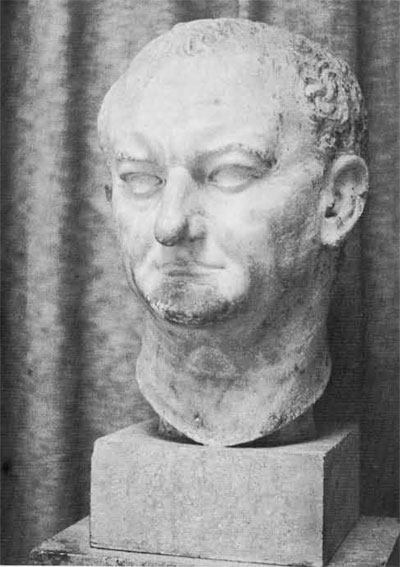

Titus Flavius Domitianus–a handsome man, graceful of carriage, rather tall in stature, quick witted and intelligent though not well educated in the liberal arts, somewhat flushed in complexion and certainly over-sexed; this was Domitian the son of an astute, cheerful, country gentleman and the grandson of a most respectable provincial government tax-collector and banker. By chance and the armed decision of the soldiers whom he commanded, Vespasian, Domitian’s father, had become a ruler of the entire Roman world. This was a most unexpected and, to some extent, an undesired development for the realistic and unpretentious Vespasian who had managed, somehow or another, to avoid seriously antagonizing the egotistical emperor Nero. It was Nero who had appointed Vespasian to command the military suppression of the Jewish revolt in Judaea. Nero’s pitiful but perhaps appropriate suicide had thrown the Roman world into the nervous hands of three successive rulers within less than two years. But finally the Roman forces in Egypt and Judaea had thrust Vespasian into the imperial purple. Unfortunately this down-to-earth citizen was busily engaged in the foreign war at the time and it was left for his younger son Domitian to take over the reins in Rome for the time being. The older son Titus was in Judaea and deeply involved in his father’s projects for the conduct of the war.

Domitian, for a matter of months, had found himself acting in Rome as regent for his father until Vespasian could return from the East to assume his throne. For a youth of only eighteen this was a heavy portion of responsibility and Domitian enjoyed his authority to the utmost; when Vespasian at last reached Rome he found occasion to reprimand Domitian for his unseemly arrogance and made it clear that he considered his other son Titus to be far more dependable.

Ultimately Vespasian died, joking with his last gasp of breath, and Titus did succeed to the throne. But the new emperor’s charm and forbearance failed to alleviate Domitian’s feelings of resentment at having been relegated to a secondary position. When Titus died the empire at last passed to the hands of Domitian and there remained no one in the family who dared restrain him. From a willful child born to a crude, unaspiring father Domitian had grown through young manhood in near-poverty, with a poor education, yet able to secure passing attention by virtue of his good looks. Late in his teens he had been nearly murdered in the revolution which culminated in his father’s assumption of the imperial dignity. Then for a brief while during his father’s absence he had been given almost absolute authority in Rome–and he had proceeded to enjoy this power in a whirlwind of self-indulgence; he engaged in liaisons with numerous women, married and unmarried, and lavished government appointments on countless numbers of men. He even began preparations for a military campaign into Germany to rival his brother Titus who was finishing the war in Judaea. This burst of egotistical energy lasted through the months until Vespasian entered Rome to take imperial affairs into his own hands. Then Domitian found himself shunted into the background to sulk for eleven years.

This was the man who, in A.D. 81, became Roman emperor and it is not surprising that he had every intention of using his power as he wished. Though at first self-assertive yet scrupulously fair in the administration of justice, he became a frightening autocrat after the quelling of a rebellious attempt to eject him from the throne. The Senate, its authority already greatly diminished by early emperors, was largely ignored and even insulted by Domitian. As a further sign of his superiority Domitian established the custom of having himself addressed as Lord and God (Dominus et Deus). Though it was the ancient custom in some lands of the eastern Mediterranean to view their living rulers as gods this was alien to Roman practice. With Caesar’s death the Romans had accepted the concept of deifying a deceased emperor but the action was dependent upon a favorable vote in the Senate. The emperor Caligula had attempted to represent himself while alive as worthy of a godhood but Domitian broke all precedent for Roman emperors in the new title which he required from all who wrote or spoke to him. To embellish this exalted position he lavished vast amounts of money on a new palace, new public buildings, extravagant Saturnalis parties, entertainments for the populace, pay increases for the soldiers, and outright monetary gifts to the citizenry of Rome. But, while the soldiers supported him, the citizens remained neutral and the Senate detested him.

