A hallmark of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the strictly observed health code known as the Word of Wisdom, which prohibits the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, coffee, tea, and harmful drugs. Less known is that the Word of Wisdom has not always been as strictly adhered to as it is presently. In fact, most scholars of Latter-day Saint history acknowledge the evolving past of the health code from its implementation as a “principle with a promise” in 1833 to its current status as commandment and, thus, significant indicator of personal worthiness among Church members (Arrington 1993:250; Alexander 1979). My research with the glass from Block 49, the first Mormon pioneer cemetery in the Salt Lake Valley, provides insight into what was consumed by the first settlers and confirms the changing history of the Word of Wisdom.

On July 23, 1847, the First small company of Mormon immigrants entered the Salt Lake Valley and established a temporary camp. In the years following, thousands of Mormons flooded the valley, marking the beginnings of present-day Salt Lake City and other Utah settlements. Of particular interest to the Block 49 cemetery is the arrival of Charles C. Rich and company on October 2, 1847. Three days after their arrival, Rich’s mother, Nancy O’Neal Rich, died of pneumonia and exposure. Consequently, the following day, Rich proposed that a committee be created to select a burial ground for the city. It is believed that this proposal led to the selection of the Block 49 site for the cemetery.

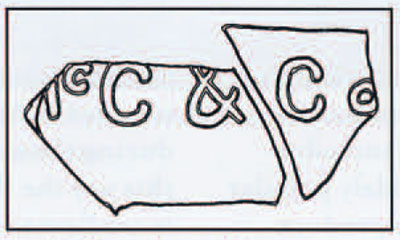

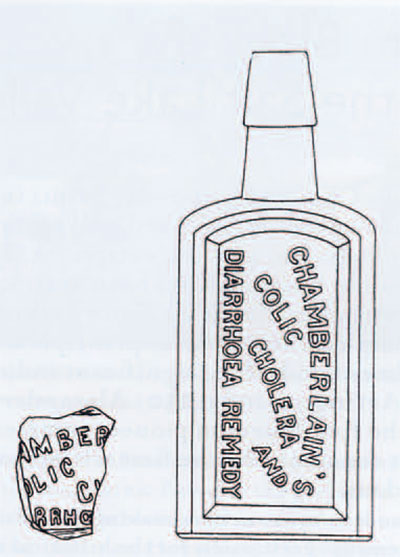

In 1986, Brigham Young University’s Office of Public Archaeology recovered a total of thirty-four skeletons at the site. Yet the extent of its use as a cemetery is somewhat unclear. Apparently the site was forgotten or deemed no longer necessary some time before 1870, when a Mormon-owned furniture factory was constructed on top of it. Most of the more than 1,600 pieces of glass excavated in the cemetery context are believed to date to this later period. Unfortunately, the context of the glass artifacts had been disturbed by historic plowing and modern construction, making their dating problematic. Fortunately for the historical archaeologist, however, a great deal of information can be gleaned from the artifacts themselves. In particular, embossed markings are useful in determining a bottle’s age, con¬tents, and manufacturer. For example, using collectors’ manuals and other research materials,the markings on the bottle fragments shown in Figure 1 reveal the manufacturer as William McCully & Company, Pittsburgh, PA, which produced bottles between 1841 and about 1886. Such markings can also help determine a bottle’s contents. The bottle fragment shown in Figure 2 originally contained “Chamberlain’s Colic, Cholera and Diarrhea Remedy,” made from around 1892 to 1930.

These and other embossed markings were crucial in dating the site’s glass artifacts. By averaging the dates of the various embossed fragments, an approximate manufacture date of 1885-1925 was obtained. Given this time span it is believed the glass artifacts are associated with the furniture factory rather than the burials. “Finish” or lip fragments from glass bottles are also useful in determining age and function. This is due to documented changes in manufacturing over time. Bottles exhibiting seams that stop in the middle of the neck or just below the finish are characteristic of bottles produced in some type of mold. Soon after their introduction in 1790 bottle molds became widely popular because they provided an easy way to produce relatively uniform bottle bodies in large quantities. This was a great advance from bottles that had to be individually blown. In contrast, seams that extend up both the neck and finish are characteristic of bottles manufactured in automatic bottle machines, invented in 1903 and still widely used today.

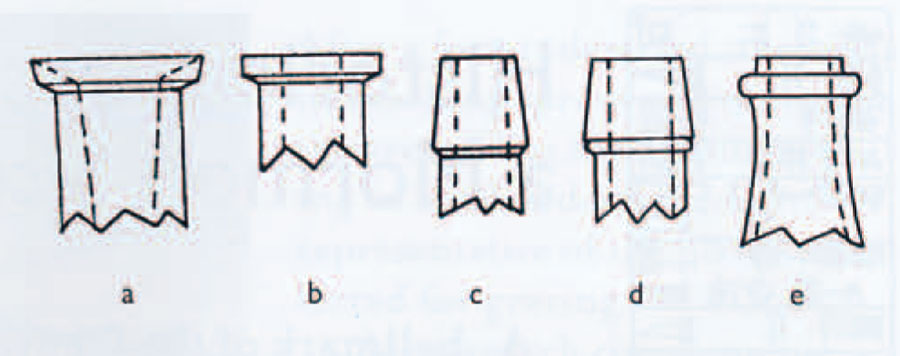

Analysis of the fragments found at the Block 49 site revealed that fewer than half were manufactured by automatic bottle machines. This means that most of those bottles whose finish fragments were preserved were manufactured some time between 1790 and 1903, a time frame that corresponds with the approximate date described above. Moreover, certain finish types are often characteristic of particular kinds of bottled products (Fig. 3). The significant number of “patent lip” and “prescription” finishes suggests a high consumption of proprietary drugs, commonly referred to as “patent medicines.” Also of interest is the recovery of two “champagne” finishes, along with a relatively high number of “oil” and “brandy” finishes, all of which are commonly associated with alcoholic beverages.

The glass remains of the Block 49 cemetery, therefore, suggest substantial alcohol consumption by the Mormons who worked at the site during the time the artifacts were deposited. In this way the fluid history of the Word of Wisdom is confirmed through archaeological analyses.

Benjamin Pykies

Ph.D. candidate, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania