A scattering of representations and ancient written references, ambiguous or unhelpful when studied separately, reveal when brought together a not fully realized aspect of life in the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.: the Greeks and their contemporaries the Etruscans practiced high diving into the sea.

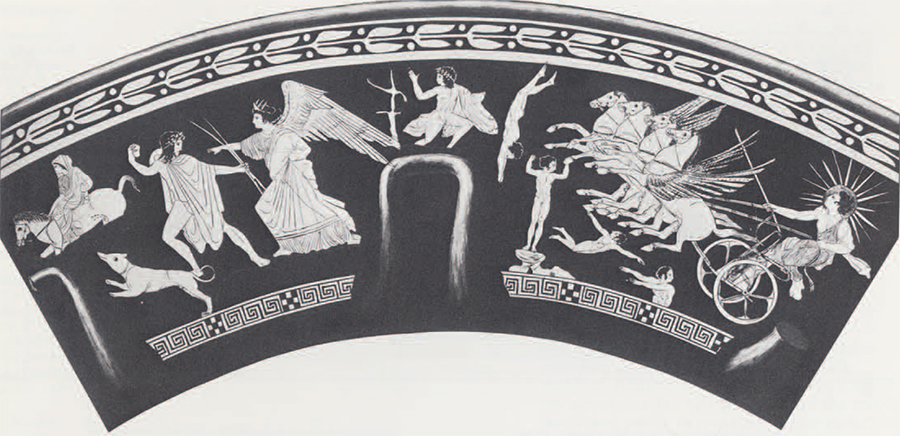

At its most daring the diving was done from cliffs, like that which boys undertake for tourists at Acapulco today. The cliff diving can be seen most readily in a tomb painting of the late sixth century at Etruscan Tarquinia, in which a boy plunges down from a high rock outcropping in the sea. Dim contour lines partly obscure another representation of the sport in an Attic vase painting of the late fifth century: as minor figures in a depiction of the pursuit of Kephalos by Eos (Dawn), two boys swim in the sea while a third is poised to re-enter the water from a low protruding rock and a fourth dives headlong down along the cliff face at which the body of land to the left ends.

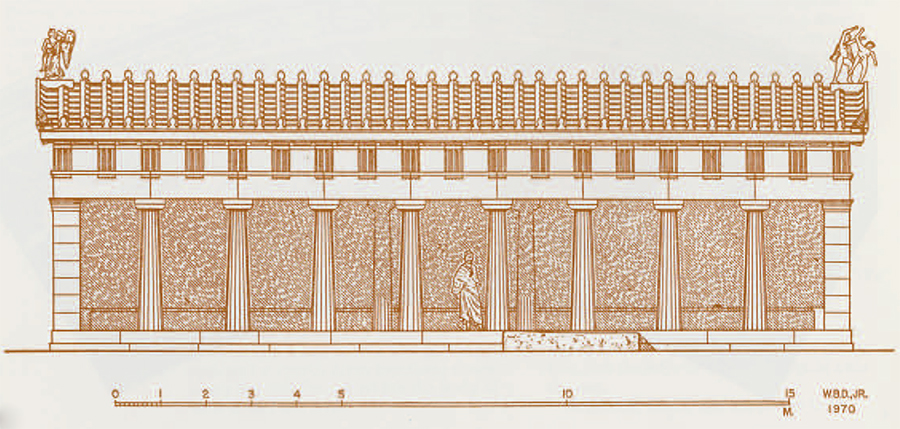

The hero Kephalos is shown hunting, as often in the iconography of the time, but one can suspect from a further representation that a tradition of him too as a diver, attested in a perhaps confused form some centuries later (Strabo X, 2,8), may already have been current in the fifth century, or that, at a minimum, his adventure was regularly set at the sort of precipitous shoreline seen in the painting. Terracotta statue groups added as akroteria (peak ornaments) to the Stoa Basileios in the Athenian Agora in the middle of the fifth century B.C. portrayed Eos and Kephalos at one end of the roof and Theseus and Skiron at the other. The encounter of the latter pair is well known: Theseus threw Skiron into the Saronic Gulf from the cliffs separating Attica and the territory of Megara. It would be appropriate if the understood setting for Eos and Kephalos would convert the roof end of that group, too, into the edge of a high precipice over the sea.

Kephalos’ home was supposed to be Thorikos, only about six miles from Cape Sounion at the southern tip of Attica, an area with suitable cliffs for the sport.

A pair of written sources roughly within the time span of our representations have something to say about cliff diving. In his play Cyclops of the late fifth century, Euripides has the satyr-chief Silenos remark:

“I’m mad to drink a cup of wine … and once good and drunk to throw myself into the old brine from the white rock.”

The implied point, that cliff diving is something to do when drunk, looks to have been a commonplace, since it lies behind a figurative allusion by the East Greek poet Anakreon a century earlier:

“Drunk with erotic desire I dive from high up on the white rock into the gray waves.”

One can understand the viewpoint of the adult spokesmen about the sport needing the spur of drunkenness. In addition to the sheer drop, unnerving under the best circumstances, the diver faced the danger of smashing himself on the cliff if it had anything of an outward slope and he did not clear it properly. It is good, though, to have gotten from the representations another viewpoint recorded, that of boys, who presumably needed no exhilaration other than the dive itself.

In the written sources of later antiquity, beginning at the end of the fourth century B.C., there are further but not very helpful references to cliff diving. The practice somehow came to be believed as something that had been done by a long series of historical and legendary figures, including Kephalos, exclusively as a charm for overcoming romantic longings, the authors’ belief perhaps stemming from a misunderstanding of passages like the surviving scrap of Anakreon. And it may have been an unimaginative interpretation of the conventional poetic expression “white rock,” leukas petra, as occurring in both the Anakreon and the Euripides passages, that led to an identification of the peninsula of Leukas in northwestern Greece as the place where all the diving had been done. The confusion of the later writers probably betrays that the sport was no longer current.

Even back when cliff diving was done, however, in the sixth and fifth centuries. it was not the only kind of diving practiced. An alternative that eliminated the problem of a sloping rock face was the use of an artificial high stand set at the water’s edge. Such an arrangement is known from two representations. In an Attic vase painting of the late sixth century a party of women bathers dive from a stand built up in three parts: a broad, fairly high base, a central dado of about human height (if one can judge from the wildly fluctuating scale of the figures), and a slightly projecting top course. In a tomb painting of about 470 B.C. at Paestum in Greek Southern Italy a boy uses a plainer structure with a single rise and a platform on top with more of a projection out over the water. The Paestum stand gives the impression of being higher than the Attic.

A diving stand would, of course, be safe only on a beach where there was an immediate drop-off beyond the water line. A shelf of land at the end of a cove along a cliff-lined coast seems likely to have been the most favorable sort of location, and such is, in fact, the apparent setting of the vase painting: the irregular side borders with trees growing from them represent cliffs hemming in the narrow beach. It may be that the Paestum painting has schematic indications of a similar setting. The tree growing from the right border may signify that the side, though straight, is meant to double as a cliff face, and the tree to the left might mark the position of an opposite shore bounding the none too broad waters of a cove.

Platform diving may seem tame when compared with cliff diving, but as the equivalent of diving from a high board at poolside, it was a sport that modern swimmers will recognize as challenging enough.

- Cover slab from Tomb of the Diver, late 6th century B.C., Paestrum. (Courtesy Soprintendenza alle Antichita Salerno)

- Cape Sounion. (From V. Scully, The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods, New Haven, 1962, fig. 291; courtesy Yale University Press)

- Cliff diving at Acapulco (Courtesy Mexican National Tourist Council)