In the summer of 1957 I had the pleasure of visiting the anchorages of Captain James Cook in the Society Islands. With me I carried a copy of the new Hakluyt Society edition of his first voyage. It was a fascinating experience to read the great explorer’s descriptions at the very places where he wrote them. In the summer of 1961, under a Fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, I had the equally fascinating project of tracking down authenticated ethnological material around western Europe which had been brought back on Cook’s voyage.

The three expeditions of Captain James Cook to the Pacific were the first voyages across that ocean to return with scientific data in quantity. Previously the Spanish transpacific voyages had revealed precious little. Probably Mendana and Quiros collected ethnological material at least, but if such collections ever existed, they have vanished. The Manila galleons sailed routes that missed all the islands excepting Guam. The early English (Drake, Dampier, Cavendish, down to Anson) were interested in Spanish treasure, not scientific data and collections. The Dutch, except for Tasman, were more concerned with new commercial routes than anything else. All of these people were doing their jobs as well as they could. They were not expected to be scientists or to make collections.

However, the English forerunners of Cook (Byron, Wallis, and Carteret) aroused the curiosity of the English intelligentsia, especially Sir Joseph Banks who had the sympathy of the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty.

In selecting Cook to command the exploration expedition the Admiralty chose well. A better man could not possibly have been found, combining as he did the qualities of an able and experienced seaman, navigator, hydrographer, with the intellectual curiosity of the scholar. His concern for the care of his men made them safer than if they had stayed at home, something before unheard of for long voyages of more than a month or two’s duration. Not only did he leave little of much importance to discover in the Pacific after his three voyages, but charts made from his surveys were still being used down to the last war.

