The hunt started nearly two years ago when the Government of Tunisia asked the University Museum to investigate the possibilities of sending an expedition there. At the same time, Mrs. Barringer and I had been asked by my brother, John Paul Barringer, U.S. Counsellor of Embassy in Libya to visit him. Dr. Rainey with Mr. and Mrs. John Dimick went to Tunisia and we agreed to see what might be found next door in Libya.

The object, as in the other University Museum Expeditions was, hopefully, to add a chapter, or at least a paragraph to prehistory rather than to cross t’s or dot i’s. The discoveries of the Phrygian kingdom at Gordion, the hitherto unknown Mannae at Hasanlu, and the whole rise and fall of the Maya capital at Tikal obviously could not be rivaled, but very little is known of the Phoenicians, so a contribution seemed possible. “Delenda est Carthago,” repeated the elder Cato until Rome succeeded in razing that great city to the ground. Leptis, on the other hand, had sought Rome’s protection. Might we not resurrect the western Phoenician civilization by excavating an undestroyed sister of Carthage?

The authorities are still the Bible, the Greek Herodotus (480-425 B.C.), and the Sicilian Diodorus (first century B.C.) The latter gives the story of Carthage and its colonies. The Phoenicians, who are credited with the invention of the first alphabet, have left us little but dedicatory and funerary inscriptions. They had libraries–the Romans specifically destroyed the one at Carthage–but not a book has survived to give us, in their own words, their history, their literature, or their religious beliefs.

The country called by the Greeks, Phoenicia, possibly meaning “palm tree land,” occupies the Mediterranean shore of present-day Lebanon and is 300 miles long by only 7 to 30 miles wide! This narrow passage is part of the principal land route between Asia and Africa and has been fought over for 4,000 years of history and doubtless for millennia before that. Geography practically forced its inhabitants to form individual city states–Tyre, Sidon, Arvad, Byblus, Ugarit, and so forth–and to make part of their living from the sea.

According to their reported accounts, borne out by archaeological evidence, the Phoenicians moved in as part of the westward migration of Semitic peoples of which Abraham’s move from Ur was a traditional part (modern Arabic still has Phoenician words). How soon they took to the sea and when they started to colonize are matters of considerable debate. The classical authors put the founding of Gades (Cadiz) in Spain and Utica, west of Carthage in Tunisia, in the twelfth century B.C. On the other hand, no archaeological evidence of Western Mediterranean colonies older than the eighth century B.C. has apparently been found.

I had been under the impression that Libya contained “tells” (mounds representing successive layers of past cities such as are found throughout the Middle East) and hoped to find one with Punic (western Phoenician) potshreds on its surface. The first step, therefore, was to find what their pottery looked like. We could find nothing in Rome, but the Carthaginians once held Sardinia. A flight to its capital Cagliari, and the kindness of Professor Pesce and Dr. Barreca who are in charge of its Antiquities Department and have excavated several Carthaginian structures, provided the ammunition that seemed necessary. In Libya, however, we found that there were no tells. Civilization buries itself there as elsewhere but (possible owing to the offshore winds) at a far slower rate than the foot a century which I call a very crude yardstick for Iraq. The ground around the Arch of Augustus in Tripoli, the capital, has risen only 3 feet or less than 2 inches a century. The alternative, then, was to look under the great Roman ruins which had been built on the preceding Punic cities of Sabratha, Oea (modern Tripoli), and Lepcis (Roman Leptis) Magna. Ancient Tripoli got its name from these three cities (Tri-Polis).

