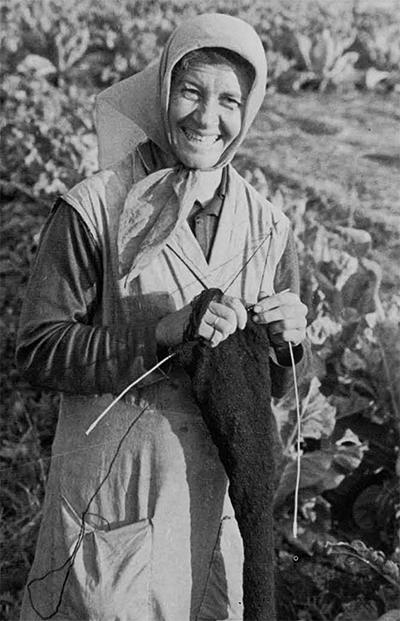

In almost every Greek village black and white kerchiefed women cluster at midday in the cool shade of the stone walls. Like Odysseus’ Penelope, their nimble fingers spin puffy balls of wool into yarn. Despite the increasing popularity of “modern” manufactured goods, the spindle and distaff remain the constant companions of most village women over thirty.

Whether she is herding a flock or gossiping with neighbors, the village woman keeps her agile fingers spinning yards of yarn for blankets, rugs, sweaters and socks. Although some of these items may be produced for sale to tourists, especially in communities having co-operatives or handicraft guilds such as Metsovo in northern Greece, the majority of village women weave and knit articles for their households and for their daughters’ dowries. Young girls, even those who shun the “old-fashioned” distaff and loom, still pride themselves on how high their pile of dowry blankets and rugs climbs.

Although the basic elements of yarn, loom and cloth remain the same, every region of Greece has its own techniques and customs surrounding the process of transforming fleece and goat hair into useful articles. Even within the region, differences in technique and style can be found among villages, the result of diverse history, isolation and fashion. I will be describing the process of weaving as it was taught to me by the women of an upland village in the southern Argolid. This description must reflect the particular customs of this village as well as those of the region.

Paris, 1963, fig. 143.

Roaming Greece’s stony mountainsides are over nine million sheep and goats. The major products of the flocks are meat and milk from which butter and a variety of cheeses are produced. The flocks also produce hair and wool which may be sold or exchanged for pasturage, but most often are used by the family for handwoven and knitted articles. The strong, rough goat hair is woven into sturdy rugs, saddlebags, shepherds’ capes and waterproof coverings for shepherd huts. The sheep, mostly of mountain Zackel breeds, produce a poor quality, coarse wool, This wool, although most suitable for warm, heavy rugs, is used by villagers for a variety of articles—blankets, sheets, sweaters, homespun cloth and knitted underwear. It is sometimes combined with a cotton warp or weft to produce a softer fabric.

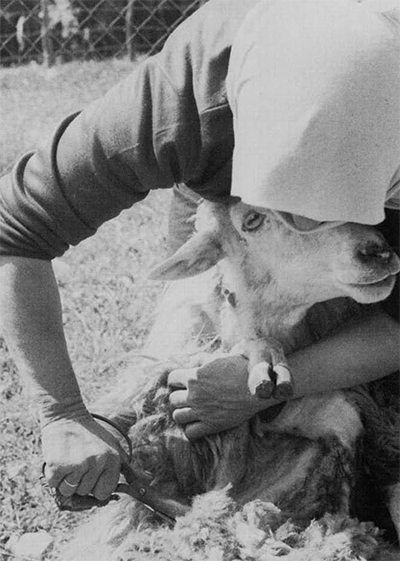

The sheep are shorn of their wool in early May about the time of the festival of Saint Konstantinos. Usually neighbors and kin help each other in turn with the heavy work of shearing, using iron shears, the handles wrapped in rags to cushion the workers’ hands. After being shorn, the flock is sprinkled with blessed water from the church. This custom is believed to prevent the cuts and nicks received by the animals in shearing from becoming infected. Their work completed, the shearers feast on lamb or kid prepared by the flock owner in the traditional expression of gratitude to those who have helped him.

The freshly shorn fleeces are carefully folded and given to women to be cleaned. First hot water is poured over the dirty matted wool, After draining overnight, the still damp wool is then taken to be rinsed in the gentle waves of the Mediterranean Sea. The clean fleeces, still retaining much of their waterproofing lanolin, are spread on the beach to dry in the strong Greek sun.