On September the eighteenth of the year A.D. 96, between ten and eleven o’clock in the morning, Domitian withdrew to his bedroom for an emergency interview and there found himself confronted by a well-organized group of palace conspirators who had even secured the support of the fearful empress Domitia. Grappling desperately with his murderers, his fingers slashed to the bone by their knives, Domitian collapsed and dies with seven gaping wounds in his body. Unceremoniously rushed out of the palace by undertakers of the lowest class, the corpse was cremated by Domitian’s loyal nurse in her own little suburban place on the Latin Way; then she secretly carried the ashes to the emperor’s family shrine on the Quirinal hill and mixed them with the remains of his niece for protection.

The announcement of Domitian’s death roused little feeling among the populace. The military forces in the capital were outraged at the murder and proclaimed that, as a deceased emperor, he was now properly in the realm of the gods and should be acknowledged as a god himself. This decision, however, was a purely political matter to be determined by the Roman Senate and no one else. And here Domitian died a second death.

Thoroughly delighted with the news of the assassination the senators held a special session in the senate house and there vilified the dead emperor in words unworthy of their own dignity. By vote they refused to elevate his soul to a god-hood and, going to the other extreme, they ordered that all reminders of him should be removed from public view. His statues were to be destroyed and his name erased from every inscription throughout the empire. In this month of September, A.D. 96, Domitian’s memory was condemned.

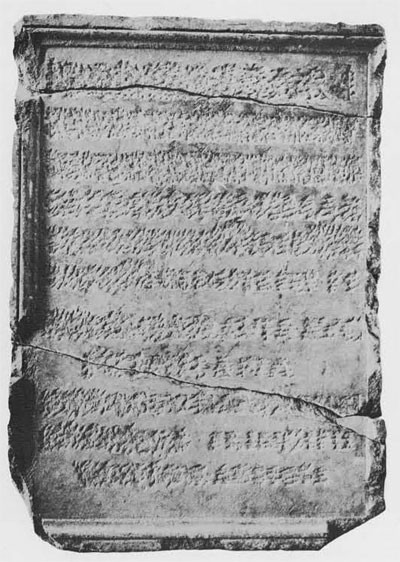

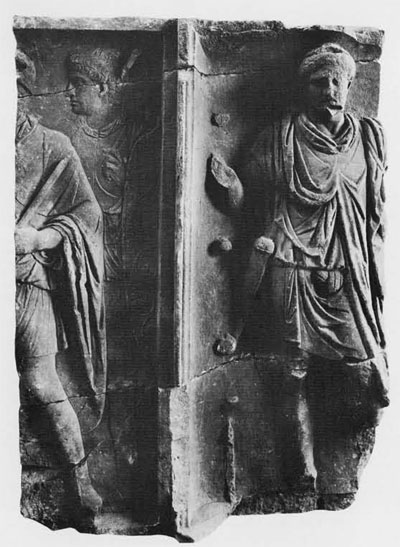

During the year 1909 Italian workmen preparing the foundations for a new house in Pozzuoli near Naples, on a site about 150 meters southwest of the ruined Roman amphitheater uncovered portions of a bas-relief in marble. When pieced together these proved to form a segment of a relief representing Roman soldiers. In 1910 this was purchased and delivered to the University Museum in Philadelphia. In subsequent years many scholars have been attracted to this relief and from their assiduous studies have come additional bits of information. But all understanding of the object must take into account the fact that, while it has the figured relief on one side, the back of the stone bears an inscription which was erased in antiquity. It has been generally accepted that the stone was used first with the inscription side showing–perhaps at the base of a statue. Then the inscription was chiseled out and the stone re-used in a later monument, probably a commemorative arch spanning the ancient road which has been traced near the site where the relief was discovered. It was for this arch that the back surface of the stone was carved with figures which, in fact, formed a part of a longer relief the remainder of which is still undiscovered. From this it can be seen that a reading of the inscription might provide a date after which the relief of necessity must have been carved. The relief itself is artistically of great importance since its style is to be associated with that of the famous Cancellaria reliefs discovered in Rome and ranked as an outstanding example of imperial Roman art. These latter reliefs have received much attention and have been dated to the Flavian period–those years when Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian ruled the empire (A.D.69-96).

Within a few years after coming to Philadelphia the Pozzuoli piece was dated by the various characteristics of hair style, clothing forms, and carving to the reign of the emperor Trajan (A.D. 98-117). It was also soon discovered that another fragment of the same monument, joining the Philadelphia piece at the right hand edge, was already on display in the Berlin Museum and had been there since 1830. But this offered no assistance in dating the Philadelphia fragment. Indeed, both items would benefit from a proper reading of the inscription.

Over the years many have tried to discern the lettering so carefully and almost thoroughly eradicated by the hand of the ancient Roman stone mason. Early in this struggle it became quite evident that the wording had to do with an emperor; his titles and the numerical listing of his accomplishments were then to provide a date for the carving of the inscription. The very fact that everything had been erased intentionally gave strong indication that here was a monument belonging to an emperor whose memory had been condemned. Vespasian’s name was found at the head of the inscription and thus led to the conclusion that here may have been a dedication to Domitian, the only member of his family to have lost the senatorial votes for admission to the company of deified emperors. This, then, would be a monument defaced at the order of the senate and not a slab of stone damaged accidentally, then chiseled smooth for re-use.

Indeed, the name of Domitian was finally read under the effacing lines of the vengeful chisel. The problem thus narrowed to one of discerning the Roman numerals coupled with the titles held by Domitian at the time when the stone was originally carved. For this purpose scholars abroad have been compelled to work from photographs or casts of the Philadelphia stone–and this has not simplified matters for them. In publications the photographs have appeared upside-down while the traces of the numerals seem almost indiscernible.

As displayed in Philadelphia the relief was braced to the wall for support, the inscription thus being effectively hidden. But in recent years the program to improve and up-date gallery exhibits has caused the inscription to be moved into the open again and so prompted me to spend many evenings examining the carving by dint of a flashlight in a darkened gallery. The results have been most rewarding and lead to the following reading which leaves little room for doubt.

DIVI VESPASIANI F

DOMITIANO AVG

GERMAN PONT MAX

TRIB POTEST XV IMP XXII

COSXVII CENS PERPET PP

COLONIA FLAVIA AVG

PVTEOLANA

INDVLGENTIA MAXIMI

DIVINIQVE PRINCIPIS

VRBIEIVS ADMOTA

Only the first word of the last line offers serious difficulty yet the visible traces strongly suggest VRBIEIVS. In the past some have tried to read this line as VICTORIS ACCEPTA but the final word is certainly ADMOTA.

In translation this would read, “To the Imperator Caesar Domitian Augustus, son of the deified Vespasian, victor in Germany, Pontifex Maximus, holding the power of Tribune for the fifteenth year, holder of twenty-two military triumphs, Consul for the seventeenth time, Perpetual Censor, Father of the Country, [erected] by the citizens of the Flavian Colony of Puteoli, [for something] moved to the city [?] by the indulgence of the great and divine Princeps.”

In essence this indicates that Domitian conducted or moved something to Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) in return for which the citizens of the town erected a monument with this inscription to show their gratitude. It is very likely that the stone bearing the inscription was actually the front of a base supporting a statue of Domitian. As to the nature of Domitian’s munificence we may only guess. Perhaps the reference is to an extension of the Appian Way which he constructed from Sinuessa along the coast to Cumae and so to Puteoli; this was accomplished in A.D. 95 and would be appropriate as an explanation of the inscription if indeed the inscription were erected about that time. Unfortunately the word ADMOTA bears the implication of moving something bodily from one place to another and may itself rule out any connection with the new road.

The inscription is, of course, composed of the standard Latin abbreviations used in monumental carving; in addition there are accent marks above the letters A, O, and E wehre such a vowel is to be accented. The sculptor also inserted a single long line above each group of numbers. These latter lines are now of great assistance in deciding how many numerals should be read in each group.

Turning to an interpretation of the inscription we find that Domitian is called Germanicus, a title which he received for the successful German campaign of A.D. 83 which he conducted in person. Pontifex Maximus or head of the college of priests at Rome was a position held by Domitian from the first year of his reign until his death.

Museum Object Number: MS4916A

In Republican times the tribunes of the plebeians were, in a sense, public defenders committed to protect the rights and property of the ordinary citizens. Their persons were sacrosanct. When Augustus established the Empire he refused to remove this post completely from the political succession of offices by assuming it himself–=but he did claim that the tribune’s sacrosanctity would henceforth apply to the emperor. Since this protection was inherent in the tribune’s power rather than merely in his title, Augustus announced that he would hold the power of tribune and not the tribuneship itself. From this moment it became the practice of emperors to date the years of their reigns according to the number of times they had held the power of the tribunate, inasmuch as it was renewed each year. Thus our inscription clearly indicates that Domitian had held this power for fourteen full years and was already into the fifteenth year of his reign when the dedication was carved in the marble slab. Earlier attempts to read the number at this point in the stone have produced the Roman numeral V or VI. However, the length of the line above the numerals and the serifs of an X preceding the V show that this is to be read XV. It was on the fourteenth of September, A.D. 81 that Domitian came to the throne and this, in succeeding years was the anniversary of his assumption of the tribunican power. Our Philadelphia inscription must be dated therefore between this anniversary date in 95 and the same date in 96.

In the spring of 93 Domitian had celebrated the conclusion of his campaign against the Suevi and the Sarmatians, the twenty-second victory of his armies abroad; this number was not increased by the time of his death and so appears as XXII in the inscription. Two X’s may be discerned in this number thus invalidating an earlier published reading of XII.

In Republican days, before the revolutions which brought Augustus to power, there had been two men at the head of Roman government–the annually elected consuls. Under the Empire they were replaced in authority by the emperor himself but the position of consul was still retained in the list of public offices. Not always but frequently an emperor would include himself as consul in the consular appointments submitted by him and automatically approved by the Senate. Domitian held seven consulships while his father and his brother were ruling and during his own reign he assumed the consulship on ten occasions, more than is recorded for any preceding emperor. On the first of January, A.D. 95, he became consul for the seventeenth time and thus we find agreement with the date supplied by the number attached to the tribunician power. Unfortunately Domitian did not take the consulship in 96 and this particular title as numbered in the inscription does not allow us to refine our scope of dating. There is no doubt, however, that the seventeenth consulship is here listed and not the seventh as has been published in earlier studies.

Museum Object Number: MS4916A

In 85 Domitian took to himself the title of Perpetual Censor and continued to hold it throughout the remainder of his life. This enabled him to control the composition of the Senate and to enforce rigid laws against immortality among Roman citizens. But it offers us no clue to dating other than that the inscription could not be earlier than 85. Since we have already derived a later date we may only appreciate the fact that Domitian did not think the title incongruous for himself and so enjoyed it to the end, in spit of the fact that any other censor would have taken serious exception to Domitian’s own libertine ways. Of similar inconsequence to us is the title Pater Patriae which he held at least from the year 82.

According to this new reading of the Puteoli inscription there can be no doubt that it was carved after September the fourteenth of A.D. 95. Former endeavors to bring its numerical indications into conformity with the titles held by Domitian in 86 must now be discarded. If the dedication is indeed connected with the highway extension from Sinuessa, purely as imaginative supposition one may guess that it was not prepared until the road had been completed. Since the paving would be laid during good weather, and architects were extremely aware of such a requirement, it may be assumed that it was begun in the spring of 95, as is suggested by ancient texts, and either finished late in the fall or else in the following spring when appropriate weather had returned. In either case the foundation for the base with the inscription would most likely have been constructed in the spring of 95, as is suggested by ancient texts, and either finished late in the fall or else in the following spring when appropriate weather had returned. In either case the foundation for the base with the inscription would most likely have been constructed in the spring of 96, thus bringing the creation of the inscription almost within six months of Domitian’s death.

In surveying the information obtained from this inscription we see that it is a concise sketch of the entire reign of an emperor whom Roman high society and government officials both feared and despised. The accomplishments of a fifteen-year reign and forty-five years of life were recorded here for posterity–then obliterated with violent precision. Just as the citizens of Puteoli honored the living Domitian with the title of “Divine” in their dedication so, within the space of no more than a year did the Roman Senate dishonor him by withdrawing his passport to the celestial realms. Five days after his fifteenth year of tribunician power had expired and he had entered into the sixteenth, Domitian was brutally deprived of his military victories, his tribunician power, his consulships, his priestly titles, his ambiguous role as censor, his life–and his divinity. As one more evidence of this, the fate of too many worldly rulers, the University Museum is privileged to exhibit the inscription and relief from Puteoli.