Having worked at the 1964 New York World’s Fair when I was a teenager, I thought that I knew a great deal about how things operated in such venues. Much later, I learned through my research at the Penn Museum, however, that, in addition to visiting exhibitions, tasting exotic foods, and buying souvenirs, one could also purchase valuable antiquities. In fact, one of the most popular items in our ancient Egyptian collection—the limestone offering chamber of Kaipure, dating to the late 5th to early 6th Dynasty (ca. 2350 BCE)—is a prime example.

This impressive structure originally comprised almost half of the above ground part of a tomb that the owner, an official of the treasury, had built at Saqqara to ensure a successful afterlife. Today, it still retains almost all of its beautifully carved and painted reliefs and texts. This architectural masterpiece, part of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair), had been on exhibit since the Fair opened on April 30, 1904. A few months later, the Penn Museum learned of its availability for acquisition. It was Mr. John Wanamaker, president of the well-known Philadelphia department store chain, and a manager of the Museum, who made the transaction possible.

The Kaipure Chapel in Egypt

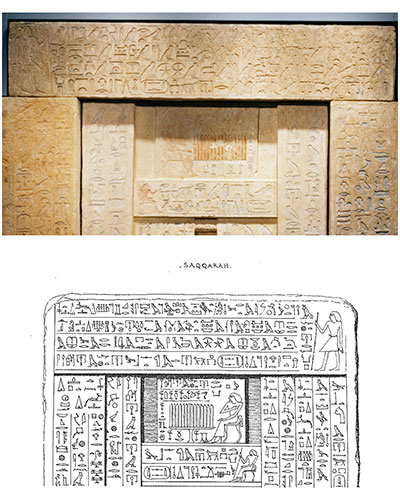

in the Penn Museum. UPM object #E15729. BOTTOM: Mariette’s hand copy of the false door, printed with incorrect orientation.

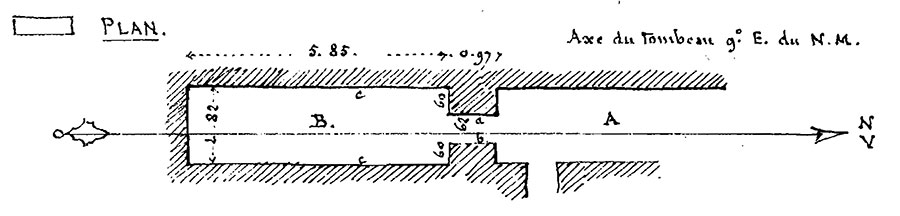

Although early scholars had noticed this tomb, it was Auguste Marriette, Director of Egypt’s Antiquities Service, who first provided valuable reliable details in his published report of 1869. About 20 years later, he conducted a more thorough study in which he pointed out that the surviving parts of the original structure consisted of two rooms and a connecting corridor. He included a rough plan and described the scenes and texts that appeared on the walls. As was the tradition in his publications, he made hand copies of the inscriptions using generalized hieroglyphs rather than more detailed ones that closely resembled particular signs. In addition, the orientation of the texts was incorrect in many passages. Early in the 20th century, photographs were taken of some of the walls of the tomb in situ. Its original location was the Old Kingdom cemetery at Saqqara, in an area north of Djoser’s 3rd Dynasty Step Pyramid. During the following years, reports, descriptions, articles, and references appeared in print. A full publication is now underway.

