The 1964 staff of this expedition consisted of Mrs. Carter of the University Museum and David Oates, Director of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, as Directors. Barbara Parker of the London Institute of Archaeology served as epigraphist. David Crownover of the University Museum and Nicholas Kindersley and Julian Reade, Fellows of the British School were all staff members. The expedition was also professionally assisted during portions of the spring by Professor Jorgen Laessoe, University of Copenhagen; David H. French, British School of Archaeology in Ankara; Jeffrey Orchard, Secretary of the British School in Iraq; Nan Shaw and Anne Searight, Fellows of the British School in Iraq. Sayyid Tarip al-Naimi served as the excellent representative of the Directorate General of Antiquities.

Percy Madeira, in his recently published Men in Search of Man, describes in vivid detail the organization of our Museum’s first dig in Mesopotamia and the agonizing difficulties which beset the enterprise. The 1888 Expedition to Nippur was the initial archaeological venture of our institution.

Many of the University of Pennsylvania’s past efforts have been in ancient Sumer, south of modern Baghdad. During the interval between World Wars we had other notable interests in northern Iraq, more specifically in the area near Mosul and east of the Tigris River. Between 1928 and 11931, we joined with the Fogg Museum of Harvard University and the American School of Oriental Research in Baghdad in an expedition to Nuzi (Yorgan Tepe). Under the direction of Professor Ephraim A. Speiser, and of Oriental Research in Baghdad, we dug at the enormous site called Tell Billah (Akkadian, Shibaniba) from 1930 to 1935. Tepe Gawra was excavated intermittently under Dr. Speiser’s direction in the period between 1931 and 1938. The financial burden of this work was also shared with the American Schools of Oriental Research and Dropsie college.

With the exception of recent Danish activities in the region of the Dokan Dam, the University of Pennsylvania has been wholly responsible for our archaeological knowledge of the 4th, 3rd, and 2nd millennia in Northern Iraq. Therefore, when the Directors of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq proposed that we join them in a project in this general area, it seemed eminently appropriate to re-initiate activity in Iraq, and at the same time to continue the tradition of Anglo-American co-operation so admirable demonstrated by Sir Leonard Woolley and his staff in the excavations at Ur.

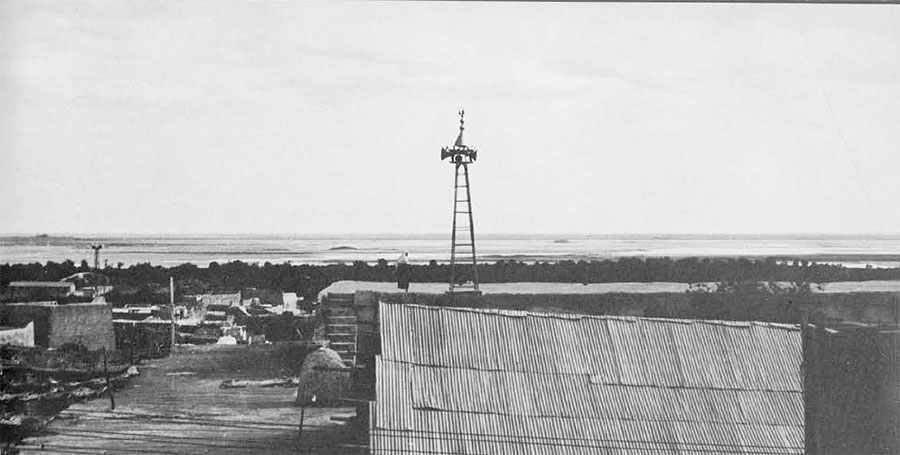

The site selected for the present campaign is to the west of Mosul and the Tigris River. Apart from a mound survey and a few small sondages made by Professor Seton Llyod in the late thirties, this area is virtually unworked by archaeological spades. Tell ‘Afar, a market town of some 30,000 people, lies 65 kilometers west of Mosul; 13 kilometers south of Tell ‘Afar one could look toward Rimah on a clear day and distinguish a hundred a hundred other mounds of varying sizes and shapes in the same plain. The Jebel Sinjar rising occasionally as high as 1,200 meters, fringes the region on the north. Not far south of Rimah the once-fertile plain merges into the Syrian Desert and stretches in a vast waste to the Euphrates and beyond. A settled population, either ancient or modern, could subsist only in a limited area near enough to the Sinjar Hills to the benefit from their rainfall. On the north side of the Jebel Sinjar are other tells which bear witness to the extreme dependency of this area upon climatic factors. The whole of northern Mesopotamia is framed on the large scale by the Taurus Mountains of Turkey, which blend somewhere n the hill country of Kurdistan into the Persian Zagros Mountains, the latter separating modern Iraq and Iran as effectively now as in Hammurabi’s time.

We know much of this area to have been occupied in prehistoric periods. During our Friday holidays and on many twilight evenings, we had an opportunity to investigate some thirty other tells in the Sinjar vicinity. We found, as had Seton Llyod, clear evidence of regional occupation from Neolithic through modern Islamic. This investigation is a matter of combing the surface of the tell and associated outlying features, thereby obtaining representative collections of sherds, flints, seals, and terracottas. After prehistoric times, we still have almost no written information for his part of northern Iraq in the later third millennium. This is the Early Dynastic period in the south and the hey-day of Ur and Nippur. In the north, we identify its passing with a distinctive type of pottery called Ninevite 5, after a ware in the fifth level of ancient Nineveh, located at the outskirts of modern Mosul. The town of Ashur, later to become the capital of the great Assyrian Empire, had been founded, and was to some extent in contact with other urban centers, but Assyrian influence did not extend much beyond the confines of the city limits.

We have no direct references to this area in Akkadian times, although Sargon the Great claims an empire extending to the Mediterranean Sea. His grandson Naram-Sin built a fortified palace at Tell Brak not far away in Syria. The area in general is called Subartu by the Akkadians, who give the impression that the population consists largely of nomadic tribes. At any rate, there is ample pottery evidence for occupation here in the mid-second millennium. During the Neo-Sumerian revival, Ashur fell into the control of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and was ruled by a governor. The status of the Snijar at this time is not clear. Presumable West Semitic Amorites were moving east from their nomadic encampments in Syria. In their traditional king list recorded by the Assyrians around 2000 B.C., their predecessors are listed as “kings who lived in tents.”

At at ime around 1825 B.C., a strong king emerged from this Amorite background and masterfully seized control of northern Mesopotamia. Shamshi-Adad I expanded the Old Assyrian Empire to the Khabur River on the west and to the Euphrates on the south, Chagar Bazar to the north and the Zagros foothills on the east. The diplomatic correspondence of the Mari archives reveals him as an astute politician, an able administrator, and a competent military chief of staff, who was constantly alert to the political advantages which might be derived from frequent pilgrimages to all of the distant ceremonial centers for the performance of sacrifices. Some ten years before Shamashi Adad’s death, there arose in southern Mesopotamia a worthy challenge to this power, in the person of Hammurabi of Babylon. He too, was descended from Amorite backgrounds and thus a West Semitic dynasty flourished also in Babylonia.

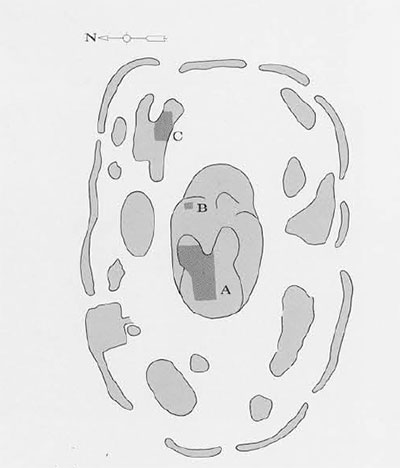

In this political climate, and in the described geographical setting, around 1800 B.C. the foundations of Tell al-Rimah were put down into the Sinjar plain. A mud-brick city wall in the rough form of a rounded rectangle was constructed to protect the inhabitants and buildings contained within. In the vague hope of obtaining some information about the founding of the city, we sank three deep sondages in the “Palace” mound; one of these reached virgin soil at a depth of more than eight meters. Just over the virgin soil, lodged near the underpinnings of a massive mud-brick wall, were the remaining fragments of four tablets in the Old Babylonian script of Shamshi-Adad’s time. from what can be read of them, it seems that they are lists of rations probably of fruit for a number of people bearing Amorite and Hurrian names.

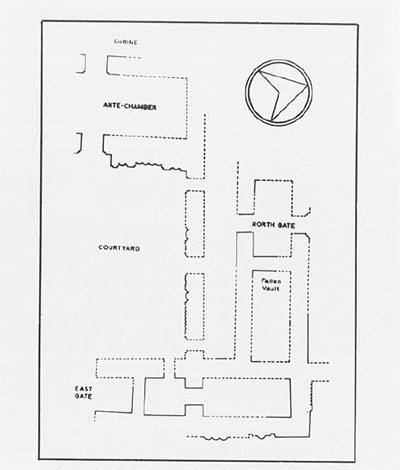

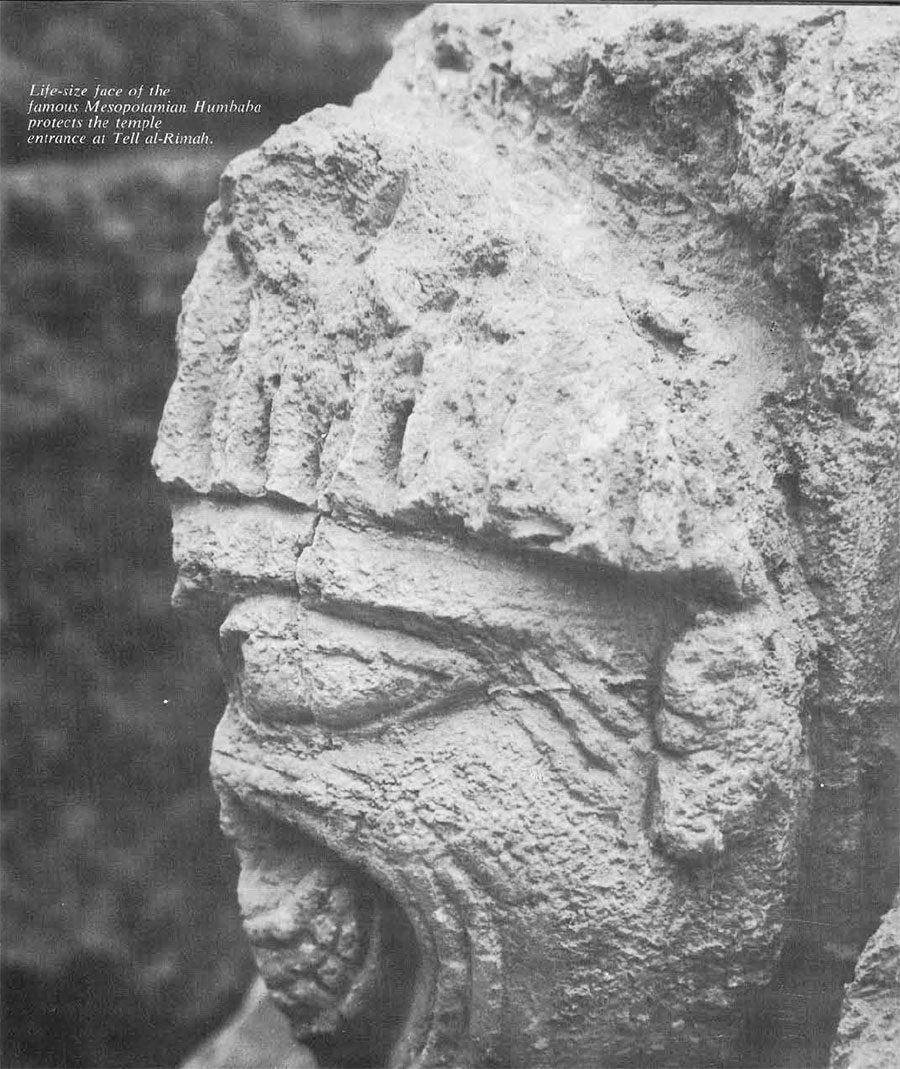

The center of the city and its chief feature is the temple tell. The back of the structure drops vertically to the plain, but the entrance on the east is stepped up apparently in three stages: the lowest fans out broadly to the front and sides. A ramp or steps led to the second stage, which consisted of an axial and symmetrical courtyard system with rooms balanced on either side. The uppermost stage was the shrine itself. All of the exterior and interior court facades were decorated with engaged half-columns and rebated niches with black paint and bitumen dados. The plan, as recovered, is strongly reminiscent of Shamshi-Adad’s temple to the goddess Ishtar at Ashur. It is more than likely that Tell al-Rimah was a religious center of importance in which Shamshi-Adad may have conducted annual ceremonies. We have not yet exposed the plan of the Old Assyrian temple, but the later rebuilding and renovations suggest that the most monumental and elegant phase will be the earliest and original temple. Certain pieces of sculpture which must date to the Old Babylonian period were re-used in upper levels of the temple. Among these was the remaining half of a life-size grotesque stone mask, carved on the end of a rectangular stone block, obviously intended as a functioning architectural member. The style adheres to a protective demon form known from earlier terracottas in southern Mesopotamia. This particular type is usually called Humbaba, after the great fearsome dragon of the Gilgamesh epic. Also we recovered a small limestone bust of a straggly-bearded male. Clay sealings of the Old Babylonian period reflect contemporary seal designs.

In the palace we know very little as yet of the original period, but the walls at that level are massive and well-constructed of large flat mud-bricks. A sophisticated drainage system and storage magazines were probably established in the early phase. Clues to the nature of the population are furnished by the tablets from the palace. Amorite (West Semitic) names were common in the Shamashi-Adad royal dynasty; Hurrian names at this time are identified across the whole northern arc from the Syrian coast to the borders of Iran.

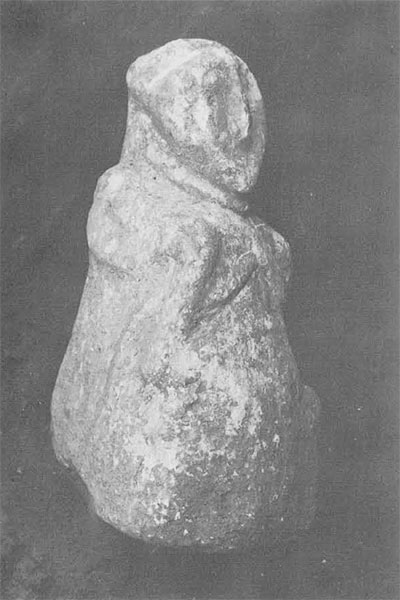

