Global integration, through tourism and conservation efforts, has shaped resource use in rural Amazonia. The chambira (chahm-BEE-ra) palm (Astrocaryum chambira), once a plant that was considered by locals to be a nuisance, has gained value and economic importance in numerous communities throughout the Peruvian Amazon. Use of the chambira represents an alternative livelihood strategy for residents while also supporting conservation.

It is late morning in the Amazonian village of El Chino, and community members gather under the thatched roof of the small artisans’ market that operates a few times per week for tourists visiting this remote community in northeastern Peru. The market is part of an initiative of a local eco-tourism lodge to address issues of conservation and to provide economic opportunities to the people of El Chino and surrounding communities. On this day, like so many others, the vendors are mostly women selling ornately woven and brightly colored baskets that are made from the fibers of the chambira palm.

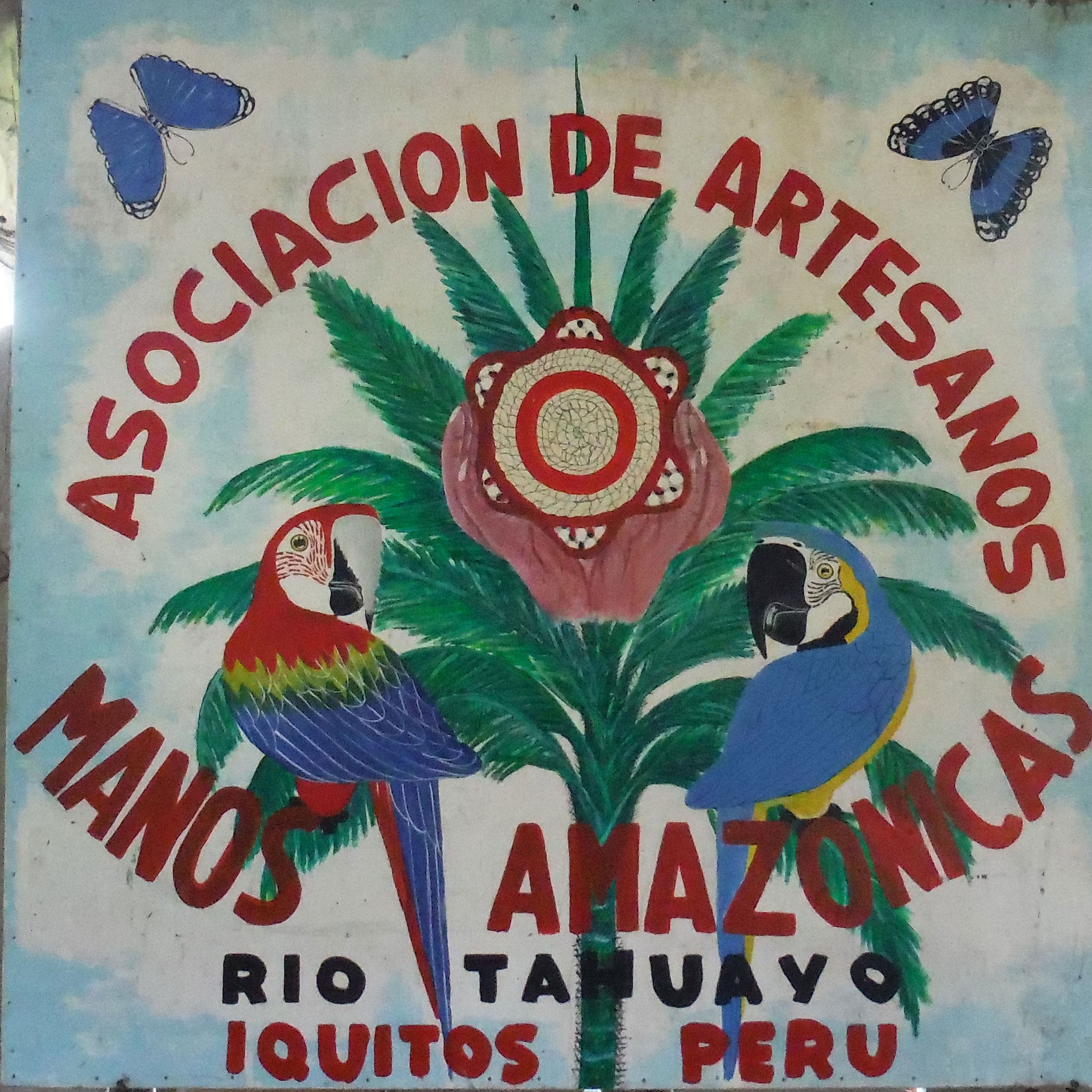

Despite the conspicuous presence of the baskets, it is only within the past 20 years or so that chambira has become a resource of significant economic importance to the people of El Chino and neighboring villages. Coupled with the increase in use, the value attributed to chambira has changed. While chambira has a long history of use by residents, it was predominantly viewed as a problem species and not desirable because of its large thorns and the fact that it flourishes in gardens and cleared areas of forest. However, local perceptions regarding the palm changed due to conservation efforts and the growth of tourism associated with a regional conservation zone called the Área de Conservación Regional Comunal Tamshiyacu–Tahuayo (ACRCTT). The ACRCTT was organized in the late 1980s with insight from local communities as well as support from biologists and researchers working in Peru. Formal establishment of the ACRCTT occurred in 1991.

El Chino and ACRCTT

According to local accounts, the community of El Chino, located along the Tahuayo River, was founded in the early 20th century by a trader who established a trading post near the current village to facilitate the extraction of natural resources for shipment to the city of Iquitos. A one-day boat trip down the Amazon from El Chino, Iquitos is the largest city in the world that cannot be accessed by road. Located in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon, Iquitos is a city surrounded by rivers and jungle and is home to approximately 400,000 people. Its bustling markets are filled with goods harvested from the surrounding forests, rivers, and lakes.

