Some Egyptologists feel that mummies create a false impression of an ancient people preoccupied with death and morbidity, and therefore in some museums mummies are banned from public view. It is true that the ancient Egyptians did not gaze upon unwrapped mummies as museum visitors do, but mummies do exist as an expression of the culture of ancient Egypt (Jonathan Brookner n.d.).

Mummification was widespread during the Empire Period, even among the poorer classes. Herodotus’s fifth century description of three methods of mummification corresponding to one’s economic status may have applied to the New Kingdom as well.

In a period of food shortages a gentleman farmer of Dynasty XI wrote his family, “To be half alive is better than dying outright” (James 1962: 32, p1. 5). Yet in managing his economic affairs this miserly individual, we believe, accumulated fluid capital reserves not for the purchase of more land but for his ultimate burial expenses (Baer 1963: 16-7). A decent tomb and burial tended to be more important economically than high living. At the workmen’s village of Deir el-Medineh some of the most costly items in the village economy were those related to the afterlife (Janssen 1975: pt. 2, ch. 7). A blank roll of papyrus was relatively cheap, one-fifth of a worker’s monthly salary, but one inscribed with funerary material could be costly, equivalent to half the annual income of a skilled artisan. For a set of decorated coffins a worker could pay an amount surpassing his annual income. There is as well much evidence regarding the Egyptians’ abhorrence of death. A common address to visitors to a tomb chapel begins, “0 you who love life and despise death,” and in the mortuary literature there were even spells designed to prevent one from dying a second death.

Death could be personified as a robber “who causes the house to tumble to the ground when he arrives so that all work is come to naught, which one has done as his own” (Wente 1962: 124-6). Thus when a death occurred within a family, the survivors wailed in grief at the funeral with words expressing abandonment, “Where are you going?” and “Where shall I go?” Or their emotions conveyed gloom, “He has gone to the land of eternity and darkness in which there is no light” (Lüddeckens 1943: 37, 135).

Some harpers’ songs urging one to make merry in the face of uncertainties regarding the world of the dead, “from which no one has returned,” exhibit a strong aversion to death, speaking of the destruction of the tombs of ancestors and absence of the pleasures of this life. Other harpers’ songs, however, inveighed against such sentiments: “I have heard those songs that are in the ancient tombs and what they tell in extolling life on earth and in belittling the necropolis … All our kinsfolk rest within it since the very beginning of time. The offspring of millions of millions all arrive there, for there can be no lingering in the land of Egypt, nor is there one who does not reach it. As for the span of earthly affairs, it is the instant of a dream, but a fair welcome is accorded him who has attained the West” (Gardiner 1913: 165-70).

Despite the dichotomy of sentiments regarding life and death in these songs, no one is urged to seek death but simply to accept its inevitability. Prince Hordedef, son of the builder of the Great Pyramid, was advised: “Beautify your house in the necropolis . .. Since it is accepted that death is bitter for us and it is accepted that life is exalted for us, the house of death should be for life” (Posener 1952: 112-3).

An Egyptian tomb comprised two parts: the sealed subterranean burial chamber, wherein were the mummy and the necessities for the next life, and an offering place accessible to living visitors. The notion that the corpse continued to live within the tomb and required burial provisions survived from prehistoric times. Originally the dessicating effect of the sun acting upon the dry sand covering the unembalmed body in a shallow grave was sufficient to insure preservation, but as burials became more elaborate and deeper, such natural dehydration ceased to be effective; so, the process of mummification was developed in the Archaic period. Despite the eventual development of elaborate burials, the sun’s original role in preserving bodies buried in sand during the early periods left its imprint upon the rite of mummification.

The identification of the mummy with the chthonic god Osiris, lord of the underworld, was until the end of the Old Kingdom the privilege of the king and only subsequently gradually extended to commoners. For mummified commoners during the Old Kingdom the solar aspects of mummification were possibly of greater consequence than Osirian beliefs. A Dynasty VI nomarch states that he embalmed his father with oil of the Residence in a piece of red cloth of the House of Life (Derchain 1965; 73-4). The particular type of red cloth used possessed solar symbolism. Another type of red cloth, associated with Osiris, was employed as bandages, so that in the ritual of mummification after the Old Kingdom the use of red wrappings was a means of expressing the union of the solar god Re and Osiris in the deceased individual. The sweat of Re is paralleled to the efflux of Osiris in the mummification process so that the body was not only Osirianized but the deceased in the end became a phoenix, the sun god’s manifestation—”for you are like Re rising and setting without cessation forever” (Sauneron 1952: 8, 44; Goyon 1972: pt. 1).

The dead had to be perpetually provided with food in the public upper portion of the tomb, where before a false door or stela a mortuary priest daily deposited offerings. Funerary endowments and contracts were established hopefully insuring a continuous supply of offerings. Once the food had been ritually consumed by the spirit of the deceased emerging from the false door, it reverted to the caretaker priest as part of his remuneration. Such arrangements, however, could lapse through lack of interest or financial considerations, so in order to maintain the deceased’s well-being, it became common practice to inscribe the chapel with addresses to the living imploring a gift of food, or begging one simply to recite the offering formulae if no food was at hand. It has been said that the dead were thus put into the position of being paupers in their dependency upon the good will of the living (Gardiner 1935a: 27-8).

On special occasions relatives gathered at the tomb chapel to celebrate festivals of the gods in the company of the dead and there was banqueting. These gay affairs reinforced the view that the dead had not really died.

While alive, an individual possessed a sustaining vital force, the ka, which joined the deceased at burial. The ka of a dead person might be manifest in a statue, and it was to the ka that offerings were made. These statues were meant to evoke the ka in the beholder’s mind much as we can picture the image of a departed friend or relative in our own minds.

When a person died, he also became an akh, a spirit similar to our ‘ghost,’ an aspect of the deceased’s personality that operated within the context of society, living and dead. The akhs in the necropolis could function as a netherworld tribunal. If through the ka-concept members of the living society might act for the deceased’s benefit, through the akh-concept the deceased, like a ghost, could act upon the world of the living. When a living person desired specific action on the part of a dead relative, it was to the akh, not the ka, that he would write a letter to the dead.

Such letters might implore the akh to desist from exerting malign influences or invoke the akh’s assistance in instituting legal action in the netherworld court against another evilly disposed akh. The legal relationship between the living and the dead is illustrative of the interaction of the living and dead within the confines of human time and experience.

Within the bounds of human time the dead might ultimately lose identity as tombs were pillaged and destroyed. Thus in the New Kingdom we find these remarks: “A man has perished, and his corpse is (now) dirt. All his kindred have crumbled to dust… More profitable is a book than the house of a builder, than chapels in the West” (Papyrus Chester Beatty IV, verso 3, lines 3-4: Gardiner 1935b vol. 1, 39; vol. 2, p1. 19). Sir Alan Gardiner (1935a) in his classic essay, The Attitude of the Ancient Egyptians to Death and the Dead, praised the writer of these lines as being among the few thoughtful ones who discerned the truth. Yet the thinking behind this advice remains within the confines of human time and ignores other aspects of Egyptian beliefs regarding the dead.

While one concept of the afterlife was continued existence in the tomb, there were other beliefs relating to a totally different realm of existence. A common funerary expression was, “the corpse to the earth, and the ba to heaven.” Often translated “soul,” the ba was another spiritual element, that stood in contrast to body. A ba could reside with the mummy and also leave the tomb as a human-faced bird flying up the burial shaft. It could sit before a little pool in the forecourt of the tomb chapel, or it could fly up to heaven assuming a place in the solar boat, even becoming one with the sun god. The ba was that aspect of the deceased’s personality that functioned outside the natural limitations imposed upon a material body. The corpse remained permanently in the tomb, but the ba was free to move throughout the cosmos.

Mortuary literature often comprises spells pertaining to a host of pleasurable activities for the dead. Many from the Book of the Dead have to do with transformations into the form of the creator god, Atum, or the falcon. The spells from this text have been frequently described as purely magical, and the pietists among interpreters of Egyptian religion have deprecated such bold assumptions as becoming one with the creator god. In commenting upon the future to which Egyptians aspired, Sir Alan Gardiner believed that “the emotions conjured up a brightly coloured picture, but reason, had it been consulted, would have told another tale” (Gardiner 1935a: 31). And more recently Miriam Lichtheim in writing about the earlier Coffin Texts, said:

“Inspired by a reliance on magic, they lack the humility of prayer and the restraints of reason. Oscillating between grandiose claims and petty fears, they show the human imagination at its most abstruse. Fear of death and longing for eternal life have been brewed in a sorcerer’s cauldron from which they emerge as magic incantations of the most phrenetic sort. The attempt to overcome the fear of death by usurping the royal claims to immortality resulted in delusions of grandeur which accorded so little with the observed facts of life as to appear paranoid” (Lichtheim 1973: 131).

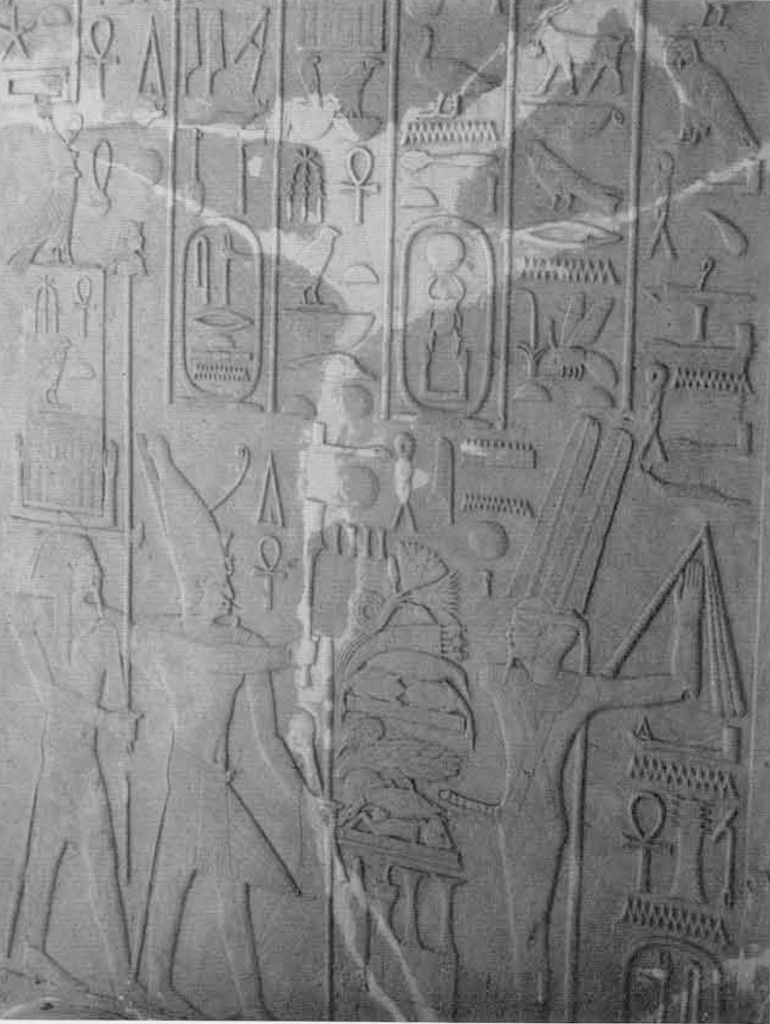

The transformations and multifaceted experiences that the deceased hoped to enjoy were hardly an individual’s emotional responses. Moreover, these aspirations were regularly inscribed in the public portions of tomb chapels, ostensibly to be read by all. Such wishes as “having entry into the mountain of the righteous and voyaging in front of the stars,” “making transformations and being well-supplied in any form he desires,” or “sitting down to play the game senet in the presence of the One who is in his Mehenserpent” (Epigraphic Survey 1980: pls. 67, 73; arta 1968), were often painstakingly and exquisitely carved in the tomb chapels and elaborated upon in the netherworld compendia. The hopes for the afterlife conveyed the religious convictions not of a paranoid individual but of the community who wished to become unified with aspects of the cosmos and to participate in its workings far beyond the work-a-day experience.

Despite obvious pillaging of burials the Egyptian did not follow the rational advice of the learned scribe and cease mummifying the dead. Tomb robbers displayed no fear of the dead as is clear from the following testimony from the end of the New Kingdom:

“We went to rob from the tombs according to the practice in which we were regularly engaged, and we found that the pyramid of King Sobekemsaf was unlike the pyramids and tombs from which we usually went to rob. We … tunneled into this pyramid of this king through its back-part…Taking lighted torches in our hands, we went down below. We cleared away the rubble which we found at the entrance of his recess, and we discovered this god lying at the rear… We found the burial place of Queen Nubkhaas, his queen…We cleared this away also, and we discovered her . . We opened their sarcophagi and their coffins in which they lay. We found this mummy of this king equipped with a falchion, a considerable number of pectorals and jewelry of gold on his neck, and his headpiece of gold upon him, the noble mummy of this king being covered with gold entirely, and his coffins overlaid with gold and silver inside and out and inlaid with every sort of precious stone. We collected the gold … of this god along with … the pectorals and jewelry … We found the queen … [and] we collected all that we found on her as well. Setting fire to their coffins, we took away their furnishings which we discovered with them including objects of gold, silver and bronze. We divided them among ourselves … so that twenty deben-weight (ca. 1820 grams) of gold accrued to each of the eight of us, making 160 deben-weight. … We ferried back across to Thebes (Capart, Gardiner and van de Walle 1936: 171, pls. XIII-XIV).

Incriminating enough as this account is, the culprit, after he had been arrested and confined, bribed one of the authorities with his share of gold and secured his release. Rejoining his fellow thieves, he continued robbing in the tombs until he was finally caught again three years later.

Still, mummification continued and even expanded after the New Kingdom. Gardiner attributed the persistence of such burial practices to the conservatism of the Egyptians. However, the skepticism that was voiced in ancient Egypt against the value of a proper burial tends to reflect the attitude of an individual rather than the sense of the community; and as far as Egyptian religion is concerned, the beliefs of the community were paramount (Bleeker 1967: 9-10). The communal beliefs required ritual processes to be performed for an afterlife. Egyptian religion was strongly ritualistic and sacramental (Assman 1977: 7-43; Bleeker 1967: 11-12; 1973: 16-18). The rites performed upon the mummy together with the recitation of beatifications enabled the deceased to assume a spiritual existence in the afterlife, and perhaps the fate of the mummy was of secondary importance.

The long survival of mummification may have to do with the concept of time. Egyptians obviously experienced the flow of work-a-day time in their daily lives—human time. In Egyptian religion, however, the prevailing notion of time was cyclic as, for example, revealed in the sun god’s daily activity. Even history for the Egyptians tended to comprise repeated events, so that linear time appears to be of less significance than the divine cyclic time.

It was this kind of time, called nhh-eternity, in which the spiritual being of the deceased participated, joining daily with the sun-god Re in his voyage.

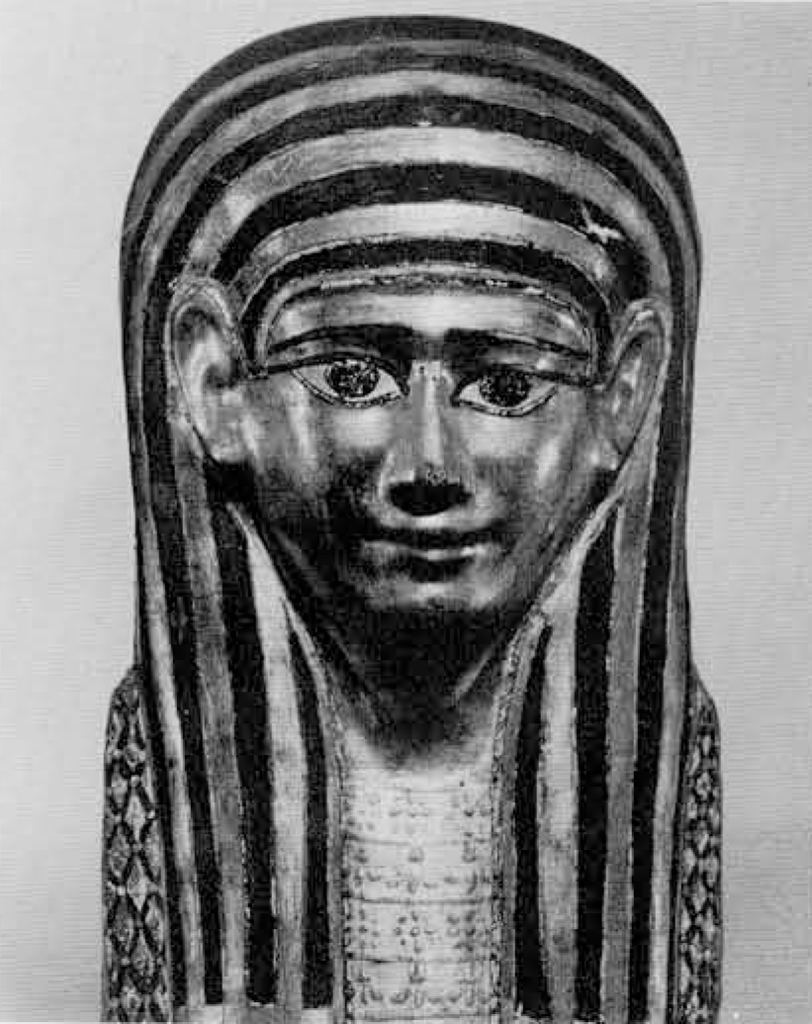

Museum Object Number(s): E2775

Another word for divine time, or eternity, Dt, seems, however, to denote that infinite, absolute eternity divorced from the notion of cyclic time, that related to the god Osiris and the mummy. Dt-eternity was something more absolute and infinite than the mere summation of the discrete parcels of human time proceeding chronologically in linear fashion. It was timelessness itself. Assman (1975) gives other views on eternity.

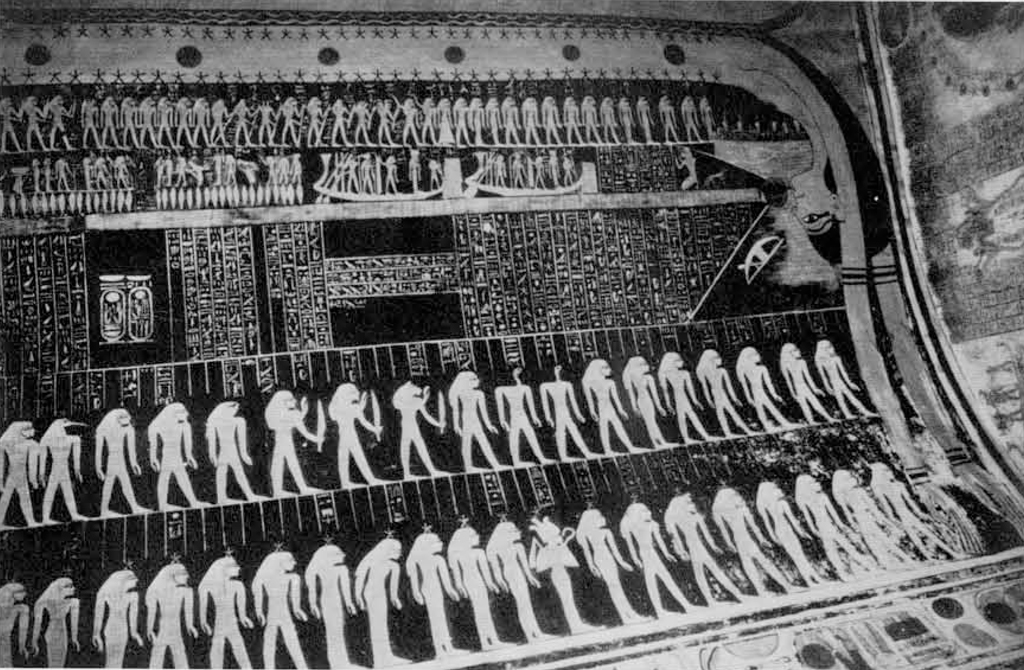

Of some bearing upon the relationship of these two sorts of divine time and of Osiris and Re is the oldest book from ancient Egypt, The Book of Two Ways (de Buck 1961: 252-521, plans 1-15; Lesko 1972). Inscribed on the floor boards of early Middle Kingdom coffins from Bersheh in Middle Egypt, this illustrated cartographic book depicts two routes, one by land and one by water, leading to a common destination. The two-way motif is, of course, attested in other religions, where frequently there is a dichotomy in choosing either the path of righteousness leading to heaven or the path of unrighteousness to hell. However, Egyptian complementary thought patterns, as amply illustrated in wisdom literature tend toward dialectical resolution, not an either-or. As the mummy literally lay on top of the two ways depicted on the bottom of the coffin, these two routes were not alternative ones but were traversed simultaneously toward one common destination. The two ways are described as the ways of Osiris, but they are also heavenly, the day and night routes of the sun. Underlying this composition is the unity of Osiris and Re and their ways, so that the person who knows the spell “will be like Re in the east of the sky and like Osiris within the netherworld” (de Buck 1961: 262; Bergman 1976-7: 51-4).

Associated with the ultimate destination is a text in which the creator god says, “I have spent millions of years (in a separation) between myself and the Weary-hearted one, the son of Geb (i.e., Osiris). (Now) I shall dwell with him in one place. The mounds shall become cities, and the cities shall become mounds. It is one house that will desolate the other house” (de Buck 1961: 467-8).

Museum Object Number(s): 53-20-1A

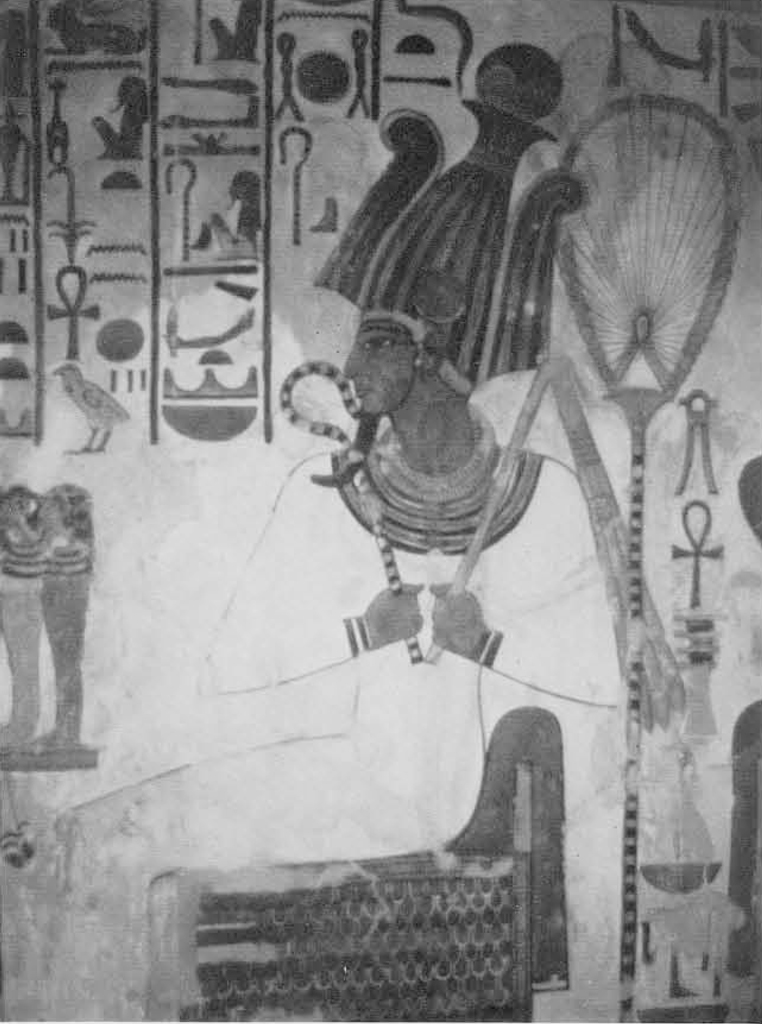

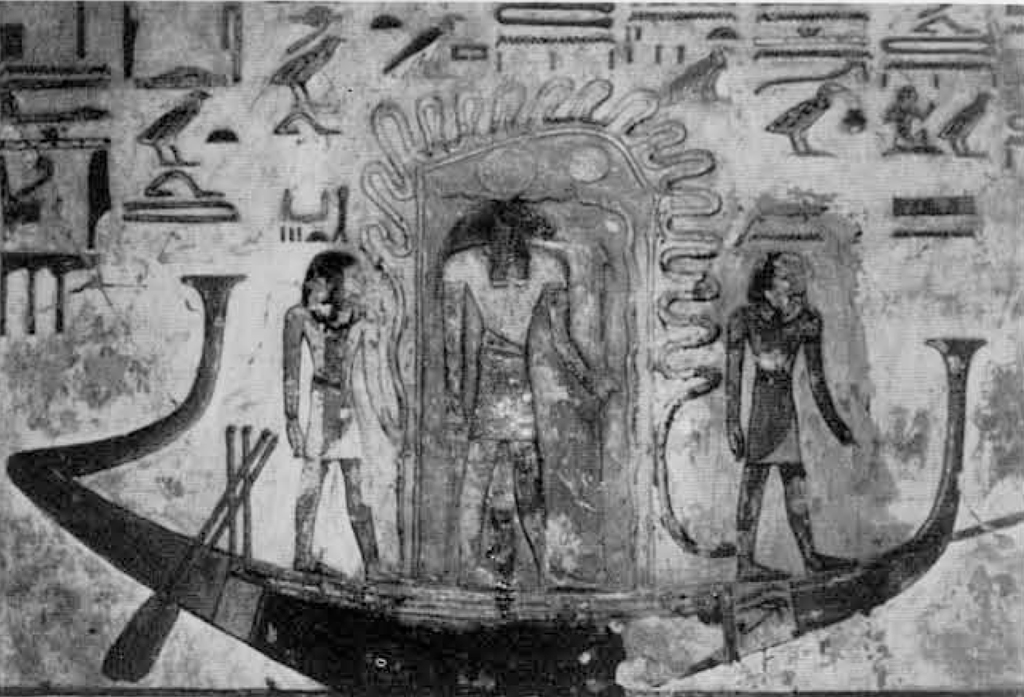

This strange passage is apocalyptic. It marks the end of measurable time, “the millions of years,” and the undoing of created world order, with the result that the sun-god and Osiris become one. The Egyptians, however, did not view the apocalypse like our final judgment day at the end of human linear time. It is a conceptual potential eschatology that could take place at the end of each day when viewed from the aspect of solar cyclic time, or at the time the mummy is laid to rest in the coffin and enters Dt-eternity, timelessness. With the unification of the sun-god and Osiris, there is a point of contact between the absolute timeless eternity of Osiris and the mummy and the cyclical revitalization of the dying sun-god. In the tomb of Queen Nofretari the unified Re and Osiris is depicted as a ram-headed mummy, with the accompanying text, “He is Re, who has gone to rest as Osiris, and Osiris who has gone to rest as Re” (Hornung 1971: 85-7, pl. 5).

The fusion of Re and Osiris is a process whereby at night the sun-god Re in his dying and rebirth becomes one with Osiris, the god who once died and was revivified; thus two worlds of existence were united, and infinite absolute eternity becomes one with the cyclic eternity. Through mummification and burial, and the associate rituals, the spiritual being of the deceased, the ha, could leave the mummy resting in absolute eternity and enter the vast dimensions of the cosmos moving within cyclic time. The fate of the body within the confines of human linear time was inconsequential from the purely religious point of view, which formed the basis of the reason for mummification, for the confines of measured human time were broken and the deceased was placed within the realms of two types of divine time that are related to each other beyond the confines of human experience. Perhaps when the deceased says in one Coffin Text passage (Spell No. 335): “Yesterday belongs to me, and I know tomorrow,” and the explanation is given, “As for yesterday, it is Osiris; as for tomorrow, it is Re” (de Buck 1951: Coffin Text, vol. IV, 184 ff.) and we consider this in terms of the fusion of Osiris and Re, we find ourselves in a timeless present (Pfeiffer 1924: 209; Blakney 1941: 292).

It is also possible that mummification persisted because Egyptian religion in its broadest sense was too inextricably bound up with the concept of death and burial to permit a complete reversal of religious practices in one, the funerary, sector. Through death, men shared with the gods a strong common bond. Egyptian gods could also die. They are frequently represented as mummiform and even possessed burial places in parts of Egypt. An official involved in the restoration of the royal mummies, wrote in a letter which he placed by his own dead wife’s coffin: “The sun-god has departed and his company of gods following him, the kings as well, and all humanity in one body following their fellow men. There is no one who shall stay alive, for we will all follow you” (Cerný and Gardiner 1957: pl. LXXX, verso, lines 13-15. Also cf. Cerný 1973: 370). In a mythical tale the god Ptah says to Osiris, “Now after the manner of gods, so also shall patricians and commoners go to rest in the place where you are” (Gardiner 1932: 58; Simpson 1973: 124).

In fact, the relation between living religion and funerary religion finds expression in a rare statement by the creator god concerning the purpose of man’s earthly existence in the conclusion of the Book of Two Ways: “I have made it so that their (i.e., men’s) hearts should not forget the West in order to make divine offerings to the gods of the districts” (de Buck 1961: 464). Thus concern for the world of the dead, the West, is linked up with the feeding of the gods. To have suspended burial rituals would have meant a thorough revision of the total religious picture in Egypt. But Egyptian religion was altogether too integral a part of national culture to have permitted such a radical change.

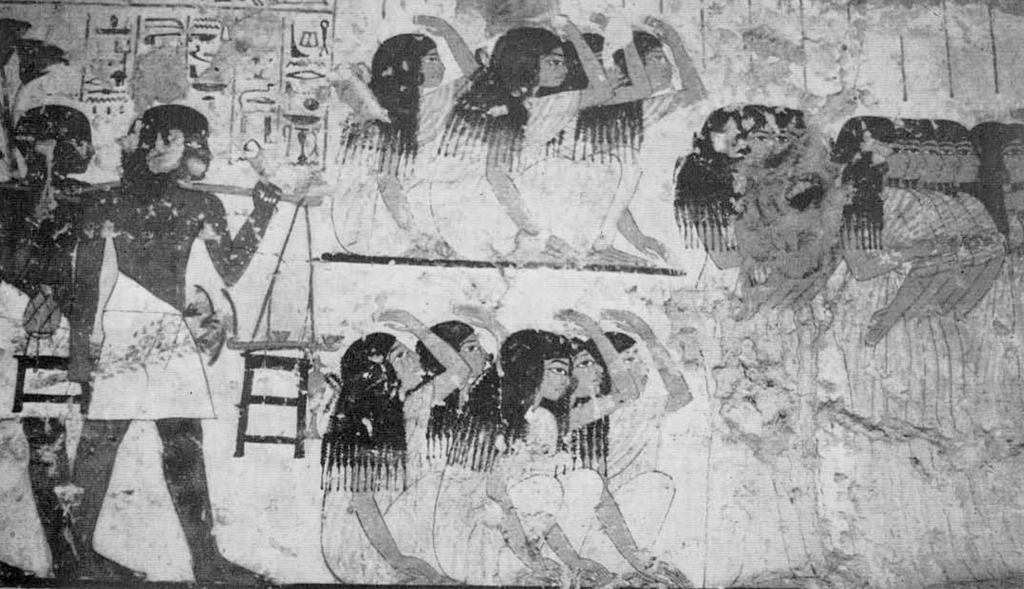

Indeed the duality of solar and chthonic was a major theme not only of Egyptian funerary religion but also temple religion. There were rooms in temples devoted to the solar cult as well as chambers relating to the revivification of the mummified Osiris. In the royal jubilee, as depicted on the walls of Kheruef’s tomb chapel, the two themes are solar and chthonic (Epigraphic Survey 1980: 62-3, pls. 24, 47; Wente 1969: 90-1). In a text accompanying the solar apotheosis of King Amenhotep III we read, “Opened are the doors of heaven so that the god may come forth pure.” This is paralleled by the following hymn from the chthonic ritual, addressed at the erection of the Djed-pillar of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. Sokar in the hymn is a chthonic deity.

Opened are the doors of the underworld, 0 Sokar,

While Re is in the sky rejuvenated. Atum appears in glory while beholding you.

Dazzling are you in the horizon.

You have filled the Two Lands with your

beauty like the sky, radiant with glaze. Inasmuch as you have been reborn as

the solar disk in the sky.

Here the underworld god Sokar is solarized, in a blending of the celestial and the underworldly, just as the two ways are one. To St. Hippolytus, who may have hailed from Egypt, is ascribed an Easter hymn of the early third century A.D., in which are the words:

The gates of heaven are opened. God has shown himself man,

And man has gone up a God.

Through whom the gates of the underworld are shattered,

And the Adamantine bars broken.

The people of the world below have risen from the dead, bringing good news (Migne 1862: 745; Hamman 1961: 32).

Here in the context of an Easter Mass, human time pales into insignificance and irrelevance to the believer, for the great event is totally present and now. So too with the ancient Egyptians, mummification and burial, seen as religious acts, implied a transcendence into the realm of divine time through association with Osiris and Re. That a mummy might eventually be destroyed by tomb robbers may have presented no greater problem to the religious Egyptian than the fact that the dead saints were actually still lying in their graves on the particular Easter Day when St. Hippolytus’s words were recited as an expression of Christian faith.