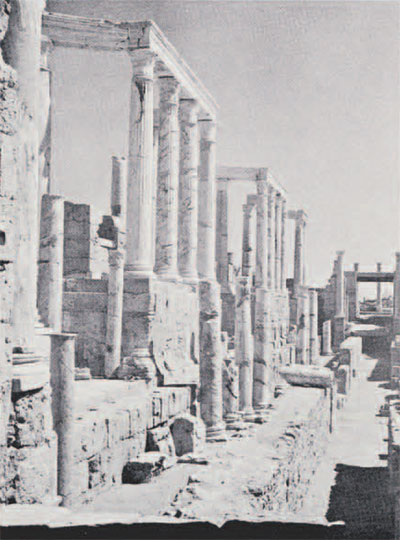

At Sabratha, we saw the sounding which Miss Dorothy Kenyon had made, disclosing a neo-Punic house, but no place to do any worthwhile excavation without disturbing the reconstructed city of Roman days. Tripoli was out of the question because of modern buildings. Leptis Magna, on the Mediterranean shore, 80 miles to the east, seemed the last chance. A square mile of this great Roman city, which had been covered by sand and, therefore, saved from all but a few stone robbers, has been magnificently rebuilt the way its most famous son, the Emperor Septimius Severus (A.D. 146-211) left it. None of the grandeur that was Imperial Rome is left to the imagination.

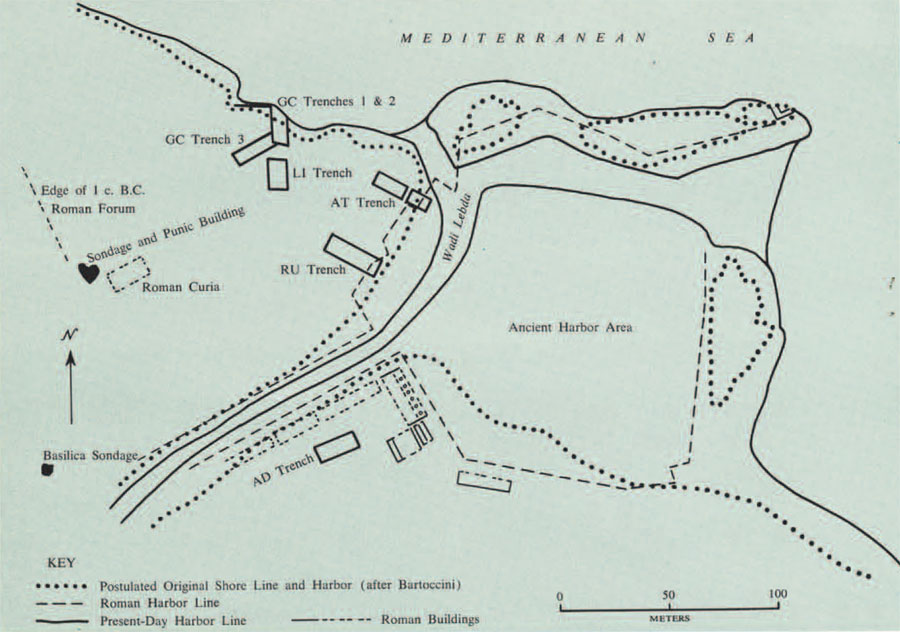

After we had walked through the city on the way to the huge artificial Roman port at the mount of the Wadi Lebda, we came to the three acres of bare ground forming a 20-foot high peninsula between the stream bed and the Mediterranean. This peninsula is the west side of the original harbor. Here, it seemed certain, the Phoenicians had first beached their ships, camped, and eventually built; and there was no reconstruction to hinder excavation! Here, I felt, was ground that must be dug.

I want to emphasize that this was no “original discovery.” The few writers on Leptis have pointed out that the first settlement was probably there, but neither the Italians nor the archaeologists of the British School at Rome who succeeded them, had been enough interested in this particular problem to investigate it. The latter did find Phoenician graves under the Roman theater, so there was no doubt that there had been a settlement somewhere. The facts that many of the Roman monuments are bilingual, that Septimius himself “spoke with a heavy African accent” 300 years after the fall of Carthage, and that his sister, granddaughter of a colonial governor, “had no Latin,” made it clear that the Punic tradition was a strong one. On the other hand, its history might have been like that of French Quebec which increased forty times in size in the 200 years after it fell to the English while also keeping its original language. My own guess was that the location, which made it a great Roman city, couldn’t have failed to make it an important Phoenician one.

