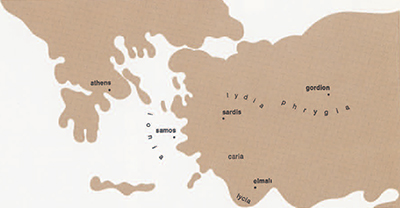

The excavations and study by the late Erich F. Schmidt at Persepolis and by Machteld J. Mellink at Elmali in western Turkey have had an unexpected side benefit in that they have provided the evidence to help clear up a puzzling and even embarrassing problem in Greek antiquity. Thus, findings at a royal Persian building, the tombs of the Persian kings, and the tomb chambers of the Western Anatolian rich allow us to come a little closer to the realities of Greek life in the late sixth and the early fifth centuries B.C.

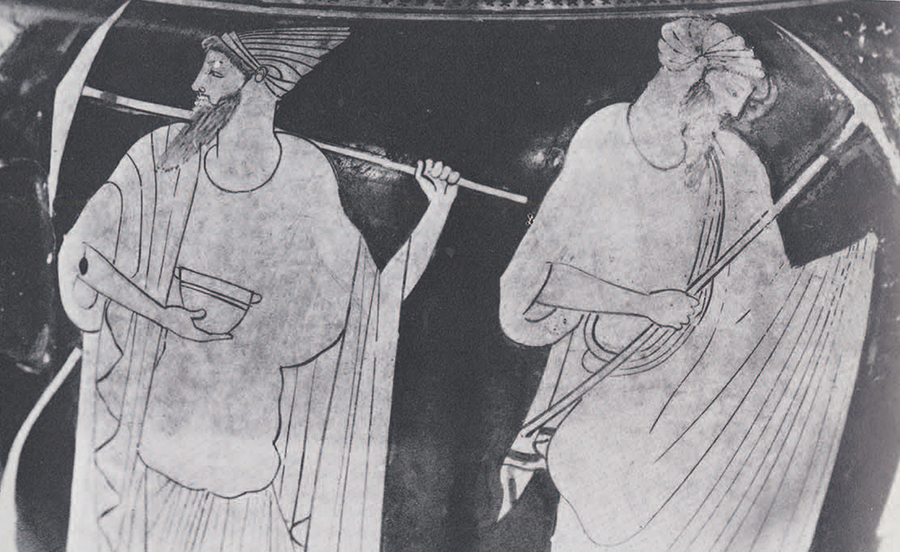

About thirty vases painted in Athens at that time show the sorts of bearded male figures illustrated here on an Attic krater and a stamnos. The men are dressed in a sleeved robe (chiton) that reaches down to the feet; the densely packed lines of the material indicate that it is linen. Above the chiton and thrown over one shoulder comes a loose, heavier garment (himation), presumably of wool. Wrapped around the head is a cloth forming the type of headdress known as a sakkos. The men carry parasols in some representations. and in two instances they clearly have on earrings (as in this krater).

About thirty vases painted in Athens at that time show the sorts of bearded male figures illustrated here on an Attic krater and a stamnos. The men are dressed in a sleeved robe (chiton) that reaches down to the feet; the densely packed lines of the material indicate that it is linen. Above the chiton and thrown over one shoulder comes a loose, heavier garment (himation), presumably of wool. Wrapped around the head is a cloth forming the type of headdress known as a sakkos. The men carry parasols in some representations. and in two instances they clearly have on earrings (as in this krater).

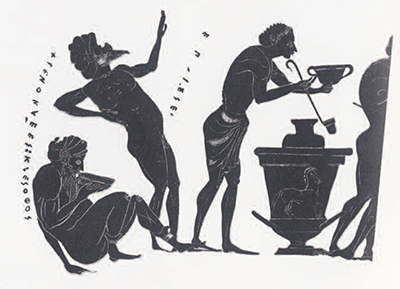

The scenes are lively. Often the men dance with wine cups near to hand, and quite frequently one man accompanies them on a lyre; once a name is written by him: Anakreon. The name is meaningful, since an Anakreon was a poet associated with the tyrant Polykrates on the Ionian, or East Greek, island of Samos up to ca. 523 B.C. and who later, in a time of troubles that brought Samos into the Persian Empire, found refuge in Athens. Twice in the representations the presence of couches and men reclining on them indicates that the setting is that core institution of Greek culture, the drinking and dinner party known as the symposion.

