Expeditions, especially archaeological ones, often produce unexpected results. The last Hasanlu Expedition was no exception. It started slowly with what seemed an interminable delay in the arrival of equipment, and the dull but necessary job of clearing away the accumulated debris of winter.

Having previously opened a number of graves belonging to people who had been buried with an interesting kind of grey-black pottery, we were anxious to explore the high “Citadel Mound” in the center of the site in search of their houses and whatever other remains of their Iron Age culture we might find. Their pottery, often in the shape of long-spouted pitchers, relates them to peoples already known farther to the east in Iran at Tepe Sialk (Kashan) and Tepe Giyan (Nihavand). Their culture appears to be the end of a long development which began back in the third millennium B.C. The problem of the origin and movement of this grey pottery is one of the most fascinating questions in the prehistory of Iran; and indeed, of Asia generally. Related wares are found as far west as Greece and as far east as the North China plain; but their relationships to one another elude is. The directions in which the potters moved, the time involved, and the identities of the peoples using the pottery are all subjects of speculation and research. At Hasanlu we have one of the paces where a late type of this pottery was being made during the “Dark Age” which preceded the establishment of the Median and Achaemenian Empires in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. Small wonder that our digging fingers itched to get started!

The Citadel Fortification Wall

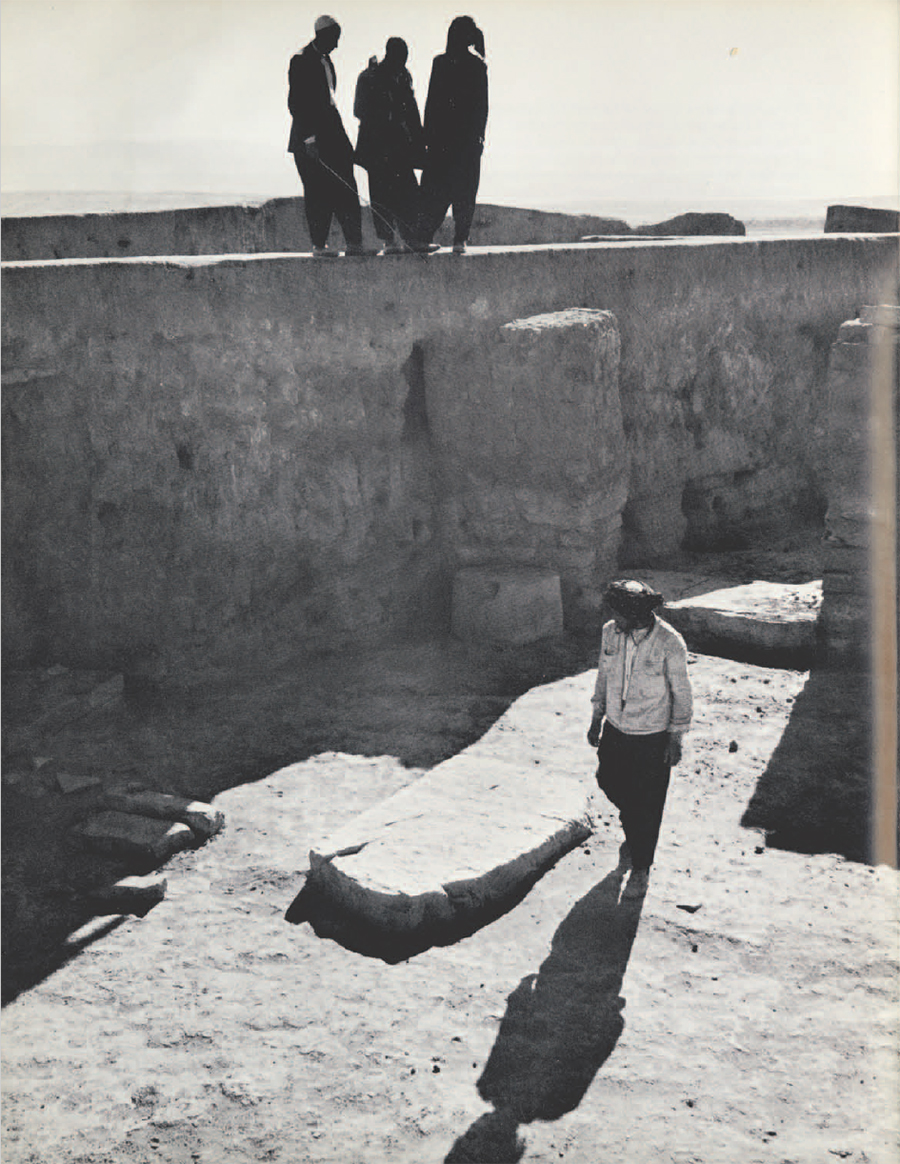

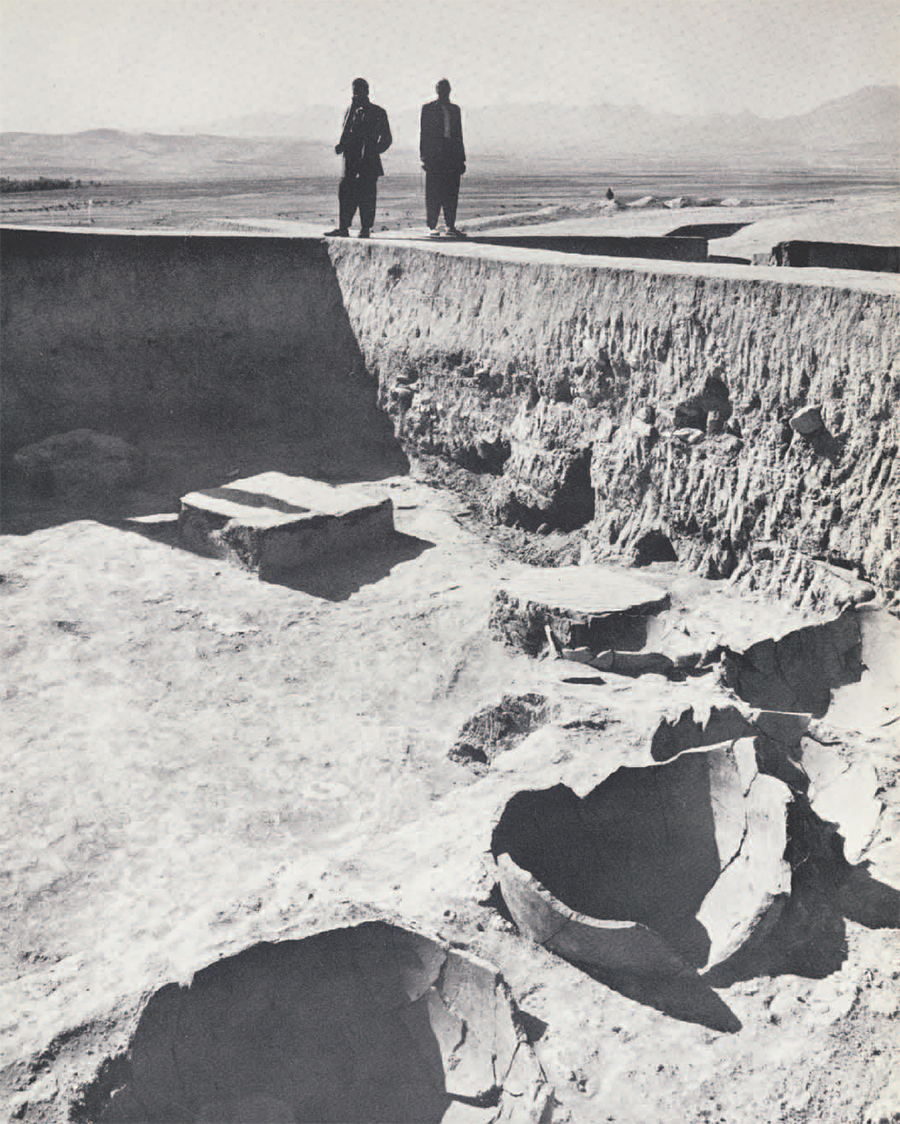

We began by taking a long careful walk around the op of the mound and discussing as we went the problem of what various surface bumps might mean, and how we were to dispose of the excavated dirt without piling it on the mound we were trying to excavate. Dirt disposal is a constant problem to the excavator, and more than one project has found itself bogged down through inadequate planning. The problem was not an easy one. The citadel is surrounded on all sides by the low Outer Town. This meant that we had either to surrender a section of the Outer Town, or to carry the earth down a thirty degree slope and across a flat to the distant edge of the occupational debris. As such a long distance clearly was economically unfeasible, we did the former, dumping down the steep south slope of the Citadel away from the prevailing northerly wind. The horizontal surface above this slope exhibited several interesting flat mounded areas surrounding the highest point of the mound (some seventy feet above canal water level). An exploratory trench the year before (Operation VII) on the north slope had indicated to us the presence of large stone foundations belonging to walls which encircled the Citadel, defending it from attack. Looking for these same structures on the southern side we now cut a northerly trench (Operation IX) in from the south slope. The new Operation sliced neatly through a mass of fallen burned brickwork at its northern end, and across a massive wall foundation at the other end. The foundation, built of large boulders and blocks of limestone, had once supported a high sun-dried brick fortification wall, over nine feet thick. The location of the foundation shows that the wall once encircled part, if not all, of the Citadel Mound.

At one of our regular morning tea breaks we held a conference on tactics and strategy, and decided to proceed with the excavation of a section of this wall while waiting for the arrival of our mechanical equipment. The advantage of this procedure was that we could dump onto the selected slope without having to pile mounds of loose dirt on top of the mound which would have required the wasteful use of our labor force endlessly moving sterile earth from place to place to get it out of the way. While this project developed, other teams of about ten men each made exploratory trenches on the southeastern and northeastern slopes in an effort to locate the fortification wall on these sides. Alas, the history of the mound was not so simple, and we recovered sections of a later wall, including a small gateway to the southeast, but nowhere the wall for which we searched. Our activities told us only that later and more poorly constructed walls existed above a burned level. The overall plan of our big wall remained obscure.

The section of that big wall excavated, however, turned out to be very imposing. It has four large towers spaced about thirty feet apart along its outer face. Between each tower a pair of rectangular bastions strengthen the main body of the wall. The westernmost pair flank a narrow entrance passage paved with huge slabs of limestone.As the local valley provides no suitable stone outcrops from which such slabs might have been obtained, we must imagine a continuous stream of wagons creaking across the plain for a distance of at least ten miles bearing heavy burdens of rock taken from the lake shore or mountains. Although none of these stones was cut or fitted except in a rough fashion, their size (some were six feet long!) and the volume of material used indicate the expenditure of a great deal of coordinated energy in the construction of the Citadel defenses. We may imagine the local governor or prince mounted on his horse at some high point on the mound directing the multitude of building activities. One wonders, of course, what occupied the Citadel before the big wall was built. Was it an older abandoned mound being reoccupied? Or had some previously prosperous town fallen to a new conqueror? The answers to such questions lay all summer in the soil beneath our feet, and await discovery with a new season of work.