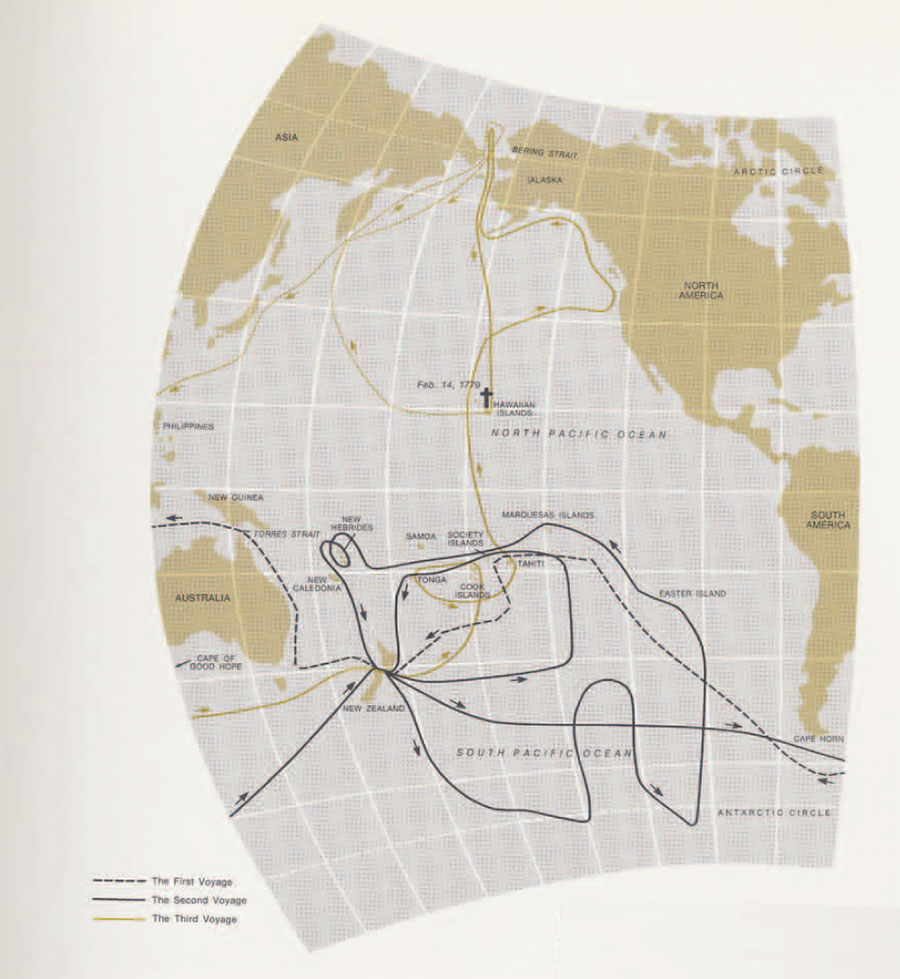

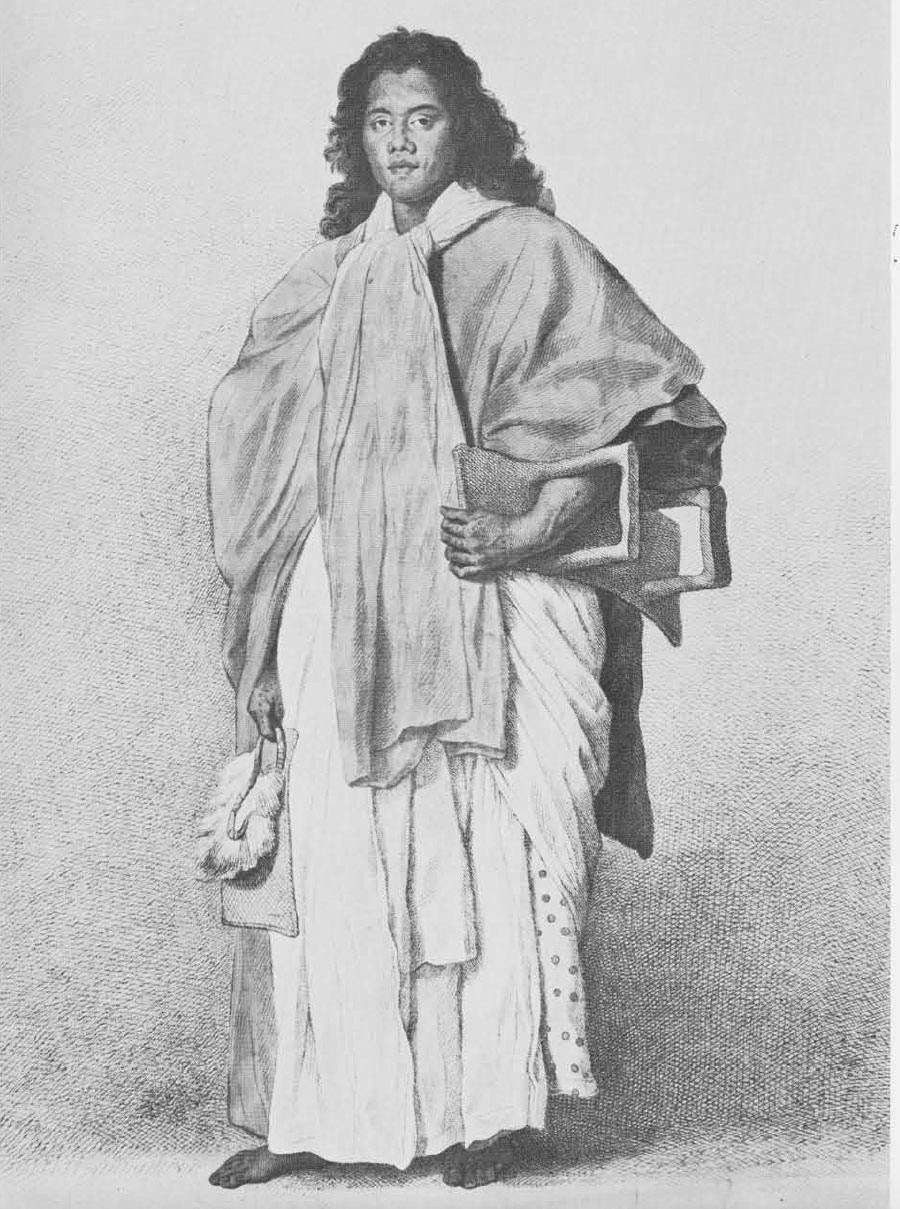

Cook’s first expedition lasted from 1768 to 1771. The primary purpose was to observe the transit of Venus from the island of Tahiti which had been discovered two years before by Captain Samuel Wallis. Following his successful astronomical observations, Cook discovered most of the other islands in the Society group, visited New Zealand, not seen since Tasman was there in the seventeenth century, and made a complete survey of its coast. He then surveyed the eastern coast of Australia, where he was nearly wrecked, sailed through dangerous Torres Strait, and continued around the world home. His second expedition, and the one many consider his greatest, lasted four years from 1772 to 1775 and solved the problem of the great Southern Continent. There was none; but for many years it had been the contention of geographers that an enormous continent existed in the southern hemisphere–temperate, fertile, rich, and well-populated. On this voyage Cook sailed around the world in reverse, entering the Pacific by way of Cape of Good Hope. He made three extended sweeps to the Antarctic ice and two great sweeps up among the Pacific islands, always maintaining his base in New Zealand. In the course of the Pacific parts of the voyage he visited Easter Island, the Marquesas, and Tonga, surveyed the New Hebrides, and discovered New Caledonia. Tobias Furneaux, captain of the Adventure, the companion ship on this expedition, was separated from his commander and arrived home a year earlier. He visited parts of the ocean not crossed by Cook, and while in the Society Islands took Omai with him, a native who became very popular in London society between the second and third expeditions.

