Eating is an agricultural act,” says essayist, novelist, and farmer Wendell Berry. What does this mean? Berry is renowned for his passionate belief that farming is key to the health of a culture and a society. His assertion forces us to reconsider an act that we generally assume to be commonsensical. Eating is surely about sustenance, health, and commensality, but agriculture?

Eating is an agricultural act,” says essayist, novelist, and farmer Wendell Berry. What does this mean? Berry is renowned for his passionate belief that farming is key to the health of a culture and a society. His assertion forces us to reconsider an act that we generally assume to be commonsensical. Eating is surely about sustenance, health, and commensality, but agriculture?

Berry’s assertion would appear to make sense, but our current globalized food system allows many, especially those of us living in North America, Europe, and metropolitan centers around the globe, to forget that our food comes from the land. As Berry says in The Gifts of Good Land, “Might it not be that eating and farming are inseparable concepts that belong together on the farm, not two distinct economic activities as we have now made them in the United States?” For Berry, the loss of farmers and small farms in most of the United States and, increasingly, around the globe merits not merely a nostalgic reflection on times gone by. He argues that this loss is causing tears in our social fabric and speeding a decline in important cultural values. Berry’s argument corresponds to much recent research by anthropologists. They increasingly witness a decline in local traditions, local livelihoods and local identities due to globalization.

Counter Proposal

When you walk into the newly opened Farmer’s Diner in Barre, Vermont, and sit down, a waitress arrives almost immediately with a mug of coffee. The mug is decorated with the diner’s logo: a farmer on a horse-drawn plow. On the other side of the mug is Berry’s dictum: “Eating is an agricultural act.” Tod Murphy, owner of this newly opened restaurant on the main street of this small town (once called the granite capital of the world), has listened to Berry’s call to arms. He also wants to bring farming and eating back together. He believes that when people know who grows and raises their food, individuals and the community are healthier. This idea is central to Murphy’s entrepreneurial vision. The motto “Food from here” appears on the diner’s placemats, menus, and table tents. Murphy is also fond of saying “Think locally, act neighborly.”

Many of our nation’s founders, most notably Thomas Jefferson, imagined that agrarian values — small landholders, rural communities, local governance — would always be the country’s bedrock. These agrarian values are the inspiration for the Farmer’s Diner. However, the past 250 years have dramatically transformed the structure of our agricultural system. The notion of small, self-sustaining local communities and food systems is no longer part of the than 50 percent of its food from farmers within 100 miles. It means a lot of work, because buying locally takes extra effort.

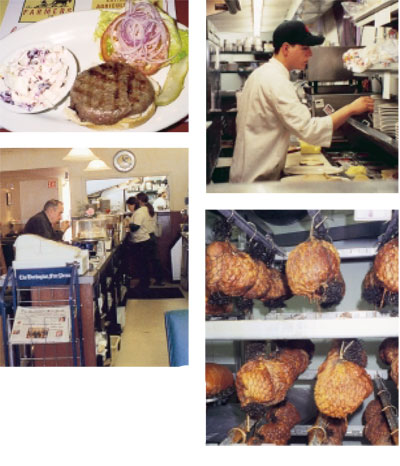

Take the hamburger, the quintessential American dish that’s probably on the menu of every diner in the United States. An iconic hamburger usually has ground beef, lettuce, tomato, often onions and pickles, and sometimes cheese, on a bun. Three hundred and sixty-five days a year. Everywhere. As the McDonald’s Corporation has learned, with billions of hamburgers sold since beginning operation in 1955, Americans love a hamburger. To us, the combination of these ingredients makes an authentic hamburger — the real thing.

A local hamburger, where the ingredients come from within 100 miles of Barre, will be a popular dish with customers and not a very difficult one for the cooks to prepare. Where is the problem? The ingredients. Vermont is a northern state with a cold climate. How do you provide fresh, flavorful tomatoes for your hamburger in January, when all of Vermont is blanketed with snow and the sun is low and weak in the sky? Lettuce poses the same problem.

TOP RIGHT: In the kitchen at the Farmer’s Diner.

BOTTOM LEFT: The restaurant.

CENTER AND BOTTOM RIGHT: Hams in the smoker.

Most restaurants purchase tomatoes and lettuce grown in Mexico or California or Florida during the winter. The produce is shipped to Vermont in large tractor-trailers, traveling from 1,000 to 3,000 miles from farm to plate. To remain true to his vision, Murphy needs a different resolution to the constraints that the long Vermont winter creates. For the time being, he has no choice.

During a conversation in January about the difficult of purchasing local fresh vegetables in the winter, he told me this story. “These days, I go into the diner kitchen, grab a California tomato from the box, and stand on a crate. I drop a tomato on the ground. Nothing happens. No splash. No splurt. The tomato just rolls away.” The cooks are surprised, but he makes his point. Since Murphy is seeking to create the local hamburger deluxe sandwich, tomatoes from somewhere else do not make him happy.

By next year he hopes to contract with Vermont farmers to grow tomatoes and lettuce in greenhouses. Currently there are several entrepreneurial farmers growing tomatoes in greenhouses year round in Vermont and shipping them to markets throughout the East Coast. The juicy, red, ripe, and flavorful tomato grown in Vermont may be available to Murphy by next winter, but his pursuit of local flavor will require more effort and will cost him more money.

Obtaining a consistent supply of local ground beef creates a lot of work for Murphy as well. The bedrock; some see it as an exercise in nostalgia, and others like Murphy — consider it a noble aspiration. However it is perceived, there is no question (as Murphy found out while developing his business) that our system of food production, distribution, and consumption does not support these values.

Bucking the System

Our food system is structured on the fundamental assumption that production should be geared toward creating commodities that can be sold nationally and globally. One in every three acres in agricultural production in the United States today is dedicated to export production. A commodity approach to producing food means that farmers are pushed to adopt the classic formula for economies of scale. The more farmers can consolidate, centralize, and create efficiencies of production, the more commodities (and, it is argued, potential profit) they can produce.

Given this commodity approach to food, the perception that all food should be available year-round, whatever the season, seems reasonable. In that sense, a tomato is like a pen or a pair of socks: always at the store. What does this mean for Murphy’s business? He aims to open five diners and a central commissary in Vermont. The Farmer’s Diner’s mission is to purchase more industrial model of production has been successfully transferred to livestock. In fact, this sector of farming has seen the greatest transformation from the small-scale local system in which farmers raise a few cattle, sheep, or pigs and bring them to the butcher a few times a year.

Decentralizing

Today, a small group of powerful corporations dominates the livestock industry. Tyson Foods, which recently purchased Iowa Beef Producers, is the world’s largest processor and marketer of beef, chicken, and pork products. Four meatpacking companies process more than 75 percent of all cattle slaughtered in the United States. Over 98 percent of all poultry in the United States today is produced by a handful of large corporations. The theme for most of these businesses, as with many large corporations under our present incarnation of capitalism, has been vertical integration. Ownership of all components of livestock production is the goal, from the grains used for feed, to the slaughterhouses and processing plants that turn the live animals into meat for the supermarket, to distribution of the finished product. As the corporate history of one meatpacker proclaims, “IBP’s facilities were more than just slaughterhouses; they were automated meat factories.”

A by-product of this approach is a push toward centralization in production. Vermont, traditionally a state with only a small number of small farmers raising cattle, has not benefited from this shift in production strategies. In attempting to serve local beef in his restaurant, Murphy faced challenges at every level: finding farmers in the area who are still raising cattle and pigs; locating a small slaughterhouse that can accommodate occasional small numbers of animals; and finding a meat processing plant still in operation. During the past 20 years, with the consolidation of the livestock industry, the number of slaughterhouses in Vermont has declined from 20 to 12. Several meat processing plants have closed as well.

As Murphy developed his business plan, he realized he would need to address these obstacles. Otherwise, he says he would never be able to meet his goal of using over 50 percent local products. Murphy ended up purchasing a meat processing plant in a nearby town as well as a truck to pick up all the local ingredients and deliver them to the restaurant. He has decided that to succeed, given his desire to purchase from nearby farmers and support his community, he needs to adopt the business model of his behemoth competitors: vertical integration. In his vision, this approach remains in the community, with the Farmer’s Diner acting as the hub of a wheel, with all the farmers and allied producers and facilities extending outward into the region.

BOTTOM LEFT: Putting the bacon in the slicing machine.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Examining the results.

Vermont Smoke and Cure is the name of the processing plant Murphy purchased to help him supply his restaurant with local meat. When I visited the facility, I was struck by the complex decisions Murphy is forced to make every day in order to preserve his ideals and goals. On a tour of the small plant, we stopped at the smoke box, where bacon is prepared. Larry Tempesta, the plant manager, explained the differences between smoking commercially grown pork belly and the local pork belly brought in by farmers to be processed into bacon: “Locally, every farmer has a different way of doing things.” Some keep their pigs in the barn; some fatten them up with grain right before slaughter; some let them roam freely. There is no uniformity to the pork belly. Commercially produced swine, on the other hand, are bred, raised and slaughtered to be uniform, so it takes Tempesta much more time to brine and smoke local batches to make bacon. The machine that slices the bacon also likes nice, long, even rectangular pieces of pork, which means that the local batches require an extra step; after smoking the pork belly from the farmers down the road, workers need to trim the meat to fit the slicing machine. To keep the business viable given such complexities, Murphy and Tempesta produce three lines of processed meats: commercial, private-label, and Farmer’s Diner brand. Their private-label business is doing very well, as the small farmers in New England hear about the good, small meat processor available again nearby.

Getting Fresh

Do Americans consider eating to be an agricultural act? It does not appear so. Two percent of the total population is involved in farming, and the average age of a farmer is 55. Farming is the occupation in greatest decline. Meanwhile, Americans eat 54billion meals away from home every year, in restaurants, schools, and cafeterias. The restaurant industry captures more of the American food dollar every year: In 2000 it was 46.1 percent, compared with 25 percent in 1955.

These practices are constitutive elements of our culture, revealing our present relationship to farming and eating. Fast, cheap, and convenient: these are the values about food currently in our culture. Food is what you consume on the way to something else, and increasingly it has become less central to our time at home. In fact, we almost exclusively relate to food as a commodity, part of our vast consumer culture. Our energy is spent deciding between brands of cereal and jars of salsa; we have become distant from the many acts involved in making food.

However, our present approach to eating and farming, which emerged after World War II and became our cultural common sense by the 1970s, is increasingly under scrutiny. Both eating and farming have suffered despite the gains in availability and variety in our food supply. Such suffering can be seen in a significant rise in eating disorders and obesity and a precipitous decline in small family farms and low commodity prices for agricultural products. My research into the growing interest from chefs and other food service professionals, as well as consumers, in locally grown and artisanally produced foods shows that people are beginning to see the tremendous benefits to a food system that values the connection between eating and farming, that cares where food comes from and how it was grown or raised.

Tod Murphy decided to develop the Farmer’s Diner business as a result of his own experiences trying to raise and sell veal calves in Vermont. He could find only a tiny market for the premium cuts, and no one willing to purchase the rest. At the same time, he saw how years of farming under the commodity model had transformed practices among farmers he knew in Vermont. “The art and science of farming has disappeared,” he says. Farmers have been forced to become technicians, rather than stewards of the earth. Consumers have lost the connection between eating and farming. The Farmer’s Diner, Murphy hopes, will begin to change how we farm and how we eat.

The globalization of our food system and the consolidation of agricultural production, processing, and distribution have made the idea of eating locally extraordinary, rather than everyday common sense. All roads seem to lead us away from local food systems, like the ribbons of interstate highways where trucks filled with foods from somewhere else travel every day.

Linking eating and farming can return to the forefront the other wonderful ways food plays a role in our lives — pleasure, commensality, sustenance. As a waitress at the Farmer’s Diner said to me recently while I was eating my hamburger at the counter, “I am very impressed with the food here myself. Everything is fresh — it makes a big difference.”

The idea that locally produced food benefits everyone is becoming part of a new type of common sense. As Wendell Berry writes in The Art of the Commonplace: “[C]haracter and community — that is, culture in the broadest, richest sense — constitute, just as much as nature, the source of food. Neither nature nor people alone can produce human sustenance, but only the two together, culturally wedded.” Despite the pressures of industrialization, consolidation, and globalization, there are people like Tod Murphy all over the United States aspiring to this vision of the role of food in American culture. This bodes well for us all.

Amy Trubek has been cooking since she was a high school student. After college, Amy worked in restaurants and eventually went to the Cordon Bleu Cooking School. She then went on to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania in 1995. Her research interests include the history of the culinary profession, cultural ideas about taste, and the contemporary food system. She is the author of Haute Cuisine: How the French Invented the Culinary Profession (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000). Currency, Trubek is a Food and Society policy fellow in a national fellowship program designed to educate consumers, opinion leaders, and policymakers on the challenges associated with sustainable agriculture and local food systems in the United States.