Ethnographic interest in Iran has a long history. It goes back to the first European travelers in the Middle Ages who took an intelligent interest in what they saw, as they moved through ( what were to them ) the culturally strange lands of the East to visit the courts of the potentates of the time. We have progressed a long way since then in the mutual understanding and interpretation of widely differing cultures, and the Middle East and Iran have also changed. But, for a variety of reasons (which are too complex to rehearse here ), professional anthropology has been slow to start in the Iranian cultural area, and the expertise of professional ethnographic description and anthropological analysis has scarcely begun to be applied to Iranian culture and society. To some extent this has been true of the Middle East in general, but anthropological interest in Iran is even more recent than interest in the Middle East as a whole. Until very recently, except in the special field of Iranian languages, Iran’ was treated academically as an appendage of the Arab Islamic world. (It is significant that many people outside academe do not realize that the Iranians are Indo-European. They know they are Muslims, and think of the whole Middle East as Semitic. In fact, of course, Iran has a separate cultural tradition, older than that of the Arabs, which though secondary to it in Islam, is an integral component of Islamic culture.) The early references to Iran in works of anthropological orientation on the Middle East are by people who had not specialized in Iranian ethnography (e.g. Elisabeth E. Bacon, Carleton S. Coon, Raphael Patai).

The first significant anthropological monograph concerned with Iran, Nomads of South Persia by Fredrik Barth, appeared in 1961. Barth, who is Norwegian and was trained partly in Great Britain and the United States, was concerned with a group of pastoral nomads—the Basseri—and treated primarily the structure of power and authority within the tribe, against the background of their relationship with the natural environment. It was hailed as an exemplary analytical work and soon found a place in the core of anthropological literature. It is now one of the best and best known anthropological monographs on the Middle East. It is still unique in the anthropology of Iran. Barth has also written several articles and papers which draw on his Iranian data and have contributed a firm basis to our studies of pastoral nomadism and tribal organization in the Iranian area.

Barth’s work encouraged a number of students in North America and elsewhere to build on that basis. Studies have now been made among Bakhtiari, Baluch, Kurds, Mamassani, Shahsavan, and Turkmen groups. A number of doctoral dissertations have already been completed, and some interesting monographs may be expected in the next few years. However, the whole of this effort has been directed towards pastoral nomadism. Because of the nature of the relationship between nomadism and settled life in Iranian history, this leaves the anthropologist with an unbalanced view of Iranian culture, though it has proved a valuable contribution to general anthropological knowledge.

Anthropology grew into a fully fledged academic discipline by feeding on data from a selection of cultures around the world, which had in common the condition of being controlled at the time by one or another colonial power. A corollary of this condition was their lack of a written tradition and consequent historical consciousness.

When anthropologists turned to the study of societies like those of the Middle East, which did not fall into this category, but had enjoyed a literary Great Tradition which in some cases reached back to the beginnings of history, it took them time to realize—it is perhaps not even yet fully realized—the need to modify their research methods and their formulation of research problems, as they had already been required to do in Mesoamerican and Mediterranean studies. This explains why the first interest of anthropology in Iran was nomads—the groups furthest away from the Great Tradition—and why a large proportion of current research is concerned with villages and cities.

It needs to be mentioned here that the Iranians themselves were not affected by this particular academic legacy in their own studies of their folk culture, and their own approach has for that reason been quite the opposite. Private scholars and, more recently, teams from the Institute of Social Studies and Research of Tehran University and the Folklore Department of the Ministry of Fine Arts concentrated first on settled communities, and have only very recently turned to the sudy of nomadic groups. These studies together with related work in historical geography and local histories have accumulated a vast store of ethnographic data—which are unfortunately inaccessible to most western scholars because of the language problem. Very few western scholars achieve the level of proficiency in conversational and literary Persian which would allow them to treat usefully both the Great and the Little Traditions in Iranian culture and communicate efficiently with their Iranian colleagues. None of the Iranian work is available in English and very little western anthropology has been translated into Persian.

There have been studies of settled life in both villages and cities by western scholars, but these—insofar as they are yet published—have, significantly, been made not by anthropologists, but by scholars in the allied social sciences. One in particular, City and Village in Iran by Paul Ward English, deserves mention here because of its role, as early as 1966, of bringing to the attention of anthropologists working in the Iranian area, along with an excellent set of data, the problems of the intricate relationships between the various modes of Iranian society in a given region: e.g. city, village, and tribe, or market, agriculture. and pastoralism, etc.

