The very afternoon of the Barringers’ departure two of our three high hopes were shattered. The Lisa Sounding revealed a pair of enormous marble-faced vats occupying the entire floor area of our cut. Since there were other similar structures in previously dug fourth and fifth century Roman bath complexes at Leptis, we had no difficulty in identifying them. Then to complete our discouragement the Goodchild Trench in the succeeding hour reached the cover slabs of a monumental Roman drain, obviously a part of the same unit. We judged the drain had been designed to carry off a substantial amount of water, as a visiting Royal Marine volunteered to explore it for us and had no trouble in crawling through some thirty feet of its length. Subsequent investigation proved it to rest on sterile soil.

Our last attempt from the sea front trench was to run a diagonal offshoot toward the southwest seeking to avoid further Roman bath remains. This too held disappointment from the Phoenician point of view since our workmen laid bare at a mere five-foot depth a massive well-built Roman terrace. We shortly realized that the terrace derived support from our crude but mysterious floorless, doorless building. Thus the enigma was solved; our walls had been built as protection against the sea and the interior cells solidly packed with a mixed batch of material from earlier dumps–handsome black glazed Greek shreds, a Punic lamp, and fragments of shattered Roman wine amphorae.

The area of these particular Roman installations had in Byzantine times and perhaps later served as a cemetery. A total of twenty-four graves were excavated–the majority of the already mentioned slab variety. We were relatively sure of the Christian identification since a cross was inscribed on the end slab of the third grave. In no instance was there any trace of an object buried with a skeleton. In fact the only curious feature of all the graves dug was the very first one found (presumably undisturbed), in which the skeleton of an adolescent possessed just one arm and one leg, although every other tiny bone was present.

Undaunted by a lack of success in our search for the Phoenician settlement, we sank a fourth trench near the narrowing neck of the peninsula and generally parallel to the Russo cut. Anyone established in this position would have had an immediate view of and access to both the Mediterranean and the Wadi. Italian archaeologists had schematically reconstructed harbors of two Roman periods. The supposed contours of the original land features or those extant in Phoenician times were also estimated by Prof. Bartoccini et al. Thus, we reasoned, our period should be definable between the Neronian level and the water table. In spite of the appellation Athos, after a reputedly “lucky” spotted dog of our acquaintance, this trench too was fated to disappoint. Under a bit of scrappy post-Roman occupation the inland end produced rocky virgin soil. In our Wadi check-pit we were able to break through both the Severan and Neronian pavements, only to reach brackish water less than two feet beneath. Even had there been a Phoenician settlement in this particular area of Leptis, a layer at most two feet thick did not leave us much hope of making a substantial discovery. We began to suspect that the very thorough Roman builders had literally scraped away all shreds of earlier occupations before laying down their foundations.

This all added up to another abandonment, and the time had come to review our position. We still hesitated to give up the port area, and in truth shrank from the problems of attacking the Phoenician city through the major part of the elegant Roman city; any of the Roman structures so disturbed would in due course have to be replaced by us. We soon determined that the only possible remaining site in the harbor vicinity lay on the high ground across the wadi, behind the Temple of Jove and two semi-subterranean stone houses where British soldiers had lived for some time undetected by their enemies during World War II.

We met with a variety of complications in the establishment of this trench, named Adams after the generous donor to our Leptis expedition fund. It meant commuting half a mile between the working trenches on the penninsula to the new location on the south port side, and this through an all but impenetrable “jungle” lining the present wadi bed. The tales of the Libyans citing the twelve-foot red serpents said to inhavit this area were harrowing. Local lore held that if one drank a bottle of native wine before an encounter, the man-biting serpent would die, but the snake-bitten man would survive unharmed! We found it considerably more efficient to have someone with a stick walking ahead shouting, “Attenzione ‘snik’!”

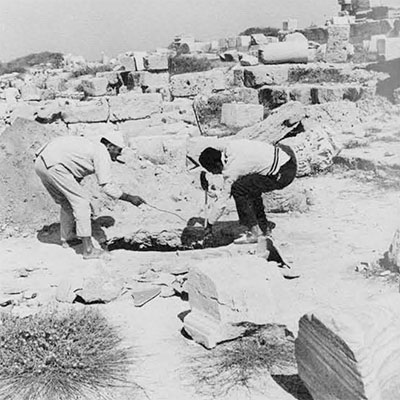

The workmen dug furiously and at a depth of eleven feet two piles of huge jumbled stone blocks in either corner of the trench began to have the unmistakable outlines of hulking buildings. There was again no room to operate. We were pledged not to destroy them and we had not enough time or money at our disposal to excavate them to the bottom, and then hope for Phoenician remains beneath. We were forced to seek elsewhere, yet we had proved nothing regarding the existence or lack of pre-Roman installations in the south harbor area.

Only the Russo Trench was left in operation and it represented a continual frustration. By employing five men there we nearly maintained a balance; four would dig the entire day to remove sand which had falled or drifted in the previous night. The fifth workman brewed the tea required by his companions to keep up their stamina. One very fortunate afternoon we were able to dig for a bit at the end of the Roman harbor pavement. However the sand fell in such quantities during the night that our experience was never repeated. Thus nature reclaimed her own and our last hopes for a large trench were shattered.

Half the workmen had been laid off and five digging days remained. We reasoned that there was little chance of recovering a mass of Phoenician material, but our assignment was reconnaissance, and locate the settlement we must.

One sondage was a square pit near the Severan Basilica between the Wadi Lebda and the oldest part of the Roman city. It was dug to a depth of more than eleven feet and nothing pre-dating Roman glass and pottery was found, before striking the water table.

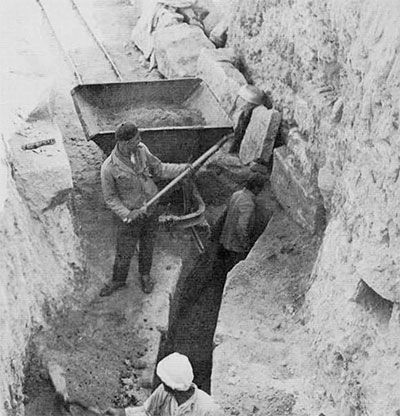

Finally, we knew the British excavators had found Punic graves at a considerable depth below the Roman Theater, inland and west about one-half mile from the harbor peninsula. Our last guess was that the actual town might lie somewhere between the Roman Curia and the First Century Forum where two men could easily roll aside the fallen columns and break through the pavement just beyond the Forum floor. The hole was very small indeed and soon only one man was digging while the other raised and lowered the bucket.

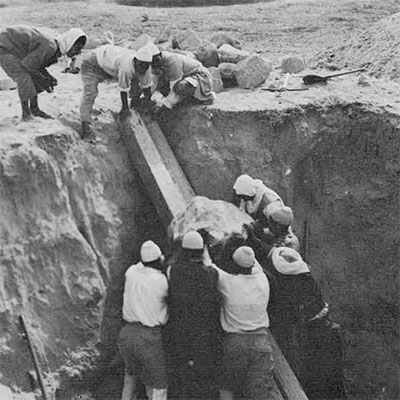

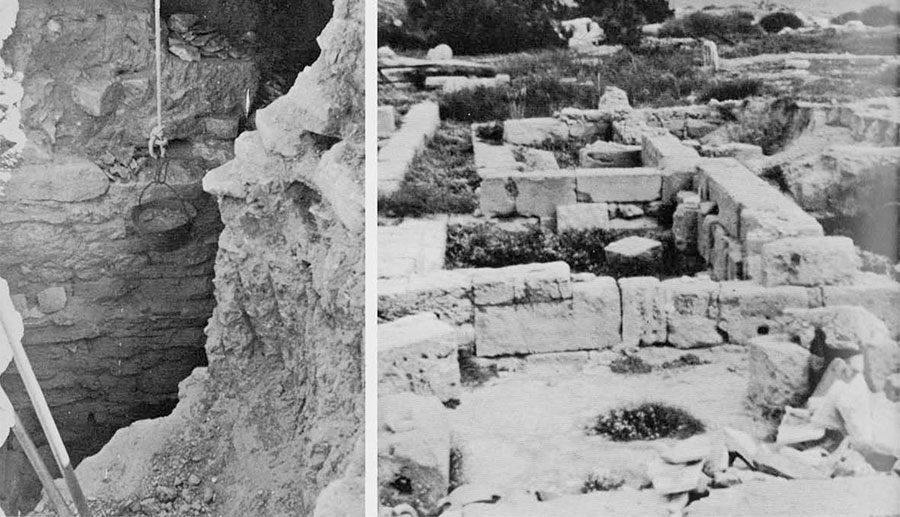

Suddenly we were down four feet and intersecting walls emerged; it was immediately apparent they were not of Roman cut stone masonry. The following day, excavated further and cleaned, it was obvious that the construction was typical of Early Punic walls in the Western Mediterranean. When the corner had been exposed to a height of six feet, we reached a ledge, identified as the floor level. The wall continued down for three more feet beneath the floor and the Corinthian pottery used to date the building was found there.

Naturally we enlarged the area, even though it was necessary to move our dump. At this point our dig was over and I was scheduled to leave Leptis, but this was hardly the moment to break away. Our two workmen agreed to clear more of the walls while I went off to Tripoli, performed the official duties, shipped the luggage, and made appropriate farewells. I was able to taxi back for one last inspection and a day of digging. By then we had exposed twelve feet in length of an Early Punic wall of about 650 to 600 B.C. The intersecting wall was a well-finished and clearly intentional pier running perpendicularly east-west about five feet. In some places the wall was sealed under the Forum level and two additional layers of Roman concrete. The size and plan of the structure indicate a public building, but we really must have more particulars. Western Phoenician architecture, except of a funeral nature, is relatively unknown, especially that of a comparably early date.

At the present time further excavation continues along the lines of our walls, both inside and outside, in the hope of obtaining the total dimensions of the building and details of the plan. If the building runs further north from the Old Forum toward the sea, we expect other major buildings of the same period. This fortunately is an area more or less uncluttered by colossal Roman buildings. In another season it should be possible to expose an important section of the original settlement on the fringe of the Republican Roman city. Such a project would add salient information to our limited knowledge of Phoenician colonization in the Western Mediterranean.