Hutchinson, in his diary, part of Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, published by Thomas Bowdich in 1819, paints the following picture:

This week past Apokoo and several of the captains (chiefs) have been making an exhibition of their riches. This is generally done once in the life by those who are in favour with the King … It is done by making their gold into various articles of dress for show. Apokoo, who sent for me … showed me his varieties. weighing upwards of 800 bendas (slightly more than two ounces each) of the finest gold: among the articles, was a girdle two inches broad. Gold chains for the neck, arms, legs, &c ornaments for the ancles of all descriptions, consisting of manacles, with keys. bells, chairs, and padlocks.”

One hundred and fifty years later it is still possible to see in Ashanti country the paraphernalia of the chiefs.

In the modern Republic of Ghana the Ashanti Federation still functions and the chiefs or omanhene sit enstooled in their respective courts in and around the traditional capital, Kumasi. As in the past, each chief is elected and enstooled. inheriting with the office the royal paraphernalia that descends with the stool. Goldsmith guilds were commissioned by their royal patrons to supply ornaments and insignia. It is these that attest to the golden splendor of the Ashanti Kingdom.

How were these objects made? Bowdich himself described the process:

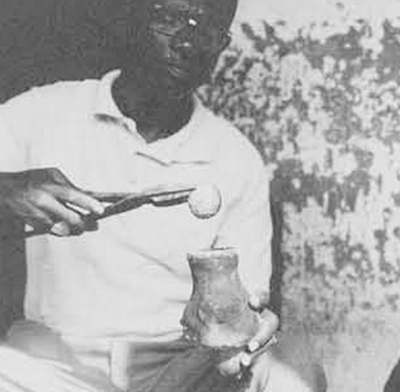

“Bees wax for making the model of the article wanted, is spun out on a smooth block of wood, by the side of a fire, on which stands a pot of water; a flat stick is dipped into this, with which the wax is made of a proper softness; it takes about a quarter of an hour to make enough for a ring. When the model is finished, it is enclosed in a composition of wet clay and charcoal, (which being closely pressed around it forms a mould.) dried in the sun, and having a small cup of the same materials attached to it, (to contain the gold for fusion,) communicating with the model by a small perforation. When the whole model is finished, and the gold carefully enclosed in the cup, it is put in a charcoal fire with the cup undermost. When the gold is supposed to be fused, the cup is turned uppermost. that it may run into the place of the melted wax: when cool the clay is broken. and if the article is not perfect it goes through the whole process again. To give the gold its proper colour, they put a layer of finely ground ochre all over it .. . and immerse it in boiling water mixed with the same substance and a little salt; after it has boiled half an hour, it is taken out and thoroughly cleansed from any clay that may adhere to it. Their bellows are imitations of ours, but the sheep skin they use being tied to the wood with leather thongs, the wind escapes through the crevices, therefore when much gold is on the fire they are obliged to use two or three pair at the same time. Their anvils are generally a large stone, or a piece of iron placed on the ground. Their stoves are built of swish (about three or four feet high) in a circular form. and are open about one fifth of the circumference; a hole is made through the closed part level with the ground. for the nozzle of the bellows.”