The next period somewhat illuminated by our 964 discoveries is that of about 1500 B.C. when the Mitannian kingdom was amassing power in the west. Tell al-Rimah is situated in such a position that it may have been a sort of political no-man’s land, as the fortunes of the Assyrians and Mitanni to either side waxed and waned. Our series of cylinder seals from these strata are predominantly of Mitannian and Syrian style. In the statuary category, our comparative material also points in this direction. At this time the palace incorporated a shrine complex; a crudely fashioned stone female statuette was preserved in situ on a bench in the white-plastered shrine. A somewhat squatter, but closely related male counterpart was brought to light on the temple mound at the entrance to the inner chamber. Both belong stylistically with contemporaneous figurines from North Syrian sites.

An incredible number of objects of glass, frit, and glazed pottery were discovered in caches in rooms surrounding the temple courtyard. Among these were frit lidded cosmetic capsules, bearing designs known from the glyptic repertories of both Syria and Assyria. There were also mosaic glass vessels, theriomorphic polychrome vases, glazed and frit beads, amulets, and colorful rosettes. The accompanying article by David Crownover discusses the frit material in detail. Suffice it to say here that the majority of the frit and glazed amulet and bead types were paralleled in the Nuzi finds of exactly the same period, particularly the miniature flies, frogs, Ishtars, and lions. At Nuzi, the glass vessels were exclusively from the palace, indicating their probably use by the inhabitants, whereas the Rimah vessels were found only in the temple.

One of the most artistically superb objects found this season is a finely enunciated female mask in frit bearing traces of a pale green glaze. It is markedly similar to several found by the French Mission in Assyrian graves at Mari. A predictable number of objects in terracotta and pottery were scattered about the temple courtyard, including a medium-sized pig vase; the type is known from Nuzi, where they were thought to represent lions. The feet are pierced for wheel attachments; a quantity of loose wheels in both pottery and stone of all sizes emerged from the temple debris. These testify to the presence of numerous quarter- to half-life size animals-on-wheels, probably used as temple furniture in Mesopotamian ritual scenes. Among several anthropomorphic terracottas was a little robed man with bitumen beard and a whistle arm. Philadelphia is fortunate in receiving as part of its share a fine limestone jar lid decorated with a couchant feline in the round, his forepaws engagingly crossed under his chin. There were, of course, necklaces of gaily variegated shells, and large decorative pins of bronze and bone.

