The year 2000 marks both a month and a 50th anniversary for Gordion. In 1900 the German Koerte brothers conducted the very first excavations at the site; that work, while productive, lasted only a single season. Fifty years later, in 1950, Rodney S. Young undertook the excavations that initiated the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s long association with the site.

The years of Young’s directorship, down to his death in 1974, constituted a heroic age of particular his work spotlighted them during the 8th and early 7th centuries BC, when Gordion was clearly their capital and when they were at the acme of their military and political power under the celebrated King Midas.

Two remarkable archaeological phenomena combined to make that phase especially revealing. One level on the settlement mound dating to that period was largely swept by a disastrous fire which, while not claiming any human victims to our knowledge, dramatically locked in place evidence of the lives of the inhabitants. Furniture, looms. and storage vessels remained in situ, along with a great variety of other material, right down to a poker still lying across a hearth and grain still clinging to a grinding stone. Subsequent rebuilding operations sealed the burned level under a thick layer of clay that generally prevented later disturbances. It was left to Rodney Young to break the seal.

The other circumstance that makes the period so informative is that the tumuli of that era held a particular abundance of goods, none more so than the colossal “Midas Mound.” This is very likely the tomb of Midas himself. Young came to reject this identification in spite of having originated it, but restudy of the tomb’s chronology has strengthened the case for the old identity.

With the vivid evidence Young found for the Phrygians during the Age of Midas, it is hardly surprising that the culture of that time came to be widely perceived by archaeological scholars at Gordion and elsewhere as the defining stage of Phrygian culture.

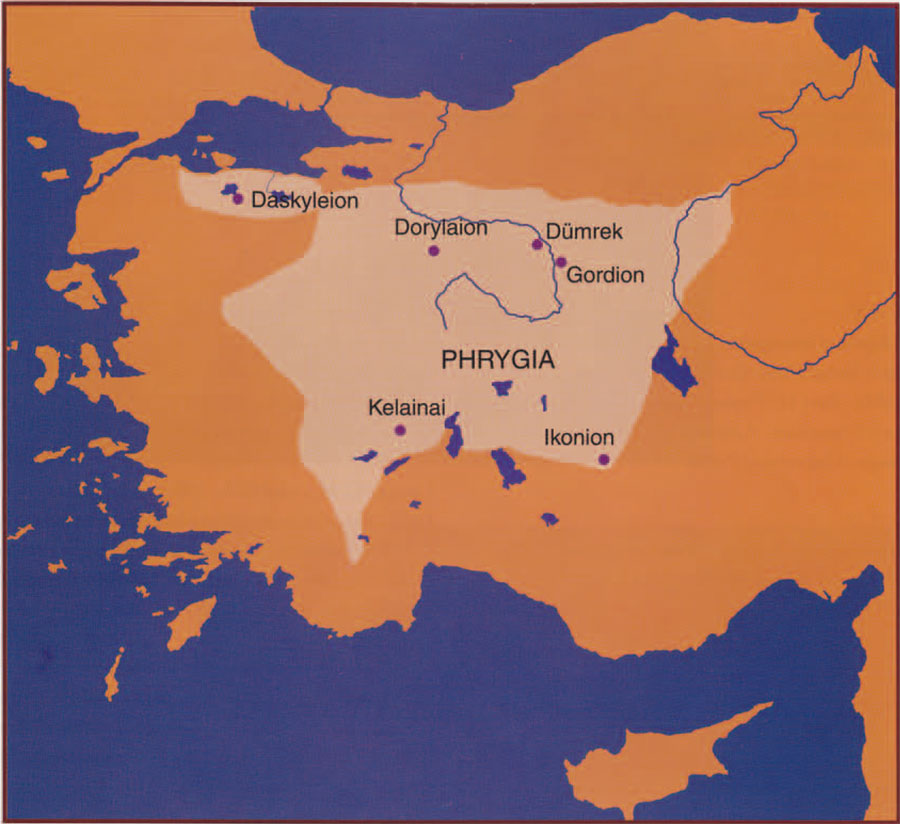

In the quarter century since Young’s death, our understanding of the Phrygians has continued to increase. Some of the recently attained knowledge has stemmed from discoveries beyond Gordion itself. In particular, new findspots of Phrygian inscriptions indicate that Phrygia was considerably larger than had been supposed, covering a broad expanse of central and western Anatolia (Fig. I). Some information has come from evidence provided both at Gordion and other Phrygian sites, notably, a new understanding of Phrygian material and artistic culture in the period following Midas’s time. This later culture, while undergoing changes, remained important and distinctive for several centuries. Progress has been made, too, in understanding Phrygian inscriptions, which have turned up in numbers not only at Gordion but at all Phrygian sites excavated to any significant degree. The society was a surprisingly literate one, especially in the 7th to 4th centuries BC.

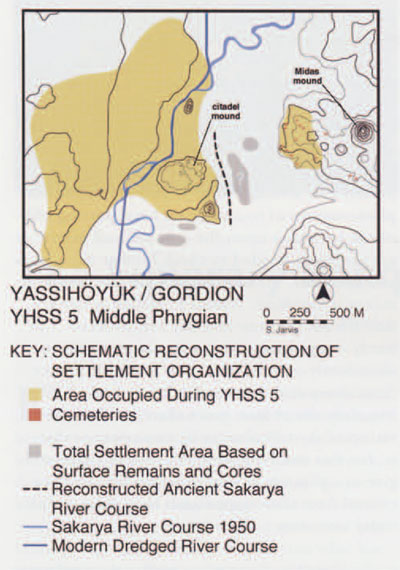

Other new information about Phrygian Gordion itself has been gained from renewed excavation at the site and the launching of surveys in its environs. Mary Voigt has directed the new fieldwork since its inception in 1988, while G. Kenneth Sams has served as the overall head of the Gordion project. Voigt’s work to date has revealed that Gordion was a much larger town than had been thought. The settlement mound was not the whole, or even most, of the habitation investigation. He explored over two dozen tumuli (burial mounds), cleared a large portion of the upper levels of the main settlement mound, and determined the overall periods of significant occupation, from late in the Early Bronze Age down to the Roman Imperial period, finding also some signs of a medieval presence.

Above all, he illuminated the centuries when the site was inhabited by the Phrygians, a people about which little was known archaeologically. In area but simply its elevated citadel; the rest of a much more extensive settlement stretched out well beyond it (Fig. 2). She has established that this was true of the site from at least the late 7th to the 4th century BC; awaiting clarification is whether it already had taken that form by the period of Midas in the 8th century BC.

The achievements of Rodney Young, however, remain permanent; his work is the basis on which current activities and study at Gordian and, often, other Phrygian sites build. It is fitting that the two articles that follow discuss work connected with a monument so closely associated with him, the towering Midas Mound.

Young and his team carefully gathered samples of the residues found in many of the pottery and bronze vessels from the tomb, but as Patrick McGovern points out in his article the results of the original analyses were disappointing. Aside from basic chemical findings, the conclusions noted “organic” and a possible “original presence of fatty matter” but nothing more specific. McGovern’s remarkable, detailed results are far more extensive and bring still more vividly to life the time of Midas at Gordion, adding striking particularities of food and drink.

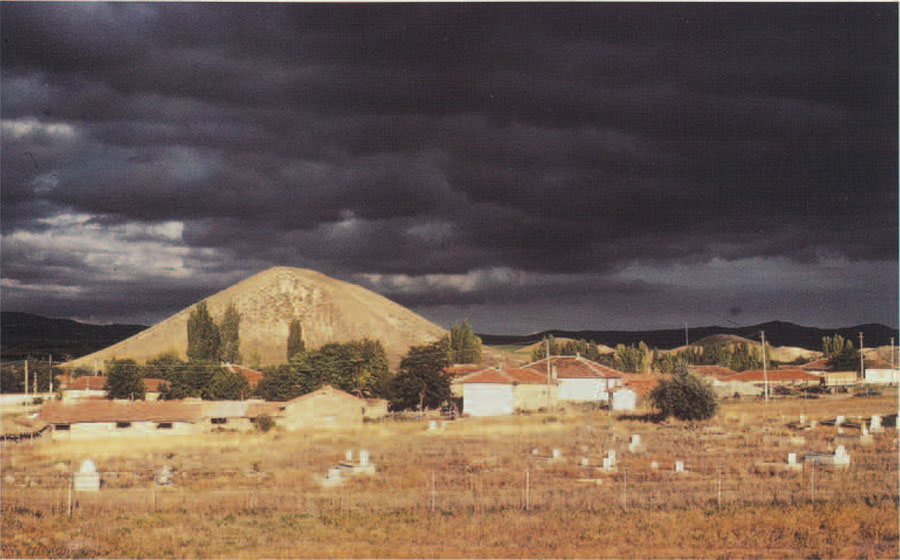

The Midas Mound today stands about 53 meters high, but it clearly rose still higher in antiquity. Erosion must have long affected it, for deep channels and worn-down contours are already conspicuous in a photograph the Koerte brothers took in 1900. The relatively recent presence of a village (Fig. 3) and the still newer phenomenon of tourism have been putting additional pressures upon the mound, and measures are obviously needed to check further deterioration of this, the most striking of the monuments at Gordion. Naomi F. Miller in her article details the remedies she has initiated. The hardy steppe vegetation each year grows more abundantly on its slopes, now that disturbance from sheep and humans has been checked. She has made the project more than just the conservation of the tumulus itself, important as that is, for this small but unique protected zone will give us a glimpse of a more natural state of the central Anatolian steppelands than most people today have seen.