Doña Norma makes her way through the undergrowth along an overgrown path while every so often making a quick swipe with her machete to clear encroaching vegetation. We are less than twenty meters from doña Norma’s house, but her yard quickly gives way to the forest. To the unknowing eye, it is a dense swath of green Amazonian jungle. However, doña Norma was able locate, identify, and explain the properties of each plant rooted in the small garden that extends beyond her home in the rural Amazonian village of El Chino.

Home gardens are used throughout the world as staples for food production and vary dramatically in size, species richness, and composition. Scholars are increasingly acknowledging the significance of home gardens for species conservation and as reservoirs of cultural knowledge. In the rural Peruvian Amazon, home gardens (known locally as huertos) complement horticultural fields (chacras) and not only supplement diet, but also play a significant role in traditional healing practices. This article presents findings from a preliminary study of diversity in home garden composition in the Tahuayo region of the Peruvian Amazon and focuses on the significance of medicinal plants as central to garden composition. The findings indicate an importance of home gardens beyond their role as contributors to diet and nutrition.

Field Site(s)

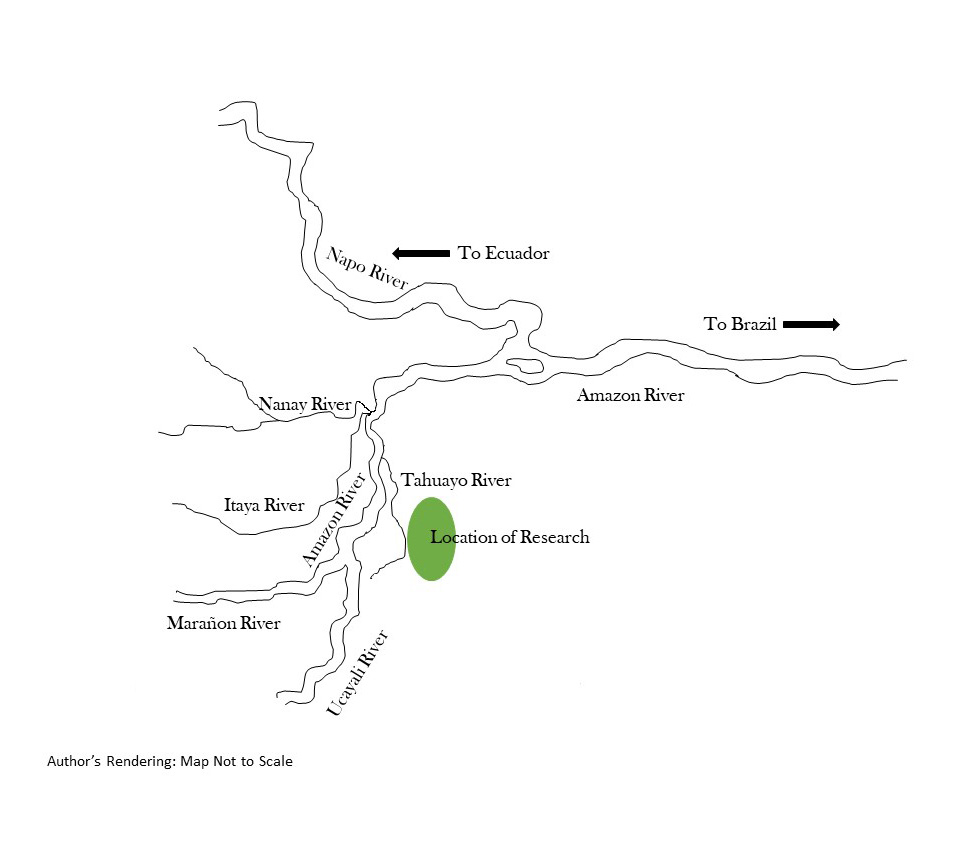

Research was carried out in Peru’s northeast Loreto district in three communities associated with the Área de Conservación Regional Comunal Tamshiyacu—Tahuayo (ACRCTT). The ACRCTT is located between the Tamshiyacu and Tahuayo Rivers and was organized in the 1980s with formal establishment occurring in 1991. The ACRCTT encompasses over one million acres of protected forest that is managed by ten communities. This study took place amongst three of the northeasternmost communities associated with the ACRCTT. The study sites reflect the diversity of Amazonian communities as they vary in size, ethnic make-up, and remoteness.

El Chino is the largest of the three communities of study with a population of approximately two hundred individuals. Residents of El Chino partake in numerous economic activities including fishing, horticulture, craft production, and tourism. While all three communities are rural and economically disadvantaged, El Chino exhibits the greatest level of acculturation and relative affluence of the three communities of study.

San Pedro is located approximately two hours from El Chino along the Río Blanco River. It is a smaller community with approximately forty residents spread across seven households. Despite the distance, San Pedro and El Chino are linked by kinship ties extending between the two communities, a feature that is not unique to these communities, but is characteristic of the numerous communities of the Tahuayo region.