There appears to be a general theme running through anthropological studies of communities and groups from Iranian society, from what might be called the real beginning in 1961, through to the present day when many studies have been completed and await publication, and many more are being conducted in the field—a theme, which becomes gradually more conscious and explicit, of the integration of Iranian society. Barth’s work stressed, among other things, important economic interactions between nomad and peasant in south Iran, and sketched a number of diachronic models of demographic interaction showing the economic and other related factors which cause individual nomads to “drop out” into the peasant’s world and vice versa. This was the first explicit suggestion that “nomad” and “peasant” were not fixed unchangeable identities, but that nomads could and did under certain conditions become peasants, and peasants nomads, despite the avowed dislike of each for the other and his way of life.

English’s work stressed the integration of city and village and sought to show the dependence of the villages of the Kerman basin on the city of Kerman for the investment and financing without which they could not continue to exploit their meager resources.

The studies now being prepared for publication each bring out aspects of integration: e.g. the political relationship between the central government and the tribal organization and ecological adaptation of a group of pastoral nomads, the cultural dependence of nomads on the Great Tradition, and the formation of certain leadership roles in the articulation of nomadic groups with the society at large.

The isolation of outlying communities and nomadic groups appears to have been characteristic of a transitional stage between mediaeval and modern society, brought about most obviously by the abrupt change in communications from wheel-less traffic to powered vehicles. Before the motor age there were arterial caravan routes which channelled the more important long distance traffic. But, comparatively, there were far fewer obstacles to foot travel before than there are to motorized communication now. With the introduction of motorized traffic, routing became much more selective, and large areas of the country were immediately isolated from the major routes of communication. This situation is only now being corrected—with the recent increase in road building and planning. Many villages, which we are accustomed to thinking of as severely isolated, were much less so thirty years ago (relative to the total communications situation at the time) and are now once again being brought back out of their state of isolation. When anthropologists started to work in Iran isolation was a more important factor than it is now.