In the palace of 1500 B.C. the previously mentioned plastered shrine and the surrounding complex of barrel vaults and courtyards are obviously of importance, as are the well-articulated walls and drains of the earlier phase of the same general cultural period. We found in the rubble of this level a dozen or so bitumen coated wall nails, gigantic in size. These are recognized at both contemporary and later sites; they were used in public buildings as decorative elements, planted in the mud-brick walls at shoulder height, forming a horizontal band inside the room. However, at Nuzi and Ashur they are smaller and glazed. Quite a few “eyes” both in frit and stone were discovered on the temple mound; they may have been used in the same way, or perhaps the smaller ones as embellishments for furniture.

The temple shows unmistakable signs of burning and deterioration in the approximately three hundred years between Shamshi-Adad’s time and 1500 B.C. However in the mid-millennium it was cleaned, the facade repaired, cobbled paths rerouted, and black dados applied all way round the interior. The great stone Humbaba was reused in a curious position at the entrance to the temple inner court. A few scattered tablets list a number of Hurrian men and their wives involved in legal disputes. The temple court of the second stage is considerably less prosperous than previously. Some of the surrounding rooms formerly occupied by priests or used for cultic enactments, seem to have been actually dwellings.

Others, naturally, continued to function as temple storage; great masses of frit and glass jewellery came from a single room. It is equally clear from this that the occupation by a Hurrian-speaking population came to a rather abrupt end. One does not find collections of valuable objects abandoned on floors when a city is methodically and peacefully deserted. As archaeologists we are delighted with these disasters or disruptions in occupation, as our chances of recovering exciting material are many times increased.

One of the most fascinating aspects of continued work at Tell al-Rimah is that in a few more seasons tablets and other inscribed material should help us to fill these historical lacunae of the second millennium.

After the mid-millennium desertion, both temple and palace mounds were thoroughly re-occupied. The pottery, in fact, suggests that the desertion was very short-lived, as the ceramic sequence, based on what we know from Tell Billah and other sites is nearly continuous.

In the palace, it is likely that most of the rooms were rel-aligned and made smaller. The mud-bricks themselves were smaller, and of a reddish color instead of the earlier grey tone. It is quite possible that the plastered shrine continued in use; in the same complex, one of the magazines was surmounted by a pitched brick vault which is believed to be the earliest use of the architectural form above ground. The temple mound appears to have lost its religious function and become totally residential. In one of the rooms near the summit at a mete’;s depth below the surface, we discovered a jar containing several dozen tablets. These were jammed against one another in such a way that they could not be extracted even when the jar was broken away. However, almost constant diurnal and nocturnal efforts by the more patient among us succeeded in extricating the better part of thirty records of a Middle Assyrian merchant. The tablets were precisely dated by the limmu years mentioned to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser I (ca. 1300 B.C.) and in addition to the field rentals and legal contracts, dealt with the commodities of grain, tin, and copper. This was of immense interest since David Oates had long suspected that Tell al-Rimah was situated in a most tempting location for commercial caravans linking Ashur, via one of three possible passes in the Jebel Sinjar, to Anatolia beyond. The mention of copper and tin is exactly what one would hope for in this connection. This was a period of Assyrian strength and Rimah was undoubtedly in that sphere of influence.

Later periods at Rimah are poorly represented and the Late Assyrian (9th to 7th century) habitations at the base of the temple mound are scarcely worthy of our notice.

At the conclusion of ten weeks digging we covered some of the more unusual mud-brick architectural features until next season. We nurture the latent hope that in our lifetime someone will invent an adaptable and inexpensive means of preservation for these remarkable examples of ancient architecture. Our 1965 campaign should lay bare to some extent portions of the Old Assyrian palace, and perhaps that period of the temple as well, including the innermost shrine.

We cleaned and packed our antiquities and delivered them to the superb new Baghdad Museum. A most reasonable and generous division was effected between the Expedition and the Directorate General of Antiquities of Iraq in the persons of Dr. Feisal el-Wailly, Director General; Sayyid Fuad Safar, Director of Excavations; and Sayyid Farach Basmaji, Baghdad Museum Director. Immediately afterwards our Museum divided with the British School of Archaeology in Iraq. Our lot is expected momentarily in Philadelphia.