At the turn of the last century, long before the Penn Museum began its work at Abydos under David O’Connor and William Kelly Simpson in the late 1960s, the site of Abydos in southern Egypt was the focus of intense archaeological exploration. At that time, the Penn Museum was keen to build its Egyptian collection, but it had not yet begun its own archaeological work in Egypt. In order to foster its collection, the Museum provided financial support for archaeological work through a variety of different endowments, such as the Egypt Exploration Fund (founded in 1882 in the United Kingdom); its American counterpart, the American Exploration Society; the Egyptian Research Account (founded by W. M. Flinders Petrie in 1894 with the purpose of training his students in fieldwork); and the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, which Petrie founded in 1905. Because of its financial support, the Penn Museum received a substantial share of the finds uncovered by Petrie and other excavators whose work at Abydos in the early 1900s yielded tremendous results. Of the roughly 3,000 artifacts from Abydos in our collection, almost 2,000 of them derive from these early excavations. The material consists of some extremely important, fascinating, and beautiful artifacts, of which only a small percentage are on display in our permanent Egyptian Galleries.

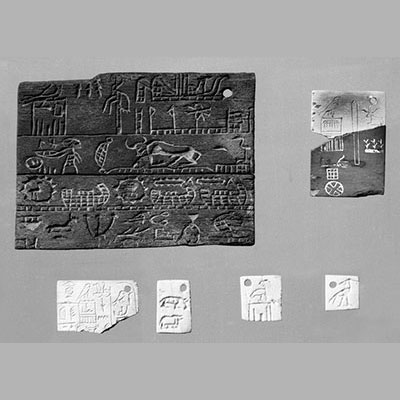

Arguably, the best known and most important of the early group of artifacts from Abydos to enter the Museum collection are those materials from excavations in and around the royal tombs of the kings of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties (ca. 3000–2675 BCE). These tombs are located in the area of Abydos known as Umm el Qa’ab, which translates as “Mother of the Pots” in Arabic, due to the tremendous quantity of offering vessels left on the surface by ancient visitors to the site. Flinders Petrie worked at the royal cemetery from 1900 to 1903 and some of the highlights of our first 8oor Egyptian Gallery—including 1 a calcite vessel with the name of King Narmer, 2 a funerary stela belonging to King Qa’a, and 3 small ivory and ebony tags bearing some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions from Egypt—come from these excavations.

These objects are important for understanding the formative decades of a united kingdom that would last for over 3,000 years. This material also demonstrates the early use of the hieroglyphic script. Many of the inscribed objects from the royal tombs bear a rectangular serekh, or palace façade, indicating the presence of a royal name 4 . Objects such as the gold-capped vessel 5 on display in the first 8oor Egyptian Gallery and the gold foil 6 used to decorate an object deposited in the Tomb of Khasekhemwy indicate the wealth of these early royal burials. Even incomplete objects 7 offer testimony to the skills of Egyptian artisans, and some of these objects provide insight into Egypt’s early interactions with its neighbors 8 . In addition to the burial of Egypt’s first named rulers, Umm el Qa’ab was the location of subsidiary graves of royal retainers whose burials surrounded the royal tombs. Petrie excavated dozens of these graves and the Penn Museum houses 27 Early Dynastic stelae, each decorated with the name of the deceased. Interestingly, two of our stelae marked the graves of individuals with dwarfism 9 .

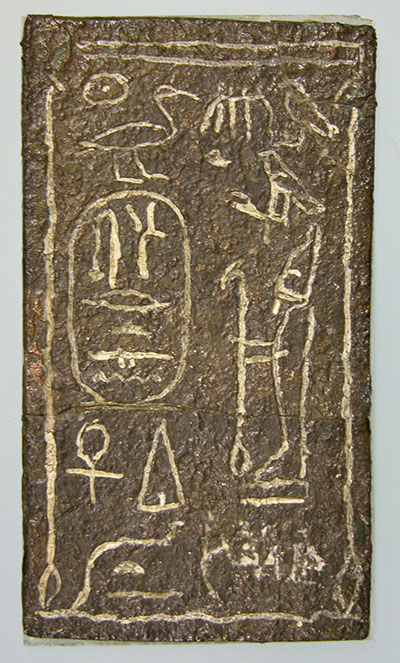

The royal cemetery at Umm el Qa’ab remained an important religious site well beyond the Early Dynastic period. Not only was this the location of the burials of Egypt’s early kings, it was also a site revered as the burial place of the god Osiris. Later pilgrims dedicated offering vessels and other types of votive objects at the site. One part of Umm el Qa’ab came to be called “Hekareshu Hill” by Petrie, as he found fantastically beautiful shabtis (funerary figures) and bronze model tools all inscribed with the name of a man named Hekareshu. Hekareshu’s tomb was not located at Abydos, but by placing objects bearing his name at the site, he could enjoy proximity to Osiris in the afterlife.The Penn Museum collection houses Hekareshu’s bronze model tools 10, some of which bear his name (shown to left of tools). Petrie’s work was not limited to the area of the royal tombs. He also excavated in the area of the Osiris Temple where he found foundation deposits, including this bronze plaque 11. Dating to the 12th Dynasty, this object indicates Middle Kingdom kings’ interest in the site. A similar type of dedicatory artifact, although from a much later date, is also in our collection. A contemporary of Petrie, Algernon Caulfeild, carried out excavations in the area of the Seti Temple in 1901–1902. Interestingly, in his publication of the site, he notes “I should like to have it thoroughly understood that I am not an Egyptologist; I am merely a rolling stone, who spent some months turning over sand and dragging a surveyor’s chain in the neighbourhood of Abydos. I do not guarantee the accuracy of my observations, or the accuracy of my drawings.” One of his finds, a small gilded limestone prism inscribed with a dedication text written in Greek is now in our collection 12. Given its 7nd spot near other inscribed material of the Ptolemaic period, scholars have dated this block to the reign of Ptolemy IV (ca. 222–204 BCE). This unassuming object gives indication that the temple pylon was rebuilt during the reign of this king and speaks to Ptolemaic interest in the site of Abydos.

In addition to the work carried out by Petrie, the Egyptian collection also benefitted greatly from John Garstang’s work at Abydos in the area of Arabeh (the name of a modern village at the site). Garstang trained with Petrie, and, in 1900, he excavated a cemetery site (Cemetery E) where he located graves dating from the Middle Kingdom through the New Kingdom (ca. 1980–1075 BCE). One of his remarkable finds was Tomb E108, a disturbed pit tomb that belonged to a man named Hor who bore the titles, Master of the secrets of the palace, Sealer of the King of Lower Egypt, and Overseer of sealers. In an area which tomb robbers had not accessed, Garstang found a rich set of Middle Kingdom jewelry including a girdle with electrum beads in the form of cowries, two ribbed bracelets of gold, a large electrum pendant in the shape of a shell, two small fishshaped gold and feldspar amulets, and a gold charm case 13. Two inscribed scarabs, including a lapis lazuli scarab set into a gold ring, and several strings of beads made of faience, garnet, and amethyst were also discovered, along with a statue of Hor (now on display in our first 8oor Egyptian Gallery). Jewelry of this kind is typically associated with women, which may indicate that a female family member originally shared this tomb.

Other striking finds from Garstang’s excavations include vessels made of brilliant turquoisecolored faience with black-painted decoration 14, decorative cosmetic containers 15 16, and bronze weapons with ivory handles 17.These finds span a number of periods in Egyptian history. Several uncommon items include an unusual bead (or seal) consisting of seven fused cylinders inscribed with the names of several kings of the 12th Dynasty 18 and a curious wax figurine (19, left, with three other examples from the British Museum). While the figure bears similarities to a shabti, it was originally one of a set of four figures (the other three are now lost) representing the four sons of Horus. In this case, the figure is Imsety, the god who typically has a human head, in contrast to the animal heads found on the other three gods. By the time of the 21st Dynasty, the use of canopic jars was waning.The internal organs were still removed and mummified; however, they were often placed back in the body. Wax images of the four Sons of Horus, who previously decorated the lids of the canopic jars, were wrapped with the internal organs to protect them.