The project now reached a critical point. We could not spend the rest of the summer chasing a wall–but as yet we did not have our wheelbarrows and other equipment. What to do? Before we could solve this problem, fate, in the form of a telegram announcing the arrival of our baggage at the railhead in Maragheh, eighty miles away, did it for us. At the same moment my assistant, T. Cuyler Young, Jr., arrived in the camp from a supply trip to Rezaiyeh wide-eyed with wonder. We too were wide-eyed when we climbed to the top of the mound and saw the tanks and trucks of the Iranian army rumbling through the twilight across our quiet plain!

The Iraq government had collapsed. With no radio ( a luxury our budget did not allow) we were reduced to reliance on our foreman’s reports on the outside world. It was an awkward predicament: unable to calculate the exact state of affairs, and unable to communicate with anyone in less than a week. Caroling Dosker, our Registrar and Camp Manager, Cuyler, and I conferred on what to do. I offered them the choice of staying of going. They voted to adopt our standard “Persian approach” to the problem; namely, to wait and see, because “something will happen–one way or the other.” So with that, Cuyler and I set off to collect the baggage–a simple four hour drive to Maragheh, a couple of hours to unload the equipment from the train, and a four hour drive home. A good day’s work, especially as visualized in the mind of the innocent westernet who knows that the secret of success is planning. And that well-laid plans work like clockwork. They do too–if you use the right clock!

All in a Day’s Work

We “began” leaving at six A.M. (the phrase is used advisedly for there is no such thing in the East as an instantaneous action; things do not “occur,” they come into a state of being and pass out of it again over an indeterminate period of time). At three P.M. we arrived at the deserted railway station after drowning the engine fording a stream and experiencing other little mechanical adventures. We could see “Cyrus,” our new truck, and the crates of equipment resting on a fiat car. At five P.M. the station master appeared and informed us in Persian that we couldn’t unload the flatcar without the receipt. The latter was in the possession of our second Iranian Inspector, Mr. Asgharion, who was nowhere to be found. We had already combed the town without finding him. “Oh.” announced the paunchy station master, “He will not be here until two days from now. I have a telegram for you!”

Armed with that bit of strategic information we trudged back to the garage where the one-eyed mechanic was prying into the engine of our antique jeep “Darius” by the light of a Coleman lantern. If we returned to Hasanlu we would be just in time to turn around and come back again! And the engine of the car was being most uncooperative. If we waited two days, Caroline wouldn’t know what had happened to us, as a telegram would not arrive at Hasanlu before we did. On the other hand, if we stayed, Tabriz, the “good garage,” and the Consul were “only a three hour” drive north. If we were to go there we could have a drink, a hot bath, see Mr. Josif, the Consul, and have the car checked. So, at nine P.M. we departed for Tabriz. At 9:15 we arrived back in town at the garage, having had more trouble with “Darius.” At ten we departed again for Tabriz where we arrived at two o’clock the following morning!

Two days later we were back at the station in Maragheh unloading our equipment from the train and putting it into a big truck. At nine o’clock that evening we started for Hasanlu, exhausted and unhappy about our three day absence. At one A.M. as we approached the town of Mahabad we were arrested at rifle-point by the Iranian army which had reimposed travel control and didn’t know who we were. At ten the next morning, after a cold night in the car and after being interviewed by numerous officers, the commanding general finally allowed us to proceed to Hasanlu where we arrived in time for lunch. All in a day’s work!

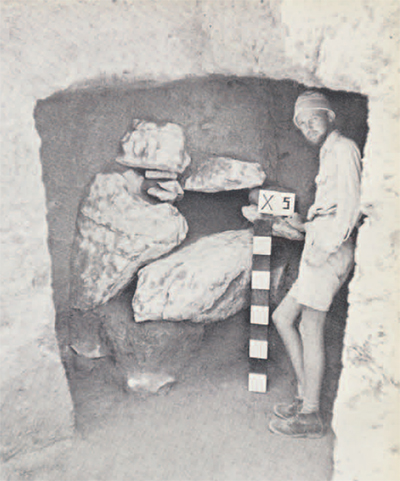

With the equipment at hand, and the staff reassembled, the expedition was now able to turn to with real enthusiasm. The Operation tracing the wall was concluded, and the process of clearing the quadrant enclosed by it (which contained a burned structure) was started. A grid of eleven-meter squares (XXI-XXI-XXVI) was surveyed to provide controls in digging area by area. Such a procedure insures adequate supervision of the workmen, while the vertical sections visible on the balks after excavation act as checks on the accuracy of the stratigraphy determined in digging. At the same time, besides two soundings in nearby Chalcolithic mounds, we carried out an additional sounding in the Outer Town. This latter Operation (X) confirmed our previous conclusions that the Outer Town dates back to about 2000 B.C., and also provided our first rock tomb.