In the quiet hours of later summer afternoons, women sit in their shady doorways and carefully pick the wool free of burrs and thistles gathered by the sheep in their wandering over field and mountain. As they pull the fibers apart freeing the burrs, the wool becomes light and fluffy. Often, if only a small quantity of wool is required, this is sufficient preparation of the wool for spinning. Larger quantities of clean, picked wool may be sent to small carding machines, located in the larger towns of the region, The old women insist, however, that the softest, finest yarn is produced from wool combed by hand with two wooden paddles that have projecting teeth made from heavy iron nails. Wool prepared in this way is selected to be knitted into underwear, sweaters and socks.

The long side hair of the goats is clipped in late June. The beautiful natural browns, golds, greys and blacks are carefully separated before the hair is prepared for spinning,

Goat hair is not washed, but instead the dirt is forcibly shaken free. Selecting a windless day, the women tie a sturdy rope to a heavy stick weighted down with a stone at each end. The hair is placed under the rope near the stick. The woman takes the other end of the rope and repeatedly whips it up and down. With each snap of the rope light fibers of hair rise and slowly drift to the sides. This fluffy hair is gathered with a pointed stick and gently rolled up, ready to be tied to the distaff. Before the introduction of cement floors, the women had to remove a wooden door to get a firm, flat surface. In summer the village was filled with the rhythmic sound of rope slapping against wood, as quantities of goat hair were prepared for the winter’s spinning.

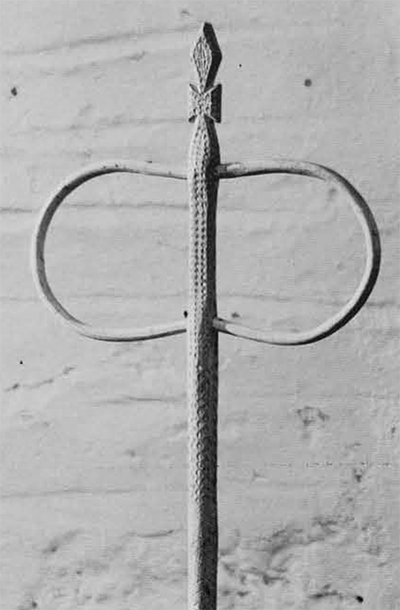

Both wool and goat hair are spun with a simple distaff and drop spindle. The distaff is usually a forked branch from the Chaste Tree (Vitex agnus-castus) a species of water loving bush. In early spring the forked branches are cut when green. The two arms of the fork are then tied together to form a graceful curve, and left to dry in the summer heat, When dry, the two limbs are cut just below the tie and a bundle of wool is placed in the fork. Traditionally, every shepherd carved an elaborate distaff of original design as a gift for his fiancée. Today with few girls learning to spin, only a few talented woodcarvers carry on this custom.

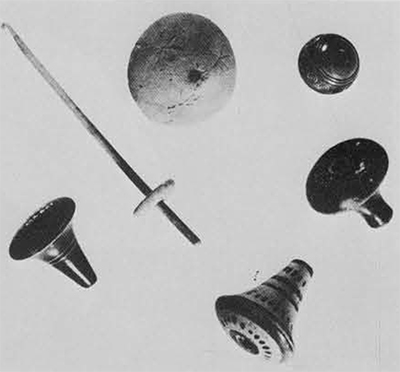

The spindle is a tapered piece of wood about twelve inches long topped with a hook of wire. Empty spindles are weighted with wooden spindle whorls, carved from the cross-section of a tree limb. However, since the introduction of the potato, small green potatoes are being used instead of the wooden whorls. Spindle weights are often lost as the women follow flocks on rocky trails or visit about the village, which may account for ancient stone and clay whorls being found in the most unexpected places. The simple potato is more easily replaced than the hand-carved wooden whorl.

In spinning, the distaff is held tightly against the woman’s body by her left arm. So constant an occupation is spinning, that many women have loops sewed to the left side of their dresses to provide additional support for the handle of the distaff. Wool is spun in a variety of thicknesses, the left hand pulling the desired amount of fibers from the mass of wool and the right hand spinning the spindle in a clockwise direction. Although spun in the same way, goat hair must be kept constantly damp so that the fibers will bind tightly together. The spinner’s fingers, softened by the moisture, become cut and blistered from the coarse goat hair. As the craft of spinning is abandoned, it is no wonder that women stop spinning the goat hair first. Many excellent wool spinners declare they will not spin the troublesome goat hair.

