Since 1968 a team from the Town Planning Institute of Dalmatia and the University of Minnesota has been excavating in Split, on the Adriatic coast of Yugoslavia. The excavation is part of a program of joint Yugoslav-American archaeological research supported by the Smithsonian Institution through foreign currency grants. Two things are outstanding about the site: its origins, and its continuous history. Here stands one of the most important and best preserved monuments from the Roman world, the palace of the Emperor Diocletian. This palace has been continuously occupied ever since it was built, and is today the core of a thriving modern city. Archaeological investigation is simply another stage in its development. The attempts to discover the original character of the palace, and to trace the major changes in its use, are taking place in the middle of its continuing life, and are contributing to plans for its future.

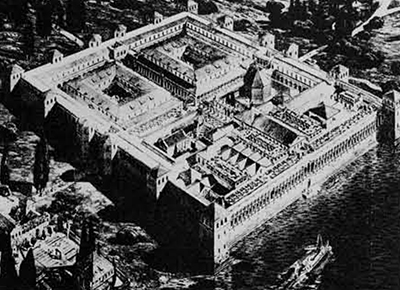

The degree of continuity is due to the adaptability of the original structure. Not so much a building as a large complex, it combines element: of the luxurious country estate, or villa, with those of the military fort, and incorporates features, such as a royal tomb, not usually found in either fort or villa. It is this combination of elements which makes the study of the original so fascinating, and which opened the way to its later life. Diocletian built the palace at the end of the third and beginning of the fourth centuries after Christ as a place of retirement following his abdication after a strenuous reign of twenty years. Two of his most famous policies, the attempts to annihilate Christianity and to control prices throughout the Empire, had failed, but he had nonetheles succeeded in establishing a measure of security after the troubled years of the mid third century. Now, it was said, he wanted to live in the country and grow cabbages. The elaborate structure he built for that purpose remains one of the most conspicuous testimonies, and permanent contributions, of his remarkable career,

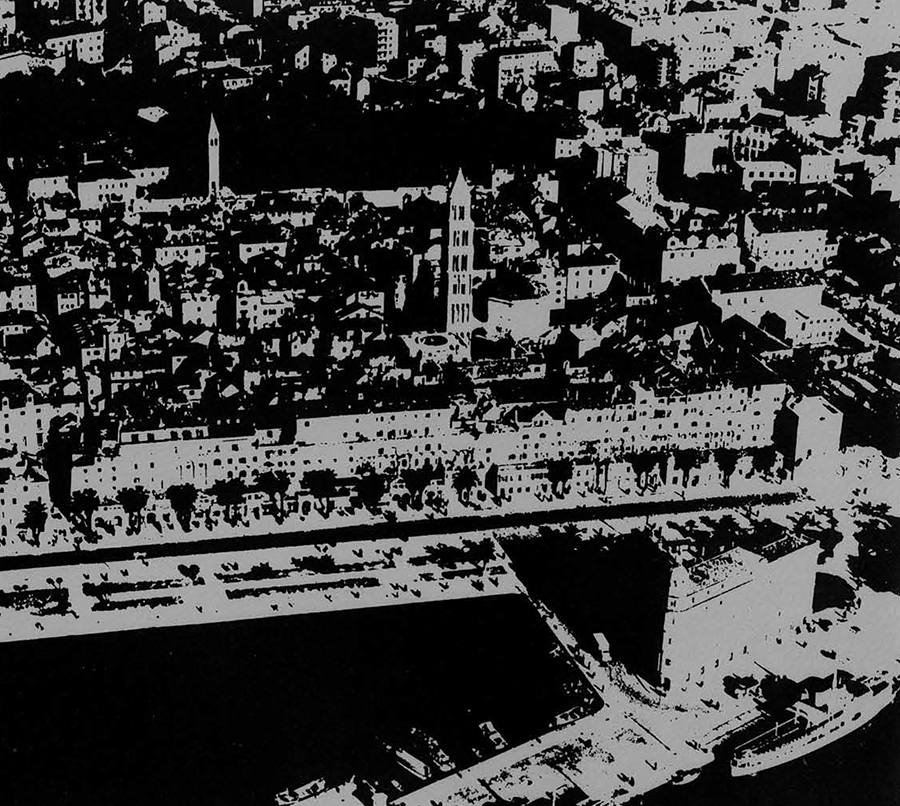

Split must have been a pleasant setting for his last years. The Dalmatian coast of Yugoslavia is a narrow strip framed between sea and islands on one side, mountains on the other. Halfway down the coast are the ruins of the ancient city of Salona, which in the Roman period was the capital of the province of Dalmatia. Tradition say that Diocletian was born there. By Salona, a small peninsula runs westward into the Adriatic, and there, on a broad, shallow bay facing south, the Emperor built his palace. Apparently the site was open country, with at most a small fishing village in the neighborhood.

Several centuries after Diocletian’s death, probably just after 614, recurrent barbarian invasions drove the citizens of Salona to abandon their good harbor, and seek shelter within the walls of the palace. These original walls encompass an area of about nine and a half acres right on the bay. The settlement which the refugees created has spread far beyond those limits. The city now reaches across the peninsula almost to the ruins of Salona and has a population of 140,000. This richness of past and present, with all the complexities in between, creates unusual problems, and offers unusual rewards to the excavator. Many of these have become clear only as work progresses.

When, in 1966, the University of Minnesota sent me to Yugoslavia to consider sites for possible excavation, I was attracted to Split partly by its continuity into the Middle Ages, but predominantly by its importance in the Roman period. Moreover, study of monuments has proved especially important in these centuries for correcting simplifications based on written sources. Diocletian’s palace appears in every beginning textbook of art history, but the plans shown are hopeful guesses, the gaps in our actual knowledge are great.

This is the period characterized by Gibbon as one of Decline and Fall. Art historians and archaeologists, however, have done a lot to modify that characterization, to show that while there certainly was great change, it was often accompanied both by material prosperity and by artistic creativity. Rightly or wrongly, scholars have also seen this as a period of rising influence from the East, and have tried to disentangle eastern and western influences in Diocletian’s palace. More exact knowledge about the original plan, the history of its construction, its original appearance and functions, could be expected to shed light on significant issues.

At the same time, I was interested in what we might be able to trace archaeologically of the process by which a palace becomes a city, and a Roman settlement becomes a Slavic one. I had no idea, however, of the rich medieval materials we were going to uncover, or of the complexities of interpreting them. It has become increasingly clear that study of the pottery alone will form an important contribution to medieval archaeology. A third aspect has also become absorbing for all of us who have worked in Split, and that is planning for the future. American participation in the joint program has been limited to excavation and preliminary conservation. Our Yugoslav partners also endeavor to prepare the ancient spaces for new uses.

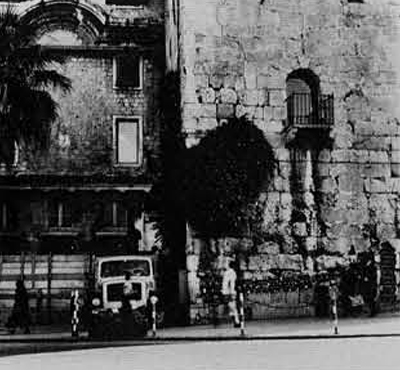

The Town Planning institute of Dalmatia is largely responsible for inaugurating the new era of work in the palace. Study of its remains had begun in the eighteenth century with the five-week visit of the Scottish architect Robert Adam. At the beginning of the twentieth century two major books appeared, those of George Niemann and of Ernest Hebrard working with Jacques Zeiller. Their works indicate clearly the gaps in their information, but propose restorations which have usually been accepted uncritically. Until quite recently, little archaeological investigation was done. Hebrard made a few soundings, and so did the prominent Yugoslav scholar, Franc Bulic.

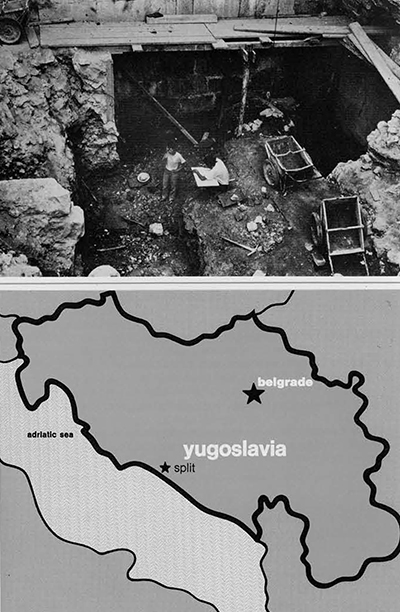

Extensive excavation first began in 1968 in the atmosphere of social, cultural, and economic expansion which has characterized Yugoslavia since the end of the Second World War. Work at Split was initiated by the Institute for the Preservation of Monuments of Dalmatia, and continued by the Town Planning Institute under the direction of Jerko Marasovic, now Yugoslav co-director of our work. Large areas of the southern palace substructure were cleared. Discoveries included baths in the southwest, and two round temples. Working conditions were difficult. No stratification was preserved in the areas dug, and there were few finds of pottery or other small objects.

Two basic principles govern recent archaeological work in Split. Both arise from a conception of the palace as a continuing entity. The first is that the accretions of successive periods should be preserved, and added to. No one wants to clear the whole area to its Roman levels. Valuable structures of later periods will remain, and new ones will be built. One view may some day take in a pre-Romanesque belfry on a Roman wall flanked by a Renaissance palazzo. It will also take in the clotheslines and television aerials of the inhabitants, because the second principle is that conservation of older structures is best achieved by assuring their continued use. Split has survived as it has because many of its parts were viable through the centuries. The Mausoleum became, and continues to be, a church: it is proposed that Diocletian’s dining room become a restaurant. After archaeological investigation is completed the palace should emerge, not as a museum, but as a revitalized urban core.

A study made in 1966 showed that many buildings within the Roman walls were substandard, and that much space was being used for storage, rather than for residential or commercial purposes. The city hopes to change this. Excavation is carried on in areas which will be renovated. We have excavated in a garden, in a hotel basement, under the floors of shops, and in spaces cleared by demolition of substandard housing. The planners wait to see what will be discovered about the history of an area, so that future building can always preserve and respect earlier remains, perhaps incorporating them for some new use.

Each situation calls for a different solution. We worked in one area which had been a small square by an old house. The house was demolished. The excavation uncovered buildings from a variety of periods. First, in Diocletian’s time, a bath had been built there—the second one discovered in the palace, called the eastern bath. By it were more Roman walls, perhaps a little later. Then, after debris had accumulated for a while, some crude medieval walls had been added in an open space outside the bath. Finally, the bath was partly demolished, and the whole space was occupied by solidly built medieval houses and a narrow street. From this sequence many inferences can be drawn about a changing society, its technology, population, standards of living, etc. We took down some of the later walls to study the bath heating system, but did not want to clear the whole site to its earliest level. Instead, enough was left to illustrate the historical sequence. There is no way that a site containing such segments from different periods can be reconstructed and reused. In this case, therefore, concrete slabs cantilevered from six columns will span the whole space. It will resume its original function in the town, but anyone who is interested will be able to descend beneath the paving to see a bit of the early history.

On the other hand, the ground floor room which we cleared in the southeastern tower is completely preserved, and all Roman: its walls are of solid ashlar construction with the original door and windows. Its original ceiling, which was of timber, had long gone, and a new ceiling had recently been built, which allows the holes and corbels for the original beams to show. The floor is of many laminated layers of mortar, and has become uneven with the passage of time. A new floor will have to be placed above it, and then the space can serve as a shop or office. There is even a tentative proposal to put down a transparent floor over the beautifully preserved hypocausts of the western baths and have a discotheque there.

Only this belief that study of the past is an integral part of the development for the future makes our work possible. Excavation in a city requires the closest cooperation with a variety of local authorities. When Robert Adam landed in Split, he found that “to the soothing expectations of the pleasure of my task, the certain knowledge of its difficulties soon succeeded.” Everyone who has tried to work here has encountered the same problems he enumerates, arising from the building of modern houses into older structures, but the suspicions of the Venetian governor made Adam’s position untenable. In our experience the grave technical difficulties have been greatly alleviated, although never totally solved, by the sympathy and enthusiasm of both officials and private citizens. The Housing Enterprise has concentrated its urban renewal efforts in the quarter where we wished to work. The Water Board has rerouted water and sewage lines around our trenches, once in advance, several times unexpectedly, since the position of pipes laid in the Austro-Hungarian period is not always known until we discover them. A cobbler vacated his shop for a month last summer, leaving shoes hanging on the walls while we dug beneath his floor to trace a mosaic. Last winter for several days people jumped sidewise out of their house door so that we could look for continuation of the eastern bath walls under the city street.

The most persistent problems have been statics, earth removal, and water seepage. The static problems are caused by past building activities. It appears that sometime in the late Middle Ages or early Renaissance (fourteenth to fifteenth centuries) there was, at least in the southeastern palace area, a period of rebuilding which dwarfs any renovation before or since. Great pits were dug to remove stone from the Roman walls for reuse. The debris from demolished buildings collapsed or was dumped into these pits, and on any free spaces. Houses were then built precariously over the half-destroyed walls and the loose fill. In the first year of our excavations John Wilkes from the University of Birmingham in England began to map some of the rooms in the southern palace block, right beside the east wall. In one sounding, he reached the Roman floor almost ten meters below the modern surface. To his dismay, he found that nearby Roman walls had been partly or completely robbed out, so that extension of the excavation would imperil adjacent houses. Over the next three years a combination of demolition and elaborate shoring gradually solved the problems of statics, but left the necessity of digging through several meters of fallen building material, a mixture of loose rubble and great chunks of solid wall. To maintain straight trenches, either horizontally or vertically, was impossible. An east-west section across the whole area has had to be pieced together out of two years’ work digging and the drawing of small stretches before they collapsed.

In clearing the southeast tower room, Jean Davison from the University of Vermont had to contend with the further novelty of digging from the bottom up, starting through a door reopened at Roman floor level into a space filled in from the top. Working by light from one bare bulb, in an enclosed space filled with dust from the dry, sliding fill, she contrived an ingenious set of sloping steps through the material, and excavated 750 cubic meters of earth in one season. It proved to be homogeneous building debris, and, like that in other areas, almost totally sterile of finds.

There is of course no place for such quantities of earth to remain within the city. From the tower there was direct access to the waterfront, and the police gave us permission to truck the earth away as we dug. It has been more difficult to remove earth from the area where John Wilkes was working. It adjoins the east palace wall on the other side of which is the public market. The earth is raised by winch to a window in the wall to be removed after the market closes at night. A full day’s work excavating building debris can mean trucking operations until three in the morning.

As the lower levels are reached, water comes in: sea water—the level of the bay has probably risen since the time of Diocletian—and leaking sewage. Except in one small room, we have always been able to reach the Diocletianic floors, but sometimes they remain underwater, and can be cleared only briefly, by hard pumping. Most disappointing was the impossibility of pumping sufficiently to examine the foundations of the southeast tower and the adjoining palace facade. Restored drawings of the palace show it rising from the sea like a palazzo from the Grand Canal. Winter winds dash savage waves into the harbor, and only an architect who did not know Split could have planned such a situation. We do not have any evidence that it ever existed. More of the southern facade will have to be cleared so more pumping can be done before we can find out.

In other areas we were able to study the foundations. They vary, depending on the nature of the ground beneath and of the structure to be erected. A wall built on or just above bedrock will have a shallow foundation just slightly wider than the wall itself. A similar wall resting on clay, where rock is far below the surface, will have a wider, deeper foundation. The foundations under the emperor’s Mausoleum and the southeastern tower are completely different. These buildings are heavy, tall structures, their walls consisting of a rubble core between inner and outer courses of ashlar masonry. For each a deep several-layered stone platform was constructed. The Mausoleum platform forms a great rectangle around the walls of the building, and is further secured by low retaining walls. At the points where the Mausoleum comes closest to those retaining walls, a further platform level was added. The builders were clearly concerned about the pressure of the walls and dome.

The size and preservation of the palace make it important for study of building techniques. The variety noted in foundations recurs in other facets of construction. We have been able to examine the heating systems in two baths: they use similar hypocausts (supports under the floor to allow warm air to pass underneath and warm the room) but in different arrangements. Romans made special types of bricks for their heating systems. Typical hypocaust tiles were found in debris within the palace, and flue tiles were used as drainage inlets, but not in the heating systems. There, the builders used standard materials ingeniously. Two drainage systems have been traced, one running underground outside the western bath, the other within the retaining wall of the Mausoleum foundation platform. We have also uncovered a variety of floors of mortar, tile, and mosaic; walls in two techniques previously known in the palace, and in a new one; fallen vaulting in which scaffolding traces could be studied; stone walls with mason’s marks, some already known in other parts of the palace, others new; walls which have retained the original plaster coating, which has totally gone from walls in the exposed parts of the palace. Construction will be studied by Michael Werner, the mason’s marks by Frederick Miller, the bath heating, drainage, and water supply system by Shirley Schwarz.

Evidence of the original decoration includes carved architectural ornaments, fine colored marbles for moldings and revetments, fresco fragments, and mosaic tesserae. One anta capital found near the bath is typical of decoration in the palace. It is covered by classical acanthus leaves, but arranged very unclassically, in that they are markedly asymmetrical. The asymmetry exists so that several small motifs can be inserted between the leaves on one side. These devices can be found in classical art, but never used in this way. The execution is painstaking. Throughout the carved decor of the palace we again and again find the use of classical motifs in a totally unclassical fashion, not through ignorance but through deliberate exercise of ingenuity. It is too early to say whether the impulse to change was aesthetic or symbolic. Study of the Roman fragments will be done by Ivan Mirnik.

Now the palace is monochrome: once it was full of shimmering color. The crystalline white, veined green and red and honey and purple of fine marble and porphyry imported from all around the Mediterranean decorated walls and floors, mosaics of glass and stone and gold leaf covered floors and vaults. No vault or wall mosaics remain in place but the small tesserae discovered by sifting Roman debris levels give abundant evidence of their existence. Nothing can be said about the patterns, but we can see the rich and subtle variations of color that were employed, including lavish use of gold leaf, a relatively new luxury, sparkling through the glass. The four mosaic floors in a courtyard off the east palace gate impress for quite another reason: their sloppiness. In each case, the execution begins carefully at one end, and then becomes much more haphazard at the other—the result of a master working alongside novice assistants? The mosaics, and the fresco fragments, will be studied by Claudia Smith.

The variety in construction and decoration appears also in plan, where one learns to expect the unexpected. Symmetry and regularity are present, but not as rules. There are several piers in the northern palace, and, on the same alignment, several more piers fifty meters away in the south. The piers are spaced in the same manner. Scholars had assumed that they could safely restore a continuous line of piers, all with a street in front and the same kind of rooms behind. In fact, there appears to be no connection between the groups. The two baths are located symmetrically in the southeastern and western palace, but their plans and construction are completely different, and so far as we can tell, neither one is itself symmetrical in design. The more we work, the more we realize how unsafe it is to generalize from any single find about practice in the palace as a whole, and the more we realize what a multiplicity of techniques there are to be studied.

What happened to Split after the death of Diocletian? A complicated picture is being pieced together out of evidence from each of our excavation areas. The eastern baths, discussed above, provide the most continuous picture, a chronological outline into which, fortunately, many other pieces can be fit. Almost immediately after construction, there was some basic change—the water supply for the bath was tampered with, the mosaic court was dismantled; then debris accumulated in many places; suggesting that a scanty population was huddling together in a small portion of the available area. We are anxious to know what building these people did, and how long Roman technique persisted, but evidence is incomplete. The first clearly identifiable postDiocletianic building—as yet not well dated—shows a complete break with Roman building methods, probably indicating that there were no longer skilled masons. Pottery too indicates a major cultural break. Then there is a rise in the standard of living, and probably an increase of population, which leads to a drastic improvement in building techniques, a reorganization of the city plan—the first since the palace was laid out—and, a little later, the reappearance of luxurious imported pottery.

This is a very rough outline, giving only the preliminary conclusions emerging as the jig-saw is put together. About strata and architectural remains we are fairly secure, but the pottery and small finds have still to be fully interpreted, a job made difficult by the great range of material, by the confusion in the stratigraphy, and by the fact that many important types have not been studied before.

Approximately four thousand five hundred pieces of pottery have been catalogued in five seasons. Its study is being carried on by Margaret Katris, Janet Buerger, and Emily Schwartz. Much of the pottery is coarse ware and medieval glazed ware, study of which is far less advanced than study of Roman fine ware. There are few uncontaminated strata in the palace, but there is stratified fill in a garderobe pit, in a dump between two houses, in layers between Roman and medieval floors, which can help in dating. Since 1969, all pottery has been retained, so that it can be reexamined as definition of significant types advances. In fact, a number of examples of important medieval fabrics have been recognized in “discard” bags and subsequently catalogued. The type series used for preliminary pottery sorting now comprises about a hundred varieties.

The Yugoslav authorities have permitted shipment of some pottery to the United States for study during the winters. The Graduate School of the University of Minnesota generously supports research. Much remains to be done. We hope that study of the coarse ware may solve one of the major problems of medieval history: when did the Slays penetrate into the coastal towns, which certainly remained Roman long after a Slavic kingdom flourished outside the walls? Which urban developments, if any, can be associated with the ethnic change? Up to now, discrimination of late antique from Early Slavic roughware has proved difficult, but Mrs. Schwartz hopes to be able to clarify the picture.

Study of fine ware is already telling us something about fluctuations in standards of living, and in trade connections. Fine Roman ware continues to be imported for several centuries after the death of Diocletian, then stops. For several centuries only coarse ware of local manufacture was used: Split was poor, and isolated. Then medieval glazed ware begins to arrive from Italy. The dates of the break, and resumption, of foreign trade, are not yet certain. In the early stages of our work it seemed that trade connections in the Roman and the medieval period were quite different. The Roman pottery came from the south and east, Africa and Syria, across the Mediterranean, while the medieval ware came from the northern Mediterranean coast, from Italy and Spain. This is certainly the predominant pattern, but the horizons of medieval Split are widening. This summer the previously complete lack of Byzantine pottery has been filled by a few examples, and there is even a plate from Syria.

Work in Diocletian’s Palace, geared to the pace of Urban Renewal, will continue for many years. This joint program is drawing to a close. We have done almost all the excavating we plan to do. Now we hope there will be several seasons of study and writing before the final publications emerge. A provisional excavation report is already in press: a second will follow, and then, several specialized reports. This work involves a large team of Americans and Yugoslays. It has been generously assisted by archaeologists and government authorities in both countries. I am sorry there is no room here to express fully our indebtedness to these people, and the satisfaction we have felt in participation in this successful cooperative venture. The work has many facets, and should contribute greatly to our understanding of Roman architecture in a critical period of transition, and of the processes of urbanization and ethnic change in the early Middle Ages

- Pottery from Split, local coarse ware, probably slavic.

- Pottery from Split, later medieval imported fine ware from Italy.

- Pottery from Split, imported roman fine ware.