Professor Ernesto Vergara Caffarelli of the Department of Antiquities of Tripolitania, who had guided us, was most encouraging about the chances of our being allowed to go ahead, and the Wali (Governor) of Tripolitania proved much interested and assured me there would be no difficulty. We therefore returned to Philadelphia in April, 1959, with high hopes. The Expeditions Committee of the University Museum, on the advice of Dr. Rainey and Dr. Young, head of the Mediterranean Section, approved. The indispensable professional archaeologist was found in Theresa Howard Carter of the staff of that Section who was selected by Dr. Rainey and agreed to take charge of the dig. She had been one of the group that helped us dig Shofer’s cave near Kutztown in 1951 in an unsuccessful attempt to find evidences of early man in Pennsylvania and we were delighted with the selection. Formal permission to dig was asked of the Libyan Department of Antiquities, and Dr. Aneizi, Governor of the National Bank of Libya and the country’s leading scholar, promised his support. We decided to arrive about the end of Ramadan, the four-week Moslem fast during which it is hard to transact business. This was estimated to end about March 25th. We had not allowed for the three-day feast of Bairam which follows it and which is no less difficult.

All seemed arranged and Mrs. Barringer, who was to serve as interpreter in Italian, had already left with our eleven-year-old daughter Lisa. Like her sister Carla the year before, she was “going along for the ride.” Then a cable came advising that the expedition be postponed as Professor Caffarelli was ill in Italy. Our disappointment can be imagined. Fortunately, at Mrs. Carter’s suggestion, Mrs. Barringer called on Professor Ward Perkins, Director of the British School in Rome. He assured her that Signor Francesco Russo, superintendent at Leptis, could take charge of the workmen for us, so we flew to Tripoli.

We called on Mr. Bubakker Zlitny, the head of the Department of Antiquities of Tripolitania. He had never seen the University Museum request which seems to have been “spurlos versankt,” if I may use a World War I idiom. However, we were most fortunate in finding Professor v, former head of the Department for Libya and, at that time, for Cyrenaica, who successfully interceded for us and secured oral permission for us to excavate.

Next day, March 27th, we motored to Leptis and found that arrangements had been made for us to be put up at the local expedition building, from which Mrs. Barringer could get supplies at Homs, a two-mile bicycle ride away. Professor Goodchild accompanied us and helped us pick out the first site which we called the Goodchild cut (GC on the map). This was located along 60 feet of the Mediterranean shore with a 10-foot high bank. Native rock nearly reached the surface at one end, so it seemed certain we could get all the stratification down to the original soil.

Two days later, we settled in and arranged for the hiring of ten workmen and two housemen. Excavation started on March 30th with the “help” of a Decauville Railway. These used to be a great archaeological luxury but, while a car was filled every five minutes and dumped in the sea the first morning, the rate gradually slowed to one every ten minutes and then fifteen as the enthusiasm lagged and the embankment out to sea got longer. “Language difficulty” was illustrated when I tried to explain to the foreman the rate of movement on my wristwatch and was understood to have asked that work continue through the two-hour siesta and then stop for the day! We ran the base line for a survey of the peninsula that afternoon.

The next day was a high point. A structure gradually showed up in the face of the cut. At an angle between the wall and a buttress lay a Punic lamp; and Greek potshreds, such as the Phoenicians used, lay on the bottom under Roman pottery. The dry stone masonry was rough and unlike the usual Roman workmanship. Could we have found a pre-Phoenician, Bronze Age, building? Disillusionment came gradually over the next week or ten days. The structure had no doors; it had no floor. It covered the whole face of the cut and was obviously, as Signor Russo suspected on the fourth day, a Roman foundation. The pottery evidently came from a dump that had been used as filling.