Jerusalén is an Indigenous Achuar community located along the Tahuayo River approximately five hours upriver from El Chino. At the time of this study, the village consisted of thirteen households and approximately fifty residents, the majority of whom are members of an extended family related to the village headman and shaman who first settled in the area in the 1960s while working as an indentured laborer.

Even as the communities vary demographically, all are ribereño communities, and kinship and cultural connection exists amongst the communities. The term ribereño refers to rural peasants who live along navigable waterways in the Peruvian Amazon. Beyond this, the term carries ethnic connotations as it refers to mixed ancestry of not only European and Indigenous, but of multiple Indigenous ethnicities. This is a typical feature of all three study communities where residents of Indigenous Achuar, Aguaruna, Shuar, Yagua, and Kichwa ancestry live together, and where the local dialect incorporates numerous words of the various languages.

Methodology

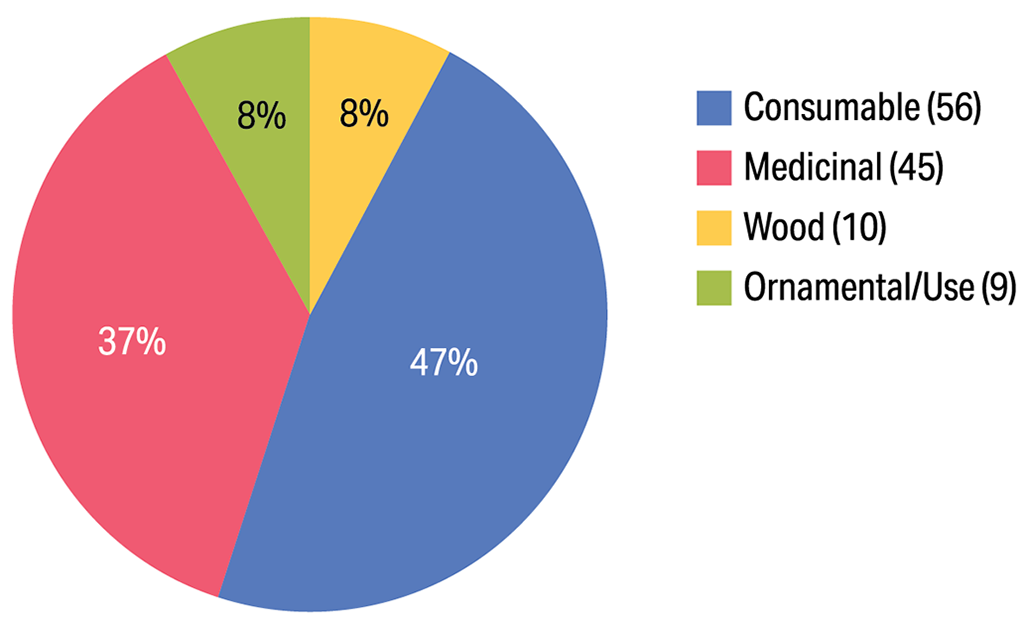

The aim of this project was to understand and document diversity (species richness) of home gardens in the three communities of study. The first step in the research process was to establish a system of categorization used in plant identification. Following the work of Cuanalo de la Cerda and Guerra Mukul (2008), an approach was adopted that organized plants into four categories including consumable plants, medicinal plants, wood, and ornamental and other uses. This provided a straightforward way to document plant use and served as a framework for comparing garden composition within and across communities. Research occurred in July and August 2014 with a follow-up visit during the same months in 2015 and consisted of engaging local participants in conversations about their home gardens and the diversity of plants present. Heads of household, either male or female, were asked to provide a brief tour of the garden and identify the plants and their use values. The local name for each plant was recorded as well as the category of use identified by the consultant. Additional information was recorded including specific use of the plant beyond the general categorical designation.

Four questions guided the research process: (1) Is there a correlation between relative remoteness of community and home garden diversity? (2) What factors beyond relative remoteness can account for variations in home garden diversity across communities? (3) What is the single most important factor that contributes to home garden diversity? (4) What is the overall distribution of plant species utilized in home gardens of the Tahuayo?

Working in home gardens can provide unanticipated outcomes and challenges. An initial goal of the project was to measure home garden size and to see if garden size had any correlation to its plant diversity. It became evident early on that measuring garden size would be extremely challenging due to the layout of Amazonian home gardens. While some gardens are organized in a discrete manner with fairly clear boundaries, the majority of home gardens documented lacked what I would classify as definitive boundaries. In most cases, gardens simply gave way to the forest and as one walked greater distance away from the home, garden plants were further apart and less easy to distinguish from the forest plants. Two such examples are the gardens of doña Norma and don Marcos. Each garden begins near the home in what is a visible space of cultivated plants including organization of multiple small plots as well as plants in containers. The space is distinct from the forest and has a notable association with the home. However, as one walks further from the home, garden plants become increasingly intermingled with the forest. In the case of don Marcos, his garden extends into his hog enclosure where a variety of fruit-bearing trees such as plantain, lime, and grapefruit form a small orchard that extends beyond the boundaries of the hog enclosure and into the nearby forest.

A second challenge was encountered during the identification process. While the focus was on understanding variation in home gardens and documenting local names for plants and associated local cultural knowledge, there was also an attempt to establish a correlation between local names and their names within the Linnean classification system. I was first and foremost concerned with local identification and then worked from that to identify the family, genus, and species. Working from local names and photos taken of all plants, I relied on multiple sources and systems of support to identify scientific names. These included a heavy reliance on native naturalist guides with a deep ethnobotanical knowledge, and cross-referencing findings with published literature including the authoritative Amazonian Ethnobotanical Dictionary. In some cases, this manner of identification involved working late into the evening while diving deep into the literature trying to identify the scientific classification for names of plants provided by local consultants. It also involved more than one case of confusion, as local names for plants can vary depending upon Indigenous language of origin. Moreover, the local dialect of Spanish reflects the ethnic complexity of the region and the numerous Indigenous influences that combine to form local ribereño culture. In such cases, it was necessary to cross-reference names with consultants to address any confusion and to appropriately identify the plants in question.

Results

One hundred and twenty species were identified in the 33 gardens surveyed for this study. One hundred and six plant species were identified in the gardens of El Chino, 43 species were identified in San Pedro, and 39 species were identified in Jerusalén.

Despite this great diversity, only 15 species were found in all three communities. The most common plants in each community were found to be high yield fruit producing plants including Mauritia flexuosa, a palm known locally as aguaje, Eugenia stipitate, known locally as guayaba brasilera, Musa paradisiaca or plátano, and Cocos nucifera a coconut palm known locally as coco.

Plants Identified Per Community

Perhaps more revealing than the distribution across communities is the distribution of plants as related to established categories that define this study. The overwhelming majority of species in all three communities fell into the categories of fruits and medicinal plants. In El Chino, 91 of the 106 species were identified as consumable (49) or medicinal (42). In San Pedro, 38 of the 43 species were identified as consumable (23) or medicinal (15). And in Jerusalén, 32 of the 39 species were identified as consumable (23) or medicinal (9).

“My parents were shaman. My father was mestizo (of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry), but his ancestry was Aguaruna. He came from the upper Amazon, during the war (of 1941). My mother was from Pastaza, upper Amazon, Ecuador. I learned vegetable medicine (traditional medicine) from them when I was fourteen years old.”

Many plants identified by the owners of home gardens fit into the primary category of consumable while also having medicinal uses. Some examples include cacho/cashu (Anacardium occidentale), used in treatments for diarrhea and to kill bot-fly larvae, pandisho (Artocarpus altilis), an anodyne for treatment of burns, and huingo (Crescentia cujeta), used to treat asthma. Of the 56 plants categorized as consumable, 29 also have medicinal properties. When added to the plants originally categorized as medicinal, the total number of plants with medicinal qualities and uses increases from 45 to 74. In total, 61 percent of the plants identified have medicinal properties and uses. It is beyond the scope of this article to detail the specific uses of each medicinal plant. However, a few plants merit special mention.

The medicinal plants most common to the home gardens of the Tahuayo include achira (Canna indica), yerba Luisa (Cymbopogon citratus), pampa oregano (Lippia alba), malva (Malachra alceifolia), and ajo sacha/sacha ajo (Mansoa alliacea). In the Tahuayo, yerba Luisa is used to treat stomach ailments, and sacha ajo is commonly used by native healers in cleansing rituals.

While these plants were present in 20 percent to 40 percent of the gardens surveyed, 29 medicinal plants occurred in two or fewer gardens. Some of the more unique plants encountered in the home gardens of the Tahuayo include toé (Brugmansia aurea), sangre de grado or sangre de drago (Croton lechleri), hoja del aire (Kalanchoe pinnata), and paico (Chenopodium ambrosioides). Like the more commonly found plants, most of these less encountered species have medicinal properties that can be used to treat routine injuries and illnesses. For example, the resin produced by sangre de grado is used to treat wounds including minor cuts and burns, and various ointments and salves made of sangre de grado are sold commercially in the regional capital of Iquitos. The crushed leaves of oja del aire can be used to reduce fever, and paico is used to treat stomach related ailments. Toé is unique amongst these as it is a powerful hallucinogenic used for divination and healing.