After the wool is spun it is prepared for dyeing, A special stick with two widely spaced branches on one side is used to wind the yarn into a skein to be dipped into the dye pot. Today, with their love of brilliant color, most villagers use commercial dyes. Although in the past dyes were made from walnut hulls, oak bark and wild herbs, generally the natural color of the wool and hair was relied upon for creating the varied patterns, Women complain that dyeing with natural materials consumed too much time and firewood, since it was necessary to boil the yarn for hours on the open fire.

The dyed yarn is ready to be woven after it has been rinsed in the sea to make the dye fast. In recent years villagers have been able to send their spun, dyed yarn to small commercial factories, located in regional centers such as Argos and Tripolis, where the yarn is mechanically woven into heavy rugs and patterned bedspreads. With colorful articles such as these available for their dowries, young girls feel little pressure to labor at the loom. Few girls are learning the art of spinning and weaving, relying on mother and grandmother to spin the yarn needed for the factories. Older women lament the loss of weaving skills and express the feeling that the change is not for the better. They point to great-grandmother’s goat hair rug still being used long after a machine-made one is ragged and full of holes. Although there are a few girls in every village who do weave, either because of strong family traditions, poverty or creative impulse, most looms in the village are old, and no new ones are being built to replace them as they fall into disrepair.

There are two types of looms found in the village—the pit loom and the frame loom, These do not resemble the warp-weighted loom on which Penelope wove while waiting for Odysseus’ return as pictured on Classical pottery. Rather they are simple versions of the multiple harness, horizontal loom used traditionally throughout Europe since the Middle Ages, and familiar to us as the loom of Colonial America.

Both contemporary Greek loom types are made from the wild woods of the mountainside—oak, wild olive, juniper and pine. The wood of old looms glistens from applications of olive oil necessary to keep the wood from splitting in the dry environment of the Greek summer. The pit loom is built into the wall and floor of the house. It uses a minimum of wood in its construction—an advantage in wood-poor areas of Greece such as the southern Argolid. In order to operate the foot pedals, the weaver sits with her legs in a pit beneath the central portion of the loom. In contrast, the frame loom is free-standing. The weaver sits on a bench built into the frame, her own weight stabilizing the loom. Fastened together with wooden pegs, the frame loom may be taken apart for storage as in the summer when room must be made to store the year’s supply of grain in the house.

The working parts of both looms—the comb, beams and string heddles—are identical. Uncompleted weaving, together with the working parts, is easily removed and stored away, carefully covered in the pile of dowry linens. This is done whenever it is necessary to dissassemble the frame or allow a neighbor to share time on the same loom. Not every family in the village owns a loom of its own. Looms are passed from mother to daughter or in the case of pit looms inherited with the house, usually by the youngest son and his wife. Women who have no loom of their own keep their own set of movable parts, to be placed on a neighbor’s loom when they are ready to weave.

Special care is taken with the comb and heddles, since these two parts are difficult to obtain. The combs, made of slivers of reed deftly tied together by hand, are made by itinerant craftsmen who visit the village only once a year to sell new combs or repair old ones. The heddles, made of intricately knotted string, raise and lower the warp of the loom. It is a village custom that only a woman who has learned its construction before her marriage can make new heddles for the village looms. This means that only a few women in the village can perform this task. In preparation for heddle-making the cotton string must be rubbed with the succulent leaves of squash and other garden greens. This is believed to lengthen the life of the heddles and prevent rotting. A special board is used as a form and the coated string wrapped around and tied with special knots.

When a woman is ready to begin weaving, she first selects the kind of warp needed. The warp consists of long threads stretched across the loom; through these, cross threads are woven to create the fabric. Some articles such as saddlebags, tagaria, require a specially spun, two-ply wool yarn. Others such as sheets need fine cotton. Sometimes when one woman does not have enough warp, she combines what she has with one or several neighbors. Later they will each weave articles from the proportion of warp they contributed.

The selected warp is taken to one of the several elderly women who specialize in warping the loom. In her yard she stretches the continuous warp between two pairs of goat tethers or wooden stakes, usually spaced about twelve to fifteen feet apart. Carefully counting each thread, she walks back and forth hundreds of times, crossing the yarn between the pair of tethers at each end. This forms a loop at both ends which will later be slipped over the warp and cloth beams of the loom. When the desired number is reached, she gathers up the lengthy warp and braids it to prevent tangling.