The Citadel: Late Remains

In the aerial photographs, and on the ground, traces of walls and towers belonging to a late fortification may be seen on top of the mound. These belong to a structure of the Islamic Period as indicated by the type of small square brick found just under the present surface. Below the shallow remains of this eroded brickwork the soil is disturbed by various deep pits filled with grey rubble—testimony no doubt to the erratic activities of former treasure hunters. In two instances we came upon solitary skeletons resting in stone-lined graves. Graves of this type are abundant at Ashur and Babylon during the Parthian Period (249 B. C.—A. D. 226)—the equivalent of the Roman Period in the west. At this time, it would appear, the settlement at Hasanlu was elsewhere than on the Citadel Mound. Fragments of glass found in the vineyards to the south suggest its possible location

The graves themselves lay in the debris of an earlier period represented by wall foundations and floors. These belonged to houses which had been built against the Citadel Wall following its restoration with a strengthened West Gate after a period of abandonment. To this general time also belong a small Postern Gate on the southeastern slope, fragments of defensive walls on the east and north slopes, and a house with a paved courtyard in the Outer Town. All of these buildings with their more-or-less square rooms sprawl unevenly over the areas they occupy. They were constructed of mud brick set on foundations of roughly squared stones, many of which had been taken from earlier structures. None of the fine grey pottery known from the cemetery was found in this level. Instead, we discovered potsherds of a thin orange-buff pottery with a high polish, decorated with hanging triangles in a purplish-brown paint. In type of finish, fabric, shape, and in one case pattern, these sherds may be most closely compared with those we collected from Ziwiye in 1956. This latter site lies some distance south of Hasanlu in Kurdistan, and is the source of the famous Ziwiye Treasure (several pieces of which we have in our Museum collection). One vessel of well-polished red pottery was also found. This is of a type known from the Urartian site of Toprak Kale near Lake Van in eastern Turkey where it is dated to the middle of the eighth century B. C. A similar date has been suggested for the Ziwiye materials. It would seem reasonable, therefore, to suggest that, on present evidence, the later remains at Hasanlu also ought to date to the eighth century or later.

The Citadel: Period of the Burned Building

As our wheelbarrows hauled away the debris of the later occupation it became apparent that the underlying Grey Ware Period had ended abruptly with the sacking of the city. The intensity and suddenness of this event were demonstrated by the masses of fallen, partially burned brick which filled rooms and was heaped against the Citadel Wall, and by the distorted bodies of men trapped in the collapse. We now realized that similar conditions in a house in the Outer Town excavated last year, and many evidences of burned soil around the site indicate that the entire city had been put to the torch. By whom we do not know. The significance of the period of abandonment which followed became clear: the bronze casters, the pottery makers, the builders of the wall—all had died in the flames, had been slaughtered on the ramparts, or had been carried away into slavery. The manufacture of polished grey pottery ended abruptly; no survivors searched the ruins for the treasures left there; no townsmen were buried again in the cemetery with their bronze and iron jewelry. A way of life had ended. In the succeeding days of silence the wind and rain had eaten into the ruins, packing down the debris and piling it against the Citadel Wall.

Photograph by Loomis Dead courtesy of Life Magazine

The Burned Building: Palace or Temple?

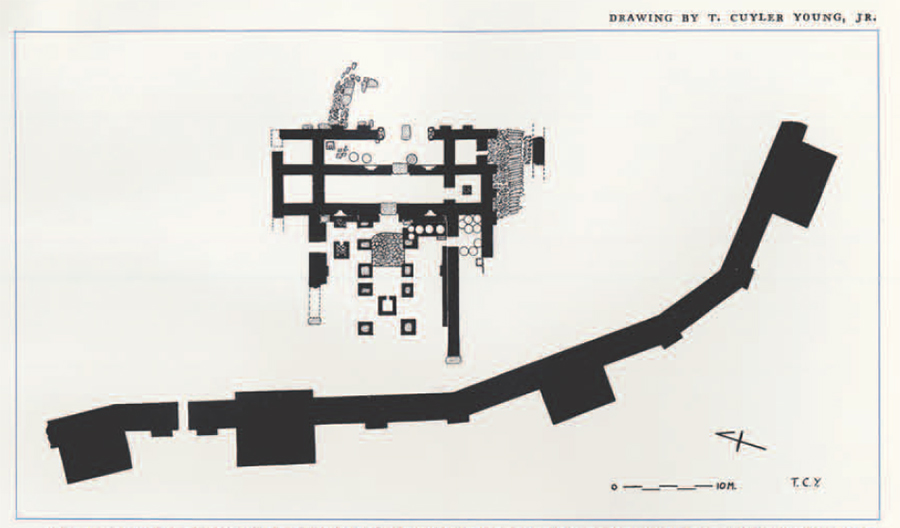

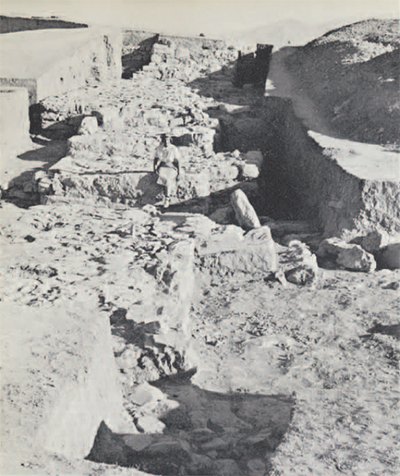

From under a mantle of red dust and fallen brick emerged a large building facing a big courtyard or street which once had been paved with slabs of sandstone and limestone. The eastern façade of the building, over eighty-four feet in width, is broken by a central doorway some twenty feet wide. The outer wall on either side is divided by pilasters into three equal sections. The entrance itself is subdivided by the limestone base for a central lintel support. Similar supports of red sandstone lay at either side of the door at the base of the jamb. The outline of a pair of round columns can be seen on the surface of each, while their impressions are preserved in the mud plaster facing of the walls. The walls flanking the door are still standing to a height of over six feet, and the door was undoubtedly higher still. The volume of brickwork filling the rooms indicated that we were dealing with what had been a two-story structure. This inference was upheld when we drew the section of the balk, as well as by the discovery of many objects on a collapsed floor above the ground floor.