Plants by Category (N=120)

Traditional healing is commonplace in the Tahuayo and most people have some knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants. However, depth and breadth of knowledge are associated with a select few individuals who practice traditional healing through shamanic and non-shamanic methods. Shamanic practices combine the use of medicinal plants and interaction with the supernatural to heal as well as to ward off the presence of malevolent spirits. Healing focusing strictly on use of medicinal plants and without any supernatural component, is practiced by curanderos, or what are often referred to in English as herbalists. In both cases, knowledge of medicinal plants is passed down generation to generation and skilled practitioners tend to be community elders.

One such healer is don Adolfo, an elderly shaman of Indigenous ancestry who worked as a medical assistant in the city of Iquitos prior to moving to the Tahuayo region to be close to his wife’s family. I have known Adolfo for many years, and he is always willing and eager to share stories with me and provide insights about life in the Tahuayo. He keeps busy working for a tourism lodge in the area and is often away from his home in El Chino. This is common for many people living in the rural Amazon as opportunities for work frequently lead to extended absences from their homes. On an occasion when Adolfo was in the village, I was able to speak with him about his life. We met at one of the small stores in El Chino. The store—contained within the front room of a home—also serves as a space for social interaction, and it is common for people to meet there throughout the day to enjoy a beverage, a game of cards, and conversation.

Don Adolfo explained the strict regimen of diet and instruction that increased with intensity over the course of twelve years of gaining shamanic knowledge. He reflected how during his youth there was no thought of being educated for a profession. Instead, he learned what his parents knew. This included gaining knowledge and experience as a shaman. Don Adolfo lamented the fact that children now have less interest in learning about shamanism and traditional healing practices. There is a greater interest in sports and parties. Moreover, formal education, the kind that leads to a profession, is more common now than it was even a few decades ago. Such changes lead to economic opportunity, yet result in diminished focus on traditional healing practices in the communities of the Tahuayo.

Doña Romelia is an herbalist. Her home garden is unique amongst the home gardens of the Tahuayo as it is comprised of an expansive array of elevated beds and containers that complement her terrestrial garden while being an adaptation to the seasonal flooding that requires homes to be on stilts above the ground. Doña Romelia’s garden was the most diverse encountered during this study. It included 48 species of plants, 28 of which were medicinal. In addition, 8 of the 18 plants designated as fruits also contain medicinal properties. Most of the plants grown by doña Romelia serve to treat common illnesses included stomach ailments, diarrhea, treatment of insect bites, burns, and cuts, and to alleviate pain and nausea. Doña Romelia’s knowledge of medicinal plants, like that of don Adolfo, was passed down through family. And her knowledge is used for the benefit of village residents.

Access to healers specializing in medicinal plants is a valuable resource in the Tahuayo. For communities including El Chino, San Pedro, and Jerusalén, access to western medicine previously required travel to either the town of Tamshiyacu or the city of Iquitos. In recent years, a small clinic has been established in the village of La Esperanza. It is only an hour or so by motorized boat from El Chino and serves as the medical hub for the communities of the Tahuayo. However, not all residents have easy access to transportation to the clinic, thus traditional healing practices remain a viable alternative for many residents of the communities of study. As this study indicates, home gardens, knowledge of medicinal plants, and traditional healing practices are noteworthy aspects of culture in the Tahuayo.

Conclusions

While home gardens are often considered for their contributions to daily nutrition, they also represent significant resevoirs of traditional knowledge related to healing. The home gardens of the Tahuayo reflect the prominence of plant-based healing practices and local knowledge of medicinal as well as non-medicinal plants and their uses. Within these gardens, it is notable that high diversity corresponds to utilization of plants for healing purposes, as the most diverse gardens also contain the greatest number of plants with medicinal properties. Thus, the single most important factor in home garden diversity is the production and use of medicinal plants. In the Tahuayo, like many rural regions of the Peruvian Amazon, it is increasingly common for younger generations to leave their natal communities to seek out education and employment in urban centers including Iquitos and Lima. As youth and young adults leave, and elder generations pass on, knowledge is lost. For specialists with expertise of medicinal plants, home gardens represent a physical manifestation of generations of healing knowledge. Documenting home gardens provides more than mere understanding of plant distribution and use. Ethnographic research on home gardens provides insight into culturally specific ways of knowing while also creating a record so knowledge is maintained for future generations.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Nelly Pinedo Alvarado and Weny Pinedo Flores for their support during this project. My sincerest appreciation to the people of the Tahuayo. Thank you to Amazonia Expeditions for logistical support and the University of Southern Indiana Foundation for funding this project.

Daniel Bauer holds a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Southern Illinois University–Carbondale and is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Southern Indiana. He has ongoing research projects in Amazonian Peru and Coastal Ecuador and is author of Identity, Development, and the Politics of the Past: An Ethnography of Continuity and Change in a Coastal Ecuadorian Community (University Press of Colorado, 2018).