Fragments of Carthage Rediscovered

Discoveries From Our Museum Storerooms

[authors]

The objects in the Penn Museum store rooms—many collected more than 100 years ago—hold many rewarding surprises. Recently, Asian Section Keeper Stephen Lang found—in the Asian Section storage—two fragmentary stone stelae that once were erected in Carthage in the century before Rome conquered and destroyed the city in 146 BCE. One stood in the tophet, the infant sacrifice cemetery, and the other served as a tombstone in one of the great city’s many necropoleis, perhaps the neighborhood known in modern times as “Sainte Monique.” Both small slabs came to the Museum as part of the bequest of Maxwell Sommerville (1829–1904), a sizable portion of which he collected in Asia. He had also donated his famous collection of engraved gems and seals, which includes five engraved Phoenician scarab-seals.

Above: Inscribed Punic stele, front view. 29-130-155.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-130-154

The first stele fragment bears an important inscription in the Phoenician language, as written by Carthaginians in their later days. When the object was cataloged in 1934, the curator at the time, Helen E. Fernald, knowing the characters were not Chinese, relegated it to storage with a note stating the fragment had an “incised inscription in an Indian script.” There the piece remained until Steve recognized the characters for something quite different and special. It seems the Museum holds a small illustration of the history of the city of Hannibal just before it disappeared under the Roman army.

Sommerville had traveled extensively in Asia but also through Turkey, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa. He left a partial memoir of a visit to Tunisia and Carthage in his book Sands of the Sahara (1901). He does not describe the purchase of the stelae, but they are carved in the distinctive gray-white limestone of Carthage and squeezes (latex impressions) of the incised inscription were stored in the Bardo Museum in Tunis. There, they were photographically recorded and published in the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum (CIS 2952) in or just after 1881. Many stelae and other antiquities excavated in Carthage in the 19th century, under various conditions, found their way to the art market.

Marker For a Special Offering

The inscribed stele must have been found in the city neighborhood known today as “Salammbô” (after the title of Gustave Flaubert’s 1862 historical fantasy novel). When complete, the slab had an architectural format, cut at the top into the outline of a peaked roof, like a shrine or tomb with acroteria (ornaments) on the corners. It is now broken across both the gabled top and the bottom line of the formulaic inscription (its present height is 23.5 cm). Below the ornamentation was a seven-line inscription, commemorating an offering made by a man from a very distinguished family. The offering would have been a child.

LRBT LTNT PN Bʿ

L WLʾDN LBʿL Ḥ

MN ʾŠ NDR ḤN[ʿB]

N GRʿŠTRT [HR?]

B BN ḤMLKT H[ŠP]

Ṭ BN ʾŠMN…The translation reads:

To the lady to Tinnit “Face of Ba’-

l” and to the lord to Ba’l Ḥa-

mon, (this is what) vowed Ḥanno [son

of] Ger’ashtart [the ra-

b(?) son of Ḥimilkot the [sufe-

s son of Eshmun]…

This is a standard formula for votive offerings, and probably ended with the phrase “because he [the god] heard his voice,” a standard acknowledgment that a prayer had been answered. The listing of Hanno’s family’s honors over four generations, however, sets this dedication apart from most other Carthage pedigrees: his father Gerashtart was a rab, a high-ranking magistrate of the city of Carthage, and his paternal grandfather Himilkot had been a shofet/suffete, or judge, one of two elected each year. Romans equated the power of the suffetes with that of kings. What was dedicated to Baal Hammon and the goddess Tinnit (Tanit), the “Face of Baal,” was an infant, who would have been cremated and buried beneath this stele in Tinnit’s garden-like precinct. In recent years, the cremated bones buried in little jars in tophets in North Africa, Sardinia, and Sicily have been variously interpreted, with the majority of scholars now convinced that most (but not necessarily all) of the infants offered had died of natural causes or even been stillborn and not deliberately harmed. Rather, they might be understood as being “offered” or dedicated to the god Baal and his consort Tinnit. Tophets have been found in other Phoenician colonies (and one was denounced in Jerusalem) but are not known in the Phoenician homeland or Spain, where Phoenician cities and, later, Carthage established a colonial empire. It is interesting to note that the original stone stele, while not cheap to commission, was no different in size and simple craftsmanship from hundreds of others placed in the Carthaginian sanctuary—even though Hanno (and his baby) came from a distinguished family. Following Hannibal’s defeat at Zama in 202 BCE, many aristocratic Punic families moved back to Carthage from Spain and elsewhere, as the city struggled to pay war reparations to Rome, and it may be that family finances were strained.

The Tophet Rule

The tophets of the Phoenician colonies such as Motya

in Sicily, Tharros and Sulcis in Sardinia, or Carthage in North Africa, were burial grounds for cremated infants and sacrificed animals, set apart from adult necropoleis and linked to the cults of Baal and Tinnit. Inscriptions, as on stelae, refer to the mlk or molk sacrifice, sometimes indicating molk adam (“offering of a human”) or a molk immor, the substitution sacrifice of a lamb. Other urns contain baby animals ritually killed and cremated along with the “offered” (but probably already dead) child. Ancient Greek and Roman accounts of the practice are highly prejudiced, but it appears from a few inscriptions that in special cases live children were sacrificed. The practice continued in North Africa after the Roman conquest of 146 BCE, for instance among the family of Massinissa, the famous king of Numidia (the North African kingdom bordering Carthage to the west) who joined with Rome against his old allies. The controversial debate continues.

A Grave Stele

The other stele, uninscribed and from a different part of Carthage, was carved with a plain gable and the image of a draped female figure set in a niche, perhaps a worshiper holding an incense box, with her right arm raised in pious greeting. It is broken across its base, making its present height 32 cm, and its surface retains a waxy coating probably applied in the 19th century. This was a typical Punic memorial for an adult buried in a regular necropolis and is, again, in fine-grained Carthaginian limestone. Its format is also seen in nearby Sicily and Sardinia. It would have marked a burial, presumably of a woman, in a reserved family plot. Many such monuments were excavated and sold in the 19th century, the early days of exploration of Carthage.

Museum Object Number(s): 29-236-99.2

Museum Object Number(s): 30-33-42

Additional Punic Objects

The last Punic item from the rediscovered Sommerville bequest must have been acquired about the same time as the stelae: packaged with a post-antique bead necklace was a small, brightly colored, glass pendant depicting a slightly comical “demon” head. Core-formed opaque glass was modeled in the shape of a bearded head or mask with bulging eyes and protruding nose, in deep red-brown, decorated with black, white, and yellow drips of opaque glass. The type was made in archaic (7th–5th centuries BCE) Phoenician factories and was popular in Carthage; it may have been discovered in an early Carthaginian tomb, but no documentation accompanied this small item when it reached the Museum. Such ornaments with faces may have served as protective amulets and are sometimes found as offerings with the infant burials.

The Phoenicians and their Carthaginian heirs were famous for purveying such pretty, desirable, and sometimes magical objects to other parts of the Mediterranean and beyond. One related Punic glass bead in the Mediterranean Section, probably 4th century BCE in date, was likely made in Carthage: a blue and yellow cylindrical bead with its center pulled up into three bearded male faces. It has a very interesting provenance: the Maikop Treasure, a collection of rich ornaments and equipment from the Black Sea region and its rich Scythian burial mounds. The Mediterranean Section also preserves a small number of distinctive Punic double- wick lamps and later, Roman lamps from the re-founded city of Carthage, but the head-bead and stelae, even bereft of their original burials, are unique historical items from Maxwell Sommerville’s collection.

The Carthaginian Empire

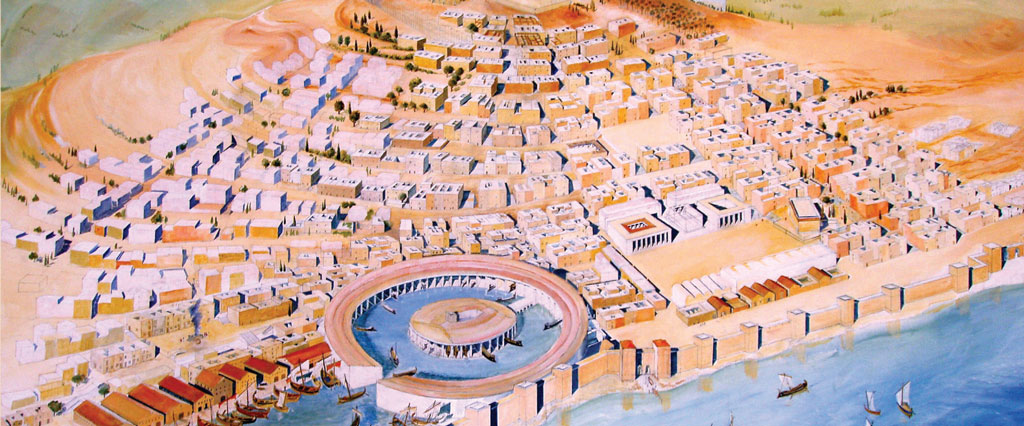

The ancient Mediterranean was peppered with colonial, commercial settlements called by their Phoenician founders “Carthage”—Kart-hadasht, or “Newtown”—but the preeminent colony that soon overshadowed the mother-city Tyre was surely the great city on Cap Bon, on the promontory of modern Tunisia. Phoenician colonial sites and cultures, especially that of Carthage, are termed Punic. Virgil’s epic Aeneid places the foundation, by the queen Dido (Elissa), at the time of the Trojan War (Late Bronze Age), but archaeological activity thus far has identified a 9th-century BCE settlement that rapidly grew to become a maritime empire.

Carthage produced and traded both luxury goods and necessities from the Atlantic to the eastern Mediterranean, including gold, silver, ivory, and glass alongside oil, grain, wine, and fish preserves. Punic statesmen negotiated agreements with Etruria, Sicily, Sardinia, and Iberia as well as neighboring North Africa. One treaty partner that turned on her was Rome, and the subsequent “Punic Wars” (264–146 BCE) that made the Barca (Hamilcar, Hasdrubal, Hannibal) and Scipio (Africanus, Aemilianus) families famous ended in 146 BCE with the destruction of the city by Rome. Much later, Carthage was re-established by Augustus (29 BCE); its position for the grain trade was too important to abandon, and a flourishing city rose on the ruins. The original settlement and the tophet sanctuary were close to the beach with the acropolis (called the Byrsa) behind them; a series of necropoleis surrounded the residential neighborhoods. Since victors tend to write the histories of conflicts, much of our knowledge of Punic Carthage depends upon archaeological evidence.

Exploring Carthage Today

Ever since Roman times Carthage has been a beautiful resort town, where visitors can drift between Punic, Roman, and medieval archaeological sites sprinkled between gardens and the Mediterranean Sea. A little electric train plies between Tunis and the hilltop village of Sidi Bou Said on the coast just west of Carthage (Sidi Bou is where the King Saint Louis sat grieving the loss of Jerusalem in the Crusades). The Punic Admiralty and warship docks and fine houses built in the days of Hannibal, Roman villas with colorful mosaics, amphitheaters and early churches all await your visit to Carthage. Museums in Carthage (on the Byrsa, its acropolis) and Tunis (the famous Bardo Museum) offer displays of artifacts of all periods found in the city and its many tombs. Tunis was a native town in the days of Dido and Hannibal (see Flaubert’s novel about Hannibal’s sister, Salammbo) and has boulevards decorated with green strips planted with scented jasmine that fill with chirping sparrows as night draws on.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Carthage is a short train ride from Tunis, which is very accessible by sea with several regular ferry routes from European ports including Marseilles (France), and Genoa, Civitavecchia, Salerno, and Palermo (Italy). In addition, Tunis features as a stop on many Mediterranean cruise ship itineraries. Flights from the US to Tunis Carthage International Airport usually require a change in a European city, connecting to the national airline, Tunis Air, Air France, or Eurowings.

Penn Alumni and friends were lucky to visit Carthage, as well as the ancient site of Dougga in northern Tunisia, in fall 2019 on a Penn Alumni Travel trip “Ancient Heroes”, hosted and with custom itinerary by Brian Rose, Ferry Curator-in-Charge of the Mediterranean Section.

Penn Alumni Travel invites alumni and friends to explore the world in the company of a Penn faculty host and with the camaraderie of like-minded, intellectually curious travelers. When you’re ready to dream about travel again, or to be added to the mailing list, please visit www.alumni.upenn.edu/travel.

Jean Macintosh Turfa, Ph.D., is a Consulting Scholar in the Penn Museum Mediterranean Section and a specialist in the Etruscan civilization.