The usual interpretation, which has been expounded most fully by the late Sir John Beazley, finds the scenes at least mildly scandalous and views the men as dressed in women’s clothing. For Beazley and others, the combination of long chiton with himation would have been female dress in Greece by the time of the vase paintings. though standard male apparel in earlier generations. The sakkos is seen as having always been characteristic of women, and the parasol and earrings as even more emphatically feminine.

Museum Object Number: L-64-40

It was Beazley who, accepting reasonably enough an equation of the Anakreon on the one vase with the known poet, first urged that all the lyre players be identified as Anakreon and that the scenes be taken as gatherings of him and his friends; Anakreon’s circle would thus consist, to put it bluntly, of frolicking transvestites. What then is seen as strange is the fact that Anakreon himself in some of his surviving lines mentioned many of the very articles of dress depicted in the vase paintings and that in these lines, as usually understood, Anakreon categorized the articles and a man making use of them as effeminate. The poem is an attack on an Artemon, a personal enemy probably on Samos.

“There was a time when he wore a berberion —that wasplike covering [sakkos?]—wooden pegs j?] in his ears, and a worn cowhide about his body…. Now he rides in a chariot, wears golden earrings .. and carries an ivory parasol, like a woman.”

The supposition, by this line of reasoning, has to be that the pot Anakreon is calling the kettle Artemon black.

Even without the evidence from Elmali and Persepolis, the orthodox interpretations summarized above would be none too convincing. Most generally, transvestite dinner parties, even among a restricted clique, are hard to imagine in the context of the intensely male Greek society of the time. They might be possible as the subject of a slanderous joke, but as an actuality they would jar badly with all else that we can understand about that culture.

More specifically, the clothing when studied closely doesn’t seem particularly female. It is true that by the fifth century the standard Greek men’s clothing was coming to be a himation alone or a short chiton and its variants alone. Thus, Herodotes writing in about the third quarter of the fifth century could find it worth mentioning that among the Lydians (non-Greek Anatolians to the east of the Aegean) men wore a chiton below the himation (I. 155), and he did find this a sign of softness. though he didn’t necessarily take it as a copying of female ways. Nonetheless, in Attic vase paintings of the first half of the century the combination of long chiton and himation is still quite commonly found on representations of respectable and vigorous enough looking men.

The sakkos, too, can hardly have been an item that would suggest a female appearance, since men can wear it and nothing else at a symposion.

Upon examination, the Anakreon passage itself turns out to be not very conclusive. There is some ambiguity as to just what is being considered womanish in Artemon’s life-style. It might be that the judgment is so narrow as to be directed only toward the parasol; more probably, though, it refers generally to the extreme luxuries in which the man indulged. In any case it would not be earrings per se that Anakreon would be considering effeminate but at most those of the rich metal gold, since Artemon’s former wooden earrings escape such a rebuke and get treated instead with disdain for their meanness. In the same vein, it is even possible that the parasol, the one item unquestionably considered effeminate, is criticized for its luxurious material. And the sakkos, if that is what it was, is definitely not included in the womanizing category.

Nonetheless, it has to be admitted that even though the long chiton and the himation seem innocent enough in the context of Attic vase painting of the time, that the sakkos isolated does too, and that Anakreon’s condemnation of parasol and earring is not as sweeping and unambiguous as usually supposed; still the representations on Attic pottery of men with all these items together is strange. While the interpretation of the figures as transvestites is dubious, we are left with the puzzle of who they are meant to be.

Help comes from Persepolis and from the most majestic of contexts. In the early fifth century Apadana reliefs depicting subject delegations of the Persian Empire bearing gifts to the king, one of the groups is nearly identical in its dress to the figures on the Attic vases: the men wear the sakkos, the himation, and the long chiton of crinkly linen. They lack the earrings and parasol, but so do in fact the vase figures often enough; also, the Persepolis delegates differ by having a long braid that comes down behind one ear. Members of another delegation are also dressed quite like the key group but lack both sakkos and braid.

Clearly, the figures on the Apadana friezes should provide some illumination for those on the Attic vases, but the precise identity of the sculptured figures themselves is not immediately apparent. For them too, an interpretation has to be arrived at indirectly.

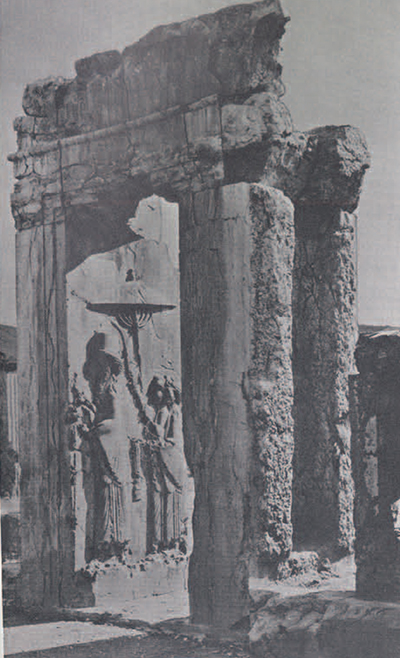

The peoples of the Persian empire were also depicted in certain other sets of sculpture, of which the most relevant here are the facade reliefs on the tombs of the Achaemenian kings at Persepolis and nearby Naqsh-i Rustam. On these, the figure types, conceived of as supporting a platform on which the king stands, are always in the same order and are nearly identically represented from one tomb to the next. Most important, on two of these tombs, that of Darius I (reigned 522-486) and perhaps that of Artaxerxes II (reigned 404-359), each of the figures is carefully labeled with the name of the national group for which it stands.

Two of these labeled figure types are crucial: the Lydian and the Ionian (the latter representing the East Greeks of the Asia Minor Aegean coast and the offshore islands). On the whole, the two peoples are represented in just the same manner, as wearing a short, knee-length chiton and a short cloak (chlamys) secured at one shoulder. Both articles of clothing are represented frequently in Greek art, and it is gratifying that a painting in a fifth-century tomb uncovered by Miss Mellink near Elmali (in the ancient region of Lycia, to the south of Lydia) confirms that the garments were also known and worn in non-Greek Western Anatolia. The Lydian figure differs from the Ionian by once having puttees wrapped about the lower legs (again reflected in the Elmali tomb painting) and, most strikingly, by having in at least one representation a braid coming down behind the ear, in just the manner of the braid noted on the Apadana delegation. It should be noted that of the thirty peoples on the tomb reliefs, only the Lydian has this trait.

Having fairly close correspondences to the Lydian and the Ionian figures are two others on the tomb facades, one standing for another Greek group, probably the North Aegean Greeks (the figure differs by wearing a broad hat), and the other representing the Carians, again a Western Anatolian people (the difference here, and it is slight, lies in the cloak).

From the tomb reliefs with their secure identifications we can return with some confidence to the Apadana sculpture. For the group of sakkos wearers, Schmidt and others have rightly argued that the tell-tale braid ought to identify them as Lydians, since on the Apadana, too, only they have such a hair style. The delegation which so closely resembles the Lydians ought to be the Ionians, just as the Ionian type is so much like the Lydian in the tomb art; perhaps, however, it cannot altogether be excluded that the second group might be the North Aegean Greeks or the Carians, since those peoples would not otherwise be represented in the Apadana friezes. That the short chiton and cloak of the tomb reliefs have become the long chiton and himation is no surprise and ought not to put the identifications in doubt; other peoples which seem to be in both contexts also expose less of their flesh on the Apadana reliefs, perhaps because of the formal occasion celebrated there. Thus, an Indian people, bare-chested on the tombs, is cloaked in the tribute procession, and the legs of the Assyrians are bare on the tombs, covered on the royal building.

The combination of long chiton, himation, and sakkos which the party goers on the Attic vases wear is, then, precisely the dress of the Lydians of Western Anatolia, as shown on the Apadana reliefs, and with the sakkos omitted it is apparently that of the Ionian Greeks as well. The parasol and earrings of some of the revellers, absent on the two Apadana groups, also have about them a suggestion of some people or culture eastward across the Aegean from Athens. As we have seen, Anakreon in the second half of the sixth century associated both with at least one male, probably on Samos, just off the Asia Minor coast. By the late fifth century to judge from an anecdote in Xenophon (Anabasis, III, 1, 31), earrings must have been given up by the East Greek men but would still have remained current among non-Greek males of the Anatolian mainland: in the army assembled by Cyrus the Younger a soldier trying to pass as Greek was exposed as a Lydian because of his pierced ears. The Elmali paintings, too, establish both the parasol and the earrings as thoroughly at home in Anatolia in the late sixth and early fifth centuries; in one of the painted tombs a parasol shades a passenger on a ship, and in the other a large earring dangles from the ear of a reclining diner (he is also dressed, it might be noted, in long chiton and himation), In fact, throughout the ancient Orient, well beyond the Aegean fringe and western mainland of Anatolia, parasols and earrings must have been unquestioned male accessories. At Persepolis itself, one of the recurrent sculptural themes is the Great King’s walking below a parasol, and on the tomb reliefs both the king and the god Ahura Mazda have earrings.

Elmali, ca. 475 B.C.

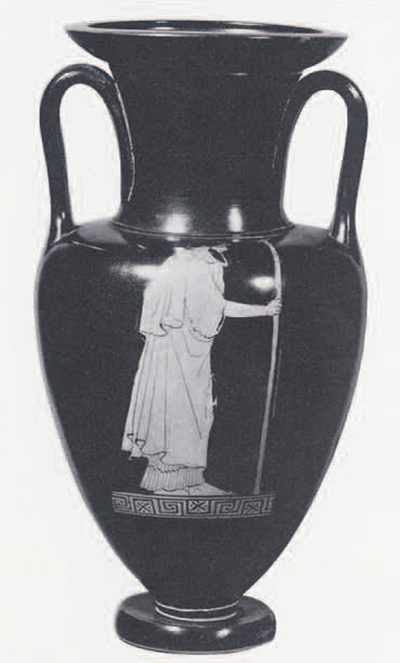

What is more, not only can we see that the figures in the vase paintings have just the ordinary trappings of men in the Anatolian area or still farther east, but at least some Attic vase painters would have understood the figures and their dress that way, too. The evidence comes in depictions of kings of Asia Minor on Attic fifth-century pottery. King Kroisos of Lydia is once shown seated on his legendary pyre and dressed in a long chiton and himation. but similarly dressed, of course, are many apparently Athenian figures of the time. More decisive are two representations of King Midas of Phrygia, who in addition to the chiton and himation is given a headdress very like the sakkos of the revellers and of the Lydians of the Apadana reliefs. In one instance the sakkos is oddly elaborated with the flaps of a Persian or “Phrygian” cap, and in the other it is abbreviated to a snood.

Even granted, however, that the Attic revellers are decked out in the manner of Easterners and that the vase painters and presumably their customers are likely to have understood them that way, still some of the puzzle remains of exactly who the figures are. A number of answers seem possible, with perhaps none absolutely conclusive.

If in some unlikely situation the Apadana sculptors could have been shown the vase paintings, it seems likely that they, judging by the sakkos, would have declared the figures to be Lydians. Herodotos, later, taking into consideration the combination of chiton and himation might have been inclined to agree; and later still, Xenophon surely would have assented. on the basis of the earrings. It is perfectly possible that such is the true interpretation, that the figures are by and large meant to be Lydians, who somehow came into the real or artistic vision of the Attic craftsmen.

However, it cannot be shunted aside that one of the figures is labelled Anakreon, the non-Lydian, East Greek poet, and it cannot be ignored either that so many of those features that taken together seem Lydian are attested by Anakreon for a person probably on Greek Samos. The Beazley hypothesis that all the scenes represent Anakreon and his friends might still be sound. It would be quite understandable that those in the flamboyant circle of the tyrant Polykrates on Samos might come closer in their fashions to the Lydians than did the bulk of the East Greeks, and it would be plausible, too, that Anakreon, perhaps with other refugees from Samos. might continue to dress in much the same manner later in Athens. What the vase paintings could have been recording then is the impression that an expatriate Samian circle was making on Athenian society.

Still another possibility suggests itself. It might be that the figures are generally meant to be Athenians, but Athenians of a special set who were aping Eastern ways and dress, whether they were taking their cues from Anakreon, Lydians they had seen in Athens, or still other inspirations.

Whatever the exact explanation, the Anatolians, local Anatolianizers, or East Greeks weren’t really unique at Athenian parties. Other vase paintings of the time show mixed with guests in ordinary enough dress, drinkers wearing the tiara cap usually associated with Iranians or Scythians. It appears that foreigners or local enthusiasts for their dress might have been commonplace at gatherings of the period. East and West clearly met, and even at this time of military tension, encounters and exchanges weren’t limited to the battlefield.

- King Kroisos, sitting on pyre and pouring out libation. Attic amphora, ca. 490 B.C.

- Diner to left at symposion has Persian of Scythian headdress. Other figures are dressed inn manner of ordinary Greeks. Attic kyliix, ca. 490 B.C.

- King Midas’ donkey ears protrude from his sakkos, Attic stamnos, ca. 440 B.C.

- King-Midas with skimpier headdress but same donkey ears. Interior of Attic kylix, ca. 440 B.C.