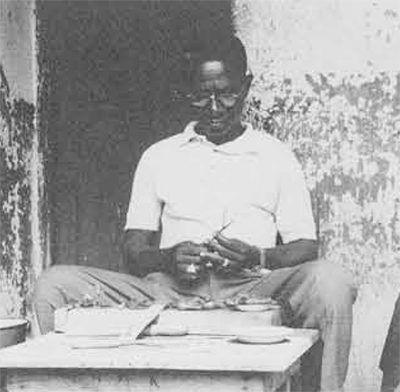

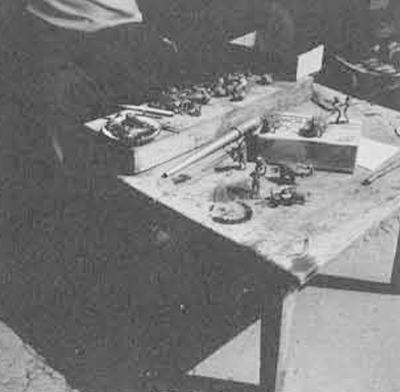

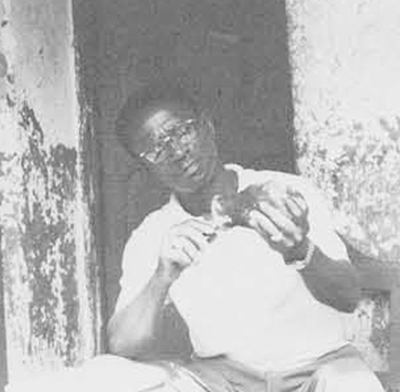

The goldsmiths still working in Kumasi carry on the same processes for making gold objects as well as goldweights. A carefully guarded trade is passed on from father to son.

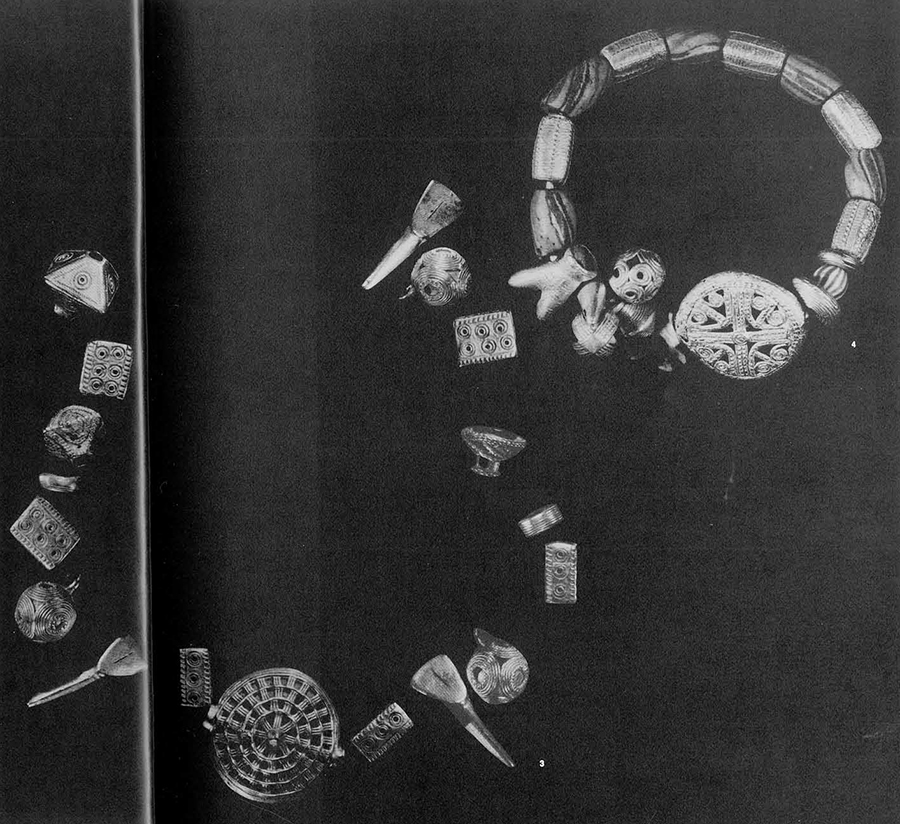

Through the kind agencies of the Medical Mission Sisters outside of Kokofu, the Museum was able to acquire directly from the son of a local goldsmith eighteen gold beads and amulets (70-18-1-18). The largest (shown in the center, diameter 11/4″) is a small soul-washer badge, worn on a white cord of pineapple-leaf fibers to ward off evil from the soul of the royal personage.

In addition, there are six rectangular “weight” beads decorated in typical Ashanti design (six fused double circles on each of the wide sides and three on the narrow with bands of hatching at the sides); three spheres of concentric wire circles looped for stringing; three human incisors perhaps commemorating prisoner trophies; two spacers; two pyramidal-shaped beads; and one shaped like a small earplug.

The beads were presented unstrung and may represent a goldsmith’s extra stock. Made in the 1930’s they certainly reflect the traditional forms that occur in the many royal treasures of the chiefs of the legendary Gold Coast.