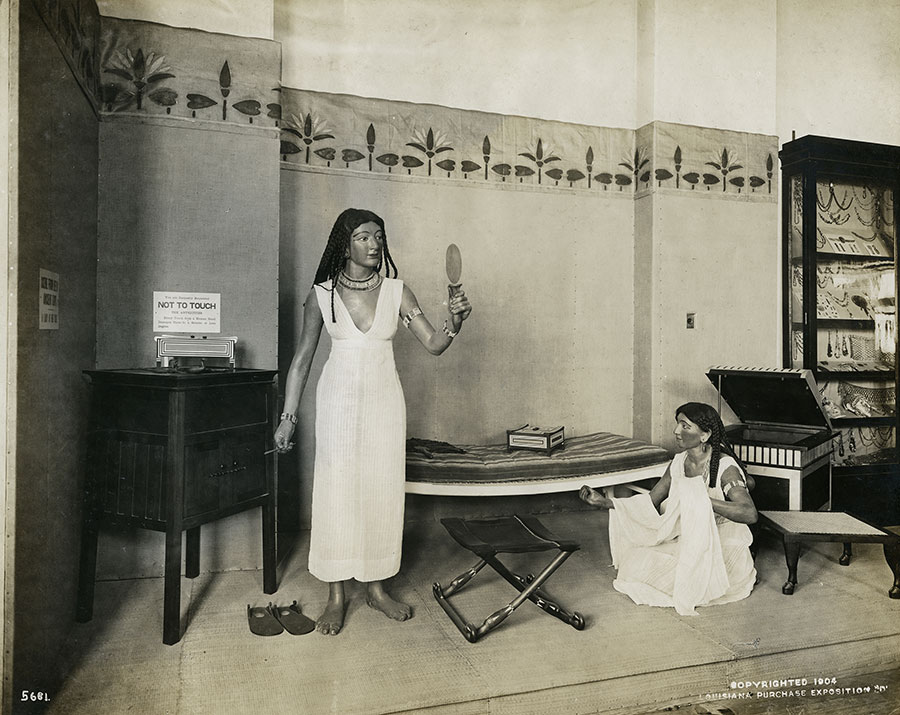

Once officials in Egypt decided to participate in the 1904 Exposition in St. Louis, one of the exhibits they chose to include was focused on ancient Egypt, with the well-preserved remains of Kaipure’s mastaba as one of its highlights. The Anthropology Hall of the Fair housed collections of articles from several parts of the world, including Egypt. Along with the Kaipure structure, ancient Egyptian material on display included mummies, coffins, a sarcophagus, statuettes, pottery vessels, scarabs, necklaces, and shabti figurines. To augment this collection and to prevent the display from becoming too “tired,” as one reporter, prior to the opening of the fair, wrote in the St. Louis Republic (March 6, 1904), the exhibition also had several reproductions of statues and architectural elements, as well as three dioramas with mannequins to illustrate aspects of life in ancient Egypt: beer making, a noblewoman applying makeup, and a nobleman at dinner.

To accompany the exhibit to St. Louis, officials in Egypt had chosen J.E. Quibell, Chief Inspector in the Antiquities Service, who was between his terms directing work in the Delta and Middle Egypt and that in Lower Egypt. He arrived prior to the opening with Herman A. Lawford, Commissioner in the Service in Egypt. Quibell, with assistance from his wife Annie, prepared all of the material for display, composed text and labels, unpacked the objects, placed them in the cases, and arranged the accompanying dioramas. In addition to Lawford’s administrative duties, he also had the responsibility of finding appropriate institutions that might have an interest in purchasing the Egyptian artifacts for their own collections after the Fair had concluded. Not long after the opening, he began writing to different venues in the United States regarding this proposition. On August 8, 1904, he sent a letter to the Free Museum of Science and Art (now the Penn Museum), offering the entire collection, including the dioramas.

Sara Yorke Stevenson Works to Build the Museum Collection

Needless to say, the proposal generated much interest, and it especially captured the attention of Sara Yorke Stevenson, President of the Department of Archaeology at the Museum who, a few years earlier, had begun efforts to increase the size of the ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean collections. A strong supporter of the institution and an influential Philadelphian, she founded the American Exploration Society which financially supported excavations in Egypt.

One of her acquaintances, the renowned British archaeologist, Sir William Flinders Petrie, received funding from the Society, and he provided the Museum, in turn, with artifacts from his excavations. Both the palace of Merneptah and our monumental Sphinx are items that resulted from that collaboration. Ms. Stevenson also utilized reputable agents in Egypt to secure other excavated material. At the end of the 19th century, she organized the first of Penn’s own excavations (at Dendereh), but this endeavor was ultimately not as productive as she had hoped. It would be another decade before a successful effort would take place.

The late summer of 1904 was an opportune time for the arrival of Mr. Lawford’s letter regarding the sale of Egyptian artifacts from the Fair. The Egyptian Commissioner listed the available items: all the material that the Antiquities Service had excavated in Egypt, some casts and reproductions, and three accompanying tableaux. The suggested price for these articles was around $10,000 (approximately $265,000 in today’s dollars), a very good value. The Archives of the Penn Museum contain much correspondence regarding the details of the transaction. Several weeks passed before Penn asked Lawford about the availability of the material, and he responded on October 23, 1904, noting:“…The Egyptian Collection has not been sold as a whole & I am selling it in lots.” Lawford and officials of the Museum exchanged letters and telegrams concerning which objects the sale would include, what the cost would be for packing and transporting the selected material, as well as the arrangement for its clearance of customs, and who would be responsible for which costs. Bargaining and some disagreements extended the time of the negotiations, but on December 15, 1904, Mr. Wanamaker sent a note to Ms. Stevenson confirming his transfer to her of $3,400 “with which the account can be paid when you are satisfied that the goods have come to you in proper order…” For this amount, the Museum was to receive Kaipure’s offering chapel and corridor, a coffin and its mummy, a granite sarcophagus, two other artifacts, and many casts and reproductions. A further amount of $500 was the original estimate for the moving costs, but other miscellaneous charges accrued, so that the total amount reached roughly $4,000. Throughout the lengthy process, Mr. Wanamaker remained actively involved and committed to the project; he even participated in some of the original negotiations in St. Louis in September of 1904.

During late November through early December, Mr. Lawford and an official at the Fair informed Mr. Wanamaker, Ms. Stevenson, and others at the Museum that the collection in St. Louis had to be removed by mid-December. In order to expedite the process the Museum arranged to send its own agent, John Watters, to St. Louis, but his inability to deal successfully with all aspects of the assignment created more delays, which in turn led to more negotiations; sometimes they were amicable, but often they were hostile. At one point Mr. Lawford even tried unsuccessfully to draw directly on funds from Mr. Wanamaker’s account at State National Bank. A few days later, Lawford’s telegram of December 16, 1904 assured Mr. Wanamaker that the Egyptian material was packed and would be shipped upon receipt of payment. Mr. Wanamaker then reauthorized Ms. Stevenson to transfer the money to Mr. Lawford, pending a report from Mr. Watters that “the goods were packed in good order.” The Export Shipping Company acknowledged payment on December 20th, but the same day, the Fair billed the Museum for the packing materials. A week later, Mr. Wanamaker wrote: “the goods on exhibition at St. Louis have not yet cleared the Customs House.” The release of the antiquities, therefore, could not take place on time, and the shipment did not leave St. Louis until January 1905. According to a letter from the Pennsylvania Rail- road Company to the Museum: “a shipment of Exhibits [was] delivered… on January 28th.” Finally, on February 17, 1905, Ms. Stevenson announced to members of the Museum’s Board that the Egyptian collection from St. Louis had arrived.

as part of the 1997 exhibition Searching for Ancient Egypt.

The Kaipure Chapel in Philadelphia

The chapel blocks, stored for several weeks in the basement of the Museum, were due to be moved to the 2nd floor in mid-March of the same year, but the load-bearing capacity of the floor was deemed insufficient, and the mastaba, therefore, remained in the basement for more than 20 years. However, visitors to the Museum could make special arrangements to view the reconstructed structure. When the Eckley B. Coxe Wing was completed in 1926, the Egyptian collection occupied the spacious galleries on the two floors of the new wing, with Kaipure’s chapel on the lower floor. For almost 70 years, the offering chapel remained in that space as one of our most popular exhibitions. In 1996, the Museum began an intensive project to conserve the tomb’s west wall, including its five-ton false door. This monument would become the focus of a new exhibition, Searching for Ancient Egypt, consisting of 146 artifacts from our collection that would travel from 1997–2000 to museums in several U.S. cities. This exhibition reached an audience of approximately 645,000 people.

Today, we look forward to the conservation of the south and east walls; work that represents only one component of the Museum’s ambitious plans for the reinstallation of the entire Egyptian collection. Soon, the completely restored offering chamber from Kaipure’s mastaba will again take its place as a treasure of our collection and an iconic example of the heights of ancient Egyptian culture.

DAVID P. SILVERMAN is Eckley Brinton Coxe, Jr. Professor of Egyptology and Curator-in-Charge of the Egyptian Section.