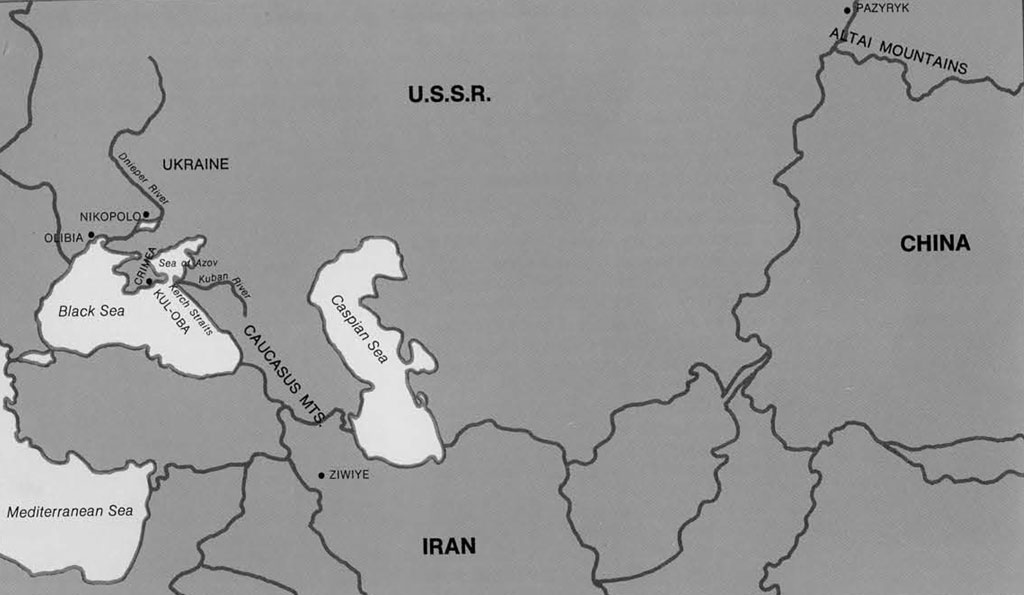

The Greek historian Herodotus (490/480-425 B.C.], in his History of the Persian Wars, included an excursus on the ethnography of the Scythians and other nomadic groups with whom the Greeks were familiar. Some of the information which Herodotus provided about these nomadic peoples he apparently had gathered during his own trip to the Black Sea region, which took him as far east as the city of Olbia and the Dneiper River (called the Borysthenes by the Greeks]. Much information which he collected must have come secondhand from the Black Sea Greeks who traded with the Scythians, who provided the Greeks with policemen, fish, and wheat, among other things. Other information was apparently hearsay, and reached the Greek world along with such goods as silk, traded from Eastern Asia.

How accurate was this information recorded by Herodotus?

It is possible to test the validity of his ethnographic information against archaeological evidence from the Black Sea steppe eastward to China.

But before doing so we must make two assumptions. First, as we know from archaeological evidence that the cultures of the people of the Eurasian steppe were relatively homogeneous during the middle centuries of the first millennium B.C., we will use evidence from the whole steppe area rather than just the Pontic (i.e., Black Sea) region to substantiate the observations of Herodotus about the Black Sea Scythians.

Secondly, Herodotus describes a variety of tribes, naming them and placing them in a geographical framework. But we cannot correlate the names given by Herodotus with specific sites or groups of artifacts, so we will treat the nomads Herodotus names as essentially a homogeneous culture, although there must have been ethno-linguistic variations among them.

The validity of these assumptions is supported by the investigation, as we hope to show below.

The Archaeological Evidence

The Greek historian Herodotus (490/480-425 B.C.], in his History of the Persian Wars, included an excursus on the ethnography of the Scythians and other nomadic groups with whom the Greeks were familiar. Some of the information which Herodotus provided about these nomadic peoples he apparently had gathered during his own trip to the Black Sea region, which took him as far east as the city of Olbia and the Dneiper River (called the Borysthenes by the Greeks]. Much information which he collected must have come secondhand from the Black Sea Greeks who traded with the Scythians, who provided the Greeks with policemen, fish, and wheat, among other things. Other information was apparently hearsay, and reached the Greek world along with such goods as silk, traded from Eastern Asia.