The measured warp is then wound on the warp beam. After the looped end of the warp has been slipped over the beam, the beam is placed in the notch of two forked winding posts that stand in the courtyard of one of the village homes. All village women co-operate in using this one set of posts. As the beam is slowly turned by one person, another pulls on the free end of the warp to keep it taut. In other villages in the region a small sled or tree trunk is used instead, to pull it tight.

Once the warp has been wound on the beam, each thread must be passed through the knotted strings of the heddles and the reed teeth of the comb. Two women sit opposite each other, the heddles and comb suspended between them on the backs of two chairs. Holding the warp beam in her lap, one woman cuts the loop to free the end of the warp and one by one passes each thread through the heddles. The other woman hooks the thread through the teeth of the comb with a knitting needle or thin knife. The completion of this tedious task signals the beginning of the actual weaving, as all that remains is to place the beams on the loom and attach the pulleys and footpedals to the heddles.

Most women enjoy their hours spent at the loom. Although from dawn to dusk they work in the fields, with the flocks, and in the home, women find time to weave as often as they can. In winter the loom is set up in the storeroom. When heavy winter rains make work in the fields impossible, many village women will be found at their looms, hot coals under the footpedals warming their bare feet. In summer, when the freshly harvested grain temporarily fills the storeroom to the ceiling, frame looms may he moved outside under a canopy of vines. In the heat of the afternoon when most of the village is asleep, the rhythmic sound of the weft being beaten into place tells neighbors that a woman is at her loom.

Under the weaver’s deft fingers the pattern grows quickly. Most traditional patterns are handed down from mother to daughter. However, women who marry into the village from other communities bring their patterns with them and often these are added to the village repertoire. Creativity flourishes in colorful rugs with fancy border designs and in special saddlebags, woven to hold traditional wedding breads. These often feature intricate geometric patterns painstakingly laid in by hand.

But regardless of the artistry of a pattern, the finished piece will be judged first on its technical proficiency and its durability. Once the article is in use, the bright colors fade quickly in the strong sun and in frequent washings in the sea. Weaving is seen first of all as the production of useful articles for home and family. The joy of designing with beautiful color and pattern is secondary. For this reason it is not unusual to see a technically perfect article in which the colorful pattern has been completed in a different colored yarn, because the proper color has been used up. The patterns are meant to be enjoyed while the work is still on the loom and later when it is carefully piled with the dowry goods, the best side showing, for all to admire on the daughter’s wedding day.

But although village women appreciate the satisfaction of seeing the colorful cloth grow firm and tight under their hands, soon to be a useful article for their home, young girls refuse to learn the craft of weaving. The introduction of manufactured fabrics has relegated weaving to a secondary place in village society. Whereas before, handweaving was the only way to provide the household with blankets, rugs, sheets and clothing, today it is easy to purchase flashy linens sold by wandering gypsies and printed cotton dresses sold by traveling clothes peddlers. With improved transportation systems, villagers can regularly shop in regional towns and even in Athens. It is not that young girls are too lazy to learn to weave—most girls laboriously ’embroider piles of tablecloths, napkins, and scarfs, and crochet delicate lace doilies for their dowries, It is that the spindle, distaff and loom have been stereotyped as “old-fashioned” and all young girls desire to be “modern.”

Surprisingly, tourism rather than providing an expanded market for handicrafts, has had a detrimental effect on local weaving. Tourists interested in color and pattern first, shun the coarse wool of local products in favor of imitation saddlebags and small wall hangings made from imported Australian wool or, more recently, from synthetics. In the Plaka of Athens, a merchant, who had been a shepherd in his youth, waves his hands in the Greek gesture of hopelessness, “What can I do? I know it hurts our own shepherds, but I must sell what people want. They are attracted by the colors first and then feel the article to see how soft it is.” Often, even the nationally organized weaving co-operatives do not use local wools.

It seems inevitable that this traditional handicraft will be abandoned in most Greek villages. As the skilled older women die, their knowledge of spindle and loom is lost to future generations. Each year there are fewer looms in the villages, and fewer women willing to sit for hours in the damp of winter or heat of summer, just for the joy of weaving. Maria sits at her loom and shakes her head, “The girls just don’t understand. When I am at my loom, I forget to eat; I forget to cook; I forget to sleep; I forget everything but the rhythm of the loom.”

- Winding the warp on the warp beam.

- A frame loom.

- “I forget everything but the rhythm of the loom.”