Looking through the main entrance, one faces across a long narrow room toward a smaller doorway with a large limestone sill. The door is flanked on either side by a crenellated niche built into the brick part of the walls above the free-standing stone foundation. The large square bricks are like those found at Hamadan and Persepolis in buildings of the Median and Achaemenian Periods (seventh to fourth centuries B.C.). To the left of this doorway stands a round stone drum. At first we thought that this might have been a column base, but closer inspection showed that the front edges are highly polished from wear. We concluded, therefore, that, while it could have served at some time as a column base, in its present location it must have served some other function. Equally mysterious is a brick-edged hole in the floor at the opposite end of the room. Sitting in this opening was a large pottery jar decorated with raised spirals. The spiral pattern was a surprise as it has been assumed to be characteristic of the Early Bronze Age. We now know from this example, and others, that it was also being used in the Early Iron Age at Hasanlu.

Passing through the small door, one leaves the East Room and enters the parallel West Room. Ahead lies a similar door leading through to be West Court. All three of these doorways, like those in the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, are sufficiently out of alignment to prevent an easy view from one court to another. At each of the shorter ends of the West Room a narrow doorway leads into a small adjoining room. The northern of these doorways had been blocked up with mud brick while the building was still in use. The isolated room was quite empty, but its counterpart to the south is furnished with a small stone podium or table. This feature, together with the use of niches, suggests a religious function of some sort, but does not provide sufficient evidence on which to base concrete conclusions. The main West Room was otherwise quite plain and no doubt quite dark, as it relied primarily upon light reflected from its white-washed walls for illumination.

We discovered with interest that the East Room was also bordered to north and south by a small room. Strangely enough, these little rooms could be entered only from outside the building. Not only that, but they were very small with exceedingly narrow entrances. The southern, or Refuse Room, was filled with black organic soil and animal bones, mainly sheep or goat, and broken grey ware saucers or dishes. There was no indication of how this refuse had entered the room—whether through a hole in the wall from the Podium Room, or through the ceiling from the second floor. The selective nature of the material suggests that the room had a special function, but whether it was simple kitchen refuse or some ritual by-product we could not determine. The room on the north also had rich earth on its floor and some bones, but not as many, and the less abundant pottery was of no special type. The narrow entrances were obviously to permit periodic cleaning.

The West Court filled the area between the building and the Citadel Wall. It was a simple roofed-over structure, one story high, with side walls set on a single course of small stones. Light and air were provided through a central opening in the roof, indicated by a paved area on the floor equipped with a sunken storage-jar drain. Storage rooms entered by small doorways flanked the court on the north and south. The South Storage Room had had a wooden door mounted on a stone door socket. The fact that the walls of these storage rooms are slightly out of alignment with those of the main building shows that the court had been added as a separate unit. Its roof was supported by a double row of wooden pillars set upon stone slab bases. The exit from the West Room is flanked on either side by a pilaster which, in turn, flanks a crenellated niche of the type already described in the East Room. The pilasters are in line with the two rows of pillar bases. A clay bench had been built around three sides of the court against the walls. In the center of the northern section of the court is a small hearth of paving stones surrounded by a low mud wall. The bench in front of this has a built-in surface of paving stones set directly in front of the niche and running down the face of the bench to a larger rectangle of paving stones on the floor. Nothing lay beneath these stones. The section of the bench in front of the other niche, and the niche itself, had been obscured by the construction of a much wider mud platform into which a number of large storage jars had been set. These apparently held some sort of liquid, most likely beer or wine, as indicated by the remains of pottery funnels on the floor, and by the rings on the inside of the jars marking the level of the contents at the time of the fire.