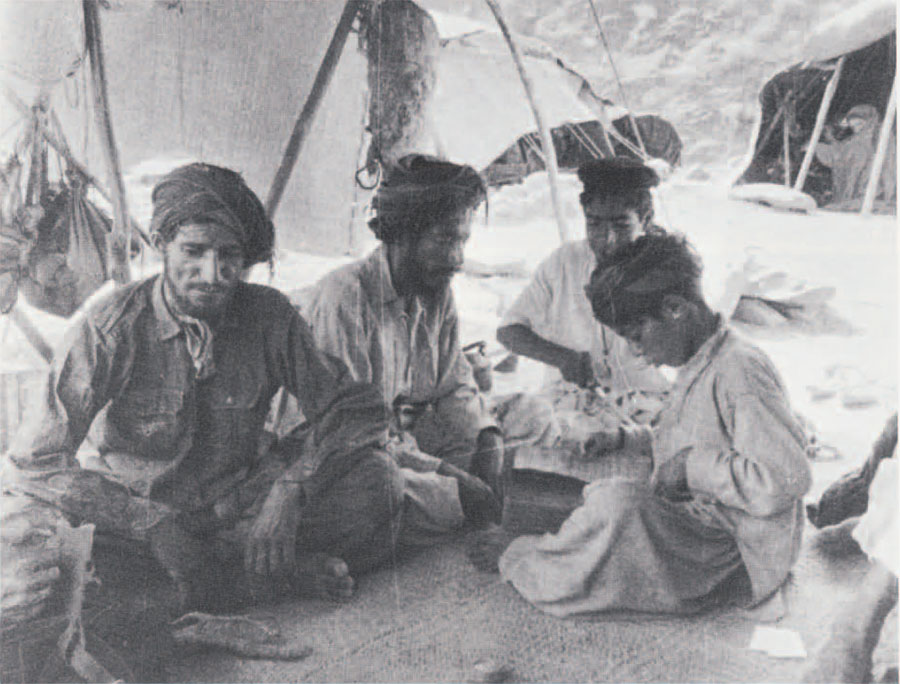

The development of my own research interests in Iran over the last thirteen years serves as an example of these general trends. I sought isolated groups, and still seek them, but for different reasons. To begin with I sought isolation from the effects of modern mechanization and the spread of industrially produced consumer goods. Now I know that this is no longer either realistic or possible and I choose subjects in the relative isolation of the eastern deserts in order to study traditional modes of interaction between peasant, nomad, and city, which would throw light on similar interaction in less isolated conditions. I first chose nomads—the Baluch—and in studying them gradually found that, among the Baluch, nomadic groups constituted only a part-society and could only meaningfully be studied as part of a larger social universe. Among the Baluch, pastoral nomads and settled agricultural people carry one identity. In other areas of nomadic activity the settled and the nomadic identify themselves differently, but are still part-societies. Recently I have begun studies of isolated villages in oasis situations in the southwest corner of the province of Khorasan: Nayband and Deh Salm. In each case I had sought out particularly isolated villages in an attempt to find the answers to specific questions concerning the traditional relationship between old, isolated oasis settlements and the society at large against the background of the relationship between the community and its harsh desert habitat.

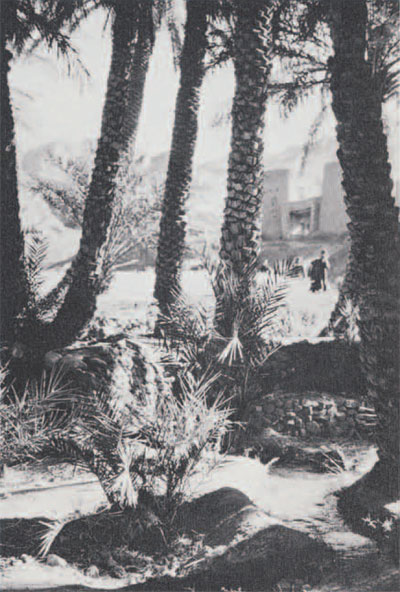

Nayband is an old watering place situated at a minor crossroads roughly in the center of the deserts of the Iranian plateau. It appeared from scanty references in the literature that the small population of around eighty families had remained fairly constant for over a millennium, relying on extensive date palm groves, a little agriculture, and the caravan traffic, but continually menaced by marauding bands of Baluch. A brief preliminary period of investigation showed that the primary subsistence base of the community was animal husbandry. The nature of the terrain and the water supply dictated that they should be settled and augment the feed of their flocks by cultivation rather than migration. Most of the fruit produced by the date palms was of very poor quality for human consumption. Some was converted into syrup, while the remainder was used as fodder.

Dates are a peculiar resource in that, when properly tended in ideal conditions, they produce large amounts of fruit—up to four hundred pounds of dates per tree per annum—and the productive Iife of a tree, barring catastrophes, is upwards of seventy-five years. A date palm grove, therefore, constitutes a considerable investment, and requires —compared to the more common subsistence crops such as wheat and rice—a minimum expenditure of time and labor. Nevertheless, that investment will not be made unless there is reasonable certainty that the investors will reap the profit rather than lose it to raiders. Assuming conditions where the investment can be made, a community relying primarily on a subsistence base of date palm cultivation is likely a priori to be structurally different from communities with other types of subsistence base, whether agricultural or pastoral. Nayband had turned out to be date-palm cultivating and agricultural and settled, but primarily pastoral in subsistence emphasis. The total situation, in its historical perspective, could not be properly understood outside the context of relations with marauders, the caravan traffic, and the nearest political center which was located in Tabas some one hundred kilometers to the north.

From the literature Deh Salm appeared to be a similar case. It is very isolated geographically and grows a similar range of crops, but it differs in that the route that traditionally passes by it has, at least in recent historical times, been minor compared to those that passed by Nayband. The population is also smaller (about forty families), but it has a larger cultivated area and a larger plantation of date palms. Like Nayband it has traditionally suffered from the insecurity inherent in such a geographical location. But this insecurity had affected it in a very different way. Deh Salm had become a political and an economic colony of political centers to the east and northeast of it (Neh and Birjand). The people had gradually been obliged to sell out their resources—land, water, and date palms—to outside investors. They continued to subsist from them, but in the capacity of tenants.

Only historical factors can explain why Deh Salm found outside investors and Nayband did not, and the study of both communities requires an appreciation of their total context of external relationships.

Anthropology generally has been tending towards more holistic interpretations and analyses, and the results of this tendency in the study of Iranian society may prove especially rewarding in view of the length of Iran’s historical tradition and the variegated wealth of its cultural content.