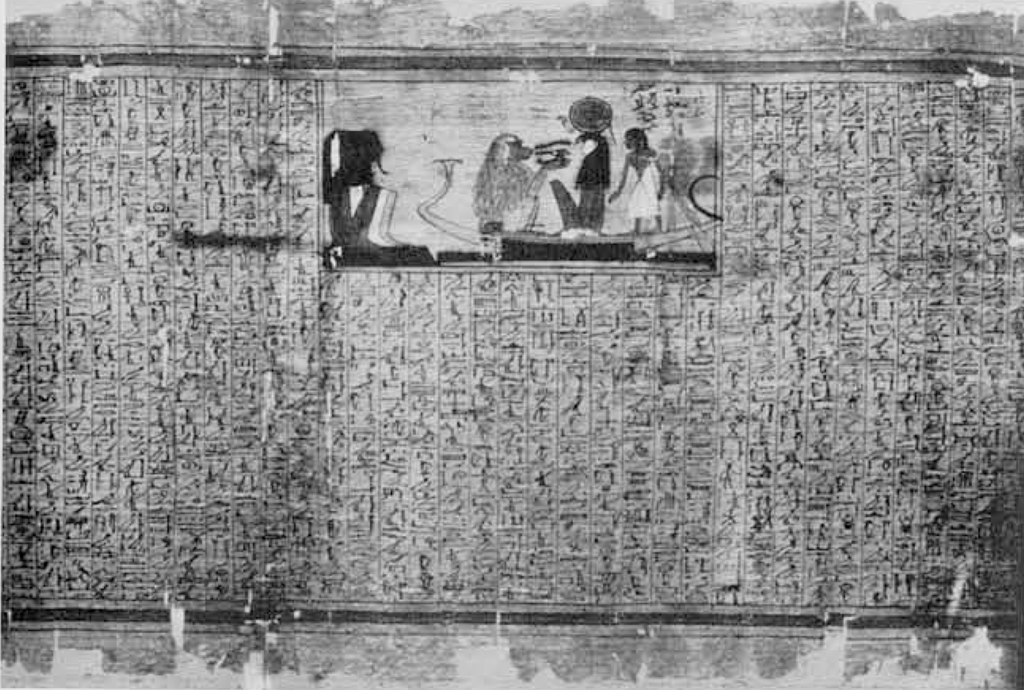

Not every aspect of the afterlife was entirely pleasant, and difficulties might be encountered in passing through the nether-world, whose gateways were guarded by fierce demons. Through magical spells the dead person sought to appease the demons, claiming knowledge of their names to gain access. Vignettes and texts in the Book of the Dead portray a judgment of the deceased, which actually comprises two episodes: one the weighing of the heart in a balance against the feather of Maat (truth) and the other the deceased’s recitation of the so-called Negative Confession—a series of denials before the netherworld tribunal that he had committed any one of a long list of sins. Having so boldly established his righteousness before the forty-two judges, the deceased was then admitted into the presence of Osiris, lord of the underworld. By depositing with the dead a copy of the judgment scene it would seem that the Egyptian was by magical means securing an automatic laissez-passer into the realm of Osiris. Such deception of the divine judges of the netherworld might seem most brazen. In fact, the Negative Confession is preceded by the words, “Purging [the deceased] of all sins he has committed.” The heart scarab, placed on the mummy’s chest, bore a text whose purpose was to prevent the heart, or conscience, from acting as an adverse witness in the tribunal. Scholars have seen in the Egyptians’ use of the Book of the Dead an unreconciled incompatibility between a magical approach and morality and piety. Yet the Book of the Dead was in use among even the highest officials.

Museum Object Number(s): E16218

In evaluating the judgment of the dead one must remember that by the time the deceased had reached the judgment hall, he had already undergone rites of purification and had attained a spiritual existence that involved identification with Osiris. In this respect the deceased shared in the triumphant vindication that had originally been accorded Osiris. If a perfect life were the sole criterion for gaining admission into paradise, then most Egyptians would obviously not have made it, since few led faultless lives. While the Egyptians, as we know from their wisdom literature, possessed a high standard of ethics and were not lacking in piety and morality, we must not confuse piety and morality with a strong sense of guilt, which was not a characteristic feature in Egyptian religion.

The division of the judgment into two espisodes is perhaps a reflection of the Two-Way motif. The psychostasy, or weighing of the heart against the feather of Maat, precedes the Negative Confession, and there is some evidence that it was originally associated with the sun-god. In Egypt the source of the ethical life was but a principle, Meat, that related to balanced and harmonious order throughout the created world. It applied to the workings of the cosmos, relationships within society, and an individual’s behavior. The sun-god Re fashioned Maat as his own daughter, and it was he that put Meat into men’s hearts enabling them to lead just lives. Thus Maat was a gift of god guiding man on the proper course, whereas man’s aberrations were the result of ignorance, witlessness, and disobedience. In a sense Re’s way was one of salvation as Maat, against which the heart was weighed, was a gift of the creator god.

The first phase of the judgment thus permitted the Egyptian to be confident that no incriminating wrongs would be adduced against him as he underwent the Negative Confession. It would appear that the heart scarab was meant to prevent the individual from becoming so overburdened with guilt consciousness that he could not boldly accept god’s graciousness that enabled him to participate in Osiris’s vindication and renewal. It was the absence of an overbearing sense of guilt that permitted the Egyptians to combine morality with ritual so effectively, and this combination provided the means for one’s salvation without a depressing sense of guilt.

One last question is, “Was mummification necessary to achieve a blessed afterlife?” or conversely, “Did the ritual of mummification automatically insure a blessed afterlife, even for the impious?” The motif of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) is first attested in Egypt in a story of the Roman period, where the riches of a haughty and richly provided man are given to the poor but upright individual buried only in a mat. In the much older Book of Amduat from the New Kingdom royal tombs a contrast does exist between the depiction of individuals who through drowning without a burial attain a blessed afterlife aided by divinities in achieving apotheosis and the depiction of eight deities “who denude the corpses and tear off the mummy bandages of the enemies, whose punishment is ordered in the netherworld.” For those who had failed to live in accord with Maat there was an Egyptian hell, depicted and described in the theological compositions treating the underworld. Here the parts of one’s being were never united but subjected to torture and fire as a prelude to complete extinction (Hornung 1968: 12-3).

In accordance with the Egyptian conception of two ways as not presenting an either-or proposition, one might conclude that the Egyptians did not make a sharp distinction between the emphasis on an ethical life and ritual burial. Both were advisable to achieve the blessed state.