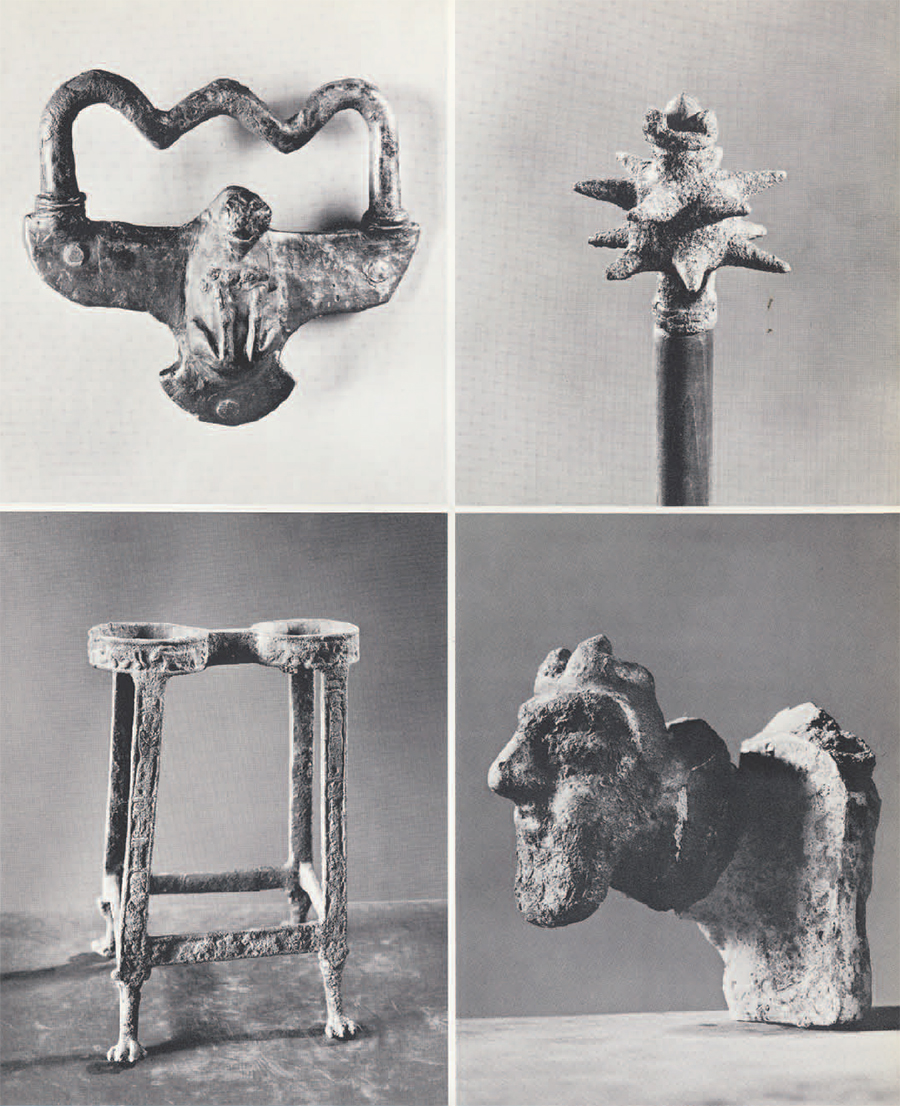

As we dug down into the debris we came upon a mass of iron lanceheads and fragments of sword blades lying in the uppermost part of the fill—perhaps from the roof. Farther down and under collapsed brickwork we found the remains of quantities of objects which had been housed on the second floor. The East Room alone produced almost two hundred. These include a rich variety of carved stone bowls, copper vessels and pieces of paraphernalia, fine polished pottery jars made in imitation of metal shapes, domestic pottery, beads of carnelian and glass, bronze maceheads, bronze buttons, and fragments of a bronze lion figurine. A number of these objects were identical to those excavated in the late graves of the Grey Ware Cemetery; so we knew at once that we had found the buildings which belonged to the people buried there.

Among the more interesting objects were fragments of glazed wall tiles. One of these is in the style of ninth century Assyria. Another is decorated with a unique human head in the round. Another prize is a bronze stand with four animal claw feet and a double ring top. It is decorated with raised animal and human figures. All of these items have now been added to our Philadelphia collection where they are being cleaned and studied.

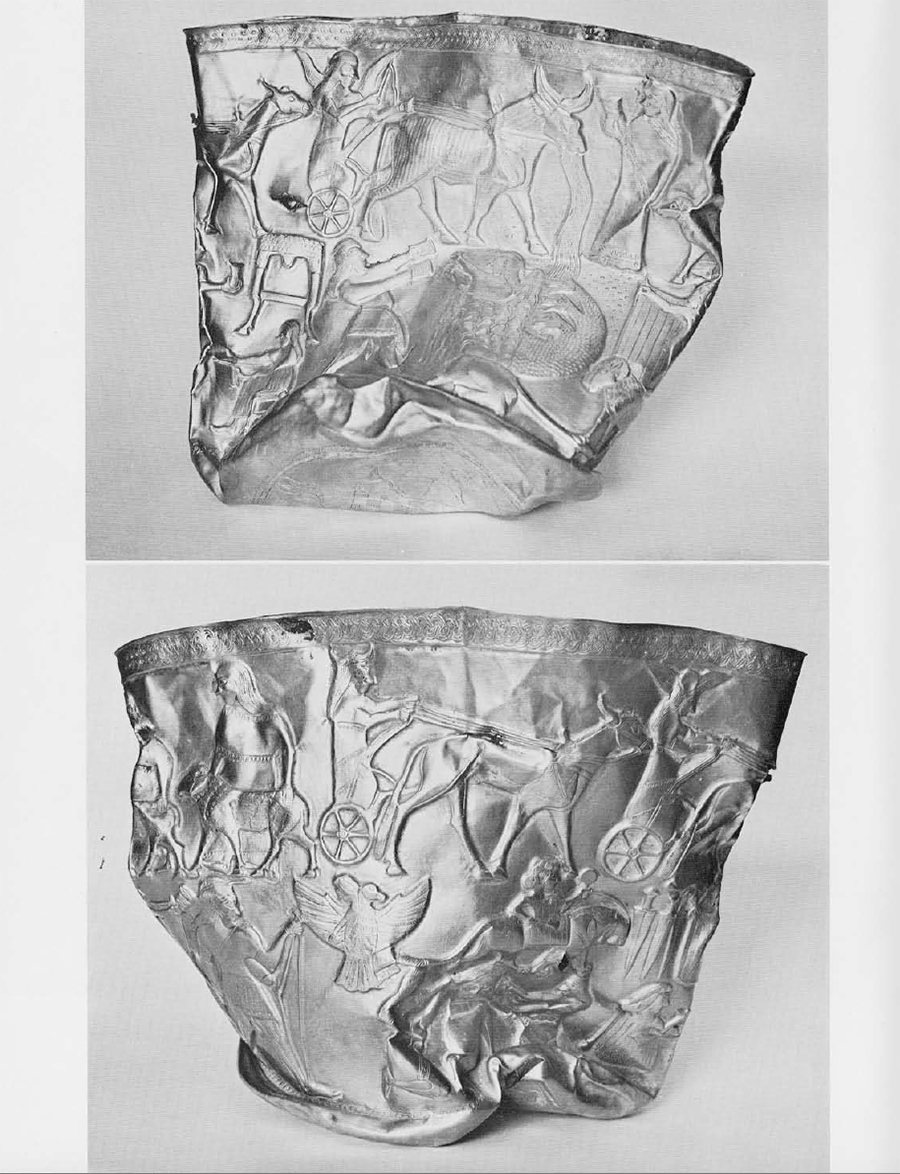

Still another beautiful piece is a silver cup, about eight inches in height, decorated with two registers of applied electrum figures. The upper register represents a victory scene with a chariot, prisoners, and soldiers; the lower, a lion and horse in heraldic opposition flanked by archers. The cup, like the bronzes, has not yet been cleaned and cannot at present be adequately illustrated. One interesting point, however, is that it had been stored away wrapped in cloth, the impression of which is preserved in the surface corrosion. The style of the decoration is totally different from that on the other major art treasure recovered, the gold bowl.

This latter object, which we propose to call simply the “Hasanlu Bowl,” is eight inches in height and eight in original diameter. It is made of solid gold about 3/ I 6ths of an inch thick, and weighs over two pounds. From the position in which it was found in the Refuse Room, it is clear that it was being carried out of the flaming building by one of three men who were on the second floor at the moment it gave way. The leader of the group fell sprawled forward on his face, his arms spread out before him to break the fall, his iron sword with its handle of gold foil caught beneath his chest. The second man, carrying the gold bowl, fell forward on his right shoulder, his left arm with its gauntlet of bronze buttons flung against the wall, his right arm and the bowl dropped in front of him, his skull crushed in its cap of copper. As he fell, his companion following on his left also fell, tripping across the bowl carrier’s feet and plunging into the debris. The weight of the walls and the suddenness of the collapse were so great that the edge of the third man’s jaw was driven through the upper end of his arm like a knife, and remained in that position when we unearthed it. He carried an iron sword and a star-shaped macehead of bronze mounted on a wooden handle. His tunic was fastened at the neck with a simple copper pin.

With the finding of the bowl, life became very complicated. Interest in the contents of the mound went up sharply in the village, and the need for greater security became urgent. During the following days while Charles Burney, our British colleague, and Mr. Assefi, our Iranian Inspector, were drawing the vessel, we were joined by two soldiers who pitched camp on the mound and patroled the house during the night. The story was told in the villages that a great serpent lived in the mound, and that it was unsafe to go there after dark!

Problems

The discovery of a large building with so many objects raises multitudes of questions which only long, patient research will begin to solve. The foremost of these, of course, is the date. This must be determined by collating the various lines of evidence: the stratigraphic position within the site, comparison with objects unearthed elsewhere, analysis of art style and iconographic content, analysis of carbon samples for radiocarbon dates, and the exploration of historical records for possible events related to the archaeological reconstruction based on the material culture. This is a long process and the conclusions at which one arrives apt to change a number of times before a final answer which satisfies all the evidence is found. The analysis in this case is made more difficult by the fact that many of the artifacts are distinctive and do not lend themselves readily to comparison. The pottery in general ties the Burned Building and the Cemetery together, and connects them both to west central Iran where related pottery dates from 1000-800 B.C. The finer pottery types, found only in the building, suggest the possibility that the rulers of the town had a more special taste connected with a history somewhat different from that of the ordinary citizens. The types are certainly unique enough to justify a thorough inquiry into this line of investigation. At the same time, other objects seem to point to cordial relations with Assyria during the ninth century B.C.—a high point in early Assyrian power. Nothing indicates trade with Urartu, Assyria’s rival in eastern Turkey. Three radiocarbon samples from the burned stratum elsewhere on the site have produced dates of 807, 813, and 923 B.C. These dates and typological comparisons suggest that the sacking may have taken place toward the end of the ninth century B.C.

