Indigenous cultures around the world retain knowledge of a diversity of plants in their environments, including plants used for medicinal purposes. In recent decades, media attention has focused on tropical rain forests, whee local healers have for centuries made use of the biodiverse resources to develop rich pharmacopoeia. Less attention has been paid to semiarid and arid zones such as the savannahs of Africa, where pastoralists like the Maasai rely on an intimate knowledge of their environment for survival. In these harsh environments conservation of plant diversity is critical in maintaining a fragile balance in the competition between the herds of the pastoralists and the local wildlife for the limited available grazing.

Despite the lack of media attention, a great number of scholars have been attracted to East Africa and arid-lands research. Most focus on pastoral areas, pursuing a variety of ethnographic, ethnomedical, ethnobotanic, ecological, and ethnoveterinary studies. Building on this body of scholarship, in 1990, I and a team from the National Museums of Kenya (Nairobi) began an investigation of livestock and range management as practiced by the Maasai pastoralists in Kajiado District, Kenya. Explicitly ethnoarchaeological, our study of Maasai behavior in the present was designed provide insights into subsistence practices in the prehistoric past. We selected six Maasai settlements (bomos) of varying sizes in different areas of Kajiado District, each area with slightly different vegetation cover, access to grazing and water, and rainfall. Elders and their relatives from all six bomas agreed to work with us. and over the next 10 years made us part of their families and instructed us in how to be “real Masai.”

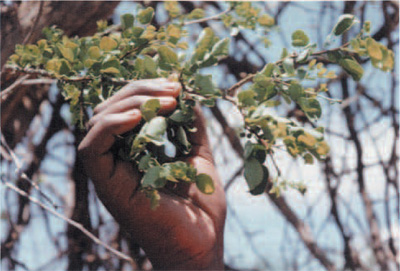

As part of our study, we recorded the prevalence and extent of livestock disease, the main cause of mortality in Maasai herds. Elders described symptoms and discussed recommended treatments and prognosis for recovery. Western and traditional medicines are used side-by-side, but the high cost of Western treatments often precludes their use. For some diseases, traditional plant-derived medicines are actually preferred. In September 1995, we began collection and documentation of the use of botanicals, with a particular emphasis on those used in traditional medical and veterinary practice. Kajiado District has limited and unpredictable rainfall. Ideally it has a hi-annual rainfall pattern of “long rains” from March through May and “short rains” in October or November. We wanted to collect specimens in all seasons in order to record the availability of medicinal plants at different times of the year. September is towards the end of a dry season and just before the “short rains.” Subsequent collections were made in December after the “short rains,” when the combination of recent rain and summer heat promoted rapid growth on the range; in the hot dry season in January, when vegetation was sparse; and towards the end of the “long rains” in May and June, when grasses vital to herd survival were burgeoning.

Although our original focus was on traditional veterinary practice, it became obvious that many plant-derived medicines are used to treat people also. Medicines derived from trees and shrubs are used in the treatment or prevention of a wide range of diseases and include remedies or prophylactics for malaria. sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, diarrheal disorders, parasitic diseases, prostate problems, arthritis, and respiratory disorders. Particular attention is given to women’s health, especially during pregnancy and childbirth.

In addition, herbs, bark, and roots are boiled in soups and ingested to improve digestion and cleanse the blood. Of the 100 plus species that we collected, approximately 30 percent are for remedies associated with stomach problems; they are used for severe gastrointestinal afflictions or added to soups and teas as tonics or to aid digestion. Some, as Timothy Johns suggests (in Etkin 1994:55), are taken as protection against intestinal parasites. Probably the best-known Maasai food additive is derived from an infusion of the bark of Olkiloriti (Acocio nilotica), a stimulant used by Maasai warriors as a digestive aid (Beentje 1994:262) during ceremonies where large quantities of meat are consumed. It is also one of many digestives added to stews to ward off stomach upsets (Spencer 1988:258, 268, n. I).

The next phase of our research—analysis of a selection of plant-derived digestives or food additives—will help us understand the mechanism of therapeutic delivery and may pinpoint species for further research into new and effective treatments for conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or other gastrointestinal disorders.

Apart from this possible application to modern medical research, how is Maasai medicinal and culinary practice relevant to our understanding of human behavior in the past? As self-confessed “non-cultivators,” our Maasai families consume a high proportion of animal protein (meat, milk, and blood) and relatively few plant proteins; moreover, quantity and quality of animal protein is highly season dependent. Consumption of high-fat animal protein in one season may be followed by many months of limited low-fat protein, bringing some families to near starvation. Understanding what role these digestives play in the seasonal delivery of adequate nutrition to Maasai today may provide useful analogs for interpreting human strategies for survival in similarly fluctuating environments in the past.

Kathleen Ryan Research Specialist,

Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology