In 1957, the renowned archaeological illustrator, Piet de Jong (1887–1967), made his way to Gordion. Well known for his work at archaeological sites in Greece, particularly the Athenian Agora, he was invited by Rodney S. Young, Director of the Penn Museum’s excavations at Gordion, to prepare a series of drawings of artifacts and also to reconstruct the remarkable wall paintings that decorated the so-called Painted House. It was an extraordinary summer at the site, for the excavation of Tumulus MM, the so-called Midas Mound, the largest of the many tumuli that dot the landscape of Gordion, was commencing, and de Jong was to draw two of its most famous objects, the ram- and lion-headed bronze situlae while he was there.

Remembered as good company, a generous teacher, and a consummate storyteller, de Jong established a place for himself at Gordion, preparing object drawings and working with hundreds of plaster fragments that once formed the astonishing wall decoration of the Painted House (ca. 500 BCE). As he did at the Athenian Agora, de Jong made his reputation as an archaeological illustrator with his extraordinary watercolors of excavated objects, as well as with elaborate architectural reconstructions at sites in Greece, most notably the Palace of Minos at Knossos and the Palace of Nestor at Pylos. Trained as an architect, he brought a scientific clarity and architectural sensibility to his work that, when coupled with his artist’s eye, succeeded in portraying the true character of an object, as one sees in the fine series of pencil drawings of the miniature wooden animals from the child’s tomb, Tumulus P.

Some 35 watercolors of his reconstructions of figures in the processions that decorated the walls of the Painted House survive and form the bulk of his work at Gordion. These watercolors as well as his object drawings form the centerpiece of an exhibition, “His Golden Touch: The Gordion Drawings of Piet de Jong,” in the Museum’s Merle-Smith Gallery (September 26, 2009 through January 10, 2010). The exhibition is curated by Ann Blair Brownlee, Associate Curator in the Mediterranean Section and Alessandro Pezzati, the Museum’s Senior Archivist, with assistance from Peter Cobb and Colleen Kron, graduate students in Penn’s Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World program, and Gareth Darbyshire, the Gordion Archivist.

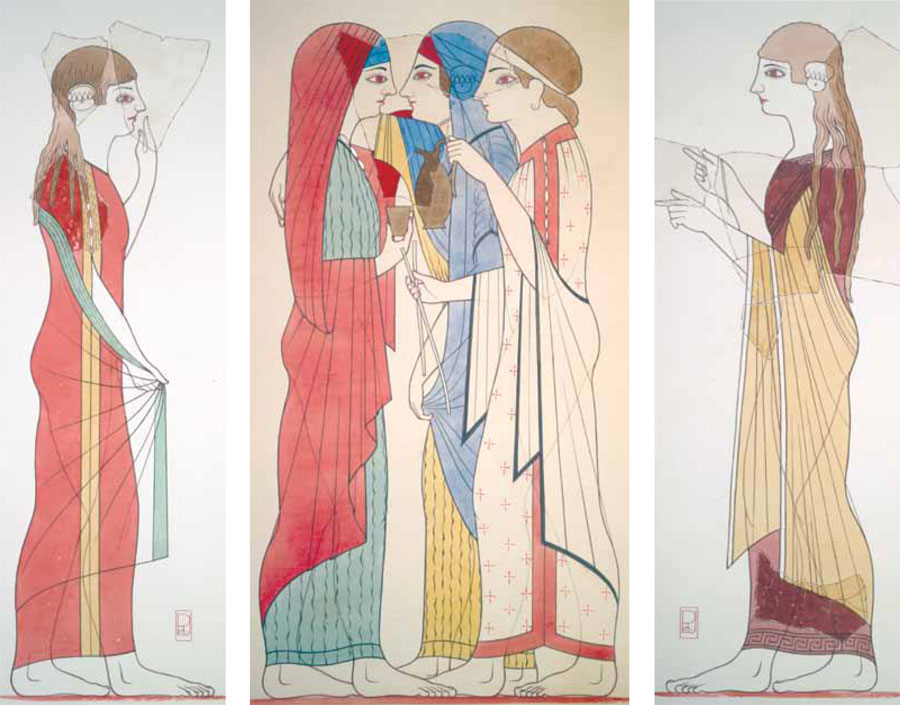

The watercolors show the many figures that must have made up the procession that decorated two sides of the Painted House’s main room and then probably converged on a third wall. Thousands of plaster fragments were recovered in the excavation and were painstakingly assembled into larger pieces, which de Jong incorporated in his reconstructions. There are a number of right-facing figures that form a long line, and they wear brightly colored clothing and often elaborate crowns and jewelry. De Jong reconstructed only a few left-facing figures, which must have decorated the opposite wall. He also did a number of heads of figures, which he was not always able to incorporate into the complete figures. There are also several watercolors that preserve lively multi-figure compositions. Most of the figures are women, although some men take part in the procession, and it has been suggested that the Painted House—actually a windowless partly subterranean structure—was a site of cult activity.

De Jong delineates the preserved plaster fragments in dark (or sometimes white) outline and in more intense colors; this makes clear how much of his reconstruction is conjectural. We learn something of his method from a series of preliminary pencil drawings on tracing paper that de Jong did as he attempted to position the many plaster fragments in their correct places in his reconstructions. They are full-scale drawings and are more than mere sketches. These drawings show grid marks as well as numerous corrections and notes and are a vivid evocation of the complicated process of drawing and reconstruction that precede the finished watercolors. Some of these preliminary drawings show the figures delineated in pencil on both sides. They demonstrate how de Jong transferred his preliminary drawing onto a sheet of paper in preparation for the final watercolor. He usually brought his own equipment and supplies, although in at least one instance, he acquired his paper locally, when he painted the glass bowl illustrated to the left.

Piet de Jong signed his drawings in several different ways, but the most distinctive is the version in which his initials or his full name are enclosed in a cartouche. The single-figure Painted House watercolors show the simpler version of the cartouche signature, while the multi-figure drawings show the more elaborate one, enclosing his full name. Simple and elegant, they recall his architectural side.

Piet de Jong has long been admired as an artist and archaeological illustrator, and his extraordinary drawings from Gordion, heretofore little known and studied, add much to our understanding of his work and his method.

- An extraordinarily fine pencil drawing of one of the miniature wooden animals from Tumulus P. De Jong sketched and did preliminary drawings in pencil, but finished pencil drawings are somewhat rare in his oeuvre. UPM Image #153694.

- De Jong did a number of watercolors of the heads of figures. This figure wears a crown with griffin heads. He would have used the more complete griffin heads from the headdress of another female figure to complete the griffins on this crown. UPM Image #153703.

- Several watercolors show more than one figure. The kneeling figure holds a pitcher and a drinking tube. UPM Image #153733.

- Three women stand in front of a seated figure, whom de Jong has shown as male. UPM Image #153734.

- Peter Cobb and Colleen Kron, graduate students in Penn’s Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World program, study Piet de Jong’s Gordion watercolors.

Hood, Rachel. Faces of Archaeology in Greece: Caricatures by Piet de Jong. Oxford: Leopard’s Head Press, 1998.

Mellink, Machteld J. “Archaic Wall Paintings from Gordion.” In From Athens to Gordion: The Papers of a Memorial Symposium for Rodney S. Young, ed. Keith DeVries, pp. 91–98. Philadelphia, PA: University Museum, 1980.

Papadopoulos, John K. The Art of Antiquity: Piet de Jong and the Athenian Agora. Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2007.

Digital Gordion: the Website of the Gordion Archaeological Project http://sites.museum.upenn.edu/gordion