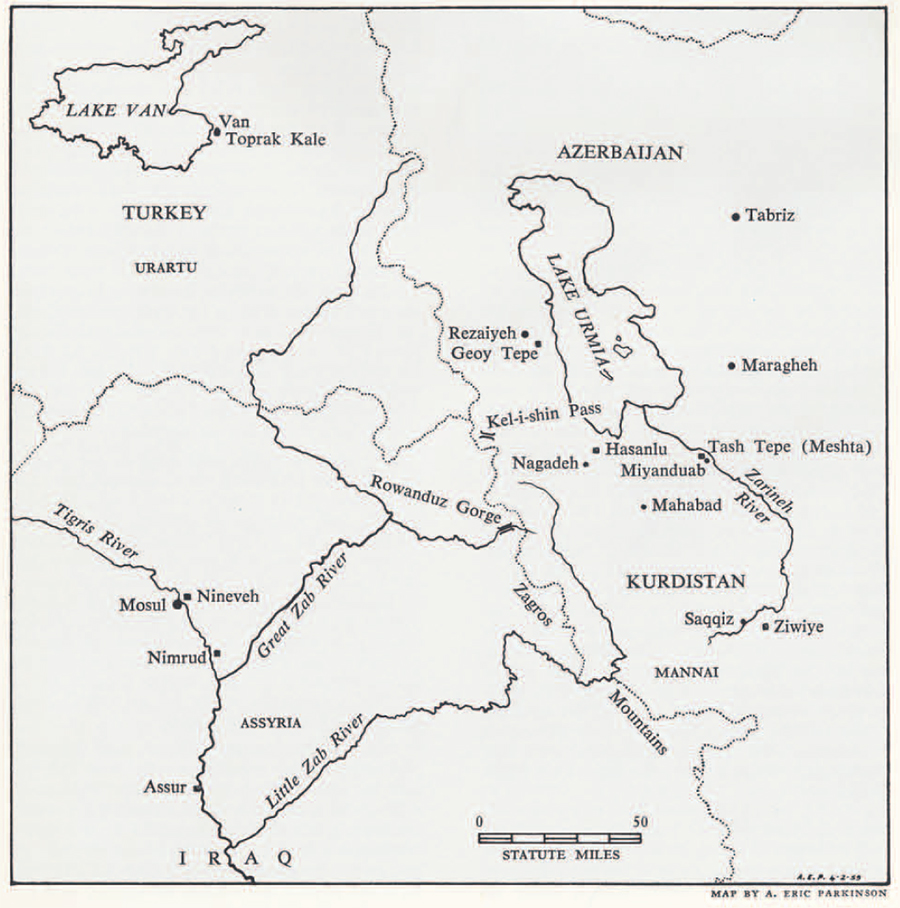

If we look at the historical records of this general time range in an effort to discover what kings are known to have campaigned specifical1 in this area, we find only one clearly documented candidate: Menua, King of Urartu. This king, while ruling jointly with his father Ishpuini, set up an inscription sometime between 815 and 807 B.C. near the city of Musasir in the Kel-i-shin Pass, about twenty-five miles due east of Hasanlu. During a period of Assyrian weakness a few years later, between 804 and 790 B.C., the same king when ruling alone set up a victory monument at Tash Tepe about 50 miles west of Hasanlu on the south coastal plain of Lake Urmia near the modern town of Miyanduab. This inscription celebrates the conquest of the Mannaean city of Meshta. The local geography and the location of these two inscriptions clearly indicate that Menua passed by Hasanlu sometime at the end of the ninth century. Such an event might well have been the cause of the holocaust which engulfed the city. It is interesting that, while numerous articles suggest Assyrian influence before the fire, nothing found so far makes such a suggestion for the later levels. On the contrary, at least one vessel points toward Urartu. After Menua, the next candidate would be Sargon II of Assyria a century later. At present there is nothing to suggest such a late date and we are left with what appears to be a perfectly plausible hypothesis in regard to Menua, but without adequate data upon which to base any firm conclusions.

It is to be understood, of course, that a date for the burning of the city does not give more than an ante quem date for the silver cup and the gold bowl—which are no doubt older. Indeed, the Grey Ware Period itself had a reasonable duration as indicated by the depth and superimposition of graves in the cemetery, and by the fact that the functioning of the burned building itself had been altered through the blocking of a doorway and the building of the storage-jar platform. How long did this Grey Ware Period last? Two radiocarbon dates give us an indication: one from below Burial 13, a deep Grey Ware burial in the cemetery, gives a date of 1025 ± 12 B.C.; while another date, from the stratum underlying the Grey Ware on the Citadel, gives 1042 +- 120 B.C. These, and the dates previously mentioned, suggest a time range of slightly less than three hundred years for the Grey Ware Period. Such a range is not inconsistent with the dates estimated for related materials elsewhere in Iran.

More Problems

The lot of an archaeologist is not an easy one. Especially when the public interest is aroused. Our first inkling of this fact came from reports received at the site from visitors. The story of our golden bowl reached Nagadeh, our market town seven miles away, and then swept up the valley. By the time it came to an end the beautiful bowl had been changed into the king’s solid gold desk! The cable wires buzzed, and our quiet telegraph office blazed into action! We received the first telegram ever written in English by the operator. It provided great sport at morning tea when we read:

MOWS ROLOUSO OUR TOMORROW PLOASE HOLD ALL PICTURES FOR LIKA OXCLUSIVO ALL HORO DOLIGHTODFRA.

A little thought translated this into—

NEWS RELEASE OUT TOMORROW. PLEASE HOLD ALL PICTURES FOR “LIFE” EXCLUSIVE. ALL HERE DELIGHTED.

[SIGNED] FRO.

We were enchanted! At the same moment the telephone from Philadelphia to New York was buzzing, and in a short time a well-intentioned cable was on its way to Paris heralding our modest discoveries. “Fabulous ancient city dripping with gold…was the startling beginning of the unrecognizable story contained in the cable which was thrust into our hands by a weary photographer at the end of a two-day marathon around Azerbaijan trying to find us. Needless to say, we had been on one of our “four hour” drives to the railhead to meet him in response to a telegram which “superceded” a previous message which we had never seen. (But wonders of the East! It was delivered two days later at the bank in Tabriz only a hundred miles away from the address!) None of us had yet seen the “news release” referred to in Dr. Rainey’s cable, and we developed what may best be described as a “dripping city” chill at the thought of the interpretations possibly given to our reports home!

It was not until a week later that the complete state of mental anguish which now engulfed us was dispelled in Tehran by the arrival of the news story as it had been released by the Museum and had appeared in the American press. We heaved a great sigh of relief and prepared for the journey home. Of such stuff is fieldwork made, and expeditions are rounded with their news release—especially when a bowl is golden.