your tongue and measure, I in mine, / Our now division duly solemnise. (Stevenson 1911:180)

Stevenson’s poem “The House of Tembinoka,” written at sea on the schooner Equator, repeats in verse the history of Tem Binoka’s family.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s three Gilbertese corselets lie, dusty and mute, in the storerooms of The University Museum. As it happens, we know quite a lot about them. We understand something about the friendship between Stevenson and Tem Binoka, and how the gift was made. We can picture the jagged wounds inflicted by rows of sharks’ teeth, the long complexity of binding scores of bundles of fiber into a substantial defensive garment, and the incredible discomfort of wearing a full suit of fiber armor into battle in the blinding heat of an equatorial atoll. The names of the three men who made and wore these corselets are known to us, and we can even ask ourselves, which belonged to whom? Is P3294C, with its fine texture and many small torn spots, older than the other two, and was it, therefore, worn by the arrogant old warrior Teng Karotu? No matter how far we push, however, some frustration remains, and perhaps this is part of what draws us to an ethnographic and archaeological museum. Firmly in the here and now, we can never really know what it was to make and use the exotic objects that surround us, but we come, nevertheless, to look and learn and speculate.