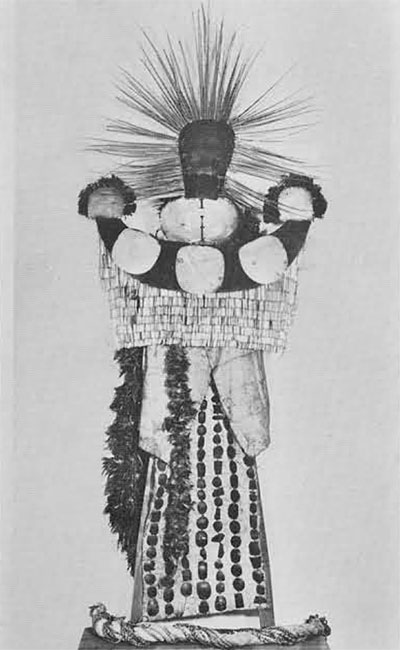

So successful were the first two expeditions that Cook was again selected, although he well deserved retirement, to make an attempt to find the western entrance of the Northwest Passage. This, the third great voyage, lasted from 1776 to 1779. A secondary purpose of the voyage was to return Omai, which he did. Following a stay in Tahiti, Cook sailed leisurely about the Pacific, visiting Tonga and Samoa, discovering minor islands, and then, sailing off to accomplish his primary purpose, made one of his greatest discoveries of all, the Hawaiian Islands which he named for his friend the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty. After making one trip through Bering Strait, he returned to Hawaii for the winter, where he was killed.

Cook’s three expeditions without doubt are among the greatest and most successful scientific voyages ever sent out by any government. Captain Cook will always rank as one of the world’s foremost explorers, both for the amount of work that he did, the number of islands that he discovered, the extraordinary lot of charting and surveying accomplished, and for the well-being of his ships which were so well run that he had no scurvy and very few deaths, except for fever in Batavia, in marked contrast to most earlier expeditions.

