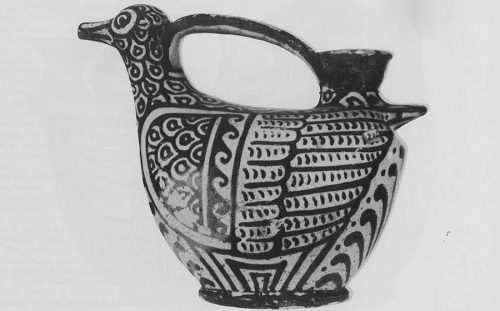

- Etruscan duck-askos of the Clusium Group, with a winged female divinity carrying a long fillet. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. no H 100. Length, 19.5 cm

- Duck askos of the Clusium Group, with a female profile head. Florence, Museo Archeologico, inv. no. 4231.Height, 10.8 cm.

- Etruscan ‘plain’ duck-askos. San Simeon California, Hearst Castle, inv. no. HSHM 5667.

- Bird-askos from Volterra; note the cylindrical bill. Volterra, Museo Etrusco Guarnacci, inv. no. 69. Max. length 31 cm., max. height 20 cm.

- Type A.I bird-askos. Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. no. h 102. Max. length 16.5 cm., max. height 13.5 cm.

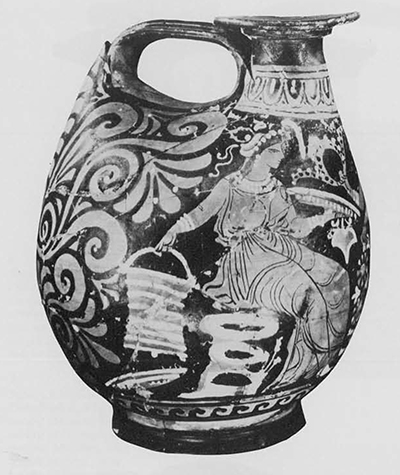

-

Type A.2 bird-askos, Philadelphia, The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania,

Museum Object Number: L. 64. 516. Max. length 18.9 cm., max. height 12.4 cm.

-

Type A.2 bird-askos. Philadelphia, The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

Museum Object Number: MS 1596 , Max. length 24.2 cm., max. height 19.1 cm.

Vases in the form of animals or birds (askoi; askos, singular) have a remarkably long history in Western and Far Eastern art. In ancient Greece, decorated vases shaped as birds were produced as early as the Geometric period (9th-8th century B.C.), and in Italy during the Iron Age (10th-8th century B.C.) there are equally interesting examples of Villanovan fabrication. Much later, during the second half of the 4th century B.C., vases fashioned and decorated as ducks (duck-askoi’} enjoyed a special popularity in Etruria. In the latter part of this period, the duck-askos began to change drastically in its general shape and decoration, even though it maintained its primary functional design and exclusive use.

Duck Askoi

At the beginning of the sequence of Etruscan duck-askoi and their derivatives, the ‘bird-askoi,’ stand examples (Figs. 1, 2 and 3) believed to have been created at the north Etruscan site of present-day Chiusi, ancient Clusium. Within the broad spectrum of Etruscan red-figured vase painting, they are assigned to the ‘Clusium Group.’ These handsome vases are characterized by a full tapering body supported by a ring base which imparts a `swimming’ or ‘floating’ aspect to the ducks; a gracefully curved neck with a head that displays a well-rounded eye in relief; and a broad bill pierced by a small hole. From the duck’s back and set somewhat back from the tip of the tail, there rises a vertical spout with flaring rim. An arched strap handle joins this vertical filling spout to the duck-head pouring spout. To judge by the compact form of the vase and the small aperture at the bill for emission of its contents, such Etruscan duck-askoi must have served as perfume vases with which to dispense the finest of scented oils.

In addition to a richly embellished pattern of stylized wing and body feathers, the painted decoration at each side of these duck-askoi of the Clusium Group frequently shows a Lasa, a winged female divinity and companion of Turan (Aphrodite), who generally carries an alabastron (perfume vase) and its dipstick, or a long fillet (Fig. 1); or, more rarely, the same theme in appliqué; or a profile head— more often female than male (Fig. 2). Some duck askoi bear no figural theme nor profile head.

Bird Askoi

A possible link between the plain duck-askoi of the Clusium Group, the imitations made elsewhere in Etruria, and the late bird-askoi may be represented by an exceptional and highly ornate bird-askos discovered at Volterra and presently in the Museo Etruseo Guarnacci (Fig. 4). Although at first glance the Volterra vase may seem to possess the same rich overall plumage of the Clusium Group askoi— perhaps partly due to the abundant use of added white paint—closer observation discloses a vastly different decorative scheme. The thick upright neck, but more significantly the bird’s head with its trumpet-like bill and large pouring hole at its end, set it conspicuously apart from any of its antecedents of the Clusium Group. In sharp contrast to the graceful, tapering body and tail of the ducks in the Clusium Group, the upper back of the Volterra askos is horizontal and broad, its tail spatula-shaped and slightly uptilted. More than any other feature it is the change in the bill (or beak), from the truly duck-bill of the Clusium Group askoi to a cylindrical bill, that helps classify the Volterra askos and subsequent examples as bird-askoi rather than duck-askoi.

In my early study of late bird-askoi initially regarded as late duck-askoi —I noted that, although the askoi were essentially alike, they could be readily divided into two basic types which were arbitrarily designated ‘Type A and ‘Type 13: Both types are of similar size (height ca. 16 cm., length ca. 20 cm.) and are painted with a considerable variety of details. The chief criterion which distinguishes Type A from Type B askoi is found in the proportion of height to length, first observed and described as “deep” by J. D. Beazley and as such applied to vases I have classified as Type A (Figs. 5, 6 and 7), However, a number of conspicuously deeper bird-askoi unknown to Beazley have come to my attention, which because of their shape and decorative details have prompted my designation Type B (Figs. 8, 9).

Bird-askoi of Type A are noticeably deeper and more ample in the form of their body than is evident for the Volterra askos. At the present stage of my investigation, the basic type can be subdivided into Types A.1 and A.2 on the evidence of their more varied decoration. In general, the bird-askoi of ‘Type Ad (Fig. 5) display tear-shaped feathers which have lost the angularity exhibited by the feathers on the Volterra askos in preference for a rounded and sinuous version. In sharp contrast to the blacked-out lower portion on the Volterra vase, the corresponding area on Type A.1 askoi receives a continuation of the overall decorative pattern, and the area below the tail is `enhanced’ with an upright palmette executed in silhouette or red-figure.

The two examples of Etruscan bird-askoi in The University Museum (UM), University of Pennsylvania, shown here (Figs. 6, 7) serve as good examples of Type A.2 bird askoi. It can be seen that the first of the UM bird-askoi (Fig. 6) possesses a large eye created by a painted circle and central dot, and the tear-shaped feathers have all but disappeared, with the ‘feathered’ head and neck now a series of dots or vertical lines. Of paramount importance, the two UM bird-askoi show their vertical filling spouts—still with flaring rim —set far to the rear, i.e., now located directly above and in line with the vertical plane of the bird’s backside where the tail ‘feathers’ have dwindled to a mere knoblike projection. Of very special significance, the second UM bird-askos (Fig. 7) can be regarded at present as ‘transitional,’ for it well illustrates the deepening of the body so characteristic of Type B askoi, as well as the blackened head that appears on some of the vases of this latter type (Fig. 8). On the second UM bird-askos, however, the black head may have orginally shown an eye like its counterpart, but one that was painted in white directly on the black ground. The more feathery look of Type A.1 bird-askoi, already a far cry from the rendering of the wing and body feathers on the duck-askoi of the Clusium Group, becomes all the more schematized in Type A.2, being composed of purely decorative elements totally divorced from any reference to feathers, i.e., meander or key patterns, zigzags, wave motifs, and the like.

As mentioned earlier, the body of bird-askoi became progressively deeper so as to reach the distinctive shape for the examples classified as Type B (Figs. 8 and 9). There exists an undeniable continuity between the vases of Type A and Type B in the concept of a bird, but the indication of the plumage has become markedly more simple and cursory in execution. Furthermore, the glaze-paint is no longer a consistent deep black, but ranges from exceedingly thin and washy to dense. An example of a Type B bird-askos in the Louvre (Fig. 9) is outstanding as a variant which leads to an entirely different and culminating type of the series. Actually, this ‘new’ bird-askos type is better known as a ‘spout-tail askos’— a vase shape occurring in South Italian (Apulian) pottery as early as the 4th century B.C. (Fig. 10). This ‘metamorphosis’ from bird-askos to spout-tail askos may be seen by comparison of the Louvre vase (Fig. 9) with the earlier mentioned Louvre askos (Fig. 8); note the replacement of the filler spout on the latter askos by a small pointed or knob-like tail on the former vase. More importantly, the duck’s head (see Fig. 8) has been substituted by the filler spout— a feature which may not be apparent at first due to breakage evident in the illustration used for Fig. 9.

Because the bird-askoi classified respectively as Types A and B are so distinctively different in their shape and decoration, there is good reason to believe that they reflect two separate centers of manufacture. On the evidence of proveniences known to me for a goodly number of these vases, together with my acquaintance of the pattern of distribution for ceramic products originating at the two Etruscan centers that had an established pottery production, Tarquinia (or Vulci) may be best associated with the Type A bird-askoi, and Caere with the Type B vases.

The bird-askoi, to which the two examples in The University Museum unquestionably conform, may leave much to be desired as to their artistic merit when compared with earlier duck-askoi of the Clusium Group. Nevertheless, they are imbued with a particular charm and interest. To the field archaeologist, at least, they prove especially worthy of attention in their wholly or partially intact condition because of the potential information they possess regarding problems of archaeological chronology, and the light they may shed on Etruscan commerce and chronology.