In clearing it, a Byzantine (about A.D. 500) child’s sarcophogus was disclosed 3 1/2 feet below the surface. Like all the burials we later found, the body was laid on the ground with flat stones forming the sides, ends, and lid of a rude coffin. This was the first of several–clearly a graveyard.

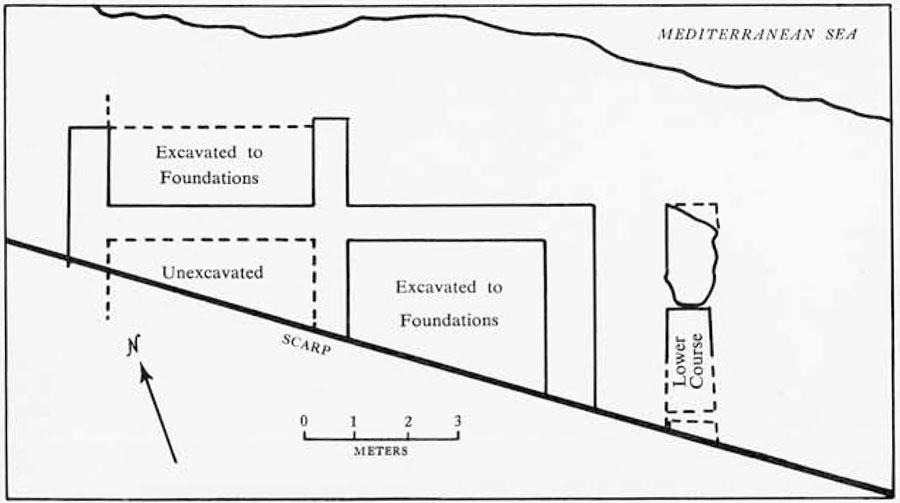

Based on the experience of these two days, we decided we could handle another ten workmen and opened a new cut named Russo (RU) for our superintendent, on the Wadi side of the peninsula opposite the Goodchild one. Within a day, this bottomed on an impenetrable, 2-foot thick, Severan cement pavement and we drove inland along the top of it into the 12-foot high bank of the Wadi. Across the pavement lay two walls, 5 feet apart, one of them with a fallen Roman column as a doorstep. A Byzantine shepherd had re-used it and other stones from Roman structures to make a sheepfold. At a higher level was his similarly constructed watering trough. He had even laboriously cut through the pavement to sink a well.

As the narrow face now available in the Goodchild cut could not employ all the men, we started a 30 by 30 foot sounding (which we called Lisa) on the high ground behind it. At a depth of little over a foot, we encountered several sarcophagi built like the Byzantine ones but with skeletons in better condition and lying on their sides with the heads facing southeast. We then penetrated ten feet of sterile sand.

On April 10th the site was visited by 350 British tourists from an archaeological cruise ship, led by Sir Mortimer Wheeler and Professor Ward Perkins, who were very helpful to us. The next day we started home, leaving Mrs. Carter to continue the exploration. Our hopes were still high. The Goodchild cut was about to break through the foundation and we should get below the Roman layer in a few days. The Russo cut must shortly reach the end of the Severan pavement and enable us to go down there, and the Lisa sounding had only five feet to go to reach the original ground level.

On my return to Philadelphia, I found the April to July 1960, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. It contained an article by Rhodes W. Fairbridge, Professor of Geology of Columbia, who has specialized Carbon-14 dating of recent sea levels. If his figures are right, the ocean was up to 10 feet higher from 600 to 100 B.C. If this is so, and if the coast of Libya hasn’t independently risen or fallen, our peninsula could have been a mere reef washed over by any storm when the Phoenicians came. The obvious place for them to have settled suddenly looked far from obvious! During the Roman and Byzantine periods, the level was up to 10 feet lower than at present which would account for all the structures of that period and might well indicate we would find sterile soil underneath them. The outlook was suddenly gloomy. A welcome contribution to the excavation by the James S. and Marvelle W. Adams Foundation of Greenwich, Conn., which would enable us to extend the exploration, was the only bright spot.