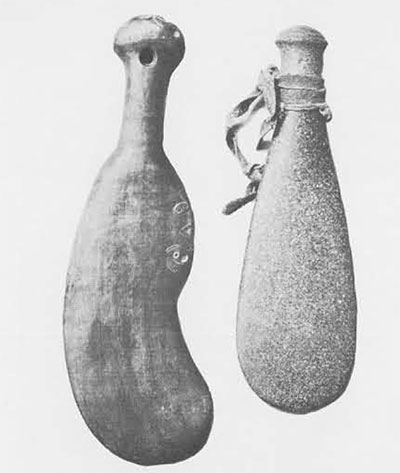

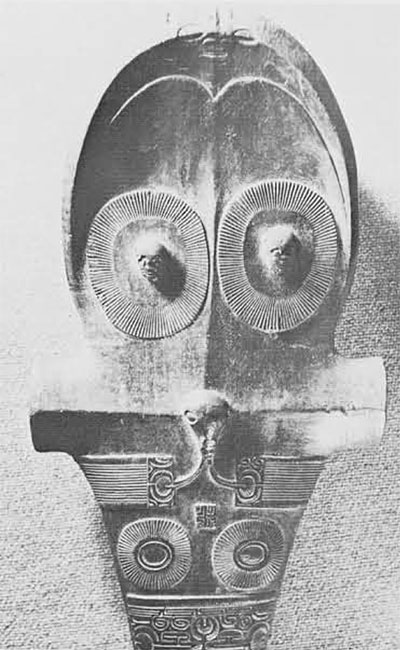

On each of the voyages there was in addition to the ship’s company a scientific staff commissioned to collect natural history and other specimens, and to make drawings and paintings that would be an illumination to knowledge. Great quantities of plants, fishes, coral, and animal life were obtained, and, especially, specimens of the arts and crafts, household goods, weapons and other examples of the material culture of the natives of the various islands. But the collecting of this last class of material was not by any means confined to the scientists, artists, and ship’s officers. Nearly every sailor on board apparently brought back some native souvenirs, and so great was the popularity of the expeditions, catching the imagination, as they did, of all of western Europe, that many of these specimens were sold to collectors and for the cabinets of virtuosos. Even the official collections, or what would seem to be the official collections of Cook, his officers, and scientists, were not necessarily given to the government.

At this time there were several private museums in London to which people paid admissions. Among the most famous were those of the Duchess of Portland, Sir Ashton Lever, and Mr. George Humphrey. The two latter men bought heavily of material brought back on the Cook expeditions. As a matter of fact, all Polynesian specimens in their museums at the time of the dispersal of their collections must almost of necessity have been brought back on Cook’s voyages for no other expeditions from England had gone to the Pacific, excepting those of Wallis, Byron, and Carteret. Cook himself gave material to various interested friends, backers, and scientists.

The task of locating this material, now scattered over the British Isles and western Europe, was an interesting and rewarding piece of detective work. Some of the collections were well known, others obscure, Some had been published in whole or in part, others had never been worked on. Curiously enough the most adequately published collections are Continental rather than British.

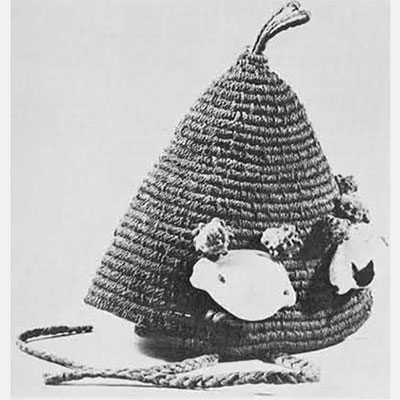

As might be expected, one of the largest collections containing some of the most striking pieces is that in the British Museum. It has been acquired, however, at different times from various sources, including some from the sale of the Sir Ashton Lever Museum. The collection has never been published except for a few individual specimens. There are four or five ethnological specimens with the Cook historical material at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. An authenticated group of four pieces is owned by Mr. Rupert Furneaux of Hayling Island near Portsmouth, which were brought back by his collateral ancestor Captain Tobias Furneaux of the Adventure. Most fascinating of the specimens is the very stool which Omai is carrying in the portrait painted by Dance, that has been reproduced as print. The late Captain A.W.S. Fuller of London, whose collection is now in the Chicago Museum of Natural History, owned two important water color catalogues of specimens done by Miss Sarah Stone who worked for Sir Ashton Lever at the time his museum was sold at lottery in 1785. These books illustrate one hundred and twenty-three Hawaiian objects which, because of their dates, must have come back on Cook’s third voyage. Some of these specimens are now in the British Museum.

The Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Cambridge University contains some well-documented, important material from the Cook expedition. One collection brought back on the Endeavour from the first expedition was given to Trinity College by the Early of Sandwich and appears in one of the early College catalogues. Later the College turned over all its ethnological collections to the museum. A smaller lot of material given by the Earl of Denbigh in 1920 was inherited by him through his first wife, a great-granddaughter of the well-known eighteenth century historian, naturalist, and antiquarian Mr. Thomas Pennant who died in 1828. Pennant received the material directly from Cook.

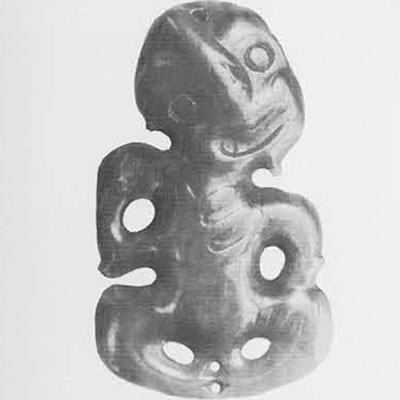

Reposing in the Pitt-Rivers Museum at Oxford is an old and quite large collection from John Reinhold Forster, the German naturalist on Cook’s second expedition. He originally presented it to the Ashmolean Museum from where it was later transferred to its present home. Because of the typological arrangement of material at the Pitt-Rivers the specimens, of which there are outstanding and unique examples, are scattered throughout the collections.

At the National Museum in Dublin there are two lots of material from Cook’s voyages which have become somewhat mixed with the years. One of these was made by James Patten who sailed as surgeon on the Resolution on the second voyage, and the other was made by Captain James King, the author of volume three of the official account of Cook’s third expedition. Both Patten and King gave their collections to Trinity College, Dublin, and they were later turned over to the National Museum. Incidentally, both Patten and King also received honorary degrees from Trinity, presumably as a reward for their generosity.

Two small groups of specimens have landed in Scotland. The most important is at the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow. This collection containing some distinguished carvings was given by Captain Cook to Dr. John Hunter for whom the museum was named. Five miscellaneous Cook pieces have come to rest in the Royal Scottish Museum at Edinburgh.

Finally at the old Yorkshire fishing port of Whitby, where the picturesque town snuggles along the narrow harbor’s edge and climbs the high bluffs on either hand, there is in the Whitby Museums a room devoted to Captain Cook and the great Arctic whaling explorer, Scoresby. Most of the relics here are personal or nautical in nature, but there is a small lot of ethnological material from the Pacific associated with the voyages.

On the continent the Ethnographical Museum in Stockholm contains two important collections, both of which have been published. One made by Anders Sparrman who joined the second expedition in Capetown as an assistant to John Reinhold Forster, was published by J. Soderstrom in 1939 (A. Sparrman’s Ethnographical Collection from James Cook’s 2nd Expedition). The other collection published in 1963 by Stig Ryden(The Banks Collection), was recently identified and catalogued as a collection, made by Joseph Banks and his botanical assistant, Daniel Solander, on the first voyage The documentation on this collection is not so certain as that of the Sparrman collection but the probabilities are that it is correct.

The largest collection of all is at the ancient German university of Gottingen. John Reinhold Forster, a naturalist on Cook’s second voyage, was afterwards a professor at the University of Gottingen. He brought back a collection which he kept in his home and on his death the family sold it to the university. It was bought partly with funds contributed by King George III of England who was also Elector of Hanover. About half of the material, however, came from the sale of the George Humphrey Museum in London. This private museum contained many pieces collected by Forster and they are so marked in Humphrey’s original manuscript catalogue which is in the Gottingen Museum. This was a treasure I had not heard of before. The collection has been described by Dr. Hans Plischke in the guide to the museum but only some of the outstanding specimens are mentioned individually in the general account.

On his third voyage Cook had as an official artist John Webber, a skillful Swiss from Bern who, in his later years, settled in London. He had a fondness for his native city, however, and gave his collection of South Sea treasures to the historical museum there. These have recently been published in part by Dr. Carl H. Henking (Die Sudsee- und Alaskasammlung Johann Waber) in the museum’s Yearbook for 1955 and 1956. The collection includes a famous Hawaiian feather cloak as well as many outstanding pieces.

There are two other large collections. The Museum fur Volkerkunde in Vienna contains one of the handsomest and certainly the best exhibited collection of Cook material. It has also been the most thoroughly published by Dr. Irmgard Moschner (Die Wiener Cook-Sammlung, Sudsee-Teil, “Archiv fur Volkerkunde,” Band X, 1955). This material was bought by members of the Austrian Royal family at the sale of the Leverian Museum in London and presented to the National Museum in Vienna. A similar collection, not so handsome nor so well preserved, is at the Institute for Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence. This, too, was purchased at the sale fo the Leverian Museum by members of the Florentine nobility and it was rather sketchily published in 1893 by Enrico H. Giglioli (Appunti Intorno ad una Collezione Etnografica Fatta Durante il Terzo Viaggo di Cook…di Firenze). One other collection that has survived the ravages of time and war is in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin and consists of about sixty pieces. I have not seen this collection but Dr. Gerd Koch has generously supplied me with photographs and descriptions of all of the pieces.

So far as I know this includes all of the collections extant in Europe of material brought back on Captain Cook’s voyages which are sufficiently documented to be reasonably authentic. I am compiling a complete catalogue arranged by island groups o fall of this material. Therefore, if there are other collections or documented specimens in private hands or in institutions I should very much appreciate information about them.