How accurate was this information recorded by Herodotus?

It is possible to test the validity of his ethnographic information against archaeological evidence from the Black Sea steppe eastward to China.

But before doing so we must make two assumptions. First, as we know from archaeological evidence that the cultures of the people of the Eurasian steppe were relatively homogeneous during the middle centuries of the first millennium B.C., we will use evidence from the whole steppe area rather than just the Pontic (i.e., Black Sea) region to substantiate the observations of Herodotus about the Black Sea Scythians.

Secondly, Herodotus describes a variety of tribes, naming them and placing them in a geographical framework. But we cannot correlate the names given by Herodotus with specific sites or groups of artifacts, so we will treat the nomads Herodotus names as essentially a homogeneous culture, although there must have been ethno-linguistic variations among them.

The validity of these assumptions is supported by the investigation, as we hope to show below.

Archaeological evidence for this investigation comes principally from two regions. The first is the Black Sea region, where the Greeks established settlements from which to trade among local peoples with whom they came into direct contact. The artifacts which we will consider from this region come principally from burials of the rich leaders of the Scythians and other tribes, and date to the 7th through the 4th century B.C. These burial mounds are concentrated in the lower Dneiper River area, and on either side of the Kerch Straits (between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov), in the Caucasus Mountains (mostly along the Kuban River] and in the Crimea. In these burials were found objects made by the nomads themselves, as well as many objects made for the Scythians, by Greek and, in earlier periods, by Near Eastern craftsmen. The objects made by non-nomadic craftsmen were probably traded to nomads for foodstuffs and other goods.

The second region rich in pertinent archaeological evidence is the Altai Mountains. The burials in the Altai MountainsPazyryk and other sites—contained objects of special interest, which, under most conditions, are lost to archaeologists. Shortly after the burials were completed, they were broken into by thieves, as the rich burials in the Black Sea region often were too. When the graves were robbed, water from the surface entered the underground burial chambers which had been covered with mounds of earth and stones. This water froze in the cold climate of the high mountains and remained permanently frozen due to the insulation of the mound above. Thus, wood, leather, felt, bodies, and other organic substances buried at Pazyryk in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. were still quite well preserved when Russian archaeologists excavated them in the 1920’s and 1940’s.

The method traditionally used by Minns and other scholars for testing the accuracy of Herodotus’ reports has been to read the sections where he describes the Scythians and other nomadic groups (primarily Book 4, chapters 1440] and compare his descriptions with the archaeological data from Eurasia during the 7th through the 4th century B.C. That is the method we also used.

We cannot include here all of the details Herodotus describes which are substantiated by the archaeological evidence. Instead, we will examine a few passages and will try to define the limits of Herodotus’ accuracy and usefulness for ethnographic purposes. The passage will be quoted, then followed by the relevant archaeological evidence.

Nomadic Scythians

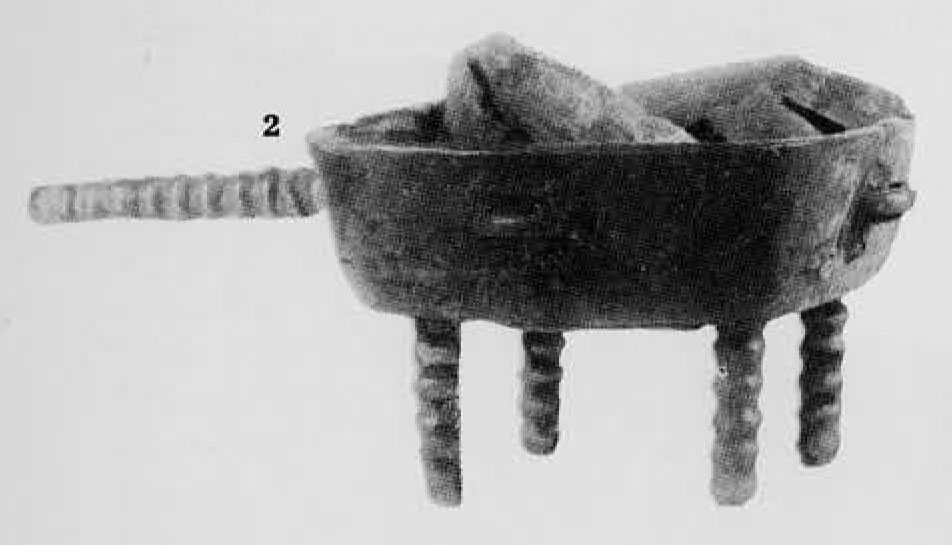

The first passage we will consider is from Book IV, chapter 46: “Having neither cities nor forts, and carrying their dwellings with them wherever they go: accustomed, moreover, one and all of them, to shoot from horseback: and living not by husbandry but on their cattle, their waggons the only houses that they possess, how can they fail of being unconquerable, and unassailable even?” Models of covered wagons have been found in the Black Sea region. Also, many objects designed for portable living have been found at Pazyryk, including wooden vessels and leather flasks, in addition to the more fragile ceramic containers, and small tables with legs that are easily removable for convenient transport.

Representations of Scythians shooting bows from horseback are illustrated on objects from Scythian tombs.

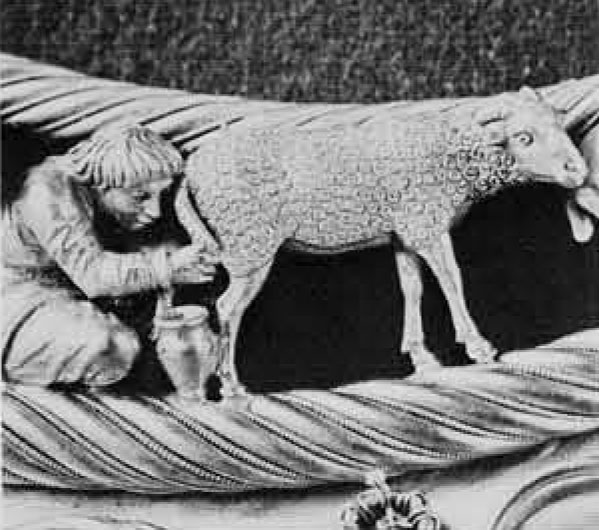

Archaeological evidence for their dependence on livestock and horses includes many representations of Scythians with livestock, including a necklace found recently by the Russians in a rich burial in the Ukraine.

However, traces of settlements have been found in recent years in the lower Dneiper region, and it has been suggested that these people were nomadic only in the summer, returning to the same winter quarters in successive years. Similar hypotheses have been put forth about those living in the Altai. But is it likely that their economic base was their flocks, and that the grain traded to the Greeks was grown by local agrarian people whom the Scythians controlled by actual or threatened force of arms? So Herodotus was generally correct in this statement, but probably exaggerated the non-sedentary nature of their lifestyle.

Arms and Armor

As a further test of Herodotus’ accuracy, we will examine the statement of Book I, chapter 215: “In their dress and mode of living the Massagetae resemble the Scythians. They fight both on horseback and on foot, neither method is strange to them: they use bows and lances, but their favourite weapon is the battle-axe. Their arms are all either of gold or bronze. For their spearpoints, and arrowheads, and for their battle-axes, they make use of bronze; for head-gear, belts, and girdles, of gold. So too with the caparison of their horses, they give them breastplates of bronze, but employ gold about the reins, the bit, and the cheek-plates. They use neither iron nor silver, having none in their country; but they have bronze and gold in abundance.”

“In their dress and mode of living the Massagetae resemble the Scythians.” Herodotus himself considers in this statement the strong similarity of two nomadic groups which were widely separated geographically, just as we have. He places the Massagetae (Book I, chapter 204) on a “vast plain” to the east of the Caspian Sea. The Scythians lived in the region just north of the Black Sea (Book IV, chapters 17-20, 48-57).

“They fight both on horseback and on foot, neither method is strange to them.” The evidence to support this statement includes the decoration on a Greek-made gold comb from a 4th century Scythian tomb on the Dneiper which shows a group of three Scythians in combat. One is mounted on horseback, and the other two are on foot, one apparently because his horse was slain, but the other is represented without a mount.

“They use bows and lances, but their favourite weapon is the battle-axe.” In this same scene on the comb we see the mounted figure fighting with a lance, and bows and arrows suspended at the left sides of the mounted and bareheaded figures. (The special case which held both the Scythian compound bow and the arrows is called a gorytus.)

Lances and bows can also be seen held by figures on a gold vessel from the Kul-Oba tomb on the Kerch peninsula. An elaborately decorated, gold-covered, iron battle-axe has been found in a Scythian tomb in the Caucasus, and the Scythians are represented on metalwork using battle-axes. Another form of Scythian battle-axe, in this instance made of iron and silver, is shown here.

“Their arms are all either of gold or bronze. For their spearpoints, and arrowheads, and for their battle-axes, they make use of bronze.” In the above paragraph are enumerated many gold-covered weapons. Scythians also used daggers and short swords with gold-covered sheaths and handles. Bronze spear-points, arrowheads, and battle-axes have been found in abundance.

Other arms included shields; a shield from Pazyryk made of parallel staves bound together with leather closely resembles the shields held by the figures on the Solokha comb. This fact supports our original assumption that we could use Herodotus’ descriptions of specific nomadic groups to give us an overall view of the Eurasian nomadic way of life in the middle of the first millennium B.C.

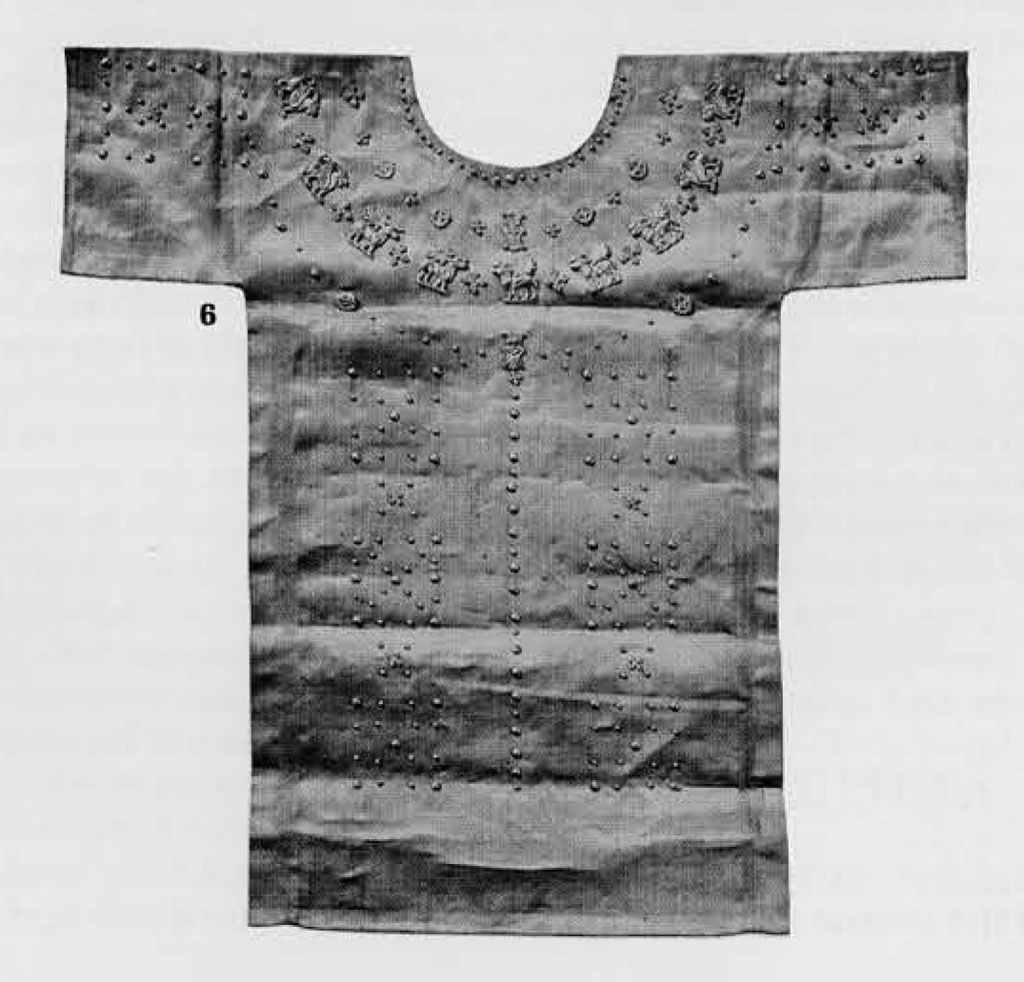

“For head-gear, belts, and girdles, of gold.” Scythian helmets of both bronze and gold exist. Part of a wide gold belt decorated with Scythian motifs, found in Iran, is illustrated here. The nomads wore gold elsewhere on their persons, especially in the form of small gold plaques, such as those applied to a shirt found in the Caucasus.

“So too with the caparison of their horses, they give them breastplates of bronze, but employ gold about the reins, the bit, and the cheek-plates.” Horse trappings have been found in the Pontic region and the Altai, many of which were of bronze, occasionally gilded. Gold cheek-pieces and frontlets have also been excavated, as well as horn and bone bridle fittings. In the Altai, wooden bridle pieces covered with gold leaf were excavated.

“They use neither iron nor silver, having none in their country; but they have bronze and gold in abundance.” It is indeed true that gold was plentiful in the Altai, and copper is found in the Caucasus. We can also see, however, from the axe illustrated above, that the Scythians used iron and silver as well as bronze and gold, although they were apparently less common. With the exception of the statement about the use of silver and iron, however, Herodotus recorded information which was accurate as far as it went; however, additional materials of fabrication were used in all the categories Herodotus listed. In this passage, Herodotus seems to generalize from reports and/or observations which were not entirely representative of actual practices.

Museum Object Number(s): 53-31-2A / 53-31-2B / 53-31-2C

Burial Practices

In Book IV, chapter 71, Herodotus describes the burial customs of the Royal Scythians: “The tombs of their kings are in the land of the Gerrhi, who dwell at the point where the Borysthenes is first navigable. Here, when the king dies, they dig a grave, which is square in shape, and of great size. When it is ready, they take the king’s corpse, and having opened the belly, and cleaned out the inside, fill the cavity with a preparation of chopped cypress, frankincense, parsley-seed, and anise-seed, after which they sew up the opening, enclose the body in wax, and placing it on a waggon, carry it about through all the different tribes … the body of the dead king is laid in a grave prepared for it, stretched upon a mattress; spears are fixed in the ground on either side of the corpse, and beams stretched across above it to form a roof, which is covered with a thatching of twigs. In the open space around the body of the king they bury one of his concubines, first killing her by strangling, and also his cup-bearer, his cook, his groom, his lackey, his messenger, some of his horses, firstlings of all his other possessions, and some golden cups; for they use neither silver or bronze. After this they set to work, and raise a vast mound above the grave, all of them vying with each other and seeking to make it as tall as possible.”

In this description all details can be substantiated except Herodotus’ insistence on the exclusive use of gold vessels. The river Borysthenes is the Dneiper, and there are many rich burials grouped together in the region around Nikopol. Many of the burial pits are square, although some are round, and they are very large. Embalmed corpses were excavated at Pazyryk, including the woman from Tomb 5, where the stitches closing the body are clearly visible. Wagons have been preserved in tombs in Pazyryk and fragmentary remains come from tombs in the Black Sea area. In the section of the Pazyryk tomb on page 17, the wooden lining of the grave pit is visible.

In another tomb in the Kuban River basin were found the skeletons of 360 horses, and the burial was not completely excavated. The mound which was put up over the tombs can be illustrated here by the Pazyryk burial.

In discussing a burial ritual, Herodotus says (Book IV, chapters 73 and 75): “To wash, they make a booth by fixing in the ground three sticks inclined towards one another, and stretching around them woolen felts, which they arrange so as to fit as close as possible: inside the booth a dish is placed upon the ground, into which they put a number of red-hot stones and then add some hemp-seed … immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy.”

Here, his information about purpose is a bit garbled, since he obviously has bathing confused with an intoxication ritual. However, he is accurate about the effect of burning hemp and the associated paraphernalia; one of the Pazyryk tombs contained a set of poles, a bronze container filled with stones and hemp seeds, and a cloth covering.

Eastern Peoples

Herodotus becomes vaguer, but remains useful, as he tries to describe the people far to the east of the Black Sea. In Book IV, chapter 23, we find the following description: (There are) “people who dwell at the foot of lofty mountains, who are said to be all—both men and women—bald from their birth, to have flat noses and very long chins…. Each of them dwells under a tree, and they cover the tree in winter with a cloth of thick white felt. They are called Agrippaeans.”

Clearly these “bald” people were Mongoloids, who would have looked relatively hairless to the Greeks. The felt covering the tree would have been their tents, such as were copied in the interior of Pazyryk burial chambers, which were lined with felt hangings. Some of the people buried at Pazyryk were Mongoloid; perhaps this passage refers to a people who lived in the Altai Mountains.

In this brief paper it is not practical to present the comparative archaeological material for each chapter of Herodotus’ description of the nomads. The examples given are typical. In summary, we can see that Herodotus gives relatively accurate descriptions of the way of life of the nomads who were in fairly close contact with the Greeks, as, for example, in his description of the burial process. But he is considerably more vague about details of tribes far away, where the evidence he had was hearsay and passed through many hands, as in his discussion of the Agrippaeans. He does, however, have a tendency to exaggerate, or to generalize from specific or unique observations. Nevertheless, from a comparison with currently available archaeological evidence, it is clear that Herodotus as an ethnographer was more often right than wrong.

We can of course evaluate directly only those of his descriptions which record artifacts which can be recovered by archaeologists. He gives other kinds of ethno-linguistic information such as religious rituals and names of gods, methods of warfare, social structures, trade routes, and language groups. Although it is impossible to verify, it is probably safe to assume that Herodotus is as accurate in recording these intangible cultural phenomena as he is in recording artifacts, and that the information he offers is reasonably accurate in many details. We must of course be exceedingly careful in the use of such ethno-linguistic information, since it remains unsupported. However, the fact that Herodotus provides us with information which can not be recovered by archaeological means, in addition to concrete details like those discussed above, makes his writings especially useful. Certainly, the work of Herodotus remains invaluable today.

Conclusion

In this brief paper it is not practical to present the comparative archaeological material for each chapter of Herodotus’ description of the nomads. The examples given are typical. In summary, we can see that Herodotus gives relatively accurate descriptions of the way of life of the nomads who were in fairly close contact with the Greeks, as, for example, in his description of the burial process. But he is considerably more vague about details of tribes far away, where the evidence he had was hearsay and passed through many hands, as in his discussion of the Agrippaeans. He does, however, have a tendency to exaggerate, or to generalize from specific or unique observations. Nevertheless, from a comparison with currently available archaeological evidence, it is clear that Herodotus as an ethnographer was more often right than wrong.

We can of course evaluate directly only those of his descriptions which record artifacts which can be recovered by archaeologists. He gives other kinds of ethno-linguistic information such as religious rituals and names of gods, methods of warfare, social structures, trade routes, and language groups. Although it is impossible to verify, it is probably safe to assume that Herodotus is as accurate in recording these intangible cultural phenomena as he is in recording artifacts, and that the information he offers is reasonably accurate in many details. We must of course be exceedingly careful in the use of such ethno-linguistic information, since it remains unsupported. However, the fact that Herodotus provides us with information which can not be recovered by archaeological means, in addition to concrete details like those discussed above, makes his writings especially useful. Certainly, the work of Herodotus remains invaluable today.