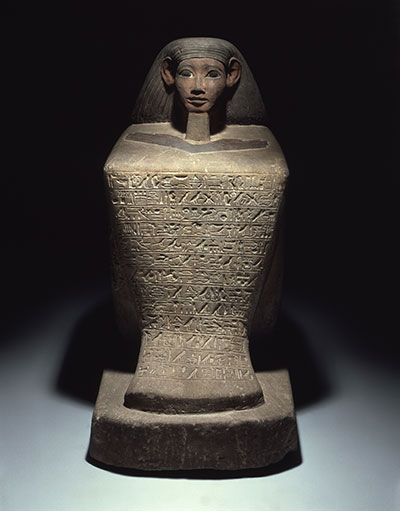

David Randall MacIver and another student of Petrie, Arthur C. Mace, also undertook excavations at Abydos from 1899–1901 in an area of the site termed “Cemetery D.” Here they uncovered graves dating from the Middle Kingdom through the end of the Late Period (ca. 1980–332 BCE). One of the most striking finds from these excavations is the block statue of Sitepehu, which is on display in our mummy room 20.They also found an unusual stela decorated with a cut-out ankh sign 21, which belonged to a man named Sobekhotep who held the title “Administrator of the Ruler’s Table.” His wife, Neferuptah, also appears on the stela.The burial was disturbed; excavators dated the stela to the 13th to the 17th Dynasties. From aThird Intermediate Period grave came an inscribed faience sweret-bead ornament 22, reading “The high priest of Amun, Pinedjem, son of Piyankh.”The man named is Pinedjem I— the high priest of Amun in Thebes who made the bold move of taking on the epithets and full titulary of pharaoh during the 21st Dynasty. In addition, the excavations also uncovered a group of shattered limestone statuary featuring traces of gilding and inlaid eyes 23.They were buried together and the excavators suggested they might represent materials from a sculptor’s studio dating to the 26th Dynasty. (664–525 BCE)

The objects illustrated here provide just a glimpse of the fascinating array of artifact types that come from early excavations in Abydos.The objects span the full range of ancient Egyptian history from the Predynastic through the Greco-Roman periods indicating the continued importance of Abydos to the ancient Egyptians.The material comes from both cemetery and temple contexts and re8ects both royal and non-royal traditions. Egyptologists around the world are very familiar with this Abydene material. However, visitors to the Penn Museum rarely get a chance to see these artifacts, which are some of the many hidden treasures housed in our Egyptian storage collection.

Jennifer Houser Wegner is Associate Curator in the Egyptian Section at the Penn Museum.

Key to objects

1. UPM object #E9510, Umm el Qa ‘ab Tomb B6/13, Dynasty 1, calcite, H. 26.9 cm

2. UPM object #E6878, Umm el Qa ‘ab Tomb Q, Dynasty 1, basalt, H. 1.43 m

3. From left, top then bottom, UPM object #E9396, E9403, E6880, E9395, E9393, E9394, Umm el Qa ‘ab, Early Dynastic Period, ivory and ebony

4. UPM object #E9556, E6881, E6862, Umm el Qa ‘ab, Dynasty 1-2, marble

5. UPM object #E9594, Tomb of Khasekhemwy, Dynasty 2, stone and gold

6. UPM object #E6883, Tomb of Khasekhemwy, Dynasty 2, gold

7. UPM object #E6865, Umm el Qa ‘ab Tombs U and T, inscribed fragment of rock crystal bowl (“Mafdet, Lady of the House of Life”)

8. UPM object #E9381, Umm el Qa ‘ab Tomb B17, Dynasty 1, ivory fragment with bound Libyan captive

9. From left, UPM object #E9184, E9933, E9499 belonging to Dedu, a dwarf, E9186, Umm el Qa ‘ab, Dynasty 1, limestone funerary stelae

10. UPM object #E9240 (yoke), E9241 (hoe), E9242 (adze), E9243-E-9244 (bags), Umm el Qa ‘ab “Hekareshu Hill,” Dynasty 18, bronze model implements

11. UPM object #E11528, Dynasty 12, bronze plaque found in bricks at Abydos Temple (white paint added in modern times) Egyptian Research Account (A. Caulfeild)

12. UPM object #E13376, reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator, limestone dedication block with gilding Egyptian Research Account (J. Garstang)

13. UPM object #E9190A-B (bracelets), E9195 (cowrie beads), E9198 (amulet case), E9193 (scarab), E9206 (hedgehog scarab), E9192 (ring), E9194 A-B (fish pendants), E9191 (pectoral), Dynasty 12, Tomb of Hor, electrum, gold, lapis lazuli, feldspar, glazed steatite

14. UPM object #E9207, Dynasty 12, Tomb E20, faience

15. UPM object #E9349 (kohl pot, Tomb E124), E9283 (kohl pot lid, Tomb 193), date unknown, faience

16. UPM object #E9282, Dynasty 18, limestone (blackened) kohl tube

17. UPM object #E9258, Late Middle Kingdom-Second Intermediate Period, Tomb E156, bronze dagger with ivory handle

18. UPM object #E9212, Dynasty 12, Tomb 282, glazed steatite bead/ seal

19. UPM object #E9248 (object on left), Tomb E256, date unknown, Tomb E256, wax visceral figure. Second image courtesy the British Museum Egypt Exploration Fund (D.R. MacIver and A.C. Mace)

20. UPM object #E9217, Dynasty 18 (reign of Hatshepsut), Tomb D9, sandstone statue with pigment

21. UPM object #E9952, Dynasty 13-17, Tomb D78, limestone stela with pigment

22. UPM object #E6766, Dynasty 21, Tomb 28, faience amulet

23. From left, UPM object #E9218, E9223, E9219, Dynasty 26, limestone statuary fragments with inlay and gilding