El Chino is one of many villages that fed the growth of Iquitos during the 20th century. Timber, fish, and wild game harvested from the remote region of the Tahuayo were shipped there via river boat to fulfill the needs of the growing Amazonian city. As Iquitos grew, so did pressures on native resources and communities in outlying areas.

The creation of the ACRCTT was a direct response to the overexploitation of forest resources and represented a coordinated effort at conservation led by biologists and residents of local communities. Today the ACRCTT has grown to include more than 440,000 hectares (over 1 million acres) and ten communities whose residents play an active role in management and conservation.

A Thriving Community

Creating Sustainable Conservation

Conservation and development frequently go hand in hand, and one important consideration for creating sustainable conservation is the integration of both environmental and economic concerns. When coupled with conservation, the use of the chambira palm is a noteworthy economic alternative for residents of the Tahuayo. According to local residents, chambira was used minimally in communities of the Tahuayo prior to the establishment of the ACRCTT. It was utilized for making hammocks and fishing line, but its potential as a craft material was not recognized. Now, however, the use of chambira for crafts such as baskets is widespread.

When baskets were first being produced for tourists 15 to 20 years ago, they were significantly less elaborate than they are today. Baskets were also generally created as a supplement to income generated from other activities and were not produced by artisans who were dedicated to the craft of basket weaving. In effect, basket weaving was a “side job” and activities such as hunting, fishing, and horticulture generated more income and occupied more time. Women would weave in their free time and it was mostly an individual activity. Moreover, baskets were marketed only to tourists visiting the nearby tourist lodge and the market took place outside of the local two-room school that also functioned as a type of make-shift community center. Baskets lacked significant adornment and all baskets were natural in color, a process that is achieved by separating the fibers and drying them in the sun.

in the village of El Chino. The palm in the foreground is a chambira palm.

Tourism has increased steadily in the Tahuayo in the last decade and the emergent chambira weaving industry has also grown. It now represents two cooperatives comprised of a total of approximately 50 women and men, across various villages, who are dedicated to the craft. Individual artisans also sell baskets to vendors at the artisan markets that cater to tourists in and around Iquitos.

In addition to an increase in weaving, the baskets have undergone major transitions in the last decade. Changes include elaborate designs with beadwork and the use of native plants such as achote (Bixa orellana) and huingo (Crescentia cujete) as dyes to produce vivid colors. Exported baskets are standardized, making the manufacturing process more difficult. As weaver Doña Elena explained, the difficulty is in creating a consistent design. For this reason, she prefers to produce baskets that are not for export, as more creativity and freedom are possible.

Value and Resource Use

dyed fiber strands.

Two relevant questions emerge from a discussion of basket weaving in the Tahuayo. The first question is how the commodification of chambira is related to value, and the second is how chambira use is allied with conservation. I suggest that these two concerns intersect.

The most obvious, and perhaps most appropriate, application of value is in the realm of economics. The economic impacts, or values, of basket production are notable, and artisans acknowledge basket weaving as making a positive contribution to the household economy. Families of basket weavers have increased their access to cash and consumer goods, as weaving is now coupled with more traditional cash-generating activities like horticultural production and animal husbandry. The result of increased cash is not only greater ability to purchase necessities such as kerosene, gasoline, rice, sugar, and soap, but also the ability to buy consumer goods including generators, flat screen televisions, refrigerators, chain saws, and solar panels. There is a clear economic value to producing chambira weavings, and while it might be easy to think that the value than economic, a deeper analysis indicates something more profound.

Local perceptions of the value of chambira have changed significantly. Wild chambira thrives in fallow fields and secondary forest and many locals described to me the value, or lack of value, that used to be attributed to chambira. Doña Elisa, a weaver for more than ten years, explained to me that she “did not previously know the value…we cut it down, it destroyed the soil.” According to Doña Marta, “We destroyed it…it wasn’t important…we eliminated [it].” A similar perspective was provided by Doña Frida: “The spines are terrible, it is very difficult to work in the fields, the spines get in your hands, we cut it down and we would burn it.” While these commentaries are quite similar, the most profound perspective came from Doña Carmen, who stated simply, “[Chambira] was a plague in our fields.”

The change in the value of chambira encompasses more than a simple recognition of the economic value. The value of conservation is also a relevant issue and the majority of the people with whom I spoke as part of this study acknowledged the importance of conserving chambira as a resource that is worth “protecting” and a resource that is “held in high regard and cared for,” and most artisans indicated a desire to continue to work with chambira. Many residents also grow chambira as opposed to relying on wild harvests. It is something that they desire to have in their fields now and that they actively cultivate.

The global integration experienced by communities of the Tahuayo, through a historical link to Iquitos and a more recent link to tourism, fosters the transformation of existing cultural forms into new manifestations that are appropriate for an increasingly engaged global context. Local-global interactions in the form of tourism and economic integration result in a reconstitution of resource use and value. Value extends beyond the domain of economics, as is highlighted by the cultural emphasis on conservation that has accompanied chambira’s transformation from plague to profit.

DANIEL BAUER, PH.D., first traveled to the Tahuayo in 2000. He is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Southern Indiana.

with dyes made from local plants.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the people of the Tahuayo and to Dr. Paul Beaver, Amazonia Expeditions, and Nelly Pinedo Alvarado for logistic and field assistance. The author also thanks the anonymous reviewers of Expedition and recognizes the University of Southern Indiana Foundation for financial support of this project.

For Further Reading

Berkes, F. “Rethinking Community-Based Conservation.” Conservation Biology 18.3 (2004): 621–630.

Coomes, O.T. “Rain Forest ‘Conservation-through-Use’? Chambira Palm Fiber Extraction and Handicraft Production in a Land-constrained Community, Peruvian Amazon.” Biodiversity & Conservation 13.2 (2004): 351–360.

Newing, H., and R. Bodmer. “Collaborative Wildlife Management and Adaptation to Change: The Tamshiyacu– Tahuayo Communal Reserve, Peru.” Nomadic Peoples 7.1 (2003): 110–122.