Here is a question: If you were going to organize a three-hour dinner party according to the tempo of human prehistory, at which course would the Neanderthals appear? This is not a trick question casting aspersions on the intelligence of your guests. It is instead just one of the wacky ideas put forth in the Human Evolution Cookbook, written by Harold Dibble, professor of anthropology and deputy director for curatorial affairs at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Dibble, with the help of recipes from Dan Williamson, of Chef Dan’s Culinary Adventures, and illustrations by Brad M. Evans, has put together an informative, tasty, and very silly book designed to offer a tongue-firmly- in-cheek rendition of human prehistory, along with some darn good recipes. They were tested at various archaeological digs around the world, including the one at which Dibble and Williamson are currently working, Pech de l’Azé in France’s Dordogne Valley, near the town of Sarlat.

You don’t have to be a history head to like this book. Even I understand statements like “There is little doubt that the earliest humans arose in Africa, but by about 1.5 million years ago they started getting restless and decided to move on.”

Some of the prehistory lore is indeed suspect — I highly doubt that Obladi and Obladoh are real places in Africa — but the recipes are straight-ahead yummy. I especially liked Serengeti Scavenged Stew, which includes the usual garlic, onions, carrots, potatoes, and red wine, along with at least four pounds of roadkill, freshly scavenged to avoid bacteria. Stew beef can be substituted if decent roadkill is unavailable. By the way, during a three-hour evening representing the span of human evolution to the present, Neanderthals would appear at about 9:50 P . M . along with the main course, the confit de canard and pommes de terres du Perigord. In order to save time, since there is still the appearance of modern humans and the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic to get through, Dibble suggests that guests eat directly from the communal pot, digging in with long-handled trowels or maybe just with their hands. Archaeologists call this “eating in the way of the Neanderthals.” Sounds like a good time to me. Beth D’Addono is a food and travel writer based in Belmont Hills, Pennsylvania. She considers herself relatively evolved, though she has been known to scavenge dinner.

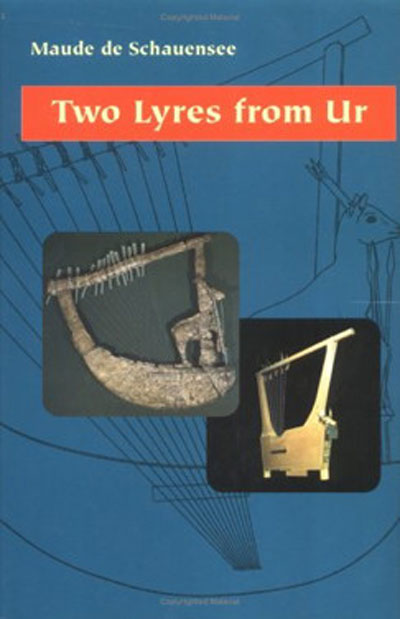

The Lyres from the so-called Royal Graves at UR, the ancient capital of Sumer, are among the most remarkable archaeological finds of the 20th century. They are exceptional both for their preservation and for C. Leonard Woolley’s pioneering archaeological fieldwork in recovering the lyres in the 1920s. In Two Lyres from Ur, Maude de Shauensee tells the story of the lyres’ discovery, curation, and conservation. She also offers a rare view of their construction through computer-assisted tomography and X-ray illustrations.

The author has carefully compiled detailed information, including two appendices. The first features the conservation of a boat-shaped lyre with stag’s head by Tamsen Fuller; the second a conservation report of the bull head from the lapis-bearded lyre by the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s chief conservator, Virginia Greene. The text is amply documented with photographs and drawings, allowing the reader to appreciate in detail the craftsmanship of the third millennium B.C. A few of the images were difficulty to interpret and might have been more readable if accompanied by a metric scale (for example a detail of the boat-shaped lyre showing a faint impression of strings emanating from a slit in the soundbox, plate 15). In discussing possible rigging methods for tuning pegs, de Shauensee refers to an ethnographic example of a lyre from Uganda in the Museum’s collections, which she also uses to illustrate a point about “thin” strings mentioned in cuneiform (Sumerian wedge-shaped writing) texts, as this instrument has strings of varying thickness. Future exploration of what these fascinating instruments would have been like when played would be welcome, building on the information put forth in Two Lyres from Urn. One can only imagine how the delicate flattened copper leaves of the stag’s tree must have quivered, not unlike those of a quaking aspen, when resonating during the boat-shaped lyre’s play.

In general, de Shauensee’s understanding of and appreciation for these important objects shows clearly throughout the book, which is a worthwhile addition to the libraries of scholars of the ancient Near East as well as to those interested in the history of musical instruments.

In the Fall of 1996 a team from the Museum of London Archaeological Service investigated a block along Great Dover Street in the Southwark District of Greater London as part of an analysis of a construction site. They discovered a funerary complex that included one first-century burial that differed dramatically from the rest — a female gladiator, unique in herself, but also accompanied by grave objects of wealth, status, and perhaps Persian and Egyptian origin. Everything about this find was unusual and puzzling.

Who was this woman and why was she here? What sort of life did she live? How and why did she die, and why was she laid to rest differently than others in this spot? Amy Zoll — who is in the Ph.D. program in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania — explores these questions in Gladiatrix: The True Story of History’s Unknown Woman Warrior and in so doing introduces us to a world of new interpretations of ancient life.

In parallel narratives — one speculative, dramatic, and imaginative, one based meticulously on the archaeological and historical record — Zoll helps us understand the facts and significance of the actual grave and the experiences of Roman and Celtic women after the Roman conquest of London in A.D. 43. She also explores the practices of religious festivals and cults throughout the Roman Empire, the psychology of the provinces vis-à-vis Rome, and the changing roles of women, whether in the aristocracy or on the fringes of society.

Zoll’s heroine, Camilla, named for the female Voluscian warrior in the Aeneid, seems modeled on Britain’s warrior queen, Boudica, who nearly drove the Romans from London after protracted battles in A.D. 60–61 as reported by Suetonius and Tacitus and later popularized by Antonia Fraser. The dynamic between Camilla and her fellow female gladiators provides dialogue the site reports would not allow, and this speculation may be the vehicle for a recent Discovery Channel story. The site reports and their links with histories — from Apollonius to Julius Caesar to Cicero and Dio Cassius and Herodotus (though we must be careful of trusting the bearer of lies, who may not actually have met a Scythian) and especially Livy and the Plinys — give us the most reliable data for analysis and interpretation of this woman who died at about the age of 30 around A.D. 60.

Zoll makes excellent use of these sources as she provides background on the rise of public games of mortal combat, the origins of gladiatorial practices in aristocratic funerary rites, and later, the role of gladiators as superstars. These sources also shed light on class-conscious Roman women and the societies that shaped them, the nature of blood sports and the propitiation of spirits of the restless dead by blood offerings, the transmission of cults from one culture to another and, underlying all, the power of Rome and its effect on the London then in its orbit.

How this gladiator may have died, and the significance of her unusual role, most likely as a Celt in Roman London, are springboard speculations that make this brief book, based in scholarship presented accessibly to the nonspecialist, a page-turner in the best detective tradition.

The notes, bibliography, and index are complete and unobtrusive, but the book would have benefited from illustrations of grave objects, site maps, photos of the area, tomb art, sculpture, and